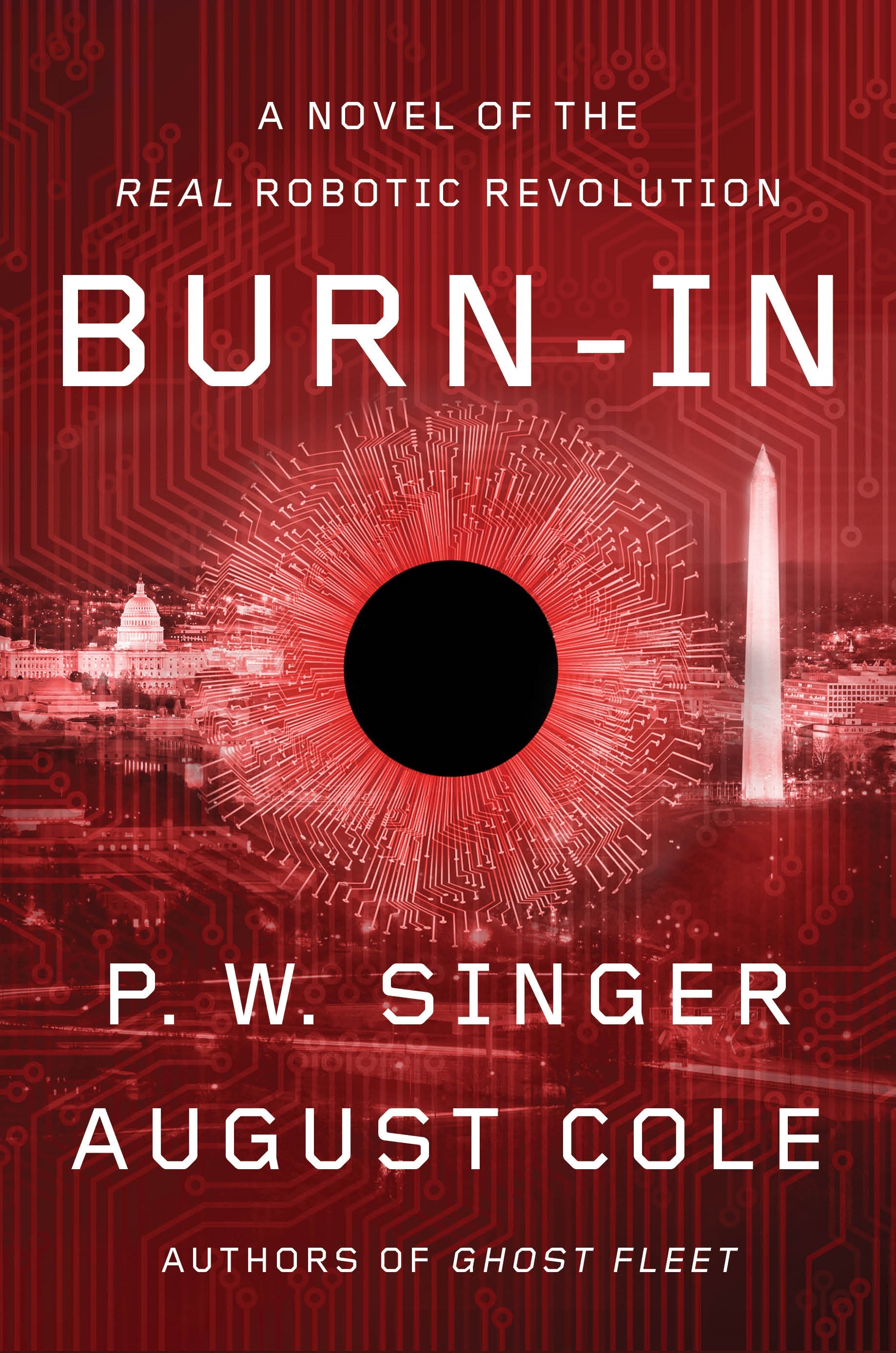

Burn-In, the latest futuristic thriller from P. W. Singer and August Cole, is technically a novel, but don’t call it science fiction: None of the technology—and there is a whole lot of technology—is made up. The characters and plot are invented, but the depiction of the DC of the future is based not on imagination but rather on extensive research. Set roughly 20 years from now, the book taps into existing tech, ideas under development, and current research, all meticulously footnoted throughout the text.

Singer, a strategist and senior fellow at New America, is an expert on defense issues, while Cole once covered the defense industry for the Wall Street Journal. (They previously teamed up for Ghost Fleet, a novel about what a war with China might look like.) Their defense credentials and intriguing approach have earned them a surprising collection of Burn-In blurbs, from David Petraeus to Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof to Garry Kasparov. We talked to Singer about how the book came about and what Washington could be like two decades from now.

This a futuristic thriller about an FBI agent who teams up with a robot. I assume there’s already a movie in the works, then?

[Laughs] From your lips to Hollywood’s ears. We’re hopeful of something like that but it has not yet formally gone out to Hollywood. The book is a mix of fiction and the real, so it’s a blend of the Washington, DC, of the future and Hollywood-esque scenes, but it’s all drawn from real-world research—things that either already exist or technologies that are going to be here in the next five or ten years. So you get the fun of a techno-thriller and along the way you learn about how AI works ,what will be the planned applications of it, what will be the political, social, business, security dilemmas that we’re all going to be facing. I’m a parent, so I think of it as akin to sneaking fruit and veggies into the smoothie. In this case, it’s a mix of entertainment and the latest research about important things that we all need to know.

A good example would be algorithmic bias. It sounds like this wonky, complex topic, but algorithmic bias is essentially when the AI spits out an outcome or takes an action that is biased in some way that it wasn’t originally programmed to do. For example, we’ve seen AI used to screen who should get bank loans, and it was screening out African Americans. The AI was being racist even though no one had told it to be racist. This is an incredibly important concept, but most people are not going to read an academic paper on algorithmic bias. Instead, we illustrate it through scenes like, for example, when an FBI agent is trying to pick a terrorist out of a crowd at Union Station. It’s an exciting scene, and yet at the end of it the reader walks away not just entertained but also understanding some of the concepts of algorithmic bias.

This is hardly the usual way people who work at think tanks try to get their ideas out into the world. What do your colleagues make of this approach?

There’s a long tradition of people in policy and politics writing a novel as a side enterprise. Some of them are really great, and some of them are not so great. [Laughs] But this is different in that it is actually part of the plan. It’s taking that research that you’re doing in the policy world and deliberately sharing it through this mix of fiction and nonfiction. Early on, I think there was a little bit of eyebrow raising, but then after the impact of Ghost Fleet, it was inarguable. It wasn’t just that people were seeing an influence on policy—it opened up a broader discussion of using this [type of book] as a new kind of tool. We call it “useful fiction,” or the more technical term is FICINT. For people in the government, they’ll recognize the terms of SIGINT, signals intelligence, or HUMINT, human intelligence, and these are the tools that spies and analysts use to explain and explore and analyze. What we’ve put forward is this concept of FICINT, and it’s taken off.

New America is a different kind of think tank—we very much have a focus on new ideas and lifting up new voices, and we’ve also made a strong push to explore how to communicate in new, more-effective ways. In a world that’s moving at machine speed, where there’s so much going on around us that’s hard to understand, it can be incredibly useful to have a guide to take you through that world. That is what narrative is—it’s actually the oldest technology of all. But it’s not just the complexity—it’s simply how much is going on. Important ideas, important research, are competing for attention. To put it bluntly, people are more likely to read an engrossing novel than a think tank white paper or an article in the Journal of the Association of Obscure Studies. [Laughs]

Burn-In has already had policy impact. The Cyberspace Solarium Commission is a Congressionally mandated bipartisan commission to essentially redo all US cybersecurity strategy. When they developed a report on the changes that the US needed to make in its cybersecurity policy, the commissioners were worried that the report would experience the same fate as all those other lengthy commission reports that had been written on terrorism before 9/11 that weren’t listened to until they were too late. And so in lieu of a traditional beginning to the report, they actually commissioned a short story from us that was drawn from Burn-In. The beginning of the report is actually this story read from the perspective of a congressional staffer who is tasked with writing legislation in the wake of a massive series of cyber attacks that have crippled Washington, DC. So the idea was to drop the commission’s target audience into both a public and personal nightmare experience with the idea of inducing them to ponder what they ought to do in order to avoid going through this—right before they then read a series of policy solutions.

What kinds of policy changes are hoping the book might bring about?

Steve Mnuchin said AI is not something that we have to care about for “50 to 100 years.” I’m sorry, it’s here now and it will be an issue that we all have to wrestle with. In many ways, we’re going through an industrial revolution like what happened with the rise of steam engines. But it goes beyond it, because in this case it’s a tool that is intelligent and that means there is a series of new questions that we all have to wrestle with. Essentially, we need to understand it and we need to prepare for it. Preparing for it is everything from how we make changes in our education system to changes in our law and policy.

What’s notable to me is how it cuts across so many different areas. Take the idea of face recognition. It’s an issue for the DC police and federal government and US military but it’s also an issue for pretty much every business. Kentucky Fried Chicken is talking about applying face recognition! Okay, so what does that mean? What aspects of it are we okay with and what aspects are we not okay with? So I hope the book, by giving people an ability to visualize this future world, equips them better to navigate it as it all becomes real.

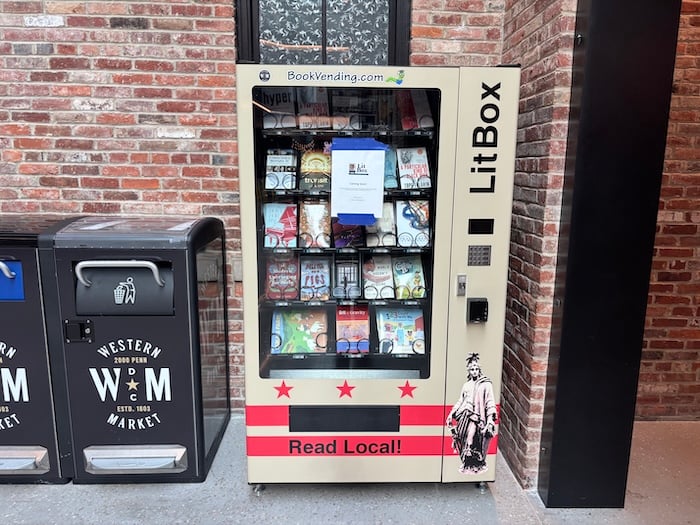

One thing I should add is how the pandemic has accelerated everything that was in play. All of the issues of Burn-In were in motion before the pandemic. But all the data shows that they’ve been drastically accelerated by it. Our opening scene has a futuristic delivery robot driving down the sidewalk, and that very system has been deployed to deliver groceries in [parts of DC]. Or one of the characters is doing remote work, but at a cost to his marriage—something a lot of people are dealing with. Much of the population has been thrown into remote learning and remote work to a level that was never anticipated. In other sectors we’ve been moved forward in a matter of weeks to where we didn’t think we’d be for ten years. Telemedicine is a good example of that. And we’re now putting into place plans for AI tracking of society at whole new levels. When we get through the pandemic, one thing that is easy to predict is that we’re not going 100 percent back. And so that means also that all the tough social, policy, legal, moral, security, and even family issues that our characters experience, they’re also going to come faster in the real world.

There’s a fault line at the center of the book between people who are excited about technology and people who are distrustful of it. Where do you fall?

Technology is a tool, and every tool has been used for both and good and ill. The very first stone that was picked up was either used to smash up some food or bash someone in the head. Today, drones have been used for war and they’re also being used by human rights organizations to detect and stop war crimes. In Burn-In we play with that duality of these technologies coming. The Washington, DC, of the future will be a smarter city—you’ll have smart homes, smart transportation, the internet of things weaving through buildings that range from government headquarters to restaurants and retail. It’s going to create a level of convenience and money-saving and energy-saving that is very much out of the most utopian views of science fiction. It’s going to be incredible in so many different ways. But, oh, by the way, it will also introduce new vulnerabilities that bad guys might take advantage of to carry out new kinds of crimes. So that duality is always there. It’s up to us to determine which path wins out.