Nick Ryan has been walking around downtown DC for an hour after work, and it’s been, to put it bluntly, a bust. He has soldiered through Dupont to Foggy Bottom, down K Street to Farragut West, nose to the ground like a bloodhound heeding a bugle call, searching for a so-close-it-can-slip-through-your-fingers prize: the electric scooter.

By day, the 30-year-old works in business-to-business sales for Dun & Bradstreet, a good job with a comfortable salary of six figures. But at night, it’s all cargo shorts and sneakers, wild-goose chases and the thrill of the hunt. Ryan is the 21st-century, not-nearly-as-threatening version of a bounty hunter, though with less of a payout: He’s an electric-scooter charger. He hauls the dockless contraptions home to his apartment and plugs them in overnight—for $12, $15, sometimes $20 a pop. He’s nothing if not committed. So committed, in fact, that he’s mastered the art of riding two scooters at once so he can bring home multiples. “I don’t care what I look like,” he says. “I’m just looking out for myself.”

On this particular night, using the Skip electric-scooter app, Ryan has tracked five in need of human chargers, whom the company has self-importantly decreed “rangers.” (“Juicers” work for Lime and “Bird hunters” for Bird—don’t even think about getting those mixed up; people will correct you.) But each time the GPS brings him to a target, it’s MIA. There’s a glitch in the system, he says, and sometimes the map says a scooter is there, but a faster ranger has snagged it. Or sometimes it’s actually inside a building, where people have been known to hoard scooters, either for their own use or to wait for the bounty to increase.

It’s a bizarre concept, a part-time job that requires essentially no skills other than a little dexterity and a smartphone—bizarre, yes, but also pretty freaking amazing. “This is so easy, it’s ridiculous,” Ryan said a few days earlier on the phone. Why wouldn’t you do it?

Ryan got into the whole gig economy a few years ago while living in Atlanta. Uber had just gotten big, and as a traveling salesman, he figured it’d be easy to do after closing a deal or on the weekends. He doesn’t need the extra income per se—it’s more of, to use his words, an “I want to be able to burn cash” mentality.

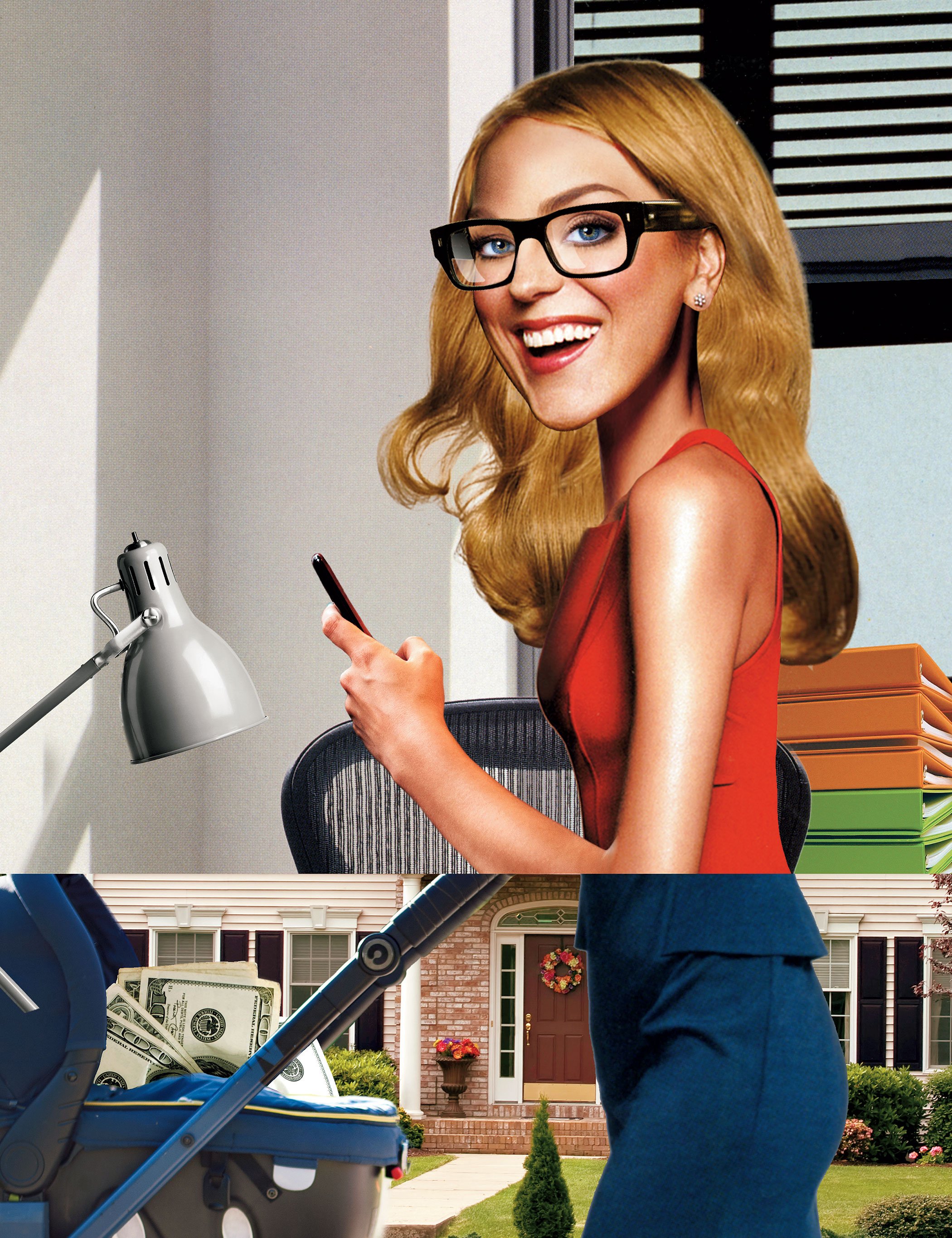

Trend watchers say we’re in the age of the side hustle—a feature of our redefined-by-the-recession economy. You tend to think of it, though, as a thing for cash-strapped millennials struggling to stay in the black amid scary student-loan debt and heart-stopping housing costs. You know—a stopgap for Generation Screwed.

That’s not an inaccurate picture of side hustlers in this city. Average rent for a one-bedroom in DC is $2,000 a month, according to Yardi Matrix, a commercial real-estate research firm. According to Lending Tree, the District has the highest median student-loan balance in the country, a byproduct of attracting overeducated young people who gravitate toward do-gooder but low-paying jobs. (The 2017 median income for a DC millennial was $63,000.)

But clicking for a payday from an app has also become a no-brainer for a swath of the 34-and-under set in Washington that you might not expect: all the Nick Ryans—young white-collar workers in search of extra money to blow on a night out in a city where the $14 cocktails rain down like confetti on the NASDAQ floor.

“The incredible weekend is pretty high on my list, and I’m willing to sacrifice a lot to do that,” says Ryan. “I went to Montreal for my bachelor party. Who the f— has international bachelor parties? Well, I wanted one.”

Like a lot of regional economists around the country, Ellen Harpel, founder of a consulting firm in Arlington called Business Development Advisors, has been looking at tax returns to see how people are plugging into the gig economy. She estimates that 10 to 15 percent of Washington’s workforce is doing gig work at any given time, meaning, in simplest terms, that they’re doing some kind of independent work in which they’re their own bosses.

But here’s the interesting part: While gig work has been growing here, our earnings from these jobs are lower than in other cities, and declining. What that suggests, Harpel says, is that Washingtonians aren’t turning to gig work out of economic necessity but rather to pad their take-home pay. “It really does seem like something that’s extra,” she says.

When gig work first surfaced, this isn’t how economists thought it would evolve. “What we know in 2018 is totally different than what we thought in 2016 or 2014,” says Caroline Bruckner, managing director of the Tax Policy Center at American University’s Kogod School of Business. “People don’t do this full-time. They do it typically as a supplemental source of income, and they cycle in and out. ”

People such as a 26-year-old woman who wanted to be identified by her middle name, Zoe. Before DC, she was in Nashville, where “I lived like a queen,” she says. “I had a master bedroom with an attached bathroom, a walk-in closet, two sinks, and a jet bathtub for like $800 bucks in a nice part of town. Then I get here and I’m like, $800 bucks gets you a shitty room in a dingy rowhouse.” After moving to Arlington, she became a barre instructor on the side. She pulls in $80,000 a year working in business development for a media company; clearly, she wasn’t struggling. But she lived next to the studio and went there all the time anyway—so why not get paid to work out? She’d teach a class three mornings a week and do a double-header every other Sunday. The gig paid $25 an hour, or an extra $250 a month after taxes. She’s actually on a hiatus from teaching at the moment, which means she’s had to cut back on the “bougie shit” that the job allowed her to buy.

“Like, I used to order Territory Foods all the time, and now I feel like I can’t do that,” she says. “That’s like $60 a week for food that’s not going to last me all week.” Which is to say that instead of shelling out for a few ready-made meals that are customized and clean (vegan, Paleo, Gwyneth Paltrow–certified, you name it), she now has to plate her own food.

Gen-Xers probably just finished reading that sentence and felt their eyes roll. They tended bar and tutored on the weekends so they could do adult things like pay off student loans and save for a house. (Now, Bruckner tells me, they’re mad users of Airbnb, trying to pay off said house.) When compared with that generation, millennials are often stereotyped as two-legged piles of burning cash, lusting for things like oat milk and beard oil. Maybe they could afford a mortgage if they stopped buying avocado toast, ha ha!

That’s not so wrong. In a 2017 study, Charles Schwab reported that six in ten millennials lacked a monthly savings goal or a household budget (eek), 70 percent admitted to buying clothes they didn’t need, and 60 percent spent more than $4 on coffee (hey, turmeric lattes don’t come cheap). As George Mason University’s Stephen Fuller, the Washington economist, puts it: “Self-denial is not in these days”—a slogan that’s probably screen-printed on a $90 piece of athleisure. “Long term is within the year, not within the lifetime,” he says, “and short term is this weekend.”

But maybe there’s another way to look at this, at millennials who think they’re comfortable even though they maybe live with seven roommates or in a studio with one window and who, at the same time, want extra money for kombucha or frosés. “While you’ve said they don’t need it, they probably do need it, because they think they need it,” Fuller says—they need to get out of that studio somehow.

And hey, the money is easy. Ten years ago, or not even, landing a side job usually meant showing up in person for an interview and providing references. Today you can download Rover from your windowless bedroom, pay $25 for a background check, and be qualified as a dog walker within a few days. “Your return on your investment is like, even if you only did it once or twice, if you want a little extra money—like, there it is,” says a 24-year-old District resident I’ll call Grace.

She walks dogs on Rover almost every day, along with her $47,000-a-year nine-to-five. (She declined to give her real name; while her employers know she walks dogs, they don’t know the extent of it—i.e., she sometimes does it on her lunch breaks.) For $15 she’ll take your four-legged pal for a 30-minute stroll, and for $40 she’ll keep him for the night. She says she makes up to an extra $1,000 a month on the app—her record is walking ten dogs in one day—which helps pay for all the kickboxing classes she wants as well as her $159-a-month Rent the Runway Unlimited membership.

“This is for me to go to a winery on Saturday and, like, ball out,” Grace says. “Like, if I didn’t have those [amenities], yeah, I’d definitely be fine. But I like the luxury, and I like to live the high life.”

Nationally, according to a JP Morgan Chase Institute study, more than 2 million households are taking in money every month through apps—or “platform work,” to use the lingua franca of economists. (No one who’s anyone seems to know precisely how many Washingtonians are doing it, but if you can tell me, I’ll walk your dogs for free.) The wages aren’t huge—JP Morgan’s study showed average monthly earnings of $828. Yet online gig work is the fastest-growing segment of the labor market, according to AU’s Bruckner, and is expected at least to double by 2020.

Set aside the depressing takeaways about our economy that finding conjures and it’s not hard to see the appeal for a young Washington resident who wants to finally eat fried quail at the Line hotel this weekend. You just click and pick up a job on a Tuesday morning or a Friday night or all day Sunday if you want. “It’s not as much responsibility as going into a separate place of work and having to be there for a night shift or something like that,” says Glenda Fu Smith, a 33-year-old nonprofit director who uses Rover.

If you’re like Smith, you can also basically double-dip. She works from home, boarding dogs in her Logan Circle apartment (for about $4,800 a year) while on the clock for her day job (which pays $80,000).

Kiersten Washle walked me through the genius of UrbanSitter, a babysitting app (whose workforce in DC is 71 percent millennials, btw): Instead of having to find and meet families and wait for them to hire you, sitters book as many appointments as they want—and the app shows where families are located, so you can pick a gig that isn’t three city miles away. Washle has become a super-user. On a weekend last year, she babysat Friday night after work, then had a Saturday-afternoon booking, followed by an evening one. She woke up Sunday to babysit at a church daycare, looked after another family that afternoon, then took a job Monday after work. That’s six gigs in 72 hours.

“This is for me to go to a winery on Saturday and, like, ball out.”

She’s 23, an engineer for M.C. Dean who has $70,000 in student loans that she’s determined to pay off by the time she’s 30. Although she says she’d be able to live comfortably on her salary, it wouldn’t allow her to have as aggressive a repayment schedule as she’d like. So she usually logs 15 to 30 hours of side hustles a week, at an average of $17 an hour.

“I feel like it’s pretty common to hear how much I babysit and be like, ‘Hold on, what? How are you doing that?’ To me, like, it’s just what you’ve got to do to get by,” she says. “I’m young and able-bodied, so I’m okay and can do it.”

Obviously, this kind of schedule can get in the way of life. Zoe, the barre instructor, says you can pretty much write off staying up late on weekends when you have to wake up the next morning to teach a roomful of chipper, Spandex-clad fitness freaks: “People aren’t showing up to be taught by some hung-over person.”

Therein lies a big paradox of the gig economy: Leaning in is so easy that leaning out becomes hard . . . even when you’d otherwise be balling out.

“I made $400 off a dog that was next to my house,” says Grace. She wasn’t planning on taking any more clients, but when she found out how close the owners lived, she couldn’t say no. “I mean, I’m a block away from my home, I can go home and cook, and I just have to let this dog out. I can use their laundry machine. I can use their shower. I don’t have to pay for any of that stuff.”

She thinks for a minute. “But then you’re like, oh, man—that Saturday night I wanted to go out, but now I have to go home.” Or rather, to someone else’s home—and let the dog out.

As Nick Ryan, the scooter charger, makes his way toward Metro Center, he passes the W Hotel, where he and his wife stayed once before they moved here. He talks about the rock star who had the room before them, who smoked so much weed that the hotel had to air the place out before letting them in. He describes his apartment at 14th and S in Northwest, the restaurants he’s tried—Estadio, Kinship, Bresca (he went before it got a Michelin star but found the skate wings too salty). He talks about the breweries he’d like to check out, the vineyards in Northern Virginia, the bars on U Street.

It’s your average conversation between two millennials on a walk, two child-free young people with steady jobs and a seemingly endless stream of weekends to fill with activities in Washington’s flusher-than-ever “pleasure-seeking economy.” Yes, that’s a Stephen Fuller Soundbite® again.

Unfortunately, Fuller also has a warning about the very gig work that has consumed the previous 284 lines. The forecast for the next few years’ local economy isn’t great, he says, and discretionary-type jobs are typically the first to go when times get tight.

Think about it—when you have to save money, you’re not going to call an Uber for a ride or pay a TaskRabbit to do your grocery shopping. “I think there’s a danger that we get dependent on all this extra income,” says Fuller, sighing. “We all begin to pull back, and the economy implodes to a degree because we’ve been built up on extras.”

Depressing, right? But all of that sounds so far away. So we might as well focus on the now for one minute more, that extra $12 parked around the corner, just waiting for Nick Ryan to pick it up. “We [millennials] have bitched and moaned about wanting to do things our way, and here’s a chance to do that,” Ryan told me. In his eyes, money is all about how you get it and how you spend it, not whether you do or don’t have it. (Shortly before this article was published, Ryan moved back to Atlanta and hit pause on his ranger gig.)

He never does track down a scooter. But maybe it was never really about the scooter. Maybe it was about the walk, and the decision to go on the walk and make some money. The thrill of the hunt in the dark of night.

“You can have anything you want,” he says before we part, “but you can’t have everything you want.” In other words, everything comes with a price, even if you’re setting one of your own. It’s a paradox that—as with so much of this story, as with so much of this moment in economic history and American culture—seems a little too ridiculous to be true but actually is: a notion I think about as I watch Ryan stroll along the crosswalk and into the evening, his head down as he stares at the app on his phone, waiting to catch the ghosts that flicker—just there!—then fade into the twilight.

This article appears in the February 2019 issue of Washingtonian.