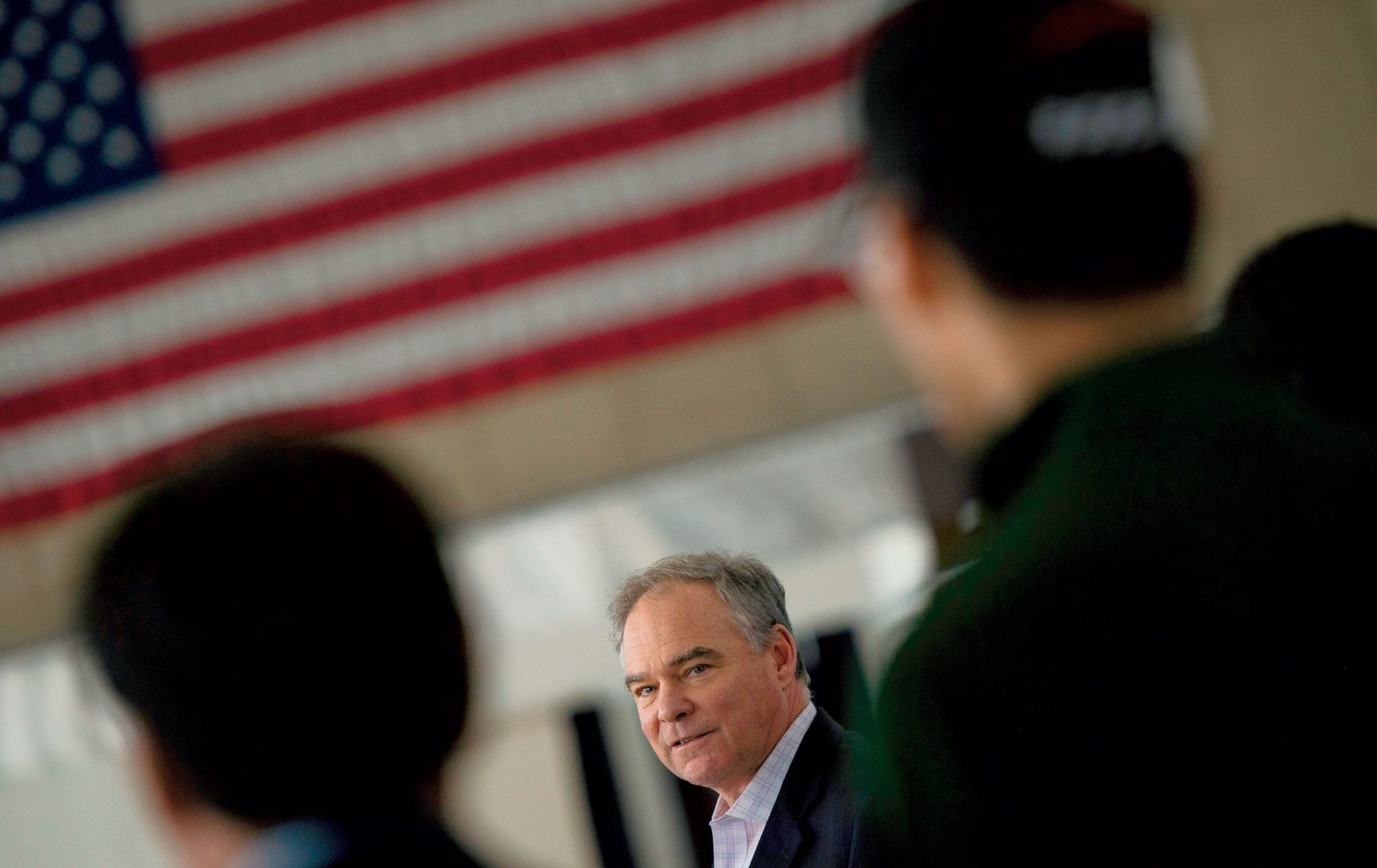

On the morning of the 2016 election, the Wall Street Journal published an interview with Tim Kaine about his plans for the vice-presidency—the kind of story you might read the week after an election victory. The genial Virginian spoke with uncharacteristic cockiness. Like Hamilton (the musical, not the man), Kaine said he’d be in the room where it happens “for every major decision.”

Within hours, Kaine went from plotting his tenure as the first Virginian since John Tyler to hold national office to cauterizing his wounds. The senator and former governor—who had done so much to turn the Commonwealth and especially the Washington suburbs blue—“was pretty bruised,” recalls Northern Virginia congressman Don Beyer, a friend of Kaine’s. As Senator Angus King, the Independent from Maine and perhaps Kaine’s best friend in the chamber, puts it, “It was a huge emotional blow.”

After the election, Kaine retreated to Richmond. Then went back to work, focusing on issues like health and defense even as the frenzied politics of the new presidency thrust other things into the headlines at breathtaking speed. He also declared that his presidential aspirations were behind him for the foreseeable future. He’d stay a man of the Senate. “When the campaign was over, I had the really strong feeling that, with being in the Senate, I’m doing exactly what I’m supposed to be doing,” he tells Washingtonian.

That decision has meant Kaine is now less visible, especially on the national stage, than a whole passel of formerly obscure Democrats who didn’t get nearly 66 million votes in the most recent national election. He hasn’t exactly gone underground: Kaine campaigned extensively to ensure his reelection in 2018, and he still does plenty of media interviews. But in general, his focus has been on Virginia, and he has chosen not to leverage his running-mate visibility for higher-profile airtime. When he does seek the spotlight—as when he prevented Senate adjournment during the shutdown mess—he says it’s primarily intended to help Virginia, and if it appeals to a national audience, that’s fine, too: “I don’t aspire to be a celebrity senator.”

That’s unusual. Most national nominees who lose start planning their comebacks quickly. But Kaine understands the political physics of the Democratic Party as well as he understands himself. There isn’t enough gravitational pull to get the 61-year-old into the 2020 presidential race, despite his profile and purple-state pedigree; six other Senate Democrats are already running, and they’re generally more left-leaning and diverse than Kaine. He’s also congenitally genial and bipartisan, which makes him liked in the Senate but perhaps a tougher sell in Trump-era Democratic presidential primaries. And Democrats frustrated by Clinton’s 2016 performance might not be keen to see her running mate jump into the heated effort to unseat Trump.

Plus, the forces keeping him in the Senate are powerful. Opportunities await: He could be majority leader someday, or Armed Services Committee chairman like former Virginia senator John Warner, whom Kaine cites as his Senate role model (sans the marriage to Elizabeth Taylor).

Kaine has chosen a path similar to that of another Armed Services chair, Barry Goldwater. Centrist-with-a-smile Kaine couldn’t be more different than the late senator, a crusty conservative who was crushed by Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 election. But after that, Goldwater stayed in the Senate for almost two more decades, retiring in 1987 when John McCain took his seat. Goldwater was a transformative chairman who passed landmark legislation stemming inter-service rivalries.

If Kaine were to attain that powerful perch, he could use it to promote his passion project: restoring Congress’s authority to prevent presidents from unilaterally launching military misadventures, an effort that has put him in conflict not only with the Trump administration but with President Obama.

At one point during our conversation, I asked Kaine if he thought his profile has perhaps become too low. He responded by noting that he has a gazillion Twitter followers he didn’t have before 2016, that he still does the Sunday talk shows, and that he has sponsored or cosponsored many bills under Trump. Kaine also crushed his Confederate-boosting rival, Corey Stewart, in the 2018 Senate race, winning by 16 points and helping flip all those congressional districts in the Commonwealth.

The ironic thing for Kaine is that just as he renews his focus on Virginia, the Democratic Party he helped build there has been imperiled by the madness in Richmond. His pleas for his friend Ralph Northam and Justin Fairfax to step aside have been ignored, just when the party is trying to capture a legislative majority this fall.

After the loathsome photo from Northam’s medical-school yearbook emerged, Twitter had a laugh about Kaine’s own shocking yearbook scandal: A photo made the rounds showing him sitting innocently on some steps in a ’70s-era rugby shirt with other University of Missouri students. The cherubic group turned out to be a club he helped lead to—yes, really—promote cross-campus friendships. It’s a nostalgic snapshot, but also telling: Nice-guy Kaine is probably correct that his talents are better suited to Senate consensus-building than to 2020 presidential-race trench warfare.

This article appears in the April 2019 issue of Washingtonian.