One afternoon in 1973, Mick and Bianca Jagger decided to check out Washington’s buzziest restaurant. The couple were in town for a Senate event, and afterward they headed, as VIPs did, to the Sans Souci.

The Jaggers didn’t have a reservation, however, and the jam-packed French restaurant had a strict coat-and-tie dress code. What’s more, the staff—not exactly attuned to the rhythms of youth culture—didn’t recognize them. Madeleine Sosnitsky, the hostess at the time, had a feeling the would-be patrons were famous but couldn’t quite place them. So she went to talk it over with the maître d’. “He said, ‘They’re not dressed properly. Just tell them to go,’ ” Sosnitsky recalls. “So I did.”

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, the Sans—as people who could get a table often called it—was the epicenter of DC’s midday schmooze scene. Located close to the White House, it was a high-priced, white-tablecloth establishment where you could pick at sole amandine while nodding to Ben Bradlee, Henry Kissinger, or Ted Kennedy across the room. “Before the Sans Souci,” Washington Post columnist and humorist Art Buchwald once said, “there was no Power Lunch.”

The Sans was never lacking for royalty, whether of the political variety or actual monarchs. (The queen of Denmark and king of Greece both ate there.) It was the kind of place where you might see Gerald and Betty Ford celebrating a birthday or Andy Warhol stopping at Ethel Kennedy’s table to say hello. Elizabeth Taylor would drop by with future husband John Warner. Frank Sinatra came with Nancy Reagan. Sosnitsky recalls John Lennon and Yoko Ono bringing an entourage that included Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, and Anjelica Huston. (Presumably, the ex-Beatle had both a necktie and a reservation.)

Though it wasn’t DC’s only trendy spot—establishments such as Rive Gauche, Duke Zeibert’s, and Paul Young’s Restaurant had plenty of devotees—the Sans Souci was the place that became most associated with, to whatever extent such a thing existed, Washington glamour.

The Sans even showed up on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, in a 1976 episode that finds Mary Richards and Lou Grant traveling here for a seminar. “I’m gonna make reservations for you and your friend at the best restaurant in town,” Lou boasts. “You’re gonna go to the Sans Souci.” It’s “the place in Washington where everybody who is anybody goes to be seen.” Cue the laugh track: It turns out Lou doesn’t have any more luck scoring a table than Mick Jagger did.

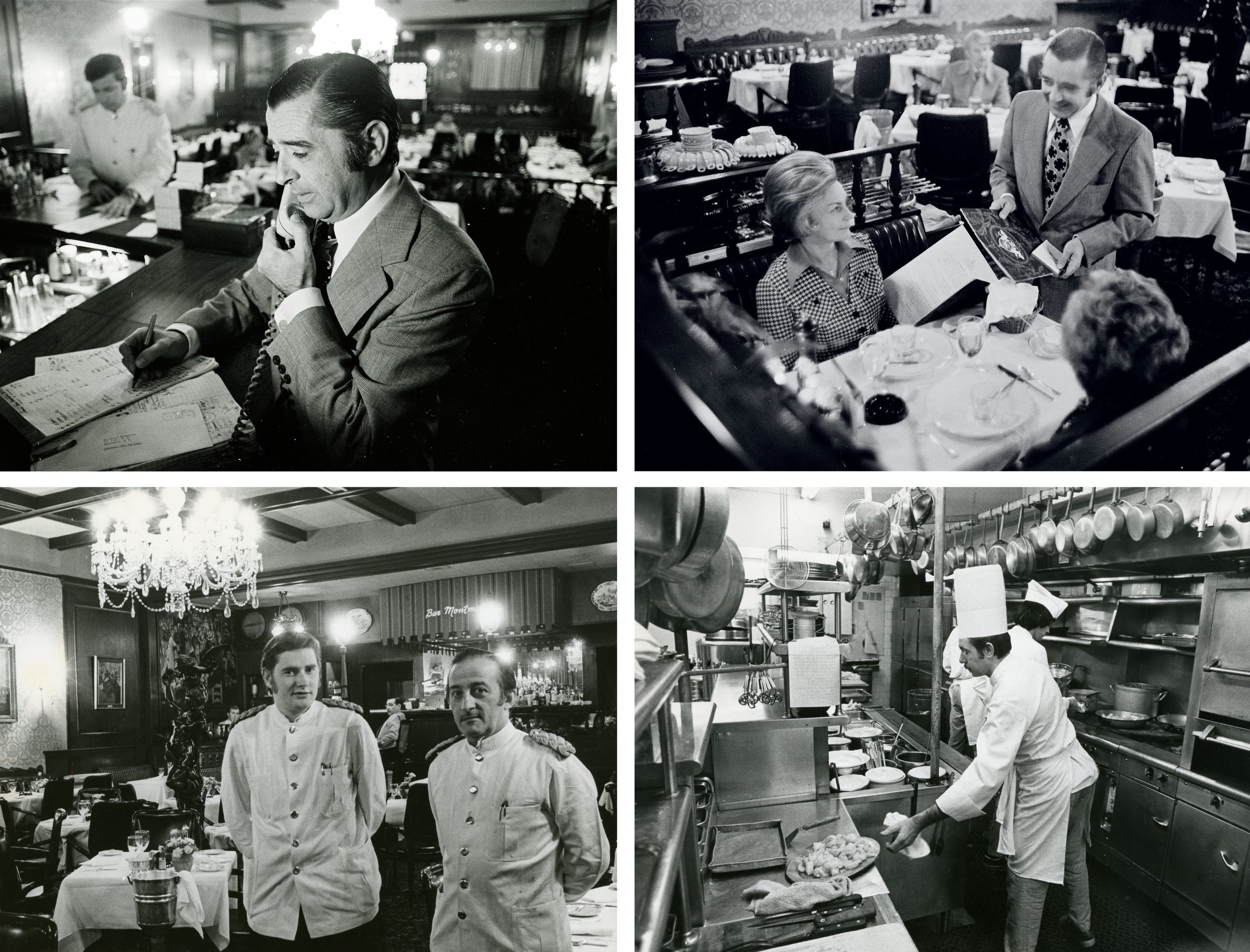

The Sans Souci served its first vichyssoise in early 1963, when it opened in a former greeting-card shop on 17th Street near Pennsylvania Avenue. Veteran chef Gus Diamant was in the kitchen, and a smooth, savvy Frenchman named Paul Delisle manned the maître d’ station. There were green-leather banquettes, imitation Renoirs and Toulouse-Lautrecs, and fresh flowers at every table. The waiters, wearing white jackets with gold-braid epaulets, wheeled carts for tableside preparation of Caesar salad, steak tartare, and crêpes suzette. In 1965, a meal of lobster bisque, endive salad, crabmeat en chemise, and crème caramel, along with a glass of wine and coffee, cost the equivalent of about $75 today.

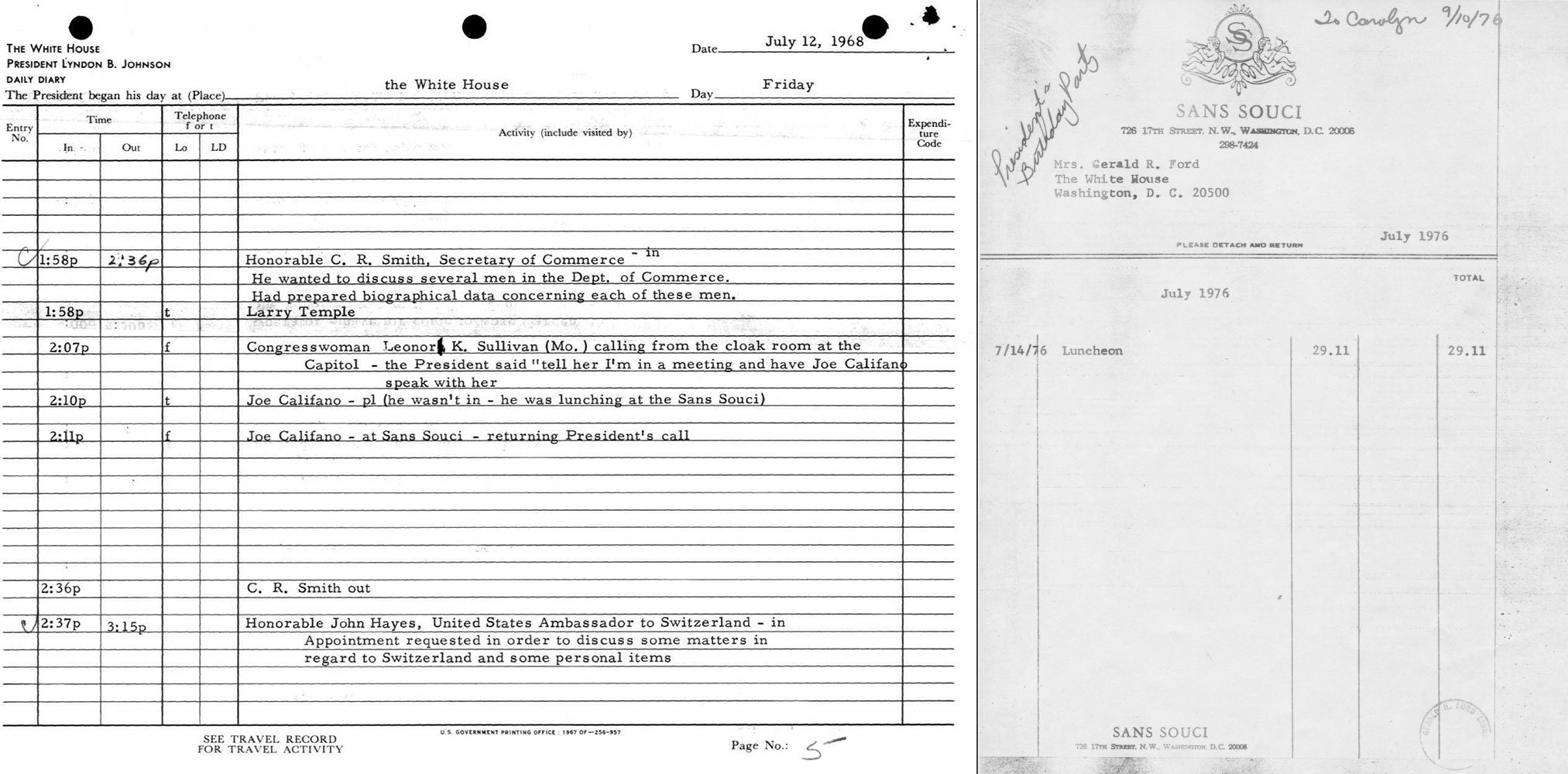

But the real attraction was less what was on the table than who was in the room. The Sans soon proved popular with the LBJ crowd. (White House press secretary Pierre Salinger was a regular.) By the early ’70s, the midday rush was overstuffed with familiar government and media faces: Katharine Graham, Ted Kennedy, Walter Cronkite, Henry Kissinger, Nancy Dickerson, Eugene McCarthy, Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, Nelson Rockefeller, and on and on and on. It was a relatively small space full of oversize egos, and Delisle—whose Gallic charisma and knack for hospitality made him a local celebrity—pored over two newspapers a day in order to keep track of who might need to be seated far apart at any given moment.

“It was like a private club,” says Sosnitsky, who worked there from 1971 to 1982. “Everybody knew everybody. Washington is such a particular place: Everything is who knows who, who goes where. We were always packed.”

The most reliable regular was Buchwald, whose reserved perch—table 12—was often the room’s focal point. Buchwald had a regular crew who dined with him, usually including Bradlee, the Post editor, and powerhouse attorney Edward Bennett Williams. Lunch could be a boozy affair, with conversation touching on “whatever was hot,” says attorney Joseph Califano, a partner of Williams’s—the famous DC firm had previously been called Williams, Connolly, and Califano—who often joined the group. “Buchwald never drank, but the rest of us drank at lunch, and ate and laughed,” he recalls. “I probably drank Manhattans. Can you imagine that? Somehow or another, we worked in the afternoon.”

During the Watergate era, the Sans continued to pull in the government and media elite, even as things got heated. “The mood changed from a friendly atmosphere to more of a tense atmosphere,” says Jean-Francois Ferré, who waited tables there from 1973 to 1976. “You could feel people being to a certain extent upset about what was going on. Everybody was kind of excited or kind of sad, depending on which side you were.” The restaurant even earned a mention in the All the President’s Men movie; a scene featuring Robert Redford, Dustin Hoffman, and Jason Robards was shot inside. (It didn’t end up making the final cut.)

The day White House counsel John Dean was fired and Nixon advisers H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman resigned, the Sans was unusually empty of the President’s associates. When former Nixon speechwriter William Safire walked in, the Post reported, everyone at Buchwald’s table started applauding. Delisle was confused, until Safire explained the joke: “It’s because I’m the only one who has the guts to show up.”

Sosnitsky likes to tell a story from the late ’70s about a birthday celebration for Rosalynn Carter, during which an unlucky waiter accidentally dropped a poorly balanced cake on the First Lady. “She was very nice about it and laughed,” Sosnitsky says. “The waiter was so upset he passed out.”

But while big names still came, the Sans had started to lose some of its gloss. In general, the Carter administration favored a less fussy vibe, heading out for, say, a turkey-bacon-and-avocado sandwich at the Class Reunion on H Street. “As if we didn’t have enough to worry about in Washington,” Buchwald wrote in a 1977 column, “it is now rumored that the Sans Souci restaurant is no longer the ‘in’ restaurant since the Carter crowd arrived in town.” He claimed to be unconcerned by this development. “The real problem for all of us,” he sniffed, “was that no one knew what a person from the Carter White House looked like, and even if he did come there we wouldn’t be aware of his presence.”

A bigger blow came in early 1979, when Delisle, the maître d’, decided to move on, apparently due to a dispute with Bernard Gorland, who owned the restaurant for most of its run. “He left,” says Califano, “and the place sank.”

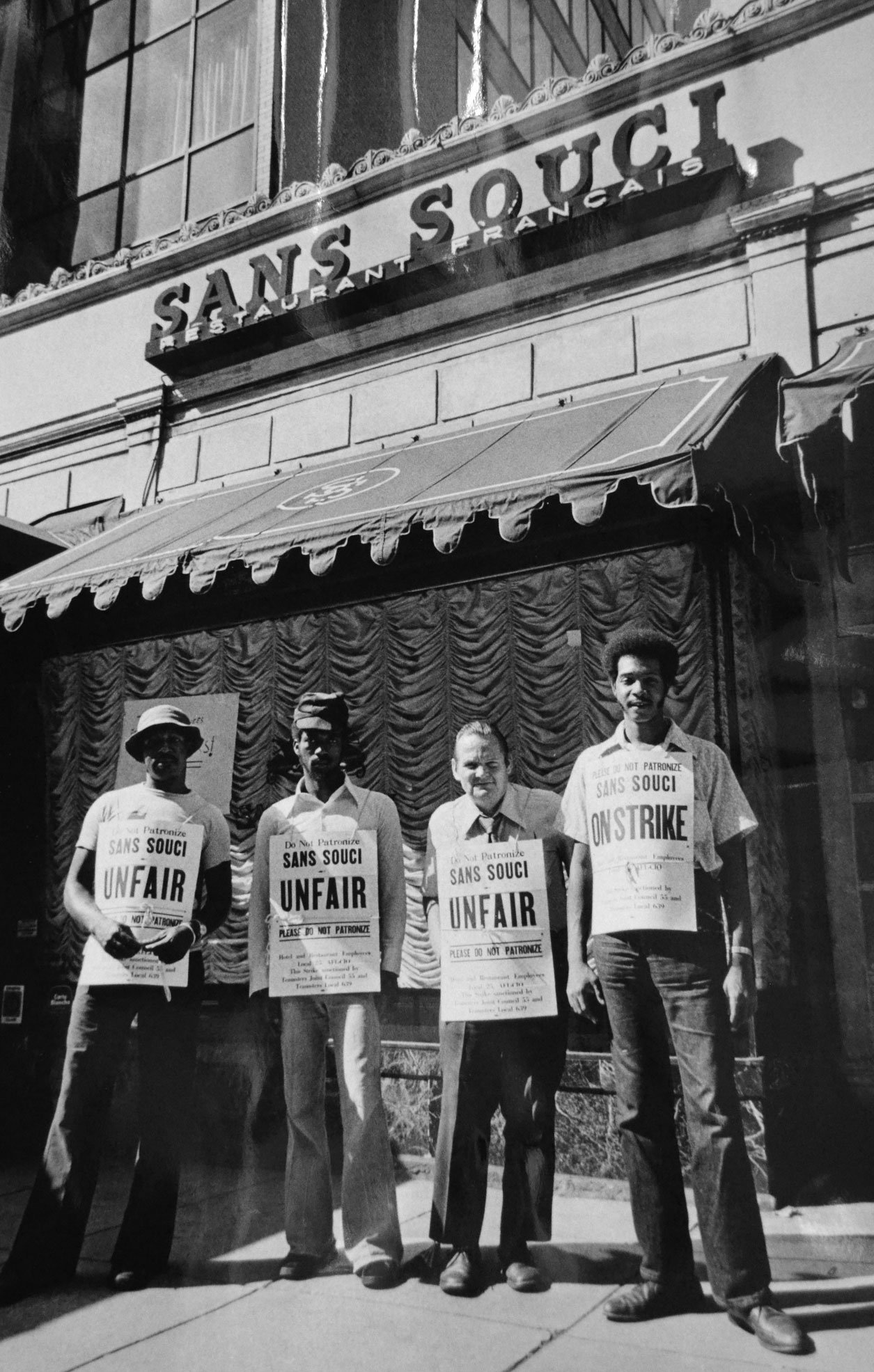

Buchwald took Delisle’s absence so hard that he decided to end his tenure as the place’s foremost patron. “With Paul’s departure, the Sans Souci became just another place to eat,” he lamented in another column, “and I had no choice but to fold up my table and leave.” A long-running labor dispute didn’t help; beginning in 1977, the Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union picketed outside for two years, pushing management to allow Sans workers to organize. (They eventually did.) “When you’re up, you’re up, and when you’re down, you go very quickly down,” says Sosnitsky, whose then husband, Pierre, replaced Delisle as maître d’.

Toward the end, the Sans attracted more tourists than insiders, and it was no longer difficult to get a reservation. Sosnitsky recalls one phone call from a man who said he wanted a table. When she told him they could accommodate his party, his tone suddenly changed. “Ha ha, now it’s no problem,” the man sneered. “Don’t you remember when I used to call and you always said, ‘No, we’re booked’?” Instead of making the reservation, he hung up on her.

The Sosnitskys departed in 1980, later opening Pierre et Madeleine in Vienna and then the Eiffel Tower Café in Leesburg. Delisle died of a heart attack in 1983. The Sans Souci, meanwhile, closed for good that same year, after having attempted a couple of reinventions. (A Hail Mary take on Italian—as Il Nuovo Sans Souci—was a flop.)

The Sans was eventually torn down and replaced by—what else?—a large office building. But if they’re inclined, today’s White House staffers can still head over to the site of the old Sans for lunch. The former home of Washington’s most powerful restaurant is now a McDonald’s.

This article appears in the July 2019 issue of Washingtonian.