When Stephen Moret got his first look at the heat map, he feared the whole effort might be doomed.

It was September 2017, just days after Amazon unveiled its HQ2 contest, the nationwide race for a second corporate headquarters, and Moret, the top economic-development official in Virginia, had been scrambling to assemble the Commonwealth’s bid. As an initial step, he’d assigned a team of McKinsey & Co. consultants to analyze Northern Virginia’s chances of winning based on Amazon’s wish list for its new home: a talented workforce, accessible transportation options, high quality of life, and a favorable business climate. Using data from 20 distinct categories, the consultants had measured Northern Virginia against cities they considered top contenders and charted each location’s positives (in green) and negatives (in red) on the heat map for Moret.

Although Washington was alive with green for its many favorable data points, such as its diverse population and dense public-transit networks, other crucial variables were blocked out in red. The median rent, for example, was the highest of any site on the heat map, and labor costs were exorbitant. If Amazon opted for a less expensive metropolitan area, such as Atlanta, by Moret’s estimate it could save a billion dollars a year in workforce costs alone. On top of that, Virginia’s conservative approach to public incentives would preclude him from offering the generous deal sweeteners that other states could provide. “If they make this decision on costs or on incentives,” Moret thought, “we’re dead.”

From the outside looking in, there was every reason to believe that those considerations would play a pivotal role in Amazon’s decisions. The conventional wisdom about the modern knowledge-based economy, as popularized by Thomas L. Friedman’s The World Is Flat, has held that tech workers can do their jobs from anywhere. Companies can slash expenses and drive new profits, the thinking goes, simply by moving from big cities like San Francisco to mid-tier markets like Louisville or Wichita. To entice HQ2 to Washington, Moret would have to find a different playbook.

For the next six weeks, he worked with state officials, local politicians, and business leaders to craft Crystal City’s bid. Then, over the following year, he hosted site visits and coordinated discussions with Amazon executives entirely in secret, as the country waited in suspense.

You know the broad outlines of what happened next: On November 13, 2018, Amazon announced it had selected Northern Virginia and, in a since-abandoned arrangement, New York City—two of the most expensive regions in contention.

Critics immediately fumed that the contest was rigged, that Amazon had political motivations for wanting a bigger Washington-area footprint. It’s a charge that’s hard to deny. But even so, there’s another explanation for how the company selected these two pricey locales over hundreds of lower-cost options. It revolves around a set of ideas developed by a West Coast economist named Enrico Moretti—ideas that directly challenge the old world-is-flat consensus.

The jobs of tomorrow, Moretti’s research shows, aren’t heading to affordable markets offering lucrative public subsidies. They’re going to thrumming, dynamic cities that are already home to dense concentrations of highly educated workers. There are only a few of them, but these regions, the economist argues, offer employers such as Amazon advantages even more valuable than tax perks.

Moretti is not a household name, though his work is increasingly influential. One of the people he has influenced is Moret, the man in charge of Northern Virginia’s Amazon bid, who considers himself a disciple. As it happened—and unbeknownst to Moret at the time—Amazon executives were reading from the same text.

The story of how Northern Virginia landed the era’s biggest economic-development prize cracks open a window onto the mysterious corporate sweepstakes that captivated the nation. But more important, it provides a striking—and troubling—look into the future of our city and country as a whole.

To understand how Virginia’s team managed to access the thinking of Amazon’s executives, it helps to go back to November 2016, when Moret was hired by the Commonwealth. At the time, the Virginia Economic Development Partnership, the top job-development agency in the state, was in crisis—plagued by haphazard leadership, faulty data collection, and weak investment controls, and so badly mismanaged that, according to a state watchdog, it was vulnerable to fraud. Moret had previously run Louisiana’s economic-development department. In Virginia, his mission was clear: Straighten out the mess.

The balding, bespectacled Southerner launched a top-to-bottom review of the state’s economy to create a strategic plan. For the first half of 2017, he drove to nearly every county in the Commonwealth, meeting with local officials, chambers of commerce, and community leaders to discuss the state of industry. Virginia’s central economic weakness, he and his staff eventually determined, was over-dependence on the federal government. The question was how to reposition the Commonwealth for the future, and Moret knew just the person to call.

Enrico Moretti had joined UC Berkeley’s economics department in 2004, which gave him a first-hand look at the Bay Area’s tech boom. Year after year, he watched in bewilderment as startups and established firms flocked to a region known for enormous labor costs and stratospherically expensive real estate. It didn’t make any sense. Why would you run a company in Silicon Valley when—thanks to e-mail and instant messaging and the slew of communications technologies developed in that very same valley—you could operate it for a fraction of the cost in Des Moines or Detroit? The question became the central pursuit of his career. In 2012, he published a groundbreaking book, The New Geography of Jobs, that offered some surprising answers.

Highly educated workers, Moretti concluded, have become the knowledge economy’s most precious resource. “In the twentieth century, competition was about accumulating physical capital,” he wrote. “Today it is about attracting the best human capital.” But these college and graduate-school degree holders are not dispersed evenly throughout the country. Instead, they’ve been clustering in a handful of already-thriving cities—places like San Francisco, Raleigh, Minneapolis, and Boston—which, as a result, have also become magnets for forward-looking employers.

Northern Virginia’s proximity to federal regulators was one thing Moret’s team made sure to advertise to Amazon. They even drew up a map charting how close Crystal City was to the Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, and other agencies.

The cost of doing business in these “brain hubs,” as the economist called them, is indeed higher, but the brain hubs also offer something companies can’t find anywhere else. By serving as ecosystems for talented employees to learn from one another, generate fresh ideas, and spark innovation, they can create productivity gains that more than offset the extra costs of doing business. At the same time, the development triggers a powerful feedback loop, with the bigger paychecks and more abundant employment opportunities driving prosperity throughout the region.

Moretti’s book—which Barack Obama listed as one of his favorites of 2018—earned praise from public intellectuals from all quarters, including liberal New York Times columnist Paul Krugman as well as its resident conservative, David Brooks. The book also resonated deeply with Stephen Moret. Growing up, he’d moved from one struggling Mississippi town to another as his mother, divorced and raising him and his brother on her own, pursued her career as a pharmacist. Moret eventually obtained an MBA from Harvard and, after that, a doctorate from UPenn. His experience climbing from the rural South to the Ivy League ignited his fascination with the intersection of higher education and labor markets. He drew heavily from Moretti’s research for his own dissertation, which studied how investments in higher ed affected economic growth.

So naturally, when it came time to reimagine a new economy for Virginia, Moret wanted the Berkeley economist’s input. He called with an offer, and Moretti accepted.

The Virginia team worked through much of 2017 and concluded that the state’s biggest opportunity was in the high-tech sector. After all, as Moretti’s work shows, each new tech job creates an additional five positions in other fields. The economist advised that the best way to lure more tech employers was to build out the pipeline of highly skilled employees through investments in education. “That’s education at all levels,” Moretti says, “whether it’s pre-K or community college or local college.” He also suggested that Virginia partner with a public university and create a new innovation-and-technology campus, similar to the Cornell Tech institute in New York.

By the end of the process, the economist had been a profound influence on the blueprint for Virginia’s economic future. Then, just as Moret’s team was about to release their plan publicly, the big news broke: Amazon was launching a search for a second headquarters. All the work Virginia had just done with Moretti was about to become even more consequential.

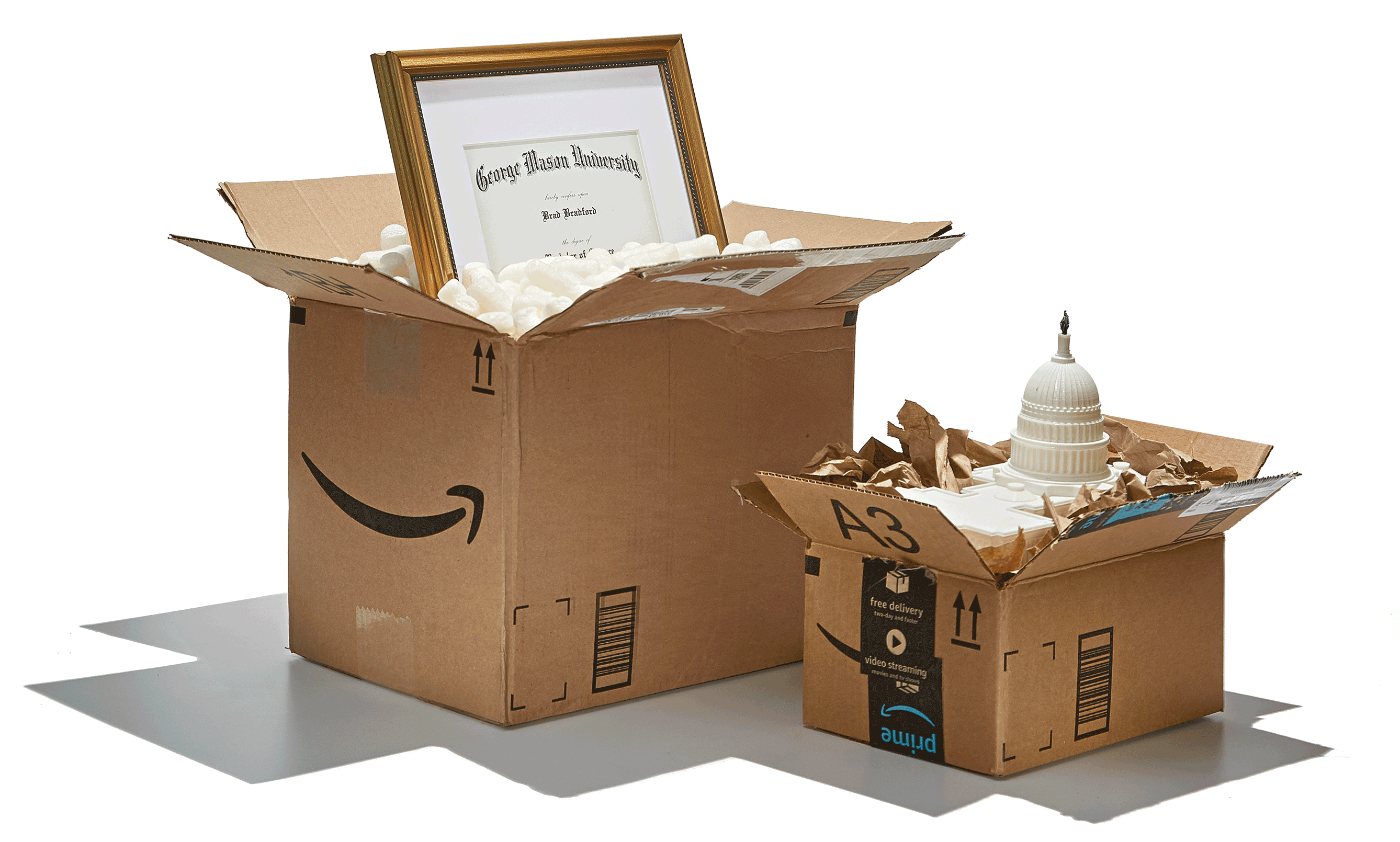

When it was first announced, The grand prize of the HQ2 sweepstakes amounted to a once-in-a-lifetime economic opportunity: 50,000 high-paying jobs and $5 billion of investments. Amazon received bids from 238 places, some of which appeared so desperate that they went to comical lengths to lure the company. Elected leaders in a Georgia city of 55,000 residents, as you might recall, promised to change its name to Amazon. The mayor of Kansas City left 1,000 five-star reviews on Amazon products—“Oh baby, this baby oil is a real treat!”—and each one noted the area’s attractiveness as a corporate headquarters. Atlanta offered to build an Amazon-only lounge at its airport.

As it happened—and unbeknownst to Virginia’s Moret— Amazon was reading from the same text.

Virginia did all it could to impress Amazon’s search committee, too. In February 2018, just before Amazon executives arrived in the Washington region for their first site visit, Moret’s team conducted a dress rehearsal at the exact same time and location that their actual pitch presentation would take place, in order to make sure they accounted for variables like sunlight and traffic flow. The development firm JBG Smith plastered the inside of its office-building elevators with life-size images of the interior of Amazon’s Seattle headquarters—“so that when they walked in there,” says CEO Matt Kelly, “it felt like home.” (One local figure spoke to Metro general manager Paul Wiedefeld and urged him to make sure Amazon got to ride on one of its newest, 7000-Series trains. Wiedefeld, who says he can’t recall whether the official was from Virginia, Maryland, or the District, responded by explaining that public transportation doesn’t work that way.)

But when it came to substance, competitors mostly organized their proposals around public subsidies. Moret’s team pitched the area as a brain hub.

Remember the heat map? The same McKinsey & Co. analysis that exposed Northern Virginia’s cost problems had also underscored the region’s strength: the intellectual firepower of its workforce. Nearly half of Northern Virginia/Washington-area residents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, making it the best-educated labor pool among the top contenders. And through their work with Moretti, Virginia’s team understood that an abundant supply of highly skilled workers was actually more valuable to tech firms than infrastructure upgrades or tax giveaways. In fact, when Moret’s team analyzed the Seattle market, they came to believe that a shortfall of qualified workers was one of the reasons why Amazon had launched its HQ2 search in the first place. “So why don’t we build a strategy that really focuses largely on that?” Moret thought. “Let’s dramatically expand our tech-talent pipeline.”

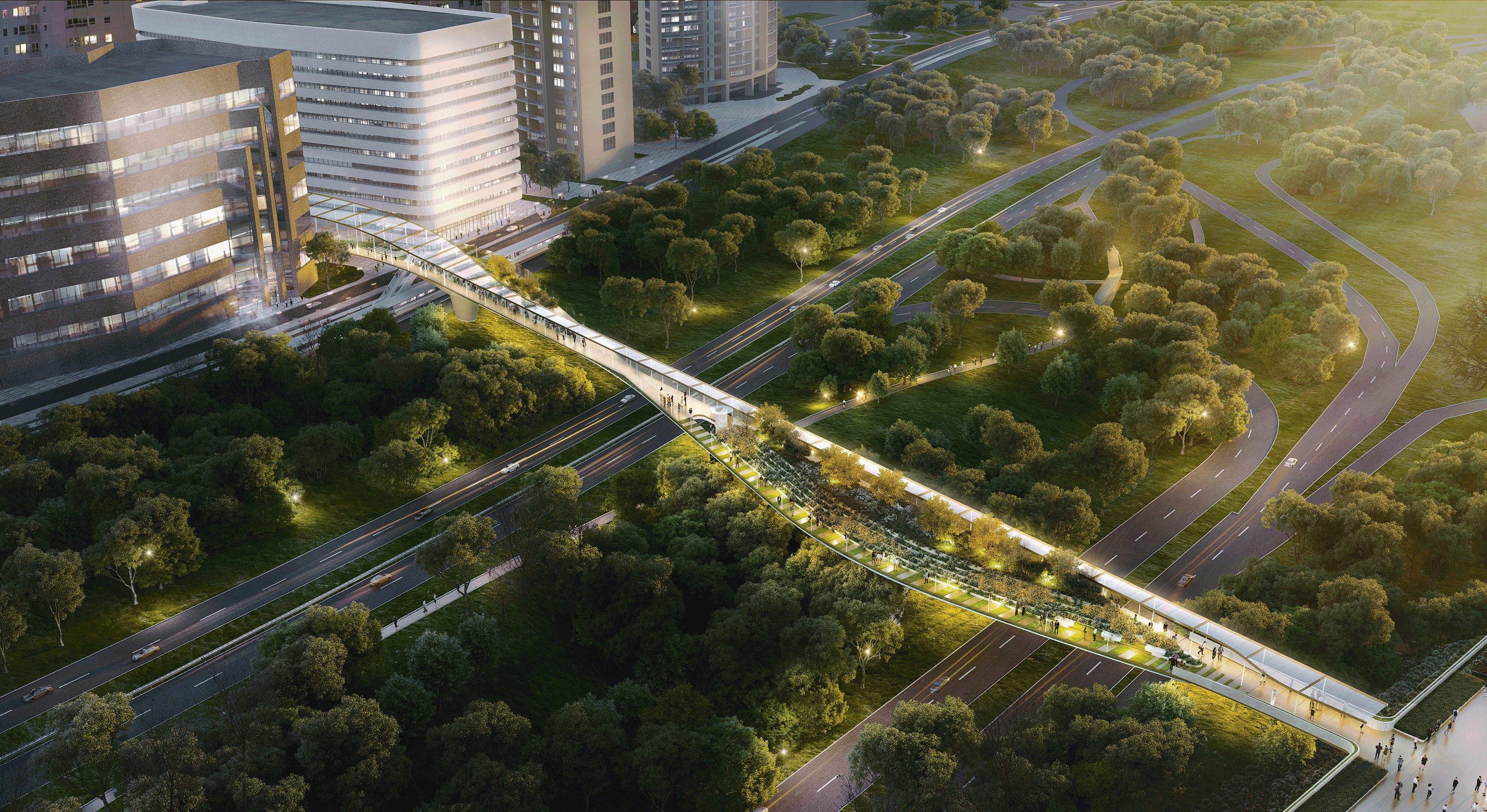

Northern Virginia’s ultimate proposal was centered around an effort to provide Amazon—or any other tech firm that wanted to come—with all the educated workers it needed, now and in the future. Moret’s team proposed increasing tech education from kindergarten through 12th grade, expanding university offerings to produce up to 17,500 new bachelor’s degrees in computer science and related fields, and building a tech campus that could produce the same number of master’s degrees. All told, Virginia offered Amazon only $550 million in tax breaks and $195 million in transportation improvements. But it pledged to plow $1.1 billion into tech schooling. According to Moret, it was the only place in the nation that made education the centerpiece of its pitch.

Moret and his colleagues heard nothing for several months after submitting Virginia’s proposal. They were so hungry for information that they began tracking the online betting markets. At first, things didn’t look good; in January 2018, the Irish bookmaker Paddy Power gave Northern Virginia 20-to-1 odds of landing HQ2. But around that same time, Moret got some encouraging intel. Through conversations with company officials, he says he and his team learned that a number of key Amazon executives had also read The New Geography of Jobs and were influenced by its ideas. “Okay,” he thought, “we’re on to something.”

Moret reached out to Moretti, the Berkeley economist, to discuss what the development meant for the HQ2 search. “What I really thought was that ultimately [Amazon’s] choice would be based on the type of underlying economic factors that I describe in the book,” Moretti says. “I always thought that the subsidies were going to be a not-so-important factor.”

At the same time, though, a second headquarters in Crystal City offered Amazon another benefit. As Washington has become sharply skeptical of Big Tech and newly concerned about monopolies, Amazon has amassed the industry’s biggest in-house government-relations team and hired President Obama’s former chief spokesman Jay Carney. It’s also trying to expand its government-contracting business by, among other things, pursuing a $10-billion cloud-computing contract from the Department of Defense. By plopping HQ2 into Crystal City—right next door to the Pentagon—its employees could become part of the Washington community, attending back-yard barbecues and school dance recitals with the very regulatory staffers and procurement officials whose decisions will determine the company’s future—and the very journalists and political strategists who might paint the firm as an Evil Empire.

Moret and his team, in fact, made sure to advertise this unique advantage in their proposal. “The high concentration of tech companies, federal agencies, and supporting organizations offer Amazon the opportunity to develop valuable future relationships,” they wrote. “Northern Virginia provides an unmatched place for Amazon to locate as it attempts to influence federal policies, particularly as it delves into complex areas of federal regulatory authority (e.g. unmanned drones).” Moret’s team even drew up and provided a helpful map charting Crystal City’s proximity to some of the most powerful agencies in Washington—the Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, the FCC.

Holly Sullivan, the Amazon executive who led the search, insists that political considerations played no role in the company’s decision and says Moretti’s research was one of many sources she and other executives read. “I would say this: that the book, along with other research that we did and items in journals that we read, including economic-development blogs—all of those factors were sort of taken into account for us to have a robust discussion.” Yet her explanation for why Amazon picked Crystal City might as well have been a blurb on the back of Moretti’s book. “We needed to find a location that had the day-one talent,” she says, “but also a location that has the resources and the sort of education ecosystem to build upon that tech-talent pipeline.”

Washington has mostly celebrated HQ2’s arrival, and years from now it will likely be viewed as the moment when the region transitioned from a company town to something much bigger. But along with this growth, if Moretti’s research proves prescient once again, we’ll also experience the dark side of Big Tech prosperity.

Even at half its original head count, HQ2 will reshape the region in ways you’ve probably already considered. Our 25,000 new neighbors won’t live just in Crystal City; they’ll drive up home values in Penn Quarter and support dry-cleaning businesses in Silver Spring. On a macro level, HQ2 will establish Washington, once and for all, as a national tech capital—a development that helps lessen our dangerous overreliance on Uncle Sam. According to AOL cofounder Steve Case, the politics of the era mean Amazon won’t be the last tech giant to expand into the area. “They’ve always had policy offices [here],” Case says, “but I think they’ll start concluding that having more of a significant presence matters.” In February, Google announced plans to double its Virginia workforce as part of an expansion of its data center in Reston.

It’s exactly the type of “brain hub” activity that Enrico Moretti would expect. But while his book helps explain decisions like Amazon’s, it also reveals the troubling consequences they trigger. As more and more tech-industry players migrate into brain hubs, the benefits of the knowledge economy become increasingly concentrated in a few isolated places. “A handful of cities with the ‘right’ industries and a solid base of human capital keep attracting good employers and offering high wages,” he writes, “while those at the other extreme, cities with the wrong industries and a limited human capital base, are stuck with dead end jobs and low average earnings.” The result, Moretti argues, is an America segregated not by race but by geography. Big cities keep getting bigger, rural communities fall further behind.

The bitterness directed at Washington may feel ugly now, but it’s likely only to intensify.

This divergence has clear economic implications: Workers in America’s most highly educated cities earn two to three times more than people working identical jobs in the least educated cities. But the regional inequality touches everything from personal relationships to public health. Moretti found that divorce rates in fading industrial capitals are higher than they are in brain hubs, and the average life expectancy of a man in Fairfax is a decade and a half longer than one in Baltimore. According to the economist, the “balkanization” of America is exacerbating the bitter polarization that has gripped our democracy. “Geographic segregation raises the number of people who live surrounded by others like them,” he writes, “and this is likely to reinforce extreme political attitudes.”

Geographic resentment will continue to grow, says Brookings senior fellow Mark Muro, as people in less affluent communities come to view brain hubs like Washington as home to a distant, economic elite that’s pulling further and further ahead. “I’ve been writing some things raising serious concerns about what this means for the viability of American consensus,” Muro says. “Because it is creating the sense that there are winners who keep on winning, and most places are doing only okay.” As the seat of the federal government and the home of a booming new high-tech sector, the Washington area will, for many, serve as a monument to our increasingly unequal nation. The bitterness directed at Washington may feel ugly now, but it’s likely only to intensify.

Sullivan, at Amazon, offers a less ominous read. “My take on the book is that tech jobs aren’t right for all communities,” she says. But, she adds, “I think anytime you’re doing a jobs investment of this magnitude, there are going to be ripple positive impacts that come from it. And I think that’s what’s important to recognize.”

For his part, Moret says he thought about the unequal implications of his work throughout the HQ2 process. After all, it was the chance to improve people’s stations in life that attracted him to the field in the first place. Although he understands how this type of job migration can widen inequality at the national level, he says HQ2 will actually help narrow the gap between thriving and struggling communities in Virginia. He points out that the deal won’t benefit just Crystal City—the educational investments are going to schools and universities throughout the Commonwealth, supporting residents of urban and rural communities alike. And of course, as Virginia’s economic-development director, he has a mandate to make sure the state beats out other regions.

“While we would love for all of rural America to win,” he says, “the part of rural America we’re most concerned about is the part in Virginia.”

This article appears in the June 2019 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)