I start the CIA Field Tradecraft course in the fall of 2005, learning the basics of elicitation, dead drops, bumps, brush passes, and surveillance detection. My small band of classmates and I run around DC at all hours of the day and night, marking signal sites with chalk and identifying the license plates of cars that trail us, sorting the training surveillants from the real ones, high on the fact that the civilians around us are carrying on with their normal days, oblivious to what’s happening right in front of them.

We’re given our first operational assessment: a bump, which means finding a target of interest in some public place and manufacturing a reason to get him or her talking. The aim is the much-coveted “second meeting”: an opportunity to continue the conversation somewhere else at some later date; this offers the operative the chance to build a relationship and, with it, access to whatever information the target might hold. I know from my time at the Agency’s Counterterrorism Center how precious that information can be. The location of a detainee, delivered hours before she’s to be beheaded. The name of a seller on his way to provide Soviet-era tactical nukes to a contact in al-Qaeda. The security loophole that Hezbollah plans to exploit to walk catastrophic biological agents out of a scientist’s deep freezer.

The targets we’re given during training are all characters played by case officers, the real-life, battle-hardened spies we trainees aspire someday to be. Some play the roles out of a sense of duty, passing their skills on to the next generation. Others do it out of exhaustion, craving a plumb three-year tour back home. The rest do it by way of penalty box, paying their dues after screwing up—or screwing someone—somewhere out there at the tip of the spear.

Our instructor drops folders on the tables in front of us, one each, all black. Mine opens with a photo of a middle-aged Gorbachev look-alike, minus the port-wine stain, leaning against the bar in a crowded pub. The write-up is sparse. He’s a Kazakh civil servant, it says. He knows about an imminent attack to be carried out with his government’s blessing. He has objected—privately, of course. He was ignored. The local station believes he might be a viable target.

Beyond that, there are only a few words of bio. He went to the Kazakh-American University in Almaty and studied business, with a minor in film. He collects American baseball cards. He has a dog. Tacked onto the end is a surveillance report. His home, the ministry, the home of his lover. Sometimes, on Sundays, he likes to go to Panera Bread. I smile at the awkward allowance for a location near the training center. Guess that’s where I’m headed. My eye scans the rest of the page. He sits in the back, it says. He always orders the pie.

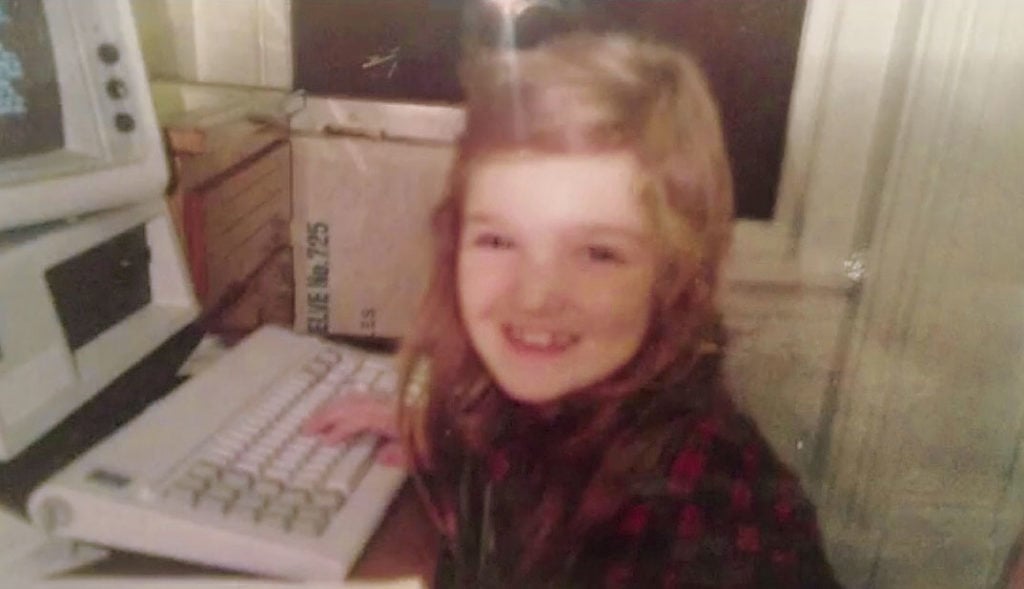

I pull into a spot in the Panera parking lot in Northern Virginia. I’m driving a training car, a rented Dodge Stratus, designed to safeguard my cover from any real-world surveillants sent by the Russians or Chinese to get a jump on identifying the CIA’s next cohort of spies. Fair enough—my rust-bucket Jeep is pretty identifiable. I glance in the rearview mirror. This is going to be our first graded exercise. My reflection doesn’t inspire confidence. I assess myself as a stranger might: blotchy skin, nervous eyes, the puppy chub of childhood still in her cheeks. Every movie I’ve ever watched suggests this is not what spies look like. But then I guess spies who look like spies don’t get very far.

We run around DC at all hours, high on the fact that the civilians around us are oblivious to what’s happening right in front of them.

Inside Panera, a line of Sunday brunchers snakes toward the door. I scan the room over the top of a menu, feeling vaguely ridiculous. The weekend yuppie crowd sprawls across tables and chairs. No sign of a cranky case officer posing as a Kazakh informant, pretending not to know I’m there. For a minute, I wonder if I’ve dreamed the whole thing, the way crazy people always think they’re surrounded by the CIA. Then I see him. Sitting in the back at the coffee bar, shoulders hunched, as if nursing a finger of whiskey.

This is it. My first opportunity to mess something up so badly that I get kicked out of the program. I draw breath and head toward him. The stool next to him is free—a courtesy for a new student, I’m pretty sure. I sit down and set a laptop and a book on the bar. He’s waiting for me to make the first move. I let him wait. In part because I’m terrified. And in part because I think it seems more natural that way. I open my laptop to an e-mail template and begin typing a fake note. “Thanks for the heads-up,” I tap to a fictional correspondent. “Given my connections in Washington, I feel a responsibility to help—I’m sure you understand.” I leave the cursor blinking there for a minute. I can feel him stealing a glance at my screen. I force myself not to look for his look. Instead, I sigh. Wait a beat longer. Then hit the keystroke combo to lock the screen.

“Do you mind?” I ask him.

He looks startled.

“Watching my things,” I say. “Would you mind keeping an eye on them while I use the restroom?”

He glances at the laptop, the book, back to me. He nods. The book is a prop I’ve created by wrapping a novel in a handmade cover that reads Rat Pack Chic: Glamour, Freedom, and the Advent of American Cool.

In the bathroom, I pull the door shut and start counting: One, two, three. I look in the mirror, examine my reflection again: Fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. She looks better this time. Twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-four. Like maybe she just might make it through this thing alive. Twenty-eight, twenty-nine, thirty. I open the door and clock him right where I left him, eyeing the picture of Dean Martin and Sinatra in mid-croon.

“Thanks,” I say and sit back down. We fall silent for a beat. It’s unbearable, the waiting. Finally, he says, “Those were the days, huh?” and nods toward the photo on the book’s cover like a spurned lover gesturing toward the girl who passed him by.

“Weren’t they, though?” I say. “I’ve always kind of wished I were born back then. I collect their letters.” I give him a shy smile. “The Rat Pack. You know, I mean I buy their letters and things when I get the chance.”

His face brightens. “I’d love to see those sometime.” He’s making this easy.

“Well, I’ve been planning to digitize them, you know, make them available online. Seems like such a waste for them to be in my desk drawer. But I haven’t gotten around to it yet.”

“That’s too bad,” he says, and I can hear the opening in his voice.

“But you know, I’d be happy to give you a look. You’ve been so kind, watching my things and everything. And I love meeting other people who appreciate the good old times. When things were . . . .” I pause. Glance at the television screen in the corner. “Simpler.”

“There I also know what you mean,” he says as the news anchor turns to talk of terrorism. “I’d be happy to have an hour’s escape in the company of Frank Sinatra.”

I smile. “It’s a deal, then. How can I reach you?”

He begins to give me his phone number, then stops and stares at me for a second.

“Helluva first meeting, kid.”

He’s broken character. This is how the exercise ends, I guess. The Kazakh evaporates and only the case officer remains, with the Brooklyn still in him. “Nice approach, asking me a favor. Most of your idiot comrades just sidle up and blurt out some awkward conversation starter like they have geopolitical Tourette’s. Why the Rat Pack?”

“You . . . he . . . collects old US baseball cards. I figured having some of those was a bit too on the nose. But, you know, Joe DiMaggio, Marilyn Monroe, Sinatra—it felt like the same vibe somehow. Servicing some sense of nostalgia. Some yearning for a world that he worries has disappeared.”

The guy’s laughing at me now. “Regular Dr. Freud,” he says with a shake of his head. “But you’re right. A good case officer is as much psychology student as he is James Bond.”

“Or she,” I say.

“Indeed.” He pulls an assessment paper out of his back pocket. There are a dozen or so categories that students are to be judged on. Beside each is a box to check: Satisfactory, Less Than Satisfactory, Unsatisfactory. There is no Good. In this business, it’s survive or not. Thrive is not an option. He clicks open his pen and draws a straight line down through the Satisfactory column. At the bottom, in the section for notes, he writes, “All aces. A velvet hammer. Might just have found her calling.” Then he folds the page in quarters, hands it to me, and walks out.

My two closest Agency brothers—Mike and Dave—are waiting for me at Ireland’s Four Courts, a mock old country pub along Northern Virginia’s commuter corridor. They also passed, but each with a smattering of Less Than Satisfactorys—or Lesters, as they’re lovingly known. We peruse one another’s assessment sheets as we drop shots into our pints of Guinness. “The velvet hammer, eh?” Dave says. From then on, that’s what he calls me.

I deploy to “The Farm,” a secret base in outstate Virginia, with no communication home for six months, for my last round of training. My friends and family all believe I’m on assignment for the boring multinational where they think I’ve been working as a consultant—my cover until now.

When I finish this course, my training branch chief informs me I’ve been selected for one of the hardest and most coveted assignments in the Agency: I’ll be under non-official cover. Most CIA operatives deploy under diplomatic cover, pretending to be a low-level secretary at the US Embassy by day and working their espionage targets at night. That works for Cold War–style spycraft, recruiting members of foreign governments, but terror cells don’t much care whether someone is a US diplomat or a US spy—if they work for the US government, they’re a target. To infiltrate terror networks, to run and recruit terrorist assets myself, I’ll need a better cover than Beltway consultant. Businesswoman, artist—something that doesn’t reek of Washington.

“You’re a 25-year-old white girl,” my boss says back at Langley. “Don’t hide from that. Lean into it. What reason could you possibly have for being in Yemen or Libya or the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan?”

There’s aid work, but that cover has been used a thousand times before. And each time it is, it erodes the ability of real aid workers to do their job without falling under local suspicion. There’s journalism and documentary filmmaking, a nod to my history freelancing in Thailand and Burma. But that cover holds for only so long until it becomes obvious your work isn’t showing up on the wires.

“What about art?” I ask.

“Go on.”

My parents collect it, I explain. My sister is studying it. Anyone would believe I’d be drawn into that world, too. With artists from emerging scenes like China and India making record sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, it would make total sense for a young entrepreneur to be out scouting new markets in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. If China’s anything to go by, I say, governments and criminals alike love using the art scene to launder money, so there’s real access there. It might even allow me to brush up against some antiquities dealers hawking war trophies. Most of all, it would give me a reason to run around the boonies with sealed boxes and bags.

He mulls this over for a minute, then nods.

“Sold. Family history makes it believable. And the art market’s just dirty enough to give you entrée to the netherworld when you need it. Get it set up.”

“Getting it set up” involves hundreds of hours of work. There’s the preparation of fake business plans and financials to ensure that I can talk mechanics if anyone should ask. There’s designing the website and creating the digital litter—search results that reinforce the company’s legitimacy. There’s the printing of business cards—my own and those of colleagues I would have met were this my real job. There’s the forging of expired conference passes to scatter in my backpack and the generation of a year’s past e-mail traffic with nonexistent correspondents, in case anyone should check my phone or hack my digital accounts. It’s the birthing of an entire identity, all to backstop one simple line: “I deal in indigenous art.”

Alongside the creation of my cover, I have a few other post-training errands to run. I stop by the Directorate of Science and Technology, known as the DS&T, to design my covcom—the covert communications system I’ll use to communicate with headquarters from the field. Most operatives rely on secure computers in the embassy’s station to send their cables, but as a NOC (non-official cover), I won’t set foot in the embassy door. For us non-official types, the DS&T teams design systems that can travel with us, embedded in our computers and accessed through labyrinthine combinations of physical trapdoors and online keystrokes, to be sure no inspecting customs officer can find them. Each is created from scratch with a given NOC’s cover in mind, and now that I have the art business under way, it’s time to get my covcom fired up to match.

Setting up my cover takes hundreds of hours—preparing fake business plans, creating digital litter, forging expired conference passes.

I sit with the engineers in their warehouse of technical delights and brief them on the finer points of my new business. They scribble notes with a pencil—the only low-tech item in the room—and, a few weeks later, present me with a phone and a long list of instructions, to be carried out in the correct order to unlock the covcom hidden inside. There are buttons and switches interspersed with keystrokes and visits to art-related websites and edits to pictures of the Louvre. It’s a spy-tech Konami code, like the combinations of commands that unlocked secret power-ups in the Nintendo games we played as kids. There’s a cheekiness to it, hiding a portal to the heart of the government’s secrets right there in plain sight of every adversary I’ll meet. I tuck it away like a Batphone, my secret connection to the cavalry back home. It is my talisman. It makes me feel less alone.

Down the hall in the DS&T is an altogether different room, hung with fabrics and leathers and lace. It’s the CD shop, where tailoring wizards add concealment devices to briefcases and dresses and coats. They’ve pulled a Tumi bag in preparation for our meeting. “These are my favorites,” the woman tells me. “Professional, anonymous, well heeled but not luxurious.” I grimace at its plush smugness.

“Do you have anything a bit more hippie-backpacker save-the-world art lover?” I ask.

The woman smiles. “Stand by,” she says and disappears into the fabrics. When she reemerges, she’s holding a woven cloth hobo bag, straight out of a Thai night market.

“Bingo,” I say, and she winks.

When I return to pick it up, she walks me through the three compartments she’s added, each a different size and accessed through its own particular combination of thread tugs and flap pulls.

“Magic,” I say.

“Just a regular old Muggle. Doing my best.”

The last tech stop is a few floors up in a mirrored makeup studio hung with latex noses and glasses and wigs. I’m there to be fitted for light disguise—a ridiculous getup, not much better than a drugstore Halloween costume, intended to throw surveillance off the trail during a test run of a route.

“I’m not sure anyone’s gonna buy this,” I say to the man as he stuffs the last of my hair under a Brigitte Bardot bob.

“It’s for from far away,” he says in a French accent. “Try these.” He adds a pair of spectacles. They’re more preposterous than the wig, but somehow the combined effect cancels out to an awkward but non-alerting librarian.

“Fine,” I say. “Can’t imagine using these, to be honest, but seems as good a getup as any if I have to.”

The man looks miffed but tags them with my Agency ID number and pads off to find some clay to make a mold of my face. I’m pretty sure he leaves me caked in the stuff a beat longer than he has to, lying on my back and breathing through a straw. “Don’t piss off Guillaume,” I remember my boss telling me when I spotted a crooked latex nose hanging from his cabinet. Now I understand what he meant.

Reality gets more and more distant, obscured by the ever-thicker veil of my new cover. I take my first trip under its protection and then my second. At the beginning, I run through the details obsessively during each flight, preparing for possible grilling at customs when I land. But soon I come to slip in and out of it more easily, as with a softening pair of shoes. The real world feels farther and farther away.

I go to brunch with my family at a cafe on the Potomac River and tell them I’m going to try my hand at dealing in indigenous art. They don’t take much convincing. They had never understood why I’d wanted to work for a multinational anyway. Seeking out cultural expression in far-off lands is a much better match with their expectations of me.

“Now, that’s the rebel I know and love,” my sister chimes in. I’m relieved when they buy it. If they do, maybe al-Qaeda will, too.

“Just don’t get thrown into prison,” my mother jokes.

“Not much chance of that,” I laugh. Of all the lies I tell them, that one is the biggest.

From the book “Life Undercover: Coming of Age in the CIA” by Amaryllis Fox, to be published October 15 by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2019 by Amaryllis Fox. Names, locations, and operational details have been changed to safeguard intelligence sources and methods.

This article appears in the October 2019 issue of Washingtonian.