In a publishing market saturated with books about President Trump, a scathing new release by his niece Mary Trump has broken out as a smash bestseller—in part because the Trumps tried to stop its release, and in part because it offers something novel: a professional psychologist drawing on personal experience to paint a family portrait and explain the presidential psyche.

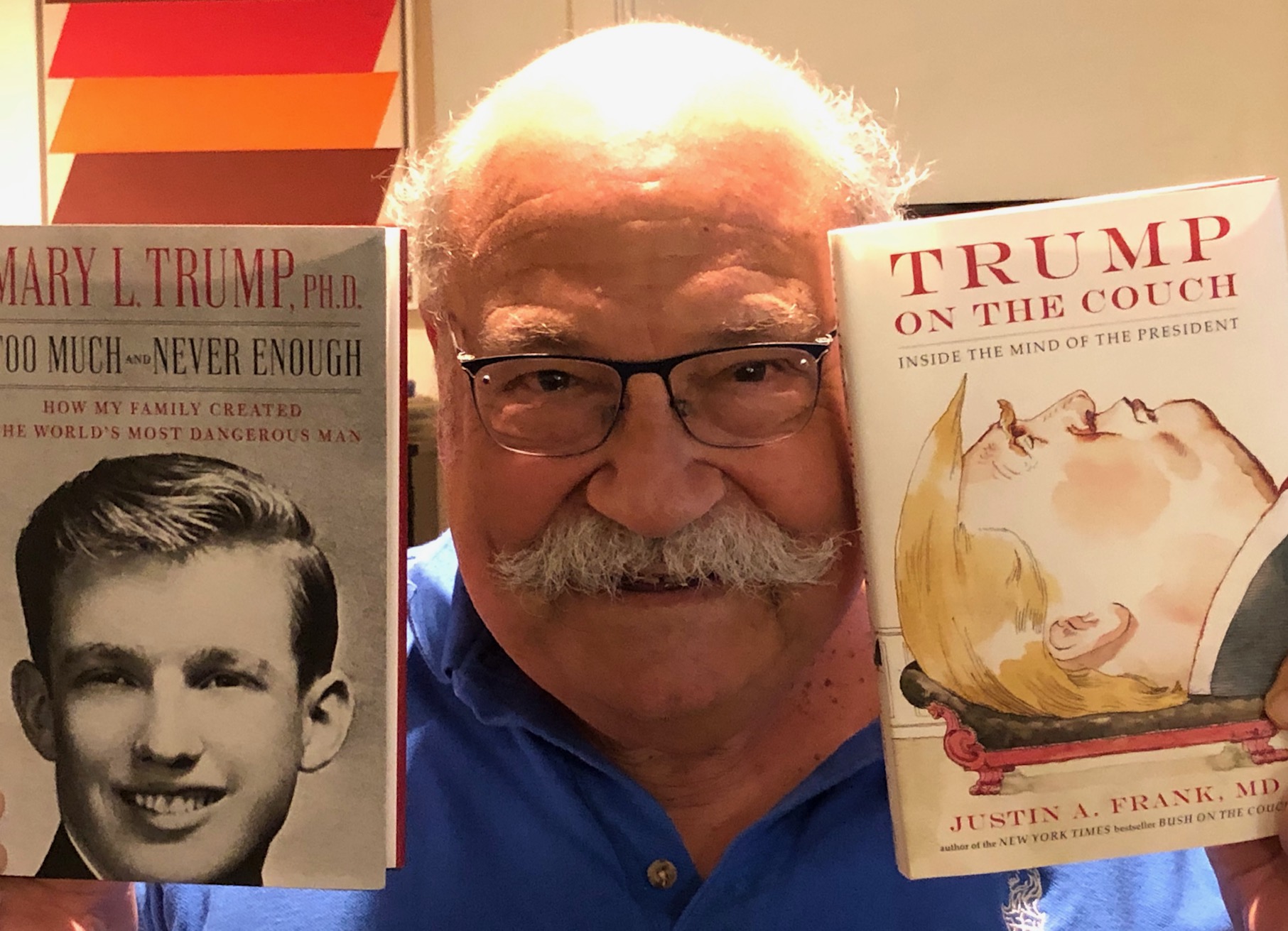

One particularly interested reader: DC psychiatrist Justin Frank, author of 2018’s Trump on the Couch. Unlike Mary Trump, Frank has never met the president. Rather, he based his book, like his previous Bush on the Couch and Obama on the Couch, on a controversial technique called applied psychoanalysis, which involves close readings of biographies, speeches, and interviews in order to come up with a theory of the patient.

So how did it feel reading a fellow shrink who’s had actual experience with the unwitting analysand and his messy family? “I thought it was brilliant,” Frank says. “I thought it was beautifully written. She has a great sense of humor and she’s perceptive.”

More to the point, he says, he didn’t come away kicking himself over having missed something. “It essentially validated the study of applied psychoanalysis because there was not one surprise in it in terms of Trump’s psychodynamics. Everything she wrote about, I had already written about.”

Frank, who attributed parts of Trump’s makeup to having grown up with a distant, cold mother, says some of the new book’s details deepened his understanding, notably the impact of her health problems. “I learned that she was more sickly than I thought after her surgeries,” Frank says. “[Mary Trump] thinks he had a very good attachment to her in the first two years of his life, and the loss was very sudden and traumatic.”

As for the tyrannical Fred Trump, the main focus of Mary Trump’s book, Frank says he knew young Donald was terrified of his father, but was struck by the cruelty of later scenes making fun of the aging patriarch’s senility.

“I’ve written he has an inner conflict between being a builder and being a destroyer,” he says. “And that his destroyer part of his personality has won out, basically, and still is winning now, with how he’s dealing with Covid, how he’s attacking Dr. Fauci. He is hell bent on doing that, unconsciously, which is really about destroying everything his father built, and unconsciously it’s about destroying America in terms of its symbolic element for him, which is about the concept of a founding father.”

He also reveled in Mary Trump’s anecdote alleging that the future president paid someone to take his standardized tests. “She wrote about an undiagnosed learning disability, which no one had ever written about before. I figured it out from my research and wrote about a whole chapter about that in my book,” which touched on shame and lying—perhaps including lying about just who took an SAT—to cover it up.

Mary Trump’s expertise, presumably, will end with her uncle’s administration. On the other hand, Frank, 77 and still a practicing psychoanalyst in DC’s Palisades neighborhood, has a book franchise that can grow every time the White House gets a new occupant. Would he be keen on putting Joe Biden on his virtual couch? He says Biden’s tragic family history would make for interesting work.

“I would start writing about him with my two preconceptions,” he says, “and I would try to not let that dominate the work. My first is I have not gotten over Anita Hill,” who accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment and was raked over the coals by Biden’s committee during the confirmation hearings. “But the other side is this idea that sorrow is the vitamin of growth.”

It’s unlikely that Frank will have professional competition for that book. Under the “Goldwater Rule,” adopted after a number of psychiatrists essentially declared the 1964 GOP presidential nominee as nuts, the American Psychiatric Association forbids members from diagnosing people they haven’t seen as patients. Frank faces no such constraints: He left the association right around the time he published the first of his president-on-the-couch books. Today, he thinks the Goldwater Rule ought to be scrapped.