When journalist Amanda Kolson Hurley was growing up in Alexandria, she went on day trips with her political-science-professor dad. He was interested in urban history, and they liked to explore “places that functioned as suburbs,” she recalls, “but were really different because of the values behind them.”

Years later, those experiences helped guide Hurley toward a career covering urban planning, and when she was looking for a subject for her first book, she thought back to those trips. The result is Radical Suburbs, which looks at six bedroom communities around the country that have, for various reasons, defied stereotypes about the burbs.

One of the places she digs into is Greenbelt, created by the federal government as a cooperative community in 1935 to ease Depression-era urban crowding. To learn more about its history, I made the trip out to the last stop on the Green Line one afternoon to meet the author for a tour.

After we connected at a plaza in the middle of the historic town center, Hurley described how controversial Greenbelt’s founding was, given the whiff of socialism associated with a government-funded collective city. Hurley guided me up a winding path toward a series of low-slung, modernist apartment buildings. What looked to me like any other suburban complex was, she said, considered experimental and exciting when it opened, thanks to Art Deco and Bauhaus-like touches. The idea was to “make an architectural statement that they were looking forward to the future,” she said.

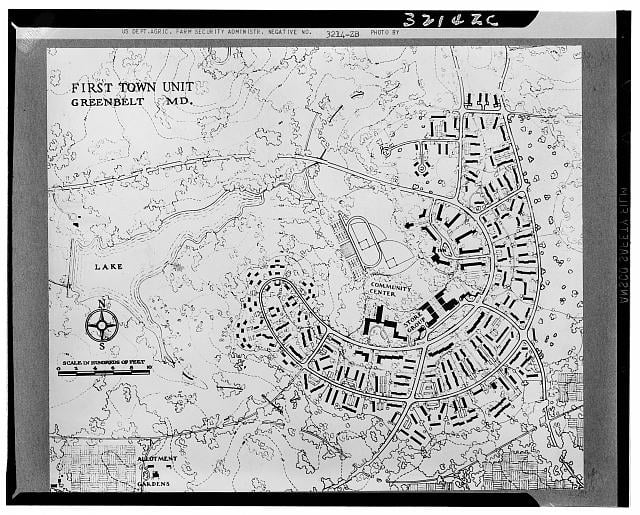

A map of Greenbelt's first town unit, 1936. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.

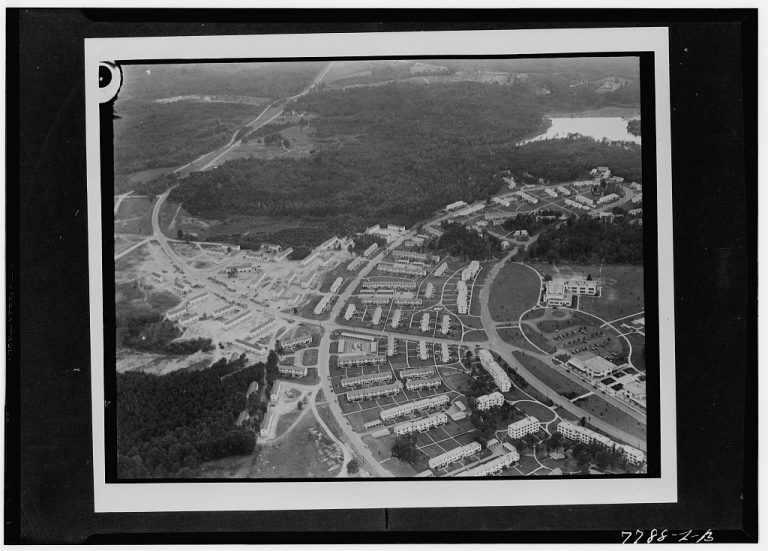

A map of Greenbelt's first town unit, 1936. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress. Greenbelt in 1941. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.

Greenbelt in 1941. Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress.Greenbelt is full of cool innovations, if you’re with someone who knows where to look. Hurley pointed out rowhouse clusters that face inward toward communal green spaces rather than having a traditional front door opening onto the street. And while the network of pedestrian pathways and underpasses might not seem notable now, in the 1930s they were unusual. But the most radical idea was the notion that the government could provide affordable housing that people would actually want to live in.

We finished the tour back in the plaza, in front of a huge Art Deco statue of a mother holding her child. “Decades ago, we were possibly further ahead than where we are now,” Hurley said as I gazed around the same suburban streetscape with a new understanding of what I was seeing. “Maybe we can use some of those lessons again.”

This article appears in the April 2019 issue of Washingtonian.