On the morning of March 30, Julia Solomon walked into George Washington University Hospital, rode the elevator up to the ICU, and checked the nurses’ board to see her patient assignments for the day. The previous couple of weeks had been brutal. Every day, the ICU was growing more crowded with Covid-19 patients. Some had already died; many more eventually would. Solomon had become accustomed to looking after patients tethered to ventilators, to watching their lungs deteriorate, and then, when there was nothing left to try, to sharing the awful news with their loved ones.

Solomon had first noticed Francis Wilson a few days earlier. Unlike most of the other patients, he was only 29 years old and he didn’t suffer from any of the chronic conditions that doctors typically found in their worst Covid cases. Yet he’d been hustled into GW from another hospital that had proved unable to help him, so seemingly close to death that a chaplain had already said a final prayer over his body.

During his short time at GW, though, Wilson had made a dramatic recovery. Now, after spending nine days in a coma, he was coming out of it.

Solomon entered Wilson’s room and introduced herself. “I’m your nurse for today,” she said. “How are you feeling?”

Though Wilson’s sedation meds had mostly worn off, he was still a bit groggy. He asked for some ice chips to suck on. “I’m so lucky,” he said. “I can talk. I can breathe.”

Solomon had yet to care for a Covid patient who’d been put into a coma and lived through the ordeal. She wondered what he might remember. “What was it like?” she asked.

As Wilson began to recount his experience, he was surprised by the chilling details he was able to recall. “I fully believed I was dead,” he says. “That this was what death was like.” Today, four months after leaving the hospital, Wilson has mostly recovered. But the memories of his time in a coma still haunt him.

It began in early March, with a tingle in the back of his throat. Wilson started coughing, his head began to throb, and chills rippled through his body. He called in sick to his job in the general counsel’s office at the Institute for Defense Analyses, a federally funded think tank in Alexandria. But he saw no cause for alarm. He hadn’t traveled abroad recently or been exposed to anyone known to have the virus. He figured he was just rundown from his hectic schedule—a full-time job, law school at night, a busy social life. He’d probably picked up the flu.

Soon, though, Wilson noticed a tightness in his chest, and he went to urgent care for a coronavirus test. Over the next few days, as he waited for the results, his lungs began to fail. When he stood up, he’d lose his breath. Sometimes he’d wake in the middle of the night struggling for air. At one point, he made the several-block walk to 7-Eleven for some Gatorade but had to stop three times along the way. Finally, on March 19, following nine days of being sick, Wilson called an ambulance. After he arrived at Virginia Hospital Center in Arlington, the results from his test came back. He was positive for Covid-19.

That night, Dr. Nancy Maaty was starting her shift in the hospital’s ICU when she received the call about Wilson. She walked into his room and was struck to find a twentysomething with dark eyes and a jet-black beard. “We had been hearing reports about patients who are older, with multiple chronic co-morbidities,” she says, “but here we have this really young guy with really not any medical problems.”

Wilson’s forehead was damp with cold beads of sweat, his breathing hurried and strained. More worrying still, he was requiring larger and larger amounts of supplemental oxygen. This was an ominous development—indicating that the virus had already busted through his immune system, weaseled down his windpipe, and begun attacking his lungs. At this rate, it threatened to choke off the flow of oxygen to his brain and kill him. She had to stop it. But how?

I think the best course of action is to put you on a ventilator, Maaty announced.

The device, she explained, would push air through Wilson’s lungs mechanically, allowing him to redirect his energy toward fighting the virus. It was a precautionary measure, a way to buy time in hopes that his body could rebound. But she would have to sedate him and put him into a medically induced coma. He would be unconscious for days. And because additional delays might cause further damage to his lungs, she wanted to get started right away.

He was so close to death that a chaplain had already said a final prayer over his body.

Wilson called his parents in Woodbridge to talk it over. “I thought, ‘Oh, no,’ ” says Anna Wilson, his mother—but what choice did they have? Everyone agreed: It would be best to follow the doctor’s recommendation.

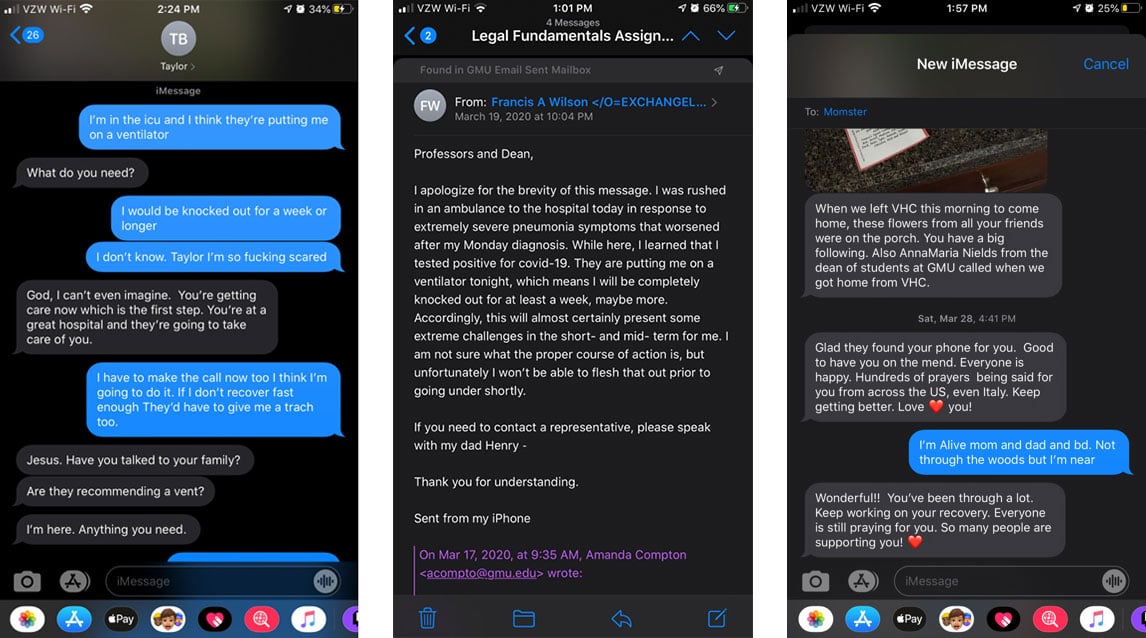

With less than 30 minutes to prepare, Wilson turned to arranging his affairs. “I apologize for the brevity of this message,” he wrote to his professors at George Mason law school, announcing his Covid diagnosis. “They are putting me on a ventilator tonight, which means I will be completely knocked out for at least a week, maybe more. Accordingly, this will almost certainly present some extreme challenges in the short- and mid-term for me. I am not sure what the proper course of action is, but unfortunately I won’t be able to flesh that out prior to going under shortly.”

He then called his boss to discuss going on short-term disability. He asked his sister to keep his friends apprised of his condition, and he reached out to his ex-girlfriend to see if she could swing by his apartment in Arlington to feed his hedgehog and his snake. His mind fixated on the mundane—had he remembered to pay the rent?—as if he were about to leave town for a week of vacation.

When he was on the phone with his parents, they reassured each other. After all, the coma was just precautionary. A few days on the ventilator, he said, and he’d be on the path to recovery: “I’ll see you on the other side.”

After Maaty sedated him, she opened Wilson’s mouth, tilted his head back, and inserted the clear plastic ventilator tube past his vocal cords into his trachea. Mechanical ventilation is instinctually uncomfortable—your body wants to fight it off. So Maaty also used a paralytic agent on Wilson, meant to block his lungs from counteracting the machine.

Once he was connected, Wilson appeared to be in a deep, peaceful sleep. The only sound in the room was the ventilator, hissing air in and out of his lungs.

Pffffff, thump-thump.

Pffffff, thump-thump.

Maaty slipped out to continue her rounds.

Like Wilson, Maaty had grown up in Northern Virginia. She’d completed her medical training at GW Hospital and chosen ICU work because she wanted to care for patients during the toughest times of their lives. Suddenly, at 35, she was entering what might become the toughest episode of her career, and it felt freighted with uncertainty. Her thoughts kept returning to Wilson. If the virus could send a perfectly healthy 29-year-old to the ICU, maybe it was even more unpredictable than doctors believed?

When she got home that night, she canceled her plans to visit her mother for her birthday. Over the next few days, she talked at length with her husband about how best to protect their two children—an infant and a three-year-old—from the risk of infection. “I was terrified for my daughters,” she says. “Francis being young made me start questioning if even younger patients [and] children could get this critically ill.”

She became even more meticulous about making sure nothing that might have been exposed to the virus at the hospital ever entered their home. She starting wearing a scrub cap over her hair in the ICU, she stored additional eyeglasses and hair ties in her locker, and instead of continuing to bring her breast pump in and out of the hospital, she stopped nursing her infant altogether. “I am embarrassed to admit, [but] little of this was based on any science,” she says. “[It was] mostly a reaction to fear fed by the flurry of information coming in from all different sources.” Maaty also checked that her husband was the beneficiary of her financial accounts in case, God forbid, she got seriously sick, too.

For Wilson’s mother, Anna, waiting for news from the hospital became increasingly unbearable. She tried to keep her mind occupied by sending daily updates on Francis’s condition to their large network of family and friends. When the anxiety became too much, she would head to a neighborhood church and kneel alone in a pew, silently stroking her rosary. Before returning home, she would move toward the altar and light a candle. “That gave me some peace,” she says. “Well, I don’t know if you’d want to call it peace. But it gave me hope.”

As his mind became addled by the drugs, he drifted into an intense dream.

Wilson tracked a modest course toward recovery throughout the first several days. His oxygen levels stabilized, and his other organs continued to function normally. “Just got a call from the doctor,” Anna said in a text to his sister on March 23, four days into his coma. “He is improving. Still on ventilator but lowering the intensity . . . Overall we feel confident.”

Still, there were complications. For reasons that are not entirely clear, critically ill Covid patients tend not to tolerate the ventilation process well, according to Maaty, and often require additional sedation. At one point, Wilson managed to pull the plastic tube out of his throat. So to prevent him from fighting the ventilator, doctors continued administering high levels of sedatives—narcotics and other powerful drugs. As his mind became addled by the chemicals and the neurological effects of the disease, Wilson drifted into an intense dream.

I was in Virginia Hospital Center, walking through a hallway. I had just been discharged. A man came up to me and offered me a trip to a conference in Wuhan, China. It was all expenses paid, and the plane was taking off right away.

He said, “Would you like to go?”

I said, “Sure.”

When I got to the conference, there was a cocktail party on the rooftop of the hotel. It was a black-tie crowd, and they were smiling and exchanging Champagne toasts. I was wearing a tuxedo. All of the sudden, I heard glass crashing all around me. I looked over and saw that a warship next to the hotel had opened fire on the crowd. But instead of bullets, the guns were firing tiny capsules of biological material.

I was hit in the neck, and I fell. I could feel my spirit float out of my body and drift toward the sky.

From above, I could see that there were bodies all over the roof of the hotel. As I got higher, I saw a purplish light. It had a female’s voice.

“Francis,” it said, “you’ve died.”

After some initial optimism, the updates from the hospital turned unsettling. A few days into Wilson’s coma, the ICU had called to inform Francis’s parents that their son was showing signs of sepsis. Forty-eight hours later, they were told that an x-ray had detected fluid buildup in his lungs, which would mean more time on the ventilator. A day later came news that his oxygen levels had declined. “I began to dislike the phone,” Anna says. “Because it represented the possibility that they might call with really bad news.”

On March 26, the phone rang around 11 am. It was a nurse with an urgent request: “You guys need to come right over here.”

When Anna told her husband the news, he called the nurse back.

“Is he dying?” Henry Wilson asked.

“We can only say,” she replied, “that it is very serious.”

Henry explained that the couple were devout Catholics. Could the hospital summon a priest to perform the sacrament of last rites?

Anna and Henry had experienced this sense of terror before. They’d adopted Francis in Bolivia, where he was born prematurely after his birth mother suffered a ruptured appendix. They still remember the horrifying phone call, the emergency surgery, the fear that the new baby might die. He spent his first several weeks in a hospital incubator. After Anna and Henry brought him home to Washington, where they worked as federal employees, they watched with pride as he was elected student-council president, earned scholarship offers to college, and enrolled in law school on a full ride.

It would take only one pothole to dislodge the tube connecting him to the mobile ventilator keeping him alive.

Now, as the Wilsons dashed to the hospital, a staff chaplain was honoring their request, delivering a final blessing at their son’s bedside.

The pathology of Covid-19 is ruthless and fickle. Stable ICU patients suddenly crash without warning, leaving families heartbroken and physicians confused. Francis Wilson was no different. That morning, his oxygen levels had collapsed and his blood pressure plummeted. In the course of the crisis, though, his doctors decided to insert an additional IV line near his collarbone and tried stabilizing him with blood-pressure medication. When his family arrived, he was clinging to life.

The Wilsons weren’t allowed into the room. So Henry and Anna huddled at Francis’s door with their daughter, Bernadette, peering through a window. Francis lay still, a network of tubes radiating from his body. “His head was slightly turned to me,” Henry recalls. “He looked troubled.”

Eventually, a nurse in full protective gear entered Wilson’s room and held a phone up to his ear. Another staff member handed a cell phone to Bernadette. One by one, the family spoke to him.

“Francis, you need to keep fighting.”

“We miss you. We love you.”

“You can beat this.”

I was still floating above my body in Wuhan. And the voice that had told me I was dead kept talking to me. She said, “You have 30 minutes to tell your loved ones whatever you need to tell them before you go.”

Around this same time, I began hearing my father, my mother, and my sister. They were saying, “We love you, Francis. Keep fighting.”

It was torture. I could hear my family’s voices, and I desperately wanted to talk to them. But I couldn’t respond. I realized I would never see them again, since it would be impossible to make the 7,500-mile trip to Washington before my 30 minutes ran out.

I explained my frustration to the voice, and she spoke to me again. She said, “You can use your time here and help people at this hotel.”

So that’s what I decided to do. I looked down, and some of the rooms in the hotel had this green light emanating from them. And in each of these rooms, there was someone in trouble. I went room to room to help people out however I could. I went into one where a guy was fighting with a woman, and he was about to pull a gun on her. And I talked him out of that—I stopped a murder there. I went into another room and stopped a rape. In a third room, I saw a man who was passed out on the ground, naked. Face down. There were four other guys, and my understanding was they were going to assault him. So I pushed him underneath a bunk bed to hide him. But then they started coming for me. I felt myself being pushed down onto my stomach. Not like a physical push—it was like a force pushing me down.

I was really scared. I knew I couldn’t fend off all of them. But all of the sudden, right before they got to me, I felt myself being pulled from the room.

My 30 minutes was up.

During the effort to steady Wilson’s oxygen levels, the Virginia Hospital Center doctors had blown through every drug, therapy, and device they thought might help. All but one, that is: a life-support technique called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO. Instead of simply improving the oxygenation process in damaged lungs, ECMO machines act as artificial organs that, for a period of time, can perform the lungs’ work for them. The problem was that their hospital didn’t have one. They’d need to move Wilson across the Potomac, to GW, before his lungs gave out.

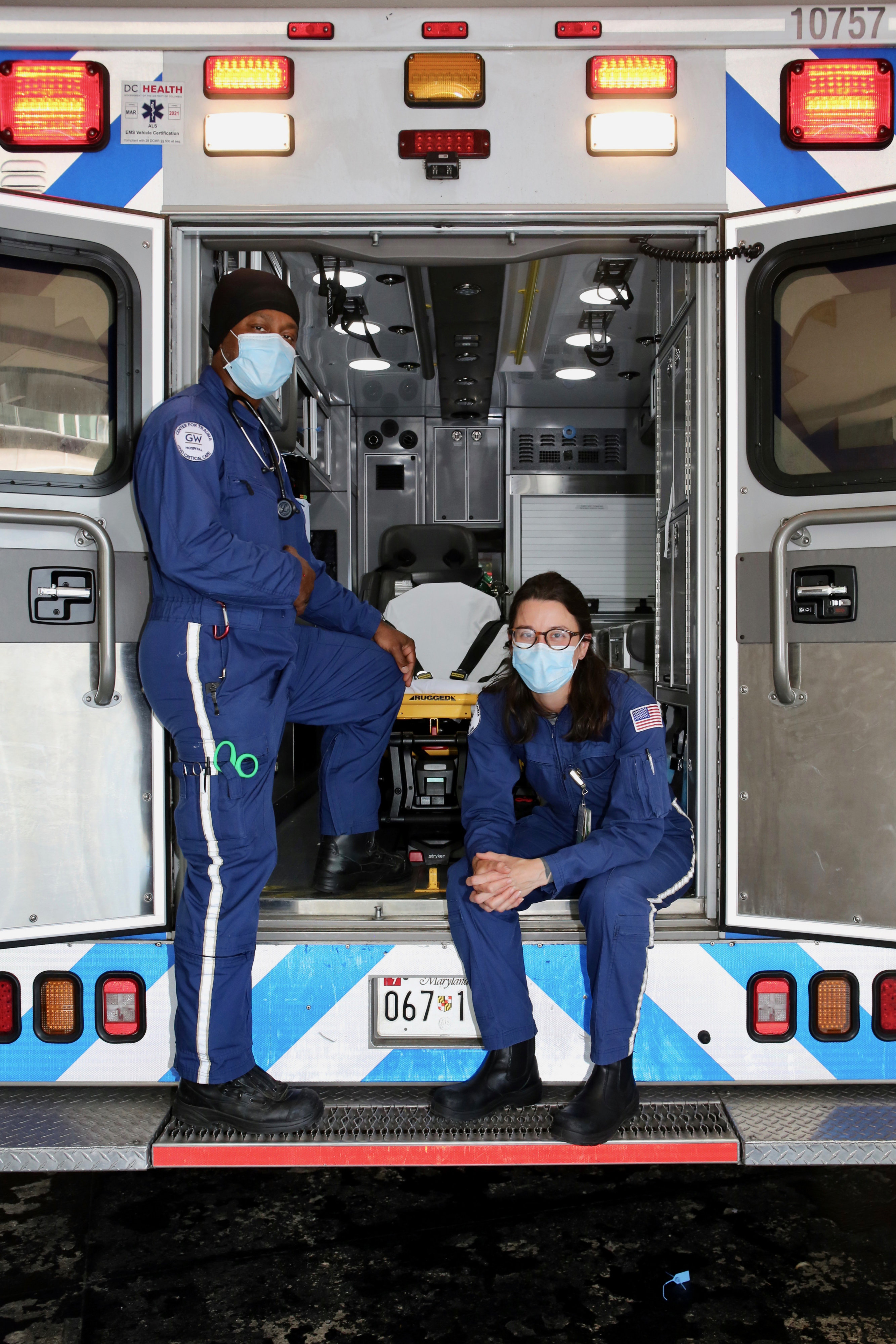

Transporting critically ill patients is a precarious task. Although GW’s special ambulance had many of the resources of an ICU—they call it an “ICU on wheels”—it would take only one pothole, or boneheaded driver, to dislodge the tube connecting Wilson to the mobile ventilator that was keeping him alive. A nurse named Rebecca Chinworth was put in charge of the move. Rushing to Wilson’s room with a stretcher, she spoke briefly with his family—“I literally could see the fear in their eyes,” she remembers. She promised she’d do everything she could.

As the ambulance bolted back to DC, sirens wailing, Chinworth hovered over Wilson in the back. “I am checking literally everything, rechecking everything as soon as I finish checking it,” she says. “Because the difference between a centimeter can be the difference between my tube coming out and this guy having an airway.”

When they pulled into GW about ten minutes later, Wilson was still stable. A team of six doctors and nurses hoisted him onto an ICU bed and got to work.

After I escaped from the attackers, I was reabsorbed into my body, lying down on the ground floor of the hotel. At that point, I became completely paralyzed. I was aware of everything going on around me, but I couldn’t move or speak. There was no question in my mind I was dead.

I noticed that I was being moved along a conveyor belt through the bowels of the hotel. It seemed like I was traveling for hours. Eventually, I got to some sort of processing plant. It was massive—thousands of bodies were being pulled toward a central terminal, and there were lights flashing. Green meant you were dead; yellow meant you needed more testing. When I got to the terminal, I looked up at the light. It flashed green.

The conveyor belt brought me outside the hotel, to a pasture on a mountainside where bodies were being buried. I was thrown into a tomb and covered with dirt. I was paralyzed and alone at the bottom of a grave, and I suddenly lost the ability to breathe. I could feel the oxygen seeping out of my body. It was absolute terror.

Out of nowhere, I was pulled out of the tomb and deposited in a large circular room. There was a group of men attacking the dead bodies. I realized that I was no longer paralyzed, so I began frantically waving my hand, signaling for help. That’s when I heard a man’s voice calling to me. He said, “Dude. Chill out. You’re at George Washington Hospital.”

And everything went blank again.

Danielle Davison, an ICU physician at GW, decided that her first step was to flip Wilson onto his stomach. Known as “proning,” the maneuver has proved effective at increasing the lung function in seriously sick Covid patients. But at the last moment, Davison changed her mind, opting to hold off until they could run some labs. She wanted to see Wilson’s blood-oxygen levels. The results would take only a few minutes.

As it turned out, Wilson’s oxygen levels were substantially better than expected. He didn’t need to be proned, Davison realized. In fact, he wouldn’t even require ECMO. It was an unexpected, remarkable turnaround, in a mere matter of hours—one that served only to underscore the unpredictable nature of the disease: Coronavirus symptoms can improve as dramatically as they come on. “His body was fighting the virus, and the inflammation was subsiding,” Davison says. “It was his time.”

Over the next several hours, the doctors and nurses watched as Wilson’s breathing function improved. His oxygen levels got better, and his blood pressure stabilized. Within a day and a half, they were able to begin weaning him off sedation.

Sometime on March 28, Wilson drifted back into consciousness. His mind was still swimmy from his nine days in a coma, and he was confused to find that he’d been strapped to his bed. (He’d been flailing his arms.) “You gave us a scare,” a nurse told him. “You were right there on the edge.”

Wilson couldn’t talk—he still had the plastic tube in his throat—so he used a pen and paper to ask the nurse for his phone. “I’m alive, Mom and Dad,” he tapped out in a text to his mother. The following day, he posted to his Facebook page. “I have been under for days and thought I died multiple times,” he wrote. “But I made it through.”

“It’s the trauma of dying in the dream, compounded by the trauma of realizing I was that close to death in actuality.”

Bernadette’s boyfriend happened to be scrolling through social media at the time. When he showed Bernadette her brother’s post, she jumped to her feet. “Oh, my God!” she cried.

She grabbed her own phone and noticed there was a new text.

“It’s him!” she shouted. “He’s awake! He’s texting!”

When word of his recovery reached Nancy Maaty and her team back at Virginia Hospital Center, they were elated. Wilson was among their first patients to come off the ventilator after being so close to death. “It was kind of giving us hope,” Maaty says. “It was nice to see that we can make a difference here. That our interventions can help.”

Wilson, though, would soon face a new kind of darkness. When he’d woken up in the ICU at GW, the first harrowing memories of his dream began to percolate: He remembered being paralyzed and alone at the bottom of a grave, feeling consumed by terror, but also regret. “There was still that feeling there was stuff that I still needed to do in life,” he says, “and frustration that I was not able to do that.”

After he was discharged, he felt compelled to reconstruct the full sequence of events—everything that had taken place while he was comatose. He reread the daily updates on his condition that his sister had posted to Facebook, and he studied the text messages he’d sent just before going under. He had lengthy conversations with his family, and he reached out to the doctors and nurses who had cared for him in the ICU. It was only then that he realized just how close to death he’d come. Several nurses told him they’d never seen someone so sick survive Covid. And, bit by bit, he recognized how memories from his time on the other side corresponded to real events that had occurred in the ICU.

Piecing together the timeline inflamed a different type of pain. “It was terrifying in a sense, because up to that point,” he says, “I had told myself it was only a dream.” Wilson had nightmares of being buried alive. He woke up in a panic thinking his IV lines were no longer attached. On another occasion, while he was watching TV, a scene that took place in a graveyard left him overcome. “It’s twofold,” he says. “It’s the trauma of essentially dying in the dream, and then that’s compounded by the trauma of realizing that I was that close to death in actuality.”

Several weeks after leaving the ICU, Wilson discussed his dream with Maaty. While it’s unusual to recall them in such detail, many ICU patients who come off life support do report experiencing vivid and intense dreams while they were under, she says. Wilson’s was likely the result of the drugs used to sedate him as well as the neurological impact of the virus itself. “Not just Covid—every kind of critical illness affects your brain,” she says. “And certainly, critical illnesses that affect your oxygen level will probably have a more profound effect on the brain.”

Wilson’s problems sleeping, meanwhile, sounded like a condition called post-ICU syndrome. Thanks to medical advances, a growing number of patients are surviving critical illnesses that would have killed them in the past. But that means more people are encountering a range of intense symptoms—psychological in some cases, physical in others—when they leave the hospital. “There are veterans who have been in combat, and their stay in the ICU was more traumatic than their experience in combat,” Maaty says.

Now, several months after returning home, Wilson is doing better. His physical health has continued to improve, and the flashbacks have begun to dissipate. After graduating from law school, he started working full-time again, remotely, in May. That same month, he returned to GW and delivered lunch to the ICU staffers who had helped save him.

Though he assigns no religious or spiritual significance to what he experienced, he says he feels changed by it, by the haunting sensation of being dead and buried in an unmarked grave. “It was so vivid and so real that for all intents and purposes it’s what I lived,” he says. “That was my experience. And going forward in life, that is a memory as opposed to a dream.”

This article appears in the August 2020 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)