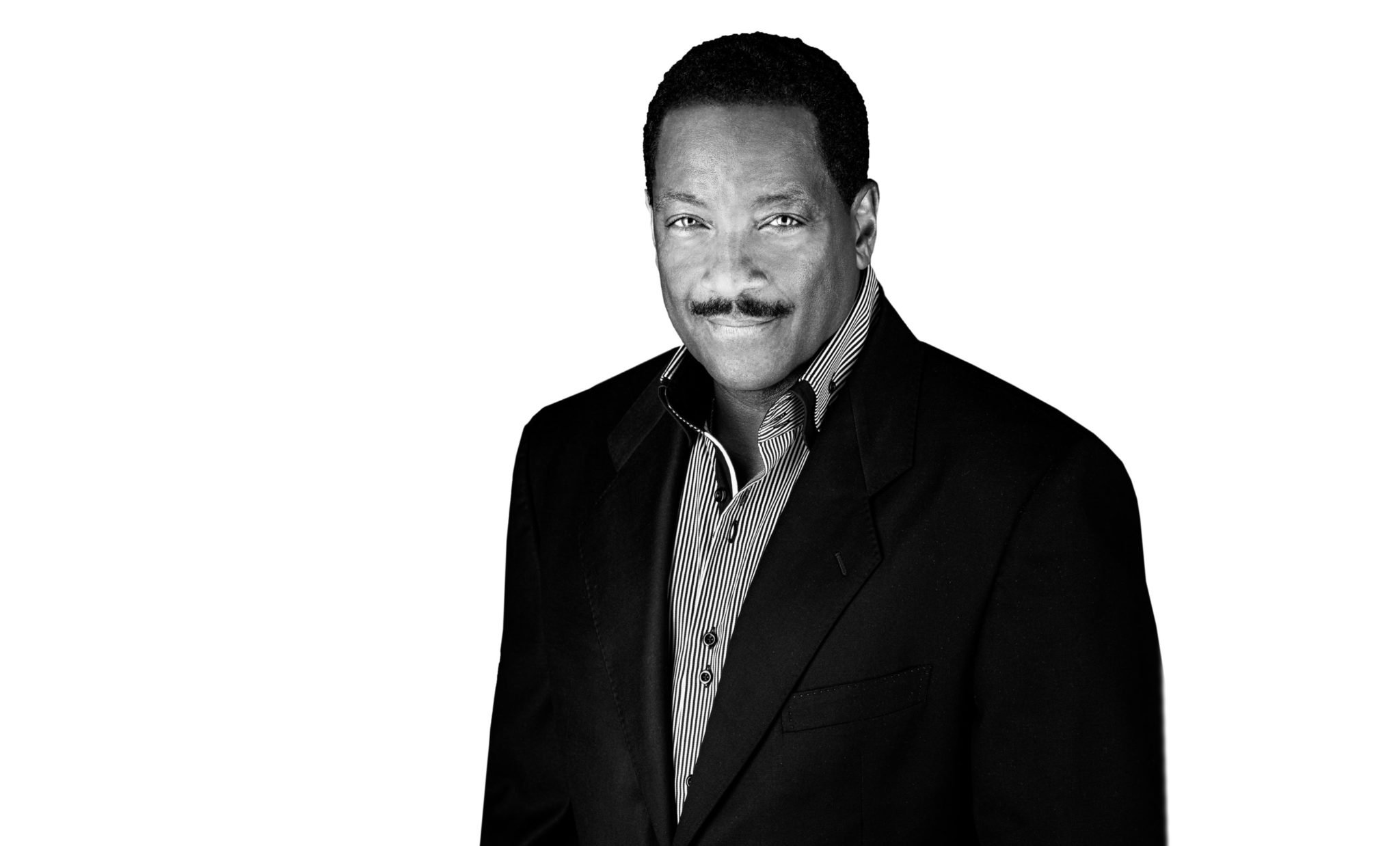

Donnie Simpson is one of Washington’s most vital voices. A smooth-talking fixture on local radio since he rolled into town from Detroit in the late ’70s, he was the creative force behind WKYS, transforming it from a fading disco outpost into an R&B behemoth that became the city’s top radio station. Simpson remained a beloved presence on the airwaves after moving to WPGC and then WMMJ (Majic 102.3), where—more than 50 years into his career—he still spins records and riffs on whatever’s on his mind for four hours every weekday.

On October 29, Simpson will be inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame, an honor that means a lot to him. “When I look at some of the people that are in there—Amos ’n’ Andy, Bing Crosby, Dick Clark, the Lone Ranger—that’s crazy,” he says. “I’m in the Hall of Fame with the Lone Ranger!”

What makes for great radio? How do you create something that people feel connected to rather than just being on in the background?

I spent a lot of years trying to figure that out. I think it comes down to something very simple: that I am me. That’s all I ever am. You get the same person on or off air.

But it’s not just your voice on the air. As an executive and a programmer, you made WKYS the number-one station in DC for a bunch of years. What did you figure out about what our city wants to listen to?

This may answer it by me telling you how I became program director. I had absolutely no interest in programming. But the station was getting killed. And the program director I was working under—I was his music director—we would have music meetings with his two assistants and my two assistants. This is the key moment for me. [He played us] the Rolling Stones’ “Beast of Burden.” He went around the room. “Steve, what do you think?” “Oh, it’s great.” “John, what do you think?” “Ah, it’s fantastic.” “Donnie, what do you think?” “I love it. But we can’t play it.” I said, “You know, it’s basically a Black audience. This doesn’t work for us.” I have played all kinds of music through the years, but it’s got to fit a certain groove or feel or vibe. “Miss You” by the Rolling Stones, absolutely. But not “Beast of Burden.”

Radio has lost its balls. So much of the personality has been stripped from it. I hate that people don’t have freedom to do what they want to do.

Anyway, I think he got frustrated, tired of rejection from me, and asked for my resignation. I gave it to him and didn’t go to work for three days. I was fed up. I was ready to leave. Finally, the general manager calls my house and says, “Donnie, would you have dinner with me tonight?”

So I went, and he wanted to know what was going on. I told him that story [about the Stones song]. I told him that the station was just awful to me. We were in 16th place because we’re playing stuff that people can’t relate to. You know, we’re playing the Little River Band’s “Reminiscing.” I like a lot of this music, but it did not fit.

There wasn’t really a strategic vision for the station.

Yeah, exactly. This program director, he had come from top-40 radio. I get that. But that’s not what this station was. That’s not what the city was. We just kept talking [at the dinner] and he says, “Donnie, would you [write an] outline of all the stuff that we talked about tonight and get it to me tomorrow?” I wish I had it now. It was really the blueprint for a radio station. I talked about community involvement—that the station was so removed from the community. And I talked about music. I even put together a cassette of music and told him why each song was there.

So he looks over this [outline] and he says, “Would you become the program director and implement it?” I had no idea whatsoever that was why he was asking me for this. I was just trying to help. I thought about it for about a minute, and I said, “Sure.”

The two greatest moments that I’ve ever felt in radio—this was second: when I went back to that radio station and went through that rack of music saying, “This is out, this is in. This is out, this is in.” It was the most amazing feeling. And then the station skyrocketed. We went to number one in nine months.

So I tell you all of that and say this: Part of the magic for me is that I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t want to know. I don’t listen to tapes of my radio show. I’m always afraid that I’ll try to figure it out, and I don’t want to figure it out. To me, radio and television are magic. It’s magic. It just exists. I’m afraid that if I start analyzing it, I’ll become analytical. I don’t want to become mechanical. I don’t have to be perfect. I just have to be me.

So now I have to ask what your top moment in radio is.

Oh, wow. The day I left WPGC. [Simpson left in 2010 after almost 17 years at the station.] That was the greatest day of my career. That place was so toxic. Out of my 51 years in radio now, 50 of them have been an incredible joy. That last year there was the worst year of my career. I hated it.

What happened?

They wanted to control my show. I brought in my own records, played what I wanted to play, said what I wanted to say. Now all of a sudden, after all these years, [I] don’t know what [I’m] doing? I just said, “Okay, I’m done.” I retired for five and a half years. I’ve never worked in an environment like that. All my career, people left me alone.

You know, I don’t “employee” well. I don’t like being told what to do. One day, I happened to be in New York, and I went to visit Howard Stern. We’ve been boys for 40 years. We’re sitting there talking, and Howard said, “Man, isn’t it amazing that these people will pay you all this money to do this and then want to tell you how to do it?”

My last day there was the day before my 55th birthday. That’s when I scheduled it. I said, “This drama will not go into my 55th year. I’m done.” When I left that station that day, man, I’m telling you, I got to the car, I reset that button on my dial, and I’ve never heard [the station] since.

When rap first started, man, I’m not proud to say I predicted, ‘Nah, this will be around for about nine months.’ Boy, was I wrong.

What do you miss most about DC radio back in the glory days of the ’70s and ’80s?

Radio has changed. Radio used to be so progressive. Now everybody’s scared: scared to play certain music, scared of losing your job as talent, fear of losing your job as management. Radio has lost its balls. So much of the personality has been stripped from it. I hate that people don’t have freedom to do what they want to do.

One of the biggest moments of my career was in Detroit [before I came to DC]. The guy on before me was my closest friend. He turned me on to Elton John. I’m listening to the song “Bennie and the Jets.” I’m like, man, I love this song. But I was scared to play it because Black audiences didn’t know Elton. Finally one night I decided, I’m playing it. I played it twice that night. I played it the second time because the phone was jumping off the hook from the first time I played it—I mean, the likes of which I have never seen. It was so instant.

The next morning, the morning DJ called and woke me up at 7:30. “What is this song you played last night? ‘Jenny and the Nets’ or something? You got to bring it to me.” I had to get in the car, drive down to the station, take it to him so he could play it. The phones were going crazy.

In two days, Elton called the radio station from London: “What is this I hear, ‘Bennie and the Jets’ is breaking in Detroit?” Six months later, he comes to Detroit, holds a press conference to pre-sent me with a gold record for this thing. He said, “I couldn’t believe it. It was just a tongue-in-cheek song on the album. I didn’t think anything of it.”

My point is that doesn’t happen in 2020. Because a DJ doesn’t have that freedom to just go on and play a song like that. All the music is preprogrammed, it’s all researched. I hate that radio has become that. I still play whatever I want to play, but there are young people out there right now who have a great set of ears who cannot express themselves musically like I was able to.

I remember listening WKYS as a kid back in the ’80s, and then at some point I switched to WDJY. Because, as I remember it, you weren’t really playing rap, and that’s what I most wanted to hear at the time. What was your thinking about hip-hop back then?

[Laughs.] When rap first started, man, I’m not proud to say that I predicted, “Nah, this will be around for about nine months.” Boy, was I wrong. I remember when my eyes were opened. I had gone home to Detroit, and they were just going crazy over Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks.” I was like, wow, look at this. That song just opened it up for me.

You have to be open to music. I’ve never wanted to be the guy that said, “Oh, man, they don’t make music like they used to.” Because that statement is true. They don’t make music like they used to. They never have and they never will. It’s always changing. And if you get stuck, then you won’t change and you’ll be done. It’ll be a wrap for you.

When I talk to friends who are like, “I don’t like rap,” I’ll be like, “So you don’t know the flow of Biggie? Wow, okay. I mean, the brilliance of Jay-Z?” I’m glad that my ears are open to that. I’m always open to what’s new. I love music, period. The greatest compliment that I can get from a listener is “Thanks for broadening my ears.” I get that all the time. I was taught that it’s broadcasting and not narrowcasting.

Have you ever ended up playing “Beast of Burden” after that meeting, just to give it a shot?

No, I’ve never played it. [Laughs.] I’ll listen to it again. I mean, I liked it. I just didn’t feel that it fit.

You’re still on the air every weekday. How demanding is it to do that show?

The only challenge is having it end every day. We have so much fun that when it’s over, we can’t believe it’s over. So no, it’s not a challenge at all, really.

What would it take for you to retire?

If I were an athlete, you could put a stopwatch on me and see if I’ve slowed down. But for what I do, I don’t know. I guess people will let me know. I’m 66 now. I started thinking, well, maybe in four years, at age 70, that would be the time. But if you still are enjoying it . . . .

I have no idea when I’ll know that it’s time. It’s definitely not now. As a matter of fact, I just signed a new two-year deal Monday. So I know I’ll be around. I’m committed to that long, anyway.

Wow, you’ve had a good week. Maybe this week is your number-three career moment.

[Laughs.] Yeah, it has been a good week. This Radio Hall of Fame thing has just been amazing. This is really big to me. Because it is what you do. And I’m also proud because I come in on the shoulders of a lot of very talented Black folks through the years who just were never recognized. So I’m honored and I hope that people who came before me are proud—and that this opens the door for others. There have only been a few talents I think that came from [DC] that have gotten that call.

Melvin Lindsey is not in the Radio Hall of Fame? [Lindsey, a revered figure in DC radio, hosted the original Quiet Storm show at WHUR. He died of AIDS in 1992.]

No. He should be. Melvin was something else. There’s someone who had total freedom to play what he wanted to play, and look what he did. You didn’t even need a radio if you lived in DC at that time. Just walk outside, you’d hear Melvin. I was so proud when I hired him away from HUR [to WKYS in 1985]. That is significant to me because I’ve always tried to help correct pay scales between Black and white talent in this business. And I gave Melvin a morning-show contract: five years, a million dollars. That’s what the top morning shows were getting, that kind of pay. That’s one of my proudest moments. It gave me great pride to pay Melvin that kind of money, and I did because I was in a position to try to help correct those pay scales.

And I would think he was generating a lot of income for the station.

Oh, without doubt. Melvin was a huge success, man. I mean, you want that guy on your team. We had billboards and

bus backs all over the city: “Donnie Simpson and Melvin Lindsey, together at last.” The only problem was that people would steal the bus backs. They had to keep making them. Like, what are you doing with a bus back?

This interview has been edited and condensed.