Debbie Harry has been famous for more than 40 years, but the Blondie frontwoman still considers herself a private person. “I know it probably sounds ridiculous, but I’ve managed to keep a certain amount of my life very private,” she says. “And I think that when I realized what I would have to do to make this book something that I could live with, that I would have to go a little bit more public.”

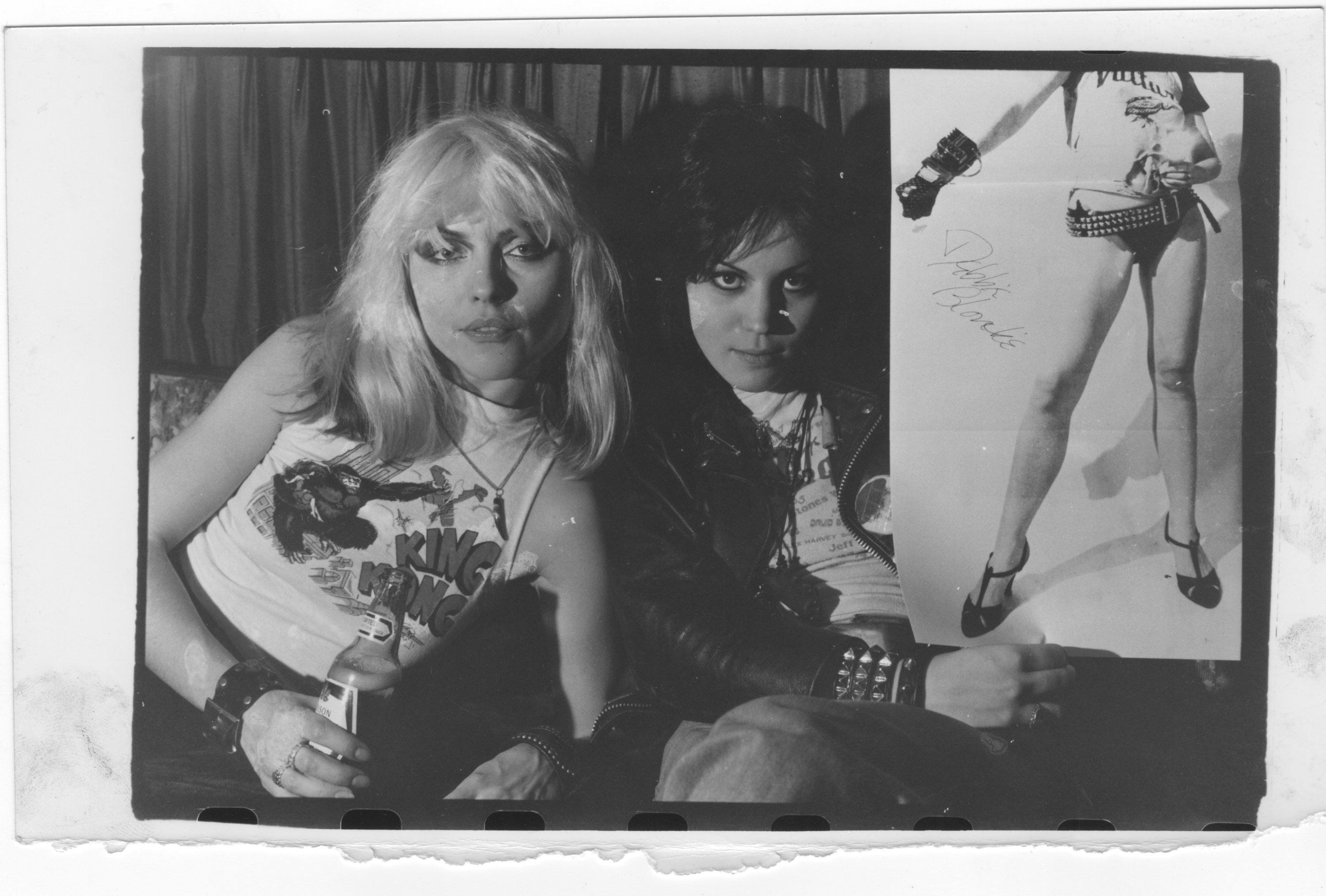

In her new book, Face It, Harry, who is 74, lets fans get to know her better. The memoir, which Harry wrote with British music journalist Sylvie Simmons, covers a lot of ground, from her upbringing in New Jersey to the early days of Blondie when the band performed at legendary New York clubs like CBGB. Part autobiography and part picture book, Face It incorporates photographs of Harry throughout her life, along with a vast collection of fan art she’s collected over the years. On December 4, Harry will discuss the book at Sixth & I in conversation with Chris Stein and the book’s artistic director Rob Roth. Washingtonian caught up with Harry ahead of her stop in DC.

You had initially resisted the idea of writing a memoir. Why you decided to write one at this point in your career?

Well, I guess there were several different reasons that occurred to me over a couple years’ period, cause I actually did work on this for quite a long time. What with recording and touring and promotion of albums, you know, it just took me at least four years to get this all organized and out to the publisher and getting all my ideas together. So, I think after a while I sort of got used to the idea.

In the book, you write, “I still have so much more to tell, but being such a private person, I might not tell everything.” How did you decide what you were gonna put in and what you were gonna keep for yourself?

I think a lot of the stuff that I haven’t really put in there has to do with really deep personal motivations and maybe some neuroses [Laughs]. But I think that I covered a lot of ground, and it’s really relevant to what people really want to know about Blondie and about the origins and what my thinking was behind creating this collection of characters and wanting to have a band. All of these things are very important to me. Plus, I think in the process of recording these interviews with Sylvie that the book took a direction because of her journalistic approach to interviewing, and after a while I felt comfortable with that. I think at first I didn’t, but after working with her for a while, it seemed to be taking a comfortable or reasonably comfortable direction for me.

Reading the book, I was struck by your descriptions of New York in the 1960s and ’70s, from you working at Max’s Kansas City to watching the Velvet Underground at the Balloon Farm. That’s a time that is often romanticized. What did you make of it looking back?

I felt lucky that I had been around for that. Although, personally, I was struggling with satisfying my curiosity and my desires and financially it was always a struggle for me. But I was very fortunate to be around during those times and meeting all these crazy people and colorful personalities and all of this great music. It was a really exciting time. I mean, I think that New York is always exciting. I think there’s always great stuff going on, and it seems now bigger than ever because they’ve got everything going on over in Brooklyn and it just seems like New York is New York no matter what.

You write about Blondie being a character. Do you feel like people saw you and the character as one and the same, or like people were able to separate the two?

I think that depends on how well you know a person. I feel that all performers have a public persona and a sense of character about themselves as well as their personal life and their more intimate personality that they share with friends or lovers. So, in that respect I think it’s fairly common. But I think for Blondie especially, at that time, since there were sort of prescribed personality values that were applicable to girls and to women, and so I used some of that in the way that I presented Blondie. And I still do that for obvious reasons, because it’s connected to the material and it’s connected to this–I put it in quotation marks–”character” of Blondie.

Did you feel like the book was a way for people to get to know you better outside of that?

Absolutely. And that’s part of the reason that I wanted to include the fan art…I think the fan art, for me, is such an important part of the book, because it’s sort of like virtual reality and it’s a virtual exchange at a time when virtual reality didn’t really exist, didn’t really have a name.

I was curious why you decided to include that.

Oh, I always intended to. I mean, after saving it for all these years, I always intended for it somehow to be put into a folio and put out on our website or online. I’m very interested in art. I am very interested in perception, and part of the thing that used to disturb me about getting fan art was that it was always portraits of me, and I had also always sort of wanted to get portraits of the people that were actually making the art…I found that within those drawings that people sent to me of myself, there’s always a little quantity of themselves. And the reason that I know about this is because of trying to do portraits of other people, where I would notice in the final version there was something of myself within their face. I know it’s kind of crazy and it’s very subtle and maybe a little bit psychedelic [Laughs]. I’m not afraid of that.

What has touring with the book been like? How has it compared with being onstage in a musical capacity?

Well, it’s been much more intimate. Because the audience gets to do question and answer and not just listen to a lot of music and songs, it is much more intimate. For me, as a performer, I find doing the music shows much more of a physical relief, and doing the conversation thing is more like doing a play. Although, it’s not fiction. It’s real. We’re talking about our lives, we’re talking about people that we’ve known, people that we know in the present.

What do you hope people take away from reading the book?

I don’t know, for everybody it’s different. I don’t know if there’s any one thing. I think most clearly, it is a sense of not giving up on yourself. And to not to be afraid of mania.

This interview has been edited and condensed.