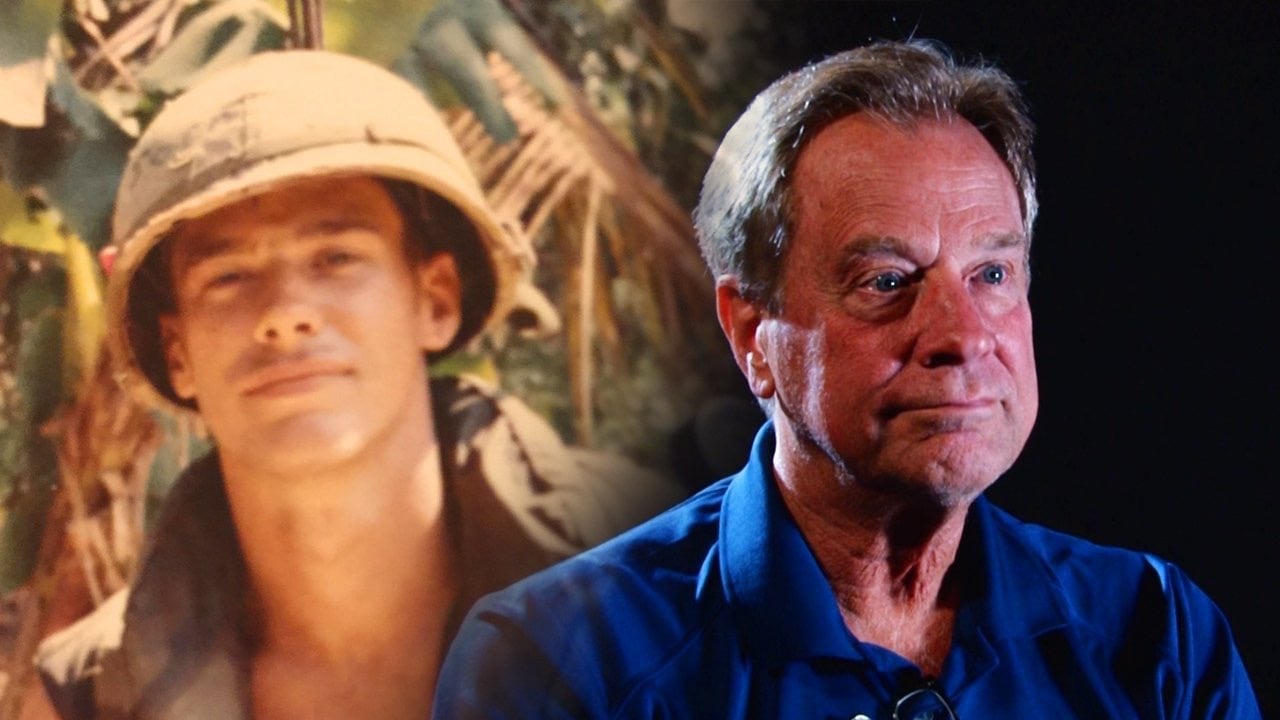

Bill Lord planned to write a humorous novel after he retired from local broadcasting, including 12 years as news director and station manager of WJLA, as well as two years in a similar role at WUSA. But in 2016, family members stumbled upon a cache of letters Lord wrote to his mother during the months he spent as a young draftee in Vietnam. They proved compelling enough that Lord decided to tweak his literary ambitions: The novel became a poignant memoir called 50 Years After Vietnam that deftly interweaves Lord’s present-day commentary with copy from his 1967 and 1968 letters.

In it, readers hear from two different versions of Bill Lord. There’s the 20-year-old kid trying to make sense of the mess he’s mired in, cautiously looking forward to a life of purpose. And there’s the retired newsroom boss, armed with experience and the benefit of hindsight, looking back on a life and career that were inexorably impacted by events that took place half a century ago, and half a world away.

Washingtonian spoke to Lord about the book, which is available now on Amazon.

The letters you wrote as a young soldier are remarkably well-written. What do you remember about your writing process back then?

There was no particular writing time or process. Obviously, we were on schedule for when we would be on the field for two, three, or four days on combat operations and then we would go back into the base camp or even stay on ships sometimes. We had two or three days off to recover from everything and that’s when I did most of my writing. But I did also write out in the field some of the time. I always kept paper and a pencil in my helmet, just in case.

You begin all the letters in the book with “Dear Mom,” which gives the impression that you and your mother had a close relationship. But that was not necessarily the case, right?

We didn’t get along very well. My mother was a great person, but she drank way too much and embarrassed me regularly and, you know, we just had a lot of different conflicts. She was a very, very difficult person. I may have said in the book that I never called her “Mom” outside the Vietnam letters. I called her Lucy, and it was not out of respect. But somehow, and this is one of the great accidents, she became kind of the lifeline for writing these letters.

Your early letters were upbeat, but especially after the Tet Offensive you began to criticize the war.

I was trying to be a good soldier, so to speak, but obviously you get beat down during the time you are in Vietnam. First of all, you realize that you have no business being there. You didn’t know until you got there just how stupid the war was and nobody could explain to us why we were fighting, and then along comes the Tet Offensive and it was a really harrowing time. You get rocked by those things. I would say in the immediate, post-Tet era, I was a little more scared and a little more willing to question everything.

You talk about how it can be good to be subversive. You write, “A true subversive undermines authority by simply doing the right thing without warning and then lets the bosses deal with it.” You went on to be the boss for a long time during your career. Did you encourage subversion within your newsroom staffs?

There are a couple of levels to that. First of all, I developed my subversive ways as a means of survival, and I found out that I was pretty good at it, and I did carry it into management. The one basic thing I would say is that I was a guy who always managed down and by that I mean I really took very seriously looking after the people who worked for me. I was very poor at managing up because I wasn’t a suck-up, I really just didn’t have it in me. I’m not sure if that had anything to do with Vietnam, but I just never wanted to kiss up to my bosses, so I was kind of a troublemaker, doing the things that they didn’t like a lot of the time. So there was that. And when you are in that position, you do find yourself sometimes having to kind of get people to go along with your way of doing things.

Your tenure at Channel 7 came to an end when Sinclair bought the station in 2014. Was your subversive philosophy something that didn’t match well their way of doing things?

The simple answer is yes. As it turns out, I met a lot of really nice people at Sinclair, but fundamentally the organization had a philosophy that I could not go along with and I was never going to be the kind of guy who could pretend to go along with it, so I essentially quit the day they got there. There was no anger. We just are fundamentally opposite in the way we do almost everything. It would have been a bad marriage. Again, I don’t have terrible feelings about Sinclair because they were fair to me, they were decent to me, and there are some really good people there, but philosophically, we were never going to be in the same camp.

How did surviving the pressures of Vietnam help you with many decisions you made as news director?

The primary thing is that a lot of people in the workplace get very stressed out in live television, when there’s breaking news and everything is going crazy. You have to be able to focus, to not be afraid, to work well under pressure, to make risky decisions. I guess I’ll give you one example and I’ll probably get in trouble for this, but we were in our afternoon editorial meeting at Channel 7 when this big earthquake hit eight years ago. We shared the newsroom at the time with Politico. When that earthquake struck, we stayed in our chairs until it stopped and then everybody on the TV side went immediately to get this on the air, get the weatherman up there, get news on the air and on the website. Meanwhile, everybody from Politico ran for the fucking door [Laughs]. They were standing outside the building, and we were doing television because we had a focus, we kept our heads about us. We knew the building wasn’t going to collapse on us, or at least we were reasonably certain that it wasn’t. A lot of people would have panicked and said, “Run for the hills,” but my instruction to them was, “Do your jobs, stay with it, get material on the air.”

Some of the Amazon reviews the book has received are from former employees who write about how much they liked the book but also how surprised they were to sort of learn about all the details of your life. Was Vietnam not something you talked much about?

I barely talked about Vietnam. It was something that I had set aside. And certainly, there weren’t many opportunities at work to talk about it. Generally speaking, people perceive you differently. Most of those people perceive me as the leader of their newsroom, and the authoritarian, and the person they have to work hard to impress. Meanwhile, I still think of myself as that 20-year old sitting around in rice paddies smoking dope.