In the early 1960s, long before bluegrass was streamed into the living rooms of genteel NPR listeners or championed by retro-craving hipsters, the place to hear the best hillbilly music around was the District of Columbia, and the people to see were the Stonemans.

The band was five siblings, all in their twenties, loud and brash and full of sap. Scott was the eldest, and he played a fiddle soaked with his sweat. He’d swap his bow for a coat hanger, then a comb, then a pencil, then a toothpick, without missing a note. On upright bass was Jimmy, who slapped the strings so hard, his fingers were taped to keep them from bleeding. He had epilepsy, and during his periodic seizures, the band played on as he recovered off to the side. Baby brother Van sang, played guitar, and emceed.

But the big billing, the main attraction that drew patrons six nights a week to a rollicking joint called the Famous, was the guys’ sisters.

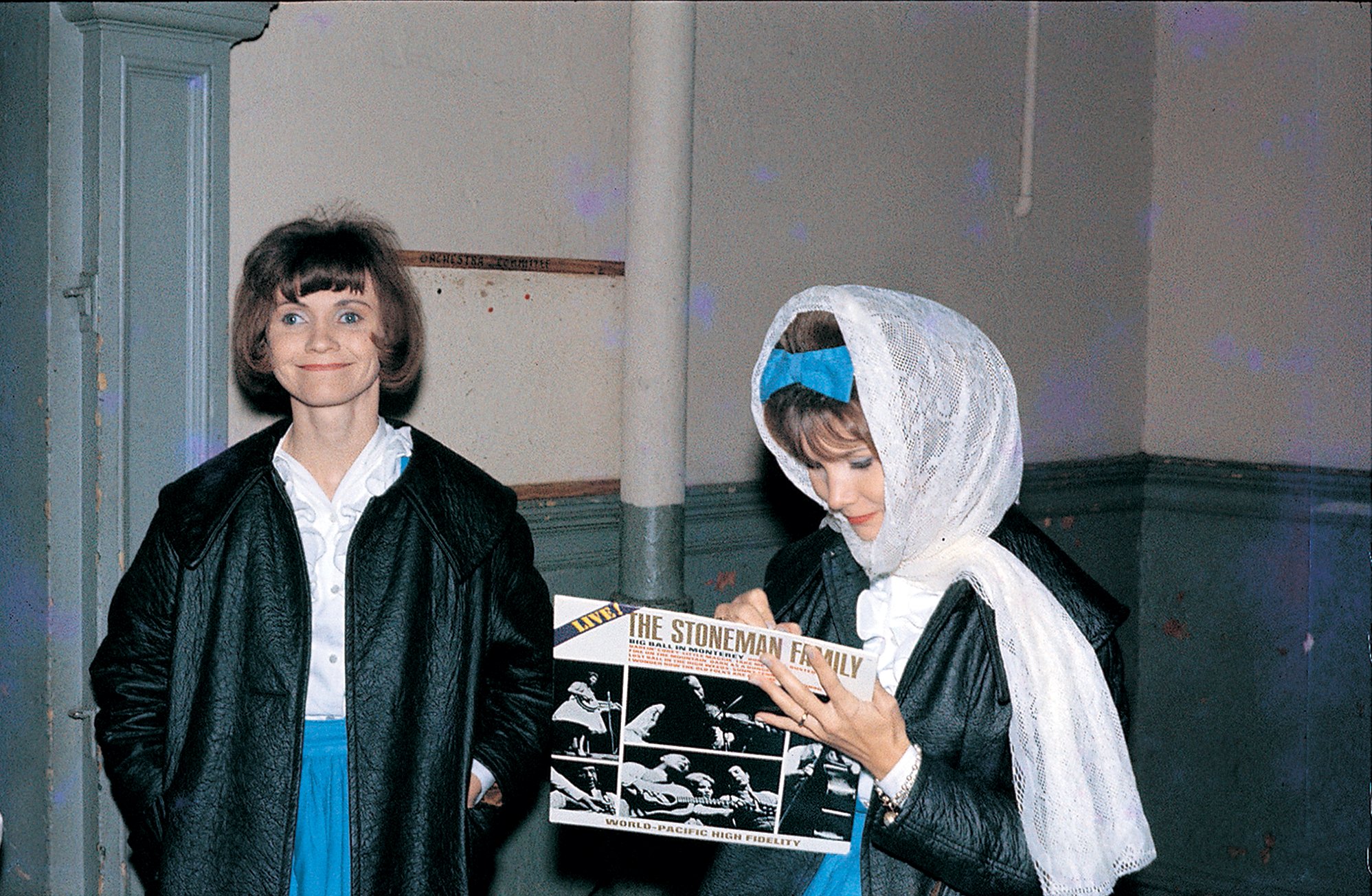

Donna was the Southern belle. A petite blond dynamo who danced a delirious jig while shredding jazzy solos on her mandolin, she picked the strings with her teeth and played behind her back. Her kid sister, Roni, was a tomboy who fired off mean banjo rolls in the machine-gun style of bluegrass demigod Earl Scruggs. Roni could toss off a wistful rendition of the Civil War folk tune “Home, Sweet Home,” then bait the audience, “I told you I was good,” before shouting down a catcaller with “If I kiss you, will you go away? Cool it, baby!”

Between them, the combustible Stoneman sisters generated enough heat to end the Cold War.

But just as remarkable was the fact that they were stars at all. Women had long been in the spotlight in country music, but mostly as singers or as stage dressing. bluegrass is a man’s music, the old bumper stickers used to say. For a pair of sisters to work the lead instruments in a genre dominated by good ol’ boys was radically new—a riot grrrl revolution, hillbilly-style.

“Donna had a sound all her own, and she never stopped moving. Roni was a good banjo player, but more than that, she was a great showman,” says Bill Emerson, cofounder of the legendary DC bluegrass band the Country Gentlemen. “They were exciting, and people loved ’em.”

Long before public radio championed bluegrass, DC’s Stoneman Family was the band to see.

Which makes it a little bit crazy that their pioneering influence on Washington has remained largely unsung. The conventional narrative about the region’s music folkways celebrates the ’70s and ’80s as the moment when DC became known as the Bluegrass Capital of the US thanks to refined, all-dude groups that preened on public radio and dished soft-rock covers to an affluent new fan base.

But it was the Stonemans, beating their brains out for chump change in downtown dives, who helped birth the scene in a town that, during their heyday, was full of displaced rural folk. Revving up songs as old as dirt, the sisters reigned over the honky-tonks that covered the map and filled the police blotter. They represented Washington on national TV, they stood up to music-biz bigwigs, and they fought rampant sexism, all without ever making it past eighth grade.

Now, a half century later, they’re the last members of the legendary Stoneman clan still alive to tell it like it was. Just don’t call them feminists.

“Bull hockey on that!” cries Roni Stoneman at the suggestion. “We were just minding our business, playing our music!”

Roni is still a spitfire, as salty at 80 as the feral banjo girl who fended off drunks at rough beer joints—“They used to call ’em skull orchards”—before leading her own all-female band years before the Dixie Chicks made it cool to be a chick playing country. Songs and sound effects pepper her mile-a-minute monologues dismissing contemporary country as “sissy” and modern bluegrass as “prissy.” Even the earnest young virtuosos at old-time festivals get a drubbing. “I don’t want to be hateful, but they’ve got it all wrong,” she says. “They don’t put any personality into the songs. They don’t have the feel for it.”

Her sister, Donna, is still the gracious and self-effacing one at 84. Ask about her dazzling dance moves and she credits the backbeat rhythm of Jimmy, who was so good, she says, that after a studio session with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul wanted to hire him. Inquire about her prowess on mandolin and she raves instead about Scott’s fiddling, tinged with jazz and blues and Western swing. “We didn’t go for that old draggy stuff,” she says. “We liked our music souped up. It came out of our soul—that’s the best way I can tell you.”

“We never heard, ‘you can’t do that, you’re a girl!'”

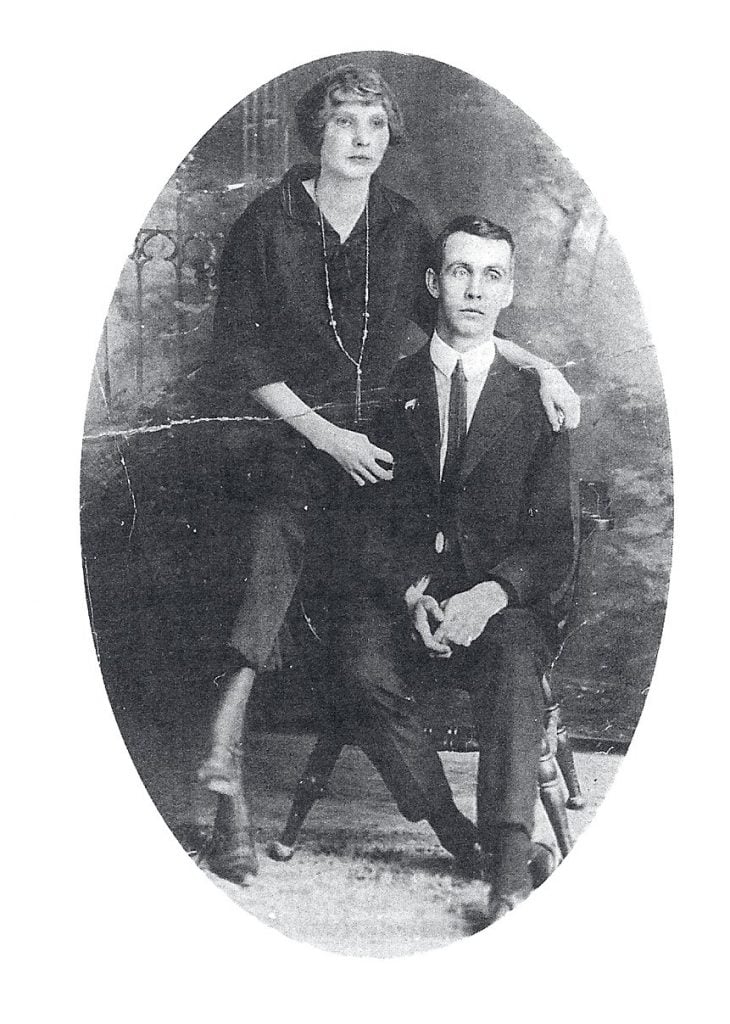

It came from kin, too. The sisters grew up in Carmody Hills in Prince George’s County, where their father, Ernest, and mother, Hattie, had fled from Appalachia. Ernest had been a country-music superstar, the first big hitmaker of the burgeoning “hillbilly” record industry, and Hattie had often accompanied him on fiddle. But the couple lost their fortune in the stock-market crash of 1929. So Ernest, a carpenter at the Navy Yard who helped do the wood-inlay finish work on FDR’s presidential yacht, used scrap lumber to stand up a one-room shack just outside the District line. Hattie, whose closet had once brimmed with silk and fur, sewed dresses out of flour sacks.

Even in an area teeming with dirt-poor migrants, the Stonemans stood out. “Little Donna, aged four, has dark circles around her violet eyes,” the Washington Times recounted in a 1938 story about the plight of the family—11 and counting at the time. “Scott, a mischievous imp of five with ash blond curls, dimples and an infectious smile, piped, ‘I’se dot bad tonsils, too!’ ”

Struggle as they did, the couple schooled their brood in their mountain roots and furnished them with fiddles hand-hewn from spare parts that “Pop” Stoneman scoured at junk shops. “Instead of toys,” Roni remembers, “we had instruments.”

As the self-described “runt of the litter,” Donna was drawn to the dainty-looking mandolin. Roni favored the banjo after her granddad told her a story about being a boy in the mountains of southwestern Virginia and falling for a girl with a banjo in a passing wagon train. What got him smitten wasn’t how she looked but how she played “Cumberland Gap.” “We never heard, ‘You can’t do that, you’re a girl!’ ” Roni says.

Eventually, music raised the family back up. Pop began moonlighting around town, while Scott mentored the next generation of bluegrassers, teaching them—and his kid sisters—the breakneck technique popularized by Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs. For Roni, that meant intricate, three-finger banjo rolls, a nonstop sheet of sound that delivered a signature propulsion.

“Scott showed me how the rolls keep the strings a-ringing,” she says. “He told us that just because we were girls, that didn’t mean we didn’t have ten good fingers and two strong arms and a good brain and the talent of a Stoneman. I learned how to mash the strings and practiced till my fingers were sore. I’d get so worn out, I’d run out to the woods and get on my knees and just cry and cry.”

In 1947, the family, including nine-year-old Roni and 13-year-old Donna, won a talent contest at DAR Constitution Hall, which earned them 27 weeks on a popular TV show hosted by DC promoter Connie B. Gay. None of the kids had ever seen an actual television before Pop took them to a hardware store for their first glimpse.

Still, the household of equal opportunities was something of a curiosity to the local musicians who flocked there. Roni recalls a visit from the Country Gentlemen’s Emerson, a bluegrass fanatic who had a car to make the trek from Bethesda. (His father owned a Buick dealership.) “Bill had his shiny new store-bought banjo, and I was picking on my homemade banjo, wearing my brother’s shoes and a little ol’ cotton dress my mama had made me,” she says. “I looked up and I said, ‘I can play banjo, too!’ And Bill told me I couldn’t play banjo, surely not in the three-finger style. I said, ‘What makes you say I can’t?’ And he said, ‘ ’Cause you’re a girl!’ ”

Roni walked over to Emerson and kicked him as hard as she could in the shin. Hattie, accustomed to sibling warfare, drew the line at lashing out at houseguests, especially one from Washington’s upper crust. She scolded Roni and whipped her with a hickory stick. Roni laughs it off today, but such incidents steeled her musical resolve, and by age 18 she’d made the first recording by a woman playing bluegrass-style banjo. “It was a time when women didn’t have much of a chance for a lot of things,” she says. “You just had to keep on a-trucking and not let it get to you.”

By 1956, the family’s band at the time, the Blue Grass Champs, had won every country-music contest around Washington, and one of their promoters wrangled them an audition on CBS’s Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts, the American Idol of its day. Godfrey, who had made his name on what’s now WTOP, was the most powerful man in broadcasting. He commuted in his private DC-3 between New York and his 1,970-acre estate near Leesburg. Auditions for his show were notoriously tough—among the many who tanked were Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley—and sure enough, Godfrey’s team was unimpressed with the Stonemans at first. But then producer Janette Davis pointed to Donna and said, “Let’s hear the girl sing one.” Donna sold Davis.

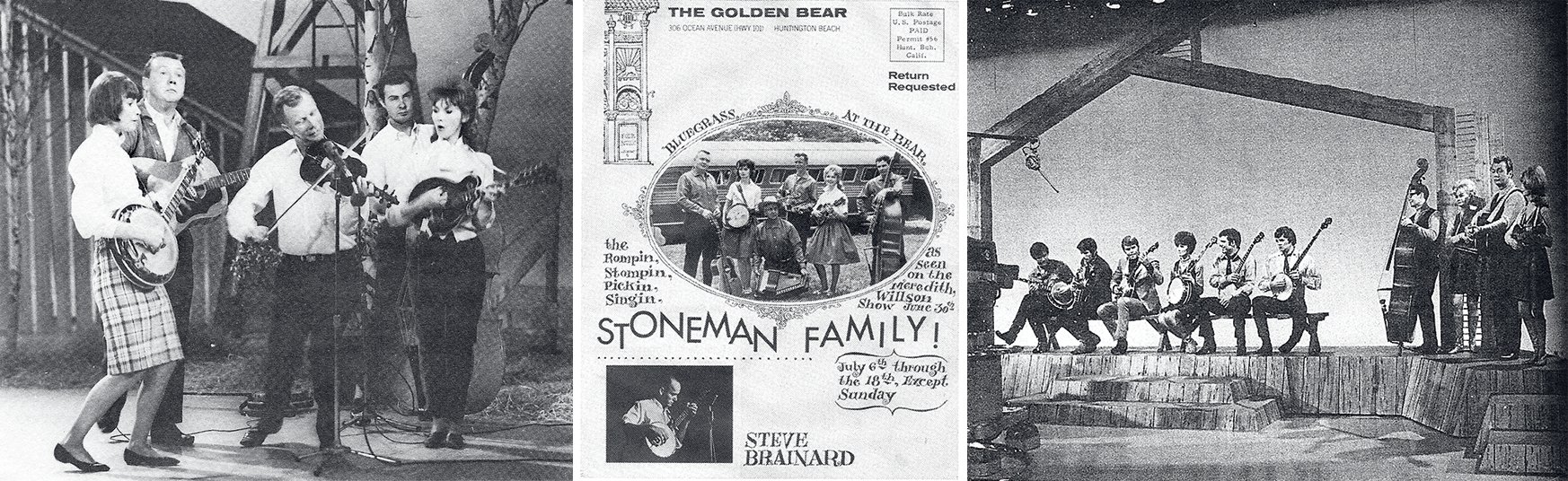

When the Champs competed on the show, dressed in blue gabardine country-and-western outfits, Donna held her mandolin up to the mike during the first instrumental break and coolly shredded a solo—thought to be the first time a woman sang and soloed on a bluegrass song on national TV.

The audience’s applause meter spiked. Yet all these years later, it’s the mishaps Donna remembers, such as when she muffed a vocal part or how she figured she and her “greenhorn” bandmates would never beat their competition, a pop vocalist from California. “We thought the girl singer was gonna get it,” she says. Then Godfrey announced the Champs. “It was my very first time wearing Western cowboy boots, and they were heavy,” Donna says. “When Mr. Godfrey called us onstage to shake our hands, I had the awfulest cramp in my leg and I almost fell flat on my face.”

The win earned the band a slate of guest spots on Godfrey’s other program, and he called Donna into his office to seal the deal. That was the first of too many times when she saw an ugly side of the business. Godfrey, a married father of three who was three decades her senior, asked her out on a date in his airplane, she says. She replied that she’d go, but only if her husband came along for the ride. “I shouldn’t tell this on him,” Donna says, “but I knew what he was after. So when I turned down his invitations, I figured I’d blew it.” Luckily, Godfrey held up his end of the deal and remained a staunch advocate for the band. (He died in 1983.)

The Champs’ lusty, unfiltered, mongrel sound—nowadays you might call them alt-country or Americana—cut a contrast with the era’s processed mainstream pop: 100-proof moonshine versus homogenized milk. One night, Donna was backstage when she overheard the famous McGuire Sisters gossiping about the Champs’ performance of the bluegrass chestnut “Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms.” Lay around the shack ’til the mail train comes back, roll in my sweet baby’s arms, the song goes—a little too suggestive for a pop trio who wore glitzy gowns and cooed like songbirds. “They were rich and glamorous,” Donna says. “We were poor and down-home.”

True, and in the rough-and-rowdy DC country-music scene at the time, that was gold.

Hundreds of honky-tonks catered to Washington’s postwar hillbilly stampede: the Ozarks, Pine Tavern, the Kit Mar, the Village Barn, Club Hillbilly, the Boondocks. The epicenter was the Famous Bar and Grill, at New York Avenue and 12th Street, Northwest, next to a bus depot. During the week, federal workers busted out of their boardinghouses and dropped by. On weekends, servicemen from nearby bases joined the scrum. What helped draw them in was a photo of Donna and the Champs in the window and the bar’s well-known slogan: every night is Saturday night at the famous.

The place was a dump. It had a few dozen tables, and near the stage was a five-gallon lard bucket with a hand-scrawled sign: ye olde pitch pot. “If you don’t pitch in the pot tonight, tomorrow night we won’t have a pot to pitch in,” Scott would say. The Stonemans needed the tips. It was six nights a week, five 45-minute shows a night, for $56 each.

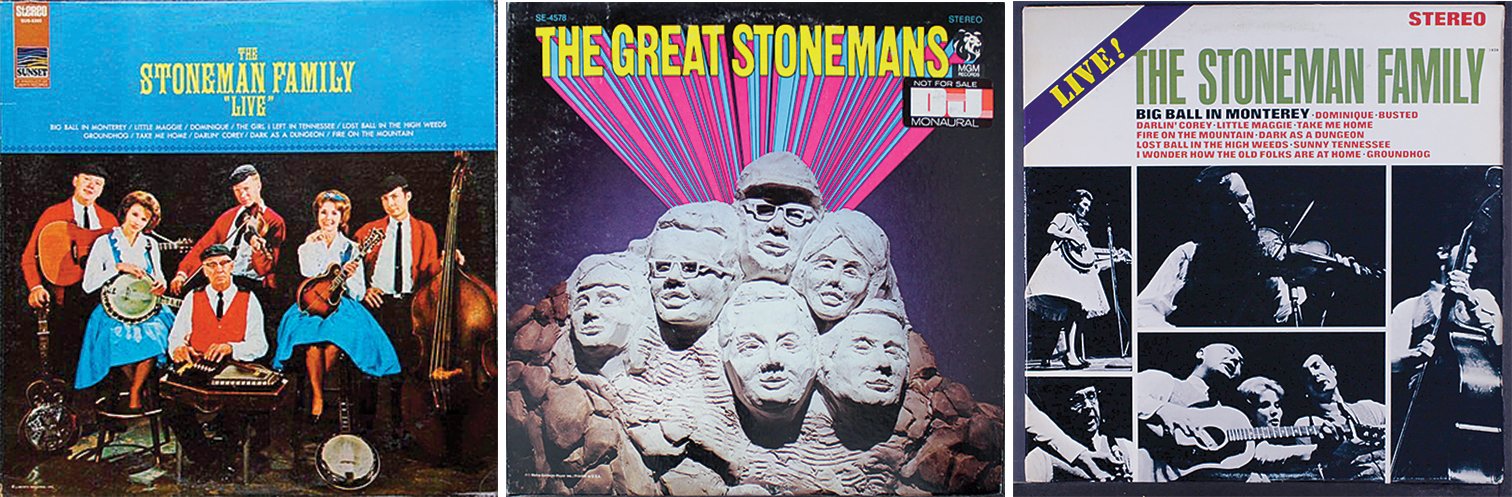

This was the fabled Stoneman family lineup of the ’60s—Scott, Jimmy, Van, Donna, and Roni—and the Famous was their finishing school, where they forged “one of the most sensational bluegrass bands of the modern period,” according to the definitive history, Country Music, U.S.A.

“They’d just take off like a daggone scalded dog and go out with a bang.”

“The Stonemans were the band,” recalls Margie Perkins Beaver, a Montgomery Blair High School grad who’s the widow of Luther Perkins, guitarist for Johnny Cash. Beaver and her best girlfriend both worked at the Pentagon and liked to catch the band whenever they could. “Everybody in town wanted to see them,” she says. “Donna was so darling, and Roni was so funny. They made a great team.”

One of Donna’s biggest crowd pleasers was her trick playing. She’d appropriate accoutrements of feminine domesticity, picking through a scarf covering her mandolin or donning garden gloves to bash out an old mountain tune like “Boil Them Cabbage Down.” Roni was the comedienne who billed herself as the First Lady of Banjo. She’d trade wisecracks with Scott and take over on Jimmy’s bass when his seizures hit.

“About halfway through a song, they’d get kinda excited and jump it forward about three or four beats,” says Bob Bean, the band’s manager. “And then at the end, they’d just take off like a daggone scalded dog and go out with a bang. It was something else.”

The sisters fed off each other’s energy and relied on one another for emotional support in the supercharged atmosphere that was their workplace. The men in the crowd ogled Donna. Certain male musicians weren’t gentlemen, either.

“During the intermission, you’d hear folks bragging on Donna and Roni, and that would really upset some of the old boys because they didn’t want to be bested by a female,” says Bean. “A lot of these guys got tired of hearing people rave about a pretty little girl bouncing around the stage and just playing the hell out of the mandolin. They were like, ‘Bullshit! How ’bout what I’m doin’ on my mandolin?’ ”

Sundays, the band worked outdoor venues, where urban folkie rivals displayed their own brand of sexism. Roni recalls a contest in Pennsylvania where she made it to the finals, competing against a folkie from New York. Roni was in sore need of the prize, a new Vega Earl Scruggs–model banjo. Backstage, the judges told her, “We can’t let a girl win. They’ll tear this place up.”

Fighting was so frequent that the sisters learned an escape route for every dive in town.

In that era’s bluegrass, this was no idle threat. Bottles and chairs went flying all the time. Fighting in a “bust-head” like the Famous was frequent enough that the sisters learned an escape route for every dive in town. Usually, the band tried to play through the ruckus. If it got too wild, they took refuge offstage, though Pop, a frequent guest, often stayed put and berated the “dad-blamed devils.”

One night, a regular at the Famous ran amok and the cops came. “The police took their billy clubs and knocked him on the head and kept hitting him, and blood was everywhere,” recalls Donna. “It was terrible.” Another regular was stabbed to death, and police showed Donna what was in his wallet: an autographed photo of her, clipped to a $50 bill. “I felt awful about it,” she says. “I felt like maybe I was the cause of how he got killed.”

Still, the Famous was always a second home, especially for Roni. One night when she was pregnant with her third child, the neighborhood prostitutes called her into the kitchen area before her shift and gave her a baby shower.

These days, the sisters live near Nashville. Donna has a coifed halo of cottony curls and bears a striking resemblance to her mother. Like her sister, she sprinkles her speech with snatches of singing and onomatopoeic renditions of their picking, a musical overflow as natural as breathing. For years, she was an evangelical minister, testifying to audiences around the world with a Jesus-loving sock puppet and her mandolin. Roni, with her smart bob and brash talk, could be the country cousin of Carol Burnett. Shortly before I spoke with her, she and Donna had done a benefit show for abused children in Nashville, and she joked to me, “How about a benefit for abused parents? I raised five children on my own.” Beginning at age 17, Roni was married half a dozen times. She says she finally made the right choice with number six, a Brit.

Inevitably, the conversation turns to the sisters’ old hometown. Back in the ’60s when the Stonemans toured the US, they championed their roots with posters proclaiming: direct from washington, d.c.

That affection has cooled in recent years, at least for Roni. “I ain’t gonna say I’m from Washington,” she half-shouts. “Not nowadays. I’m a Trumper! When people ask, ‘Where are you from? Where were you raised?,’ I tell ’em, ‘I was born in Washington in 1938, and that was just passing through with the family, finding work and playing our music.’ ”

“I ain’t gonna say I’m from Washington, I’m a Trumper!”

As success goes, she has a point. Despite their local fan base, a chart-topping record eluded the Stonemans in Washington. Their hyperkinetic energy did not translate well to the studio. Country, meanwhile, was going uptown—more Patsy Cline and polished crooning, less hayseed and hoedown. As adopted darlings of the folk boom, the siblings found gigs out west at Disneyland and on the California coffeehouse circuit, where they regaled young bluegrass devotees like Jerry Garcia.

By 1965, they had moved to Nashville, where they finally found fame. They toured with Johnny Cash (who injured Roni when he threw a stage prop while he was high on pills), they won the Country Music Association’s Vocal Group of the Year in 1967, and they scored their own prime-time TV show, Those Stonemans. They made movie cameos, most notably a wild scene in The Road to Nashville, with Donna shredding as Roni, on tambourine, shimmies beside her. (In a YouTube clip, one viewer raves: “punk as f—.”)

By the early ’70s, the sisters decided to pursue solo careers and other gigs. Donna’s marriage ended, and she took to painting for a while before being called to the church. She misses the unbridled joy of being onstage. “Sometimes I’ll be in a store with piped-in music and I’ll look around to see if anybody’s around,” she says, “and I’ll dance up and down that aisle, just trying out my steps again.”

It was Roni who became the most well-known Stoneman, thanks to her 19-year stint on Hee Haw. Remember the Ironing Board Lady? Roni’s harried Ida Lee Nagger was a trailer-trash caricature always sparring with her deadbeat husband. But Roni often chucked Ida’s rag-tied wig to pick the banjo with her fellow musician/actor David “Stringbean” Akeman, who would introduce her as “Roni Stoneman, my little friend from Women’s Lib.”

The sisters often struggled financially. Roni’s all-female country band, the Daisy Maes, was a short-lived venture, proving to her that audiences still weren’t ready for “girls who could play better than the guys.” Donna preached at prisons and small-town churches. “People would say, ‘Y’all are country-music royalty,’ ” recalls Roni. “I’d say, ‘Yeah, some royalty!’ ”

Meanwhile, back in the DC the Stonemans had left behind, a gentrified brand of bluegrass was flourishing in suburban venues like Bethesda’s Red Fox Inn. White-collar sophisticates clamored to see the Seldom Scene, with a surgeon on vocals. A group called Foggy Bottom featured members who worked at the Library of Congress and Goddard Space Flight Center. The formerly wild and woolly, Dickensian underworld of Washington bluegrass had become a million-dollar industry.

The sisters’ memories of home aren’t all sour. In fact, they’re a little sweeter these days, what with their old music once again catching the public’s ear. In July, a new CD of live recordings of the Stonemans from their heyday was released by the indie label Yep Roc. Hearing the band in its prime, putting its stamp on the frat-rock classic “Tequila,” you can understand why the CD promptly shot to number two on Billboard’s bluegrass charts. Whereas the treacly pop confections of the McGuire Sisters haven’t aged so well, the Stonemans’ heady brew sounds ready-made for Bonnaroo, fresher than ever.

If you go to Roni’s home, she’ll proudly play for you her father’s 1920s hit, “The Sinking of the Titanic,” on Edison wax cylinders, a format that predated records. (The Stonemans may be the only act in American music history to have their product issued in every format, from Edison cylinders to MP3.) She’ll also show you Donna’s painting of the Stoneman shack, long since demolished, in Carmody Hills.

“There’s such a big part of us there,” says Donna. “Whenever I go back to the Washington area, I think to myself how I miss it so much.” She says she now more fully appreciates her family’s rightful status in the storied music history of DC, which her father believed in when hardly anyone else did. She recalls with an almost embarrassed giggle that when Pop pulled up stakes to join them in Nashville back in the ’60s, he was disappointed with the meager price he got for the house he’d built himself.

“Even though it was just an old shack, Daddy felt it was worth a whole lot more. He said, ‘We should have got more money than that,’ ” says Donna. “After all, it belonged to the Stonemans!”

This article appears in the December 2018 issue of Washingtonian.