For his first three years as a teacher in DC, Alejandro Diasgranados never had to wonder what to do for lunch. Every day at the ringing of the noon bell, he and his colleague Quay Dorsey would meet outside their classrooms at Aiton Elementary, descend the school’s muraled staircase, and head to Subway. Not that they liked the sub shop. In the food desert of the District’s Northeast corner, choices are limited. And no matter how often they’d promise to bring in something homemade, they’d show up instead with their bags full of lesson plans, running on the fumes of a few hours’ sleep, and share a look of understanding: Subway it is.

On the walk there, the teachers would swap updates on the complicated lives of their third- and fourth-graders, most of whom live in the nearby Lincoln Heights public-housing project. Eight-year-olds hit by drunk drivers, eight-year-olds who saw somebody set on fire last night, eight-year-olds surging up to grade level despite a recent placement in foster care or a cutoff of electricity at home.

On good days, they’d talk lesson planning, with Quay, 29, in the lead—he self-identifies as “bossy”—and Alejandro, 26, soaking it up like an eager younger brother. On tough days, they’d talk each other back from the edge. “One of us would be like, ‘I’m so done, I’m through with this,’ ” Alejandro says. “There’s times he kept me coming back to work, and same for me with him.”

They were two of the school’s most senior teachers— and only in their mid-twenties. But success came with personal sacrifice. Soon, one decided to quit.

An African-American and an Afro-Latino in a profession in which black men are a rarity, especially at the elementary level, Quay and Alejandro made an unusual duo. They wouldn’t even have been fast friends in grade school. Quay had played the lead in every musical. “I was one of those kids everyone knew and loved to hate,” he says. Alejandro had been a star football kicker who flashed golden cleats and went by the nickname Golden Toe Dro. But after Quay landed at Aiton, he heard about Golden Toe Dro through the Teach for America grapevine and helped get Alejandro hired. Over the next three years, they became known to every family in Lincoln Heights as the inseparable Mr. Dorsey and Mr. Dias. Together they created two of the highest-achieving classrooms in the school, spearheading an era of growth and hope in a building that has experienced some of the lowest lows of recent DC Public Schools history.

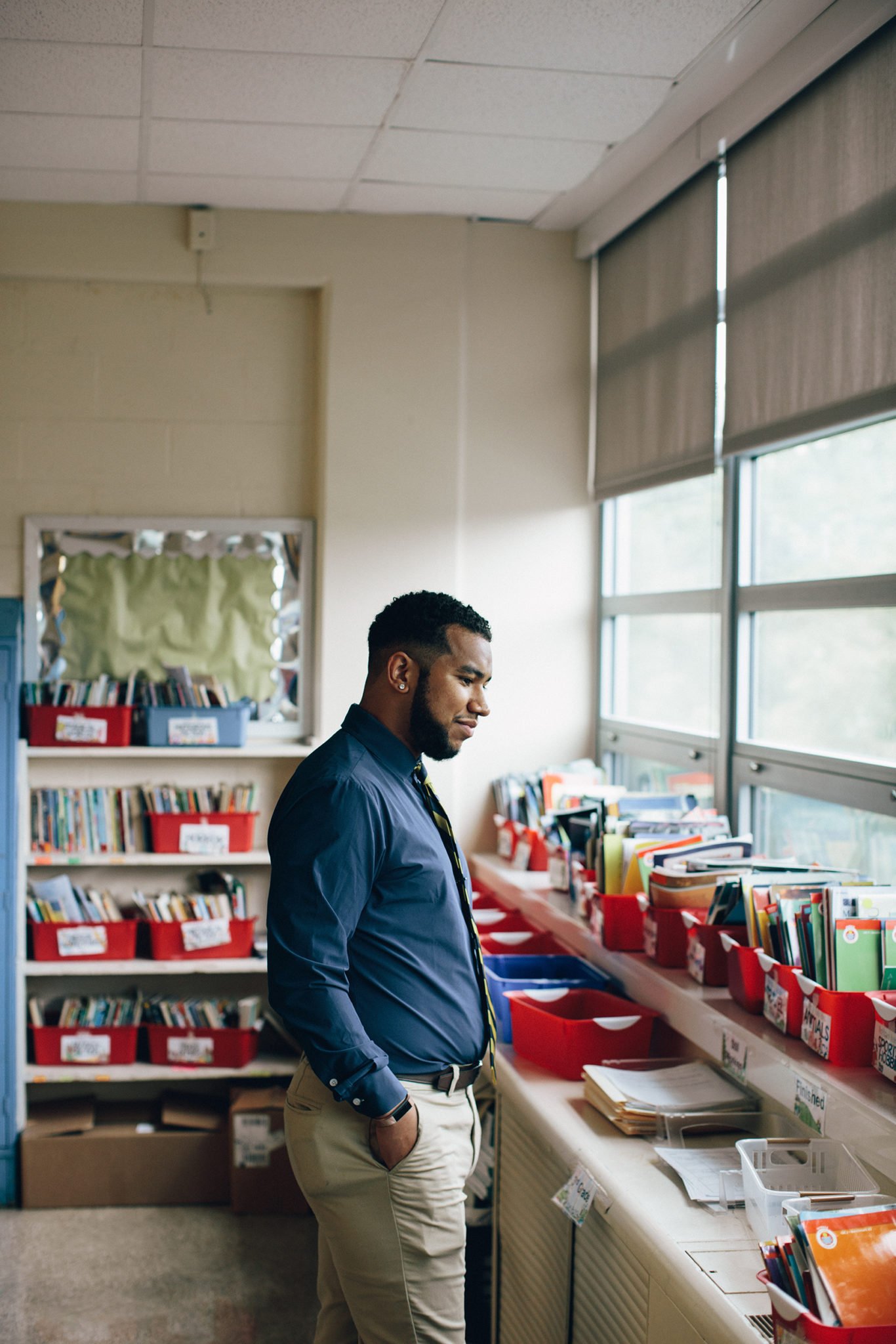

Alejandro Diasgranados. At 26, he's now Aiton Elementary's most senior teacher.

Alejandro Diasgranados. At 26, he's now Aiton Elementary's most senior teacher.  Quay Dorsey, a leader at the school and a beloved teacher, helped hire Alejandro. Quay found ways to connect with his students and deliver results, and became Alejandro's friend and mentor.

Quay Dorsey, a leader at the school and a beloved teacher, helped hire Alejandro. Quay found ways to connect with his students and deliver results, and became Alejandro's friend and mentor. Then last fall, Quay started talking about leaving Aiton, and this time he wasn’t just venting. The prospect, even in a school where teachers constantly churn in and out—no, especially in a school where teachers constantly churn in and out—was almost impossible for Alejandro to fathom. When he tried, it was overwhelming: If Quay left, he’d become the school’s senior teacher, at 26, an age that barely allowed him to rent a car and with only a few years of classroom experience.

So Alejandro broke the problem down into a more manageable unit: a $6.49 footlong. He thought about how for 30 minutes each afternoon—just enough time to buy a sandwich, wolf it down, and rush to the schoolyard for recess duty—he had a partner inside one of DC’s most needy and overlooked schools. Who would he go to Subway with now?

Around the time Quay was starting to think seriously about leaving Aiton, teachers at Ballou High School, a few miles down the Anacostia River, disclosed to WAMU that Ballou had been graduating students who didn’t meet attendance requirements. Soon after, an independent audit revealed the problem to be systemic, with teachers and administrators around the District pressured to choose between integrity and more impressive metrics. It was the first of a yearlong string of scandals that included a residency-fraud epidemic at the selective Duke Ellington School of the Arts and the departure of the school’s chancellor over charges that he’d improperly gotten his daughter a spot at another of the city’s top high schools.

Together, the fiascos have sullied DC Public Schools’ self-styled image as “the fastest-improving school district in the nation”—and forced a conversation about the conditions that gave rise to the moniker in the first place. Namely, a decade of education reform. A decade ago, 37-year-old Michelle Rhee became DC’s schools chancellor and, in the process, a national education celebrity. Rhee had a radical theory of change: Get rid of bad teachers, it went, and you’d raise test scores along with the fortunes of a city. At the time, byzantine union protections made it incredibly hard to fire a teacher, but Rhee essentially broke the union when she negotiated a new contract that enticed teachers to give up tenure in exchange for higher salaries. To be sure that the District retained only the best talent, she rolled out a system for grading teachers. Dubbed IMPACT, it tied those grades to standardized-test scores and in-class observations. Fail and you’re fired.

In Rhee’s three years in office, a quarter of the District’s teachers were replaced, along with a third of its principals. Test scores inched up. The approach was hailed as a success.

But it now seems clear there were unintended consequences. Ten years on, teachers have continued to depart at roughly the same high rate: About 20 percent leave the system yearly—significantly higher than in comparable urban districts. Because that figure doesn’t capture teachers who leave one school for another, the real magnitude of turnover is undoubtedly much greater. In other words, long after Rhee’s changes should have stabilized school staffs, the opposite is true. “We’re bleeding teachers,” as one employee at Anacostia High School puts it.

Some of this churn is a natural function of the talent pool the District began courting: highly educated twentysomethings straight out of college who might come to town for a few years but then move on for other jobs or opportunities. Rhee herself is a proud alumna of Teach for America, whose short teaching stints were modeled after those in the Peace Corps. Yet there’s a real worry that the District is driving away scores of good teachers who do see their job as their vocation—especially at the underserved schools that need these people most. Just look at Aiton Elementary.

It was a typical summer day in DC—“disgusting outside”—when Quay hurried toward Aiton for his job interview. He was 25, fresh out of Teach for America’s 2014 summer institute, and wanted to work at Aiton so badly that he’d blown off opportunities at other schools. He knew vacancies were constantly popping up, so it wasn’t surprising when he was hired on the spot in an interview that comprised only three questions.

For most DCPS applicants, Aiton tended to be a last choice. The school had burned through at least four principals in seven years and averaged a teacher-turnover rate of 44 percent, the highest in the city. People knew it as the locus of an infamous 2009 cheating scandal that had rocked the school district, in which answer sheets on a state test were found to have a suspiciously high number of erasures, a sign of doctoring by adults.

But Quay had interacted with Aiton students before, while working at a nonprofit that partnered with the school. There, he’d adopted a pedagogy of hands-on learning, an approach he’d seen work powerfully in schools like Aiton, where just about every kid is black, poor, and dependent on the school for life experiences that wealthier kids get elsewhere. Some Aiton teachers, Quay says, were receptive—“but there was a sense that you could only do that when you’re doing lessons in art, history, or science. They kept saying to me, ‘I can’t do this in testing subjects: reading and math.’ ” Having grown up in a poor neighborhood himself, Quay understood Lincoln Heights’ struggle: “I know what it’s like to have a mom who works your whole life but you’re still poor.” He felt convinced that once he joined Aiton’s staff full-time, he could do better.

“For the first month, there were probably 26 out of 30 nights I came home sobbing.”

As soon as he started, though, he saw what his predecessors meant. Hired to teach reading, he immediately found himself caught between the kids’ needs and his own need to align himself with the demands of the curriculum, which was influenced by the IMPACT rubric. Though he supported its standards in theory, the curriculum required him to teach on grade level, yet his students were typically reading several levels behind. “For the first month, there were probably 26 out of 30 nights I came home sobbing,” he remembers.

He took long walks in Rock Creek Park and tried confiding in everyone from friends to his grandmother, until he stopped confiding in anyone. He turned to his favorite books—from the weepy young-adult novel The Fault in Our Stars to The Lucifer Effect, about the Stanford Prison Experiment. He wrote poetry. “I just remember wanting the year to be over and hoping to be alive at the end.”

Though he liked Aiton’s then principal, he could barely get face time with her. She’d been brought in as a turnaround specialist and was working against the clock—research has found that it takes about five years to turn a school around, but new DCPS principals are rarely given that much time. By the end of the year, she was gone.

In the chaos of that first year, there was one good lesson Quay remembers. Protests were erupting after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Quay’s kids were noticing. Other Aiton teachers had advised him not to address the subject and to follow the curriculum instead. But one morning on a whim, he scrapped his lesson plan and picked up 40 copies of Express as he exited the Metro. He had his kids annotate the coverage (which met the curriculum guidelines), discuss the meaning of the words “privilege” and “justice,” and write their own news stories.

He’d never seen the students so excited to learn. “There was one boy who had been struggling before,” he says, “but his answer about justice was so sound and so unlike him that I was like, ‘I’ve failed you for most of the year because I didn’t know how to reach you.’ That’s when I realized this is what it’s going to take. It was so hard to get to that point, where I was satisfying the kids and satisfying the system at the same time.”

From there, the way forward became clearer. Rather than walking home trying to forget the day, he walked home remembering what had worked. He received a good grade on IMPACT and kept his job. Then it was summer, hiring season again, and in walked Golden Toe Dro.

At five-foot-eleven, Alejandro spent his first meeting with Quay looking up. Everything about Mr. Dorsey’s demeanor seemed to match his six-five frame. “He was very serious and professional, a natural leader,” Alejandro says. “He seemed like he’d been at Aiton for ten years. I thought, ‘Wow, this is what I aspire to be.’ ”

As a member of the interview committee, Quay was so struck by Alejandro’s affability that he made sure the Aiton administrators hired him then and there. Nevertheless, he tempered his expectations. “He’s green, for sure,” Quay thought. “People with his happy personality, they don’t stay long at Aiton.”

Alejandro had only recently stumbled into teaching. He’d attended public schools in Prince George’s County and made the Virginia State team as kicker—but NFL teams weren’t calling, so he went into physical therapy. When a peer in his mostly white certificate program shot a racial slur at him, Alejandro went to the administration and got no support. Livid and feeling lost, he walked out and started substitute-teaching for money. By the time he arrived at Aiton, he’d excelled in Teach for America’s summer institute. Still, he’d heard about the pressures of the IMPACT rubric. So he wondered: Would he be ready?

He wasn’t. Quay’s first-year struggles became Alejandro’s. He tried strategies he’d learned in Teach for America. He tried worksheets. He thought about quitting. Then he started to peek into the classroom next to his, where Quay was now teaching third-grade math.

“You could tell immediately that Mr. Dorsey had command of a classroom,” Alejandro remembers. “It was kind of like he was preaching a sermon to the students, or like he was in the middle of a concert.” Students gathered around different stations. Some would be measuring things and then acting those out; others would be on iPads drawing geometric shapes. In the middle of it all was Quay, pushing students at his desk to figure out new ways to solve a math problem. “There was not a lot of handholding in his teaching,” Alejandro says. “I’d never learned that third-graders could have such independent responsibility, and have pride in it, until I observed his classroom.”

Quay was the grade-level chair, a member of the academic-leadership team, and unofficial chairperson of all kinds of afterschool activities. Alejandro started to back him up. As he began to translate some of Quay’s ideas into his classroom, he worried that the older teacher might think he was a copycat: “I brought it up with him at one point. I said, ‘Am I stealing your work?’ He said, ‘This is teaching. We’re all in this together.’ ”

From then on, they kept nothing from each other. Alejandro began to bring his own ideas to Quay for validation. Should he have his kids read a novel about a teenager in prison? “That’s dope,” Quay would say. “Go do it.” (The students loved the book.)

The pair started hanging out after school along with two other young teachers. They called themselves the Bad Apples. “We’d text each other all day long, and it turned into critical conversations about culturally relevant pedagogy, school behavioral environment, everything,” Quay says. “Teaching can be very lonely, so we all kept each other in the classroom.” They made plans to start a podcast (working title: Bad Apples, of course). Then two in the group quit. Quay and Alejandro became the most stable presences in the school. By the 2017–18 school year, they’d been assigned to a combined third-and-fourth-grade class—Alejandro teaching English and Quay math.

By then, Alejandro had begun to figure out where his own instincts differed. Quay didn’t hesitate to get strict with students who misbehaved. He’d outline how they could write letters of apology, taking responsibility for their actions. That wasn’t going to work for Alejandro. “I tried to be intimidating, but whenever I yelled, my voice tended to crack,” he says. So when a student had an outburst, Alejandro would huddle up like a football coach, listen deeply, and, if necessary, play good cop/bad cop: “Mr. Dorsey is going to call home if you keep doing this.”

The teachers started to carry themselves differently when they walked around the neighborhood. They came to know which kids were parenting little brothers and sisters and which kids not to tell, “I’m gonna call your mom,” because their mothers were dead. They bought students clothing and brought families food. “Trust is the hardest thing to establish in a school with a high turnover rate,” Alejandro says. “Parents had been seeing new teachers come in every year, selling dreams to their child, and then they’re gone and the kids feel the absence, which is something they feel often in their own lives, with people just vanishing all the time.”

Under the leadership of a new principal, and with Quay and Alejandro leading the teachers, Aiton’s test scores gradually ticked up. Soon Aiton managed to outscore a couple of charter schools in the neighborhood, though it was still losing students to them. The new principal urged her staff to mirror Aiton’s upturn in their wardrobes, so Quay and Alejandro began to dress professionally alike: light-blue button-ups, ties, tan slacks. They walked in lockstep to Subway every lunch, gardened on the weekends to relieve stress, and woke up every Monday to do it all again.

For six weeks each year, Aiton administers the PARCC exam, a standardized test every DCPS student takes. (It stands for Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers.) The stakes are high: Staff jobs and bonuses depend on the scores. In the school, the mood shifts. Instruction and learning, in effect, peter out for nearly two months.

It was always a fraught period for Quay and Alejandro. Though they generally support the standards that the test assesses, the teachers couldn’t help but feel as if everything they’d worked for all year would unravel each spring. “We’d establish a strong environment with engaging lessons every day,” says Alejandro, “and that would just shut down during PARCC. Motivation becomes completely depleted. The culture of the school is gone.”

Some days, this futility seemed to crystallize in front of Quay, such as the afternoon last spring that drove him so crazy he chokes up describing it. He’d planned a lesson on percentages in which his students would calculate their basketball-shooting accuracy at little courts around his room, but when the kids came in from testing, they were “literally screaming about PARCC,” he says. “It was an explosion of frustration.” He abandoned the dribbling for a yoga exercise.

The stress, he knew, was something he’d pushed on them. For one thing, there was the personal pressure. Quay had been aiming for the top rating on IMPACT, which came with a $25,000 bonus—money that, when he’d gotten it in the past, had been instrumental in paying off student loans, financing a wedding, moving. But there was also the institutional pressure. Aiton is what DCPS terms a “priority school,” meaning it has a history of low test scores. Under federal law, priority schools are punished if scores don’t rise along predetermined levels—and principals’ jobs hang in the balance. In Quay and Alejandro’s experience, the message to Aiton from the central office was unequivocal: Raise the numbers or else.

“Parents saw new teachers come in every year, selling dreams, and then they’re gone.”

Stories abound of District teachers who lightly questioned the focus on numbers and were then admonished in front of other staff or received lower IMPACT grades. Quay and Alejandro liked the way their new principal ran Aiton, but even with a boss whose policies they supported, the pressure always loomed.

Now, after years of toiling over lessons that both hooked his students and served as test prep, Quay was starting to feel the effects. He’d gained weight. He never got enough sleep. Over four years, he’d spent about $6,000 of his own money on the classroom. Should he move on?

Thoughts of quitting came sporadically at first. “Something would happen and I’d get tunnel-visioned on the idea of getting out,” he says. “I wasn’t thinking clearly, and I wasn’t my best self.” But by spring he’d spun out the thought experiment and saw that there were indeed good reasons to leave. He wanted to go to a school without the Damoclean sword of the “priority” label. He wanted to focus on teaching, not test prep. He also wanted to move up, perhaps to an instructional coaching job, and he saw no clear way to do that at Aiton—he’d have to go to a school with more students and more community resources.

He interviewed for a position at an elementary school in the gentrifying Navy Yard neighborhood. It sounded dreamy: There was no priority label, he could coach other teachers in an official capacity, and the PTA provided money for classroom supplies. But he couldn’t help feeling he was betraying Aiton. “It’s hard to think I’m not this super-saver hero,” he says. “Over time, people who have cared well have moved on, in a community that needs people to stay.” He wondered: Was he an agent in all of this?

When Quay floated these thoughts on walks to Subway, Alejandro tried to be supportive. Quay deserved to grow, he told himself. And it would probably—definitely—be a while before he actually left.

But before Alejandro knew it, he and Quay were sitting together at Aiton’s annual spring meeting, where the staff fills out an Intent to Return form. Alejandro scribbled an affirmative on his, looked over at Quay’s, and saw that he’d circled “planning not to return.”

Quay watched his friend’s eyes widen. Despite the finality of the moment, he felt hopeful. “He won’t be able to say anymore, ‘Hey, Dorsey, how do I do this? Can you help with this?’ ” he thought as Alejandro stared back at him, shocked. “He’s now going to have to recognize that his own ideas are good.”

Alejandro has often asked himself: What could have kept Quay at Aiton?

Perhaps nothing. Quay was both burned out and restless to effect change at a level higher than the classroom—two quandaries that make it hard for many teachers to stay in one school very long. But when Quay breaks down his decision to leave, those aren’t the only factors. At Aiton, he says, he became a certain kind of teacher: no-nonsense, voice-raising, slightly severe. While that persona has always been seeded somewhere in him, he believes it emerged in response to the three-headed stress of trying to nail IMPACT, lead a staff under intense testing pressures, and somehow show his students that school could be applicable to their tangled lives. So many of the parameters that governed the working conditions within Aiton were things he couldn’t change and that were handed down by authorities outside the school, especially when it came to testing. Quay says he adjusted to those parameters so thoroughly that at times he no longer recognized himself—and that troubled him deeply. It was possible, he knew, to be a different kind of teacher, a more upbeat one. He just needed a different environment.

“He won’t be able to say anymore, ‘Hey, Dorsey, how do I do this? Can you help with this?’ He’s now going to have to recognize that his own ideas are good.”

Yet Quay did stick with Aiton for four years—longer than most colleagues, and long enough to mentor another teacher who can now take his place. One factor that kept him there was his first principal’s decision to elevate him to the school’s leadership team. Alejandro is now in the same position: He went to the current principal this past year wanting more responsibility, and she assented. He says that opportunity has kept him at Aiton, even as glitzier schools have tried to poach him. But if his principal leaves, as about 25 percent in the District do every year, he would have to negotiate his leadership role all over again.

When you talk to education gurus, you constantly hear how important it is for teachers—especially young ones in high-pressure urban districts—to band together and build relationships, both to learn from one another and to let off steam together. The difficulty, of course, is that networks like the Bad Apples can’t be legislated from above. An example: DC has encouraged teacher bonding through a professional-development program called LEAP, which sets aside time for weekly collaboration. But to many, it remains overly prescriptive and often falls flat. Better is the pair who, when the lunch bell rings, find themselves heading over to Subway.

So rather than dwell on what, if anything, might have kept Quay at Aiton, Alejandro has tried to look forward. He has spent time visiting his first-grade teacher, who two decades later still works at the same grade school in Prince George’s County and whose deep ties to the community he admires. He has asked groups of teachers at schools with lower turnover rates how they’ve stuck together so long.

“I’ve become aware of how important it is for teachers to have community,” he says. “That gets left out of a lot of teacher-turnover conversations. So I’m going to go into this next school year really trying to focus on that at Aiton. That’s hard to accomplish. But teaching is almost impossible to do alone.”

The end of the school year felt to Alejandro like watching President Obama’s last days in the White House. Mr. Dorsey’s farewell tour of Aiton culminated in an emotional speech at graduation for the fifth-graders, his first students. They’d had several teachers quit on them midyear, but Quay stuck with them. At the ceremony, he read a poem he’d jotted down on one of their first field trips, about how the students, though young, already possessed wisdom beyond what numbers and grades could reflect.

The next day, the students gathered around him, unusually somber, and he hugged them goodbye. He couldn’t bring himself to do the same to Alejandro—it would have been too emotional, and he didn’t really need to, as they texted each other all the time. So when the last bell rang, he just walked out. “There’s nothing to think about,” he tried to tell himself.

When Alejandro checked later that day, Quay’s classroom was locked and his name had been peeled off the door.

Over the next few weeks, Alejandro would feel everything. At staff meetings, questions came up about all the Aiton traditions Quay had spearheaded. Alejandro had to fight the urge to look over his shoulder. “Where’s Dorsey?” he caught himself thinking. “He should be answering this.” At times, he almost hoped Quay would call and say another job had magically opened at his new school. Or maybe not. He knew Aiton needed someone to fill all six-feet-five-inches of Quay’s absence. He just wasn’t sure he was there yet.

But then summer school started, and kindergartners started calling him Mr. Dorsey. These kids had never met Quay—at most, they’d heard about him from a sibling or a parent or another teacher. “I’d tell them, ‘For the 20th time, I’m not Mr. Dorsey,’ ” Alejandro says. “But to them, I probably looked like him—I’m a black teacher in a shirt and tie.”

The students would sometimes call him this as they sat in the cafeteria at the end of the day, goofing off and waiting to be dismissed. Alejandro briefed the new teachers on how important dismissal was to Aiton’s culture. Someone who isn’t invested in the school only silences his own students, he told them. A dedicated teacher cares about the whole cafeteria, as every student in there could someday be his. This is one small way, he explained, that a school transforms from a collection of itemized classrooms into an organism that breathes and grows.

Quay had always made the whole cafeteria his business. With one long arm raised in the air, he’d yell the school chant—“Aiton, Bears, Bears!”—with all the drama of a slam poet. The entire school would chant back and then immediately fall, eyes fixed, into a hush.

The first time Alejandro tried it, the kids looked at him funny. “Mr. Dias doesn’t usually yell,” he imagined them thinking. It was true—that wasn’t his style. So the next day, he did it his way. He walked in, silent, and put his hand up in the air, until every Aiton student stopped talking and turned toward him.

This article appears in the November 2018 issue of Washingtonian.