About Coronavirus 2020

Washingtonian is keeping you up to date on the coronavirus around DC.

States that have reopened bars and indoor dining have higher rates of coronavirus transmission that those that haven’t. That’s according to a new analysis from the the Center for American Progress that identifies indoor dining as a key activity in contributing to Covid-19 spread.

Topher Spiro, CAP’s vice president for health policy, says Michigan and Rhode Island are both good case studies that show the individual impact of indoor dining. Both states had low rates of transmission, but once indoor dining was opened, those rates began to shoot up. When Michigan closed indoor dining and bars again, its transmission rates began to decrease.

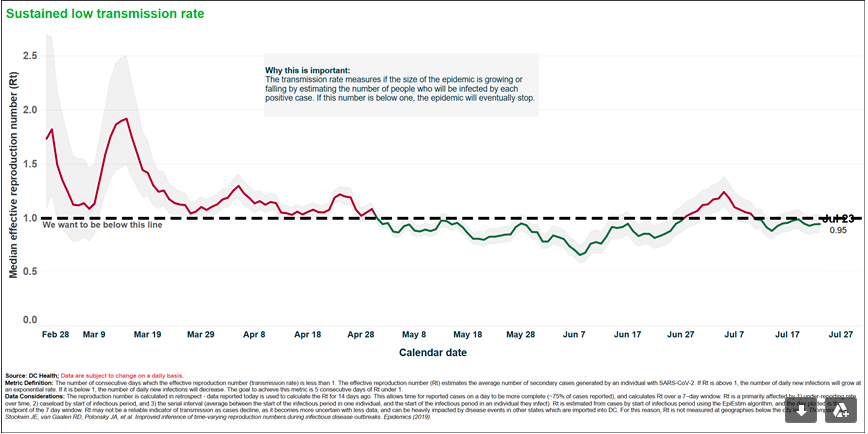

The District’s transmission rates have followed a similar pattern, Spiro says. Prior to the beginning of Phase 2 on June 22, DC’s transmission rate was hovering around a controlled 0.8 (1 is the target threshold). By early July, that number had spiked to close to 1.3, roughly as high as it was in late March and early April.

While a number of other indoor activities opened in Phase 2, indoor dining presents a unique risk in contributing to disease spread, Spiro says. Covid-19 can be transmitted through large droplets (which come out of your mouth when you talk, cough, or sneeze) as well as through tiny droplets called aerosols that remain in the air and accumulate over time. The lack of ventilation in indoor activities creates a higher potential for infection through aerosols, and the nature of dining, which requires mask removal, increases the risk of large droplet spread and infection through aerosols. Though diners in many areas are required to wear masks when not in the act of eating or drinking, Spiro says that’s hard to enforce.

DC officials have said they’ll consider a rollback of indoor dining if the coronavirus situation worsens in the District. But even though a growing number of positive cases dined at restaurants while infectious, Mayor Bowser and DC Department of Health Director LaQuandra Nesbitt have repeatedly said officials are unable to determine whether any one activity disproportionately contributes to the spread of the virus in DC. If they’re able to do so, they’ve said, they would take appropriate measures.

Spiro isn’t convinced by their thinking. “I think it’s hard to say we don’t have [sufficient] evidence of transmission from indoor dining, when we know that contact tracing has not been effective,” he says. Overwhelmed labs are often taking over a week to return Covid test results, and currently only four percent of new DC Covid cases can be traced back to another positive case. “Relying on the absence of evidence from contact tracing is risky. … Given what we know about how the virus spreads, we know enough, particularly in light of the precautionary principle, where you become cautious in the face of uncertainty.”

The economic incentives of keeping indoor dining are obvious. The restaurant industry made up 8 percent of DC’s job market in 2019, and brought in roughly $4.4 billion in sales in 2018. With experts estimating roughly a third of US restaurants will have to close permanently this year, it’s clear how important dining is to DC’s economy.

But it’s possible that keeping indoor dining open could actually do more economic harm than good. If indoor dining reopens too soon, says health economist Emily Gee, localities risk a second wave of closures of restaurants and other businesses. And both Gee and Spiro stress that school closures create a widespread economic impact on working parents.

“I recognize that there’s a lot of pressure for these businesses to reopen, because they’re entrepreneurs trying to make a living, they’re workers who need income to support their families,” Gee says. But “it’s a little shortsighted to say that if we reopen things then the economy gets back to normal. … To restart the economy, you need it to be safe, for people to feel safe venturing out to restaurants.”

Both Gee and Spiro agree that the brunt of the economic pain shouldn’t be borne by restaurants alone, though. The analysis recommends that the federal government offer financial support to bars and restaurants, both through “robust” unemployment insurance and by helping to cover fixed costs during closures or capacity restrictions.