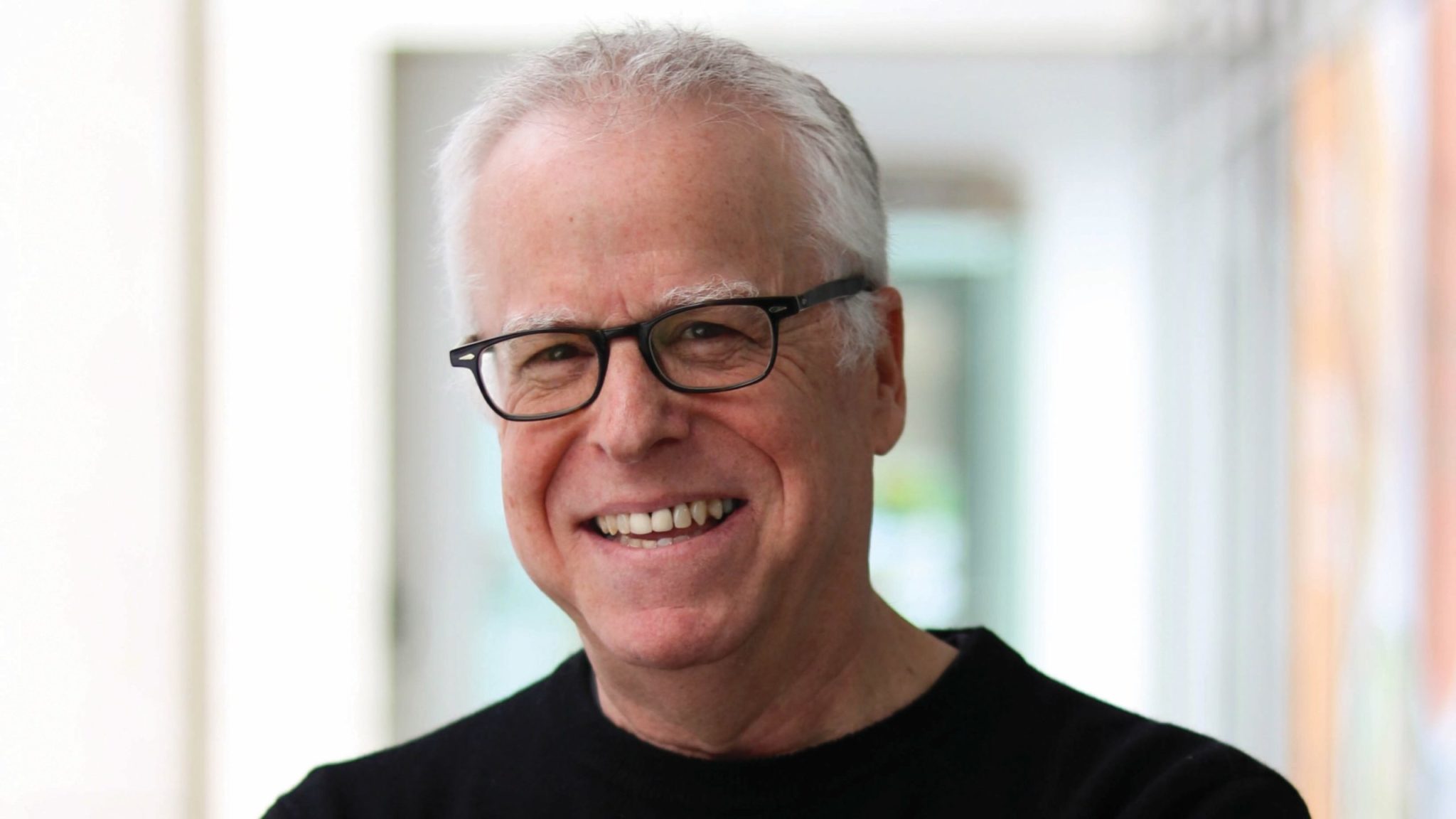

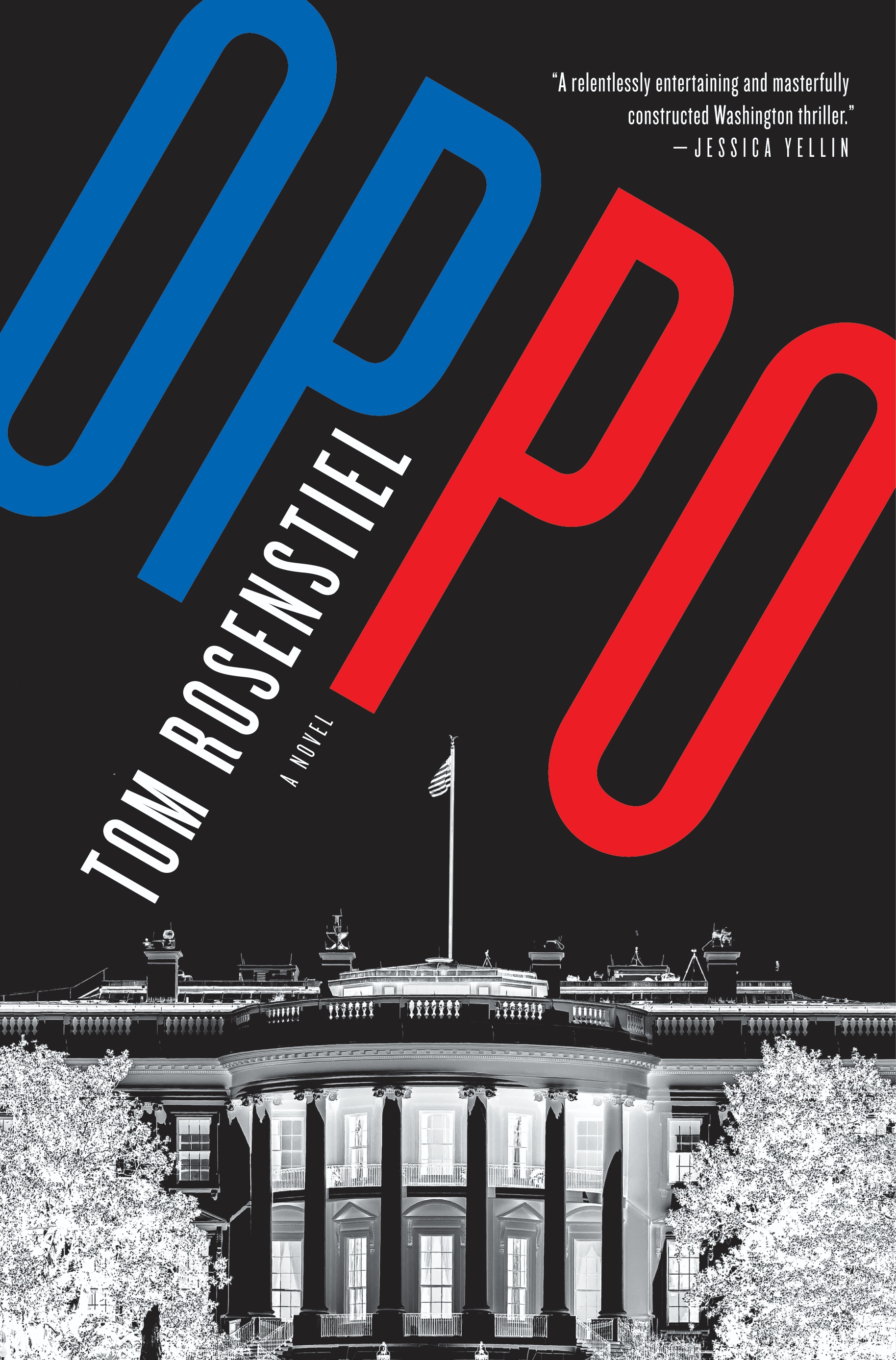

Tom Rosenstiel’s new book comes out this week and plunges into the no-longer-so-shadowy world of Washington’s opposition-research business. Rosenstiel, who in his day job is the executive director of the American Press Institute and is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, is a former reporter and has written many non-fiction books about the US news media and how information travels, but he’s somehow carved out a second career as a writer of thrillers—Oppo is his third mystery novel. We sat down with him at Stoney’s on L Street, Northwest, to figure out how he managed to do that.

So how did you figure out how to write mysteries?

When you write a piece of journalism, you have your notes, you have what you collected for that story. If it’s a magazine piece, you have what you’ve collected and what you’re trying to say. In my experience, writing nonfiction books, you execute the outline. Your ideas hopefully become richer but you’re still following the map that you wrote. [Writing fiction] is not a logical process because you’re inventing people who fill themselves out as you’re going along.

You don’t necessarily know what the story is.

I’ve discovered as I’ve wandered into the world of fiction that there is you know the spectrum between what they call “pantsers” and “plotters.” Pantsers are people who write by the seat of their pants, and plotters are people who plot everything out ahead of time. I’m so new at this that I’m clearly more of a pantser. And I wish I could be better as a plotter.

Do you have to write a lot of drafts?

I have a couple friends who are readers. They see the second draft. I make changes from that, and I send my editor the changes from that. What my editor sees as a first draft is probably my third. Because my first is so grotesque that no one should see it. And then my editor will give me significant notes, and I do what is probably a fourth draft. And then there are some final notes after that. I heard Michael Connelly talk once and say when he was in the newspaper business, your goal is to make your copy so clean that your editor doesn’t even touch it. He said when he stopped being a newspaper reporter and became a writer of crime novels he discovered that every book was made significantly better by his editor. And I’ve had the same experience.

How did you move into the world of fiction?

It was 2007, 2008 when I first started thinking about it. And my agent’s reaction was, You write journalism books. Why are you doing this? You’re not 30 years old. But someone in his office, a young woman in his office, said, Keep going. And really that’s all I needed.

Your second career reminds me of the dream of owning a restaurant: I would guess a lot of people in Washington would like to write a mystery.

I think so. If you like to read them you imagine yourself writing one.

Is this an escape plan for you, or is it a hobby?

It’s more than a hobby. It would be way too hard to be a hobby. You have be very jealous about your time, you have to do it every day. Seven days a week, my mornings are dedicated to this. I don’t do breakfast meetings. I don’t do phone calls early in the morning.

That’s a lot to squeeze out of a week.

I could do more—if I had more time I could do more.

If I wrote a tenth of the books in my “book ideas” folder, I’d be the most prolific author of our age! How did you do the research for this book?

I had a lot of conversations with people about oppo research and how that works now versus the way it did then. That world has exploded. If you think about ’88, Michael Dukakis, two of his staffers got the video of Joe Biden plagiarizing a speech by a British politician. And they leaked that video to reporters. Dukakis was so afraid of the backlash that he fired them. Even 15 years ago, if you wanted to do opposition research on somebody, it was expensive. You had to hire a private detective, it was hard to hide the money, there was a potential backlash if you were caught doing it. Now it’s so easy to do oppo research because of the internet, and then, when Citizens United came along, that Supreme Court decision basically meant third party super PACs could do the oppo research with unlimited funds. So you actually have oppo super PACs that just do opposition research on the other party. And they advertise it.

Your book is obviously mapped pretty closely to the world we’re in, but we’re also in a time when the reality of our political situation is weirder than you could expect readers to accept. When did you write this?

I wrote this book in 2018.

So in this moment.

Yeah. And the dates of when the primaries occur adhere to the dates in 2020. But it never says this is 2020. But you’re right. It’s a great challenge—first of all, you don’t want to have a Trump character. Because it would just be Trump. And he’s not that interesting because there isn’t a lot of character depth. He’s repetitive, you know what he’s going to do, he’s cartoonish or would be cartoonish in a book. What’s interesting about him is Trump as a reflection of deeper forces. What it says about us, him as a reflection of our fears. And those can play out, I think you can write about those forces, and I try to. They’re in the campaign and people can see the system falling apart. But the, the risk of that is the book seems like it’s a rumination on our times and not a story. It has to work as both. But if you told it as a story, if you tried to write a political mystery with no connection to our times, that would be just as weird.

Maybe people will be reading this a few years from now and this will all seem distant and an aberration or maybe it’s how politics are going to be from here on out.

I don’t think Trump will be how politics will be from here on out. But I think—you know, one of the things I talk about in the story is how elections—I went back and reread Teddy White’s The Making of the President 1960 when I was thinking about this book, and I even quote the book in the novel. White talks in that book about how elections are this sort of miracle of American hope. But they were a reflection of what we hoped the country would be. And I thought, okay, now our elections are a reflection of our fears. And at least with Trump, we’ve elected someone to hedge our bets against our fears or to shake things up because we feel things aren’t working. So that can still exist without Trump.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.