Like the crowd on the Mall, my emotions at home on the couch January 6 started by seeming small and easy to dismiss, and then came fast and incoherent and intense and overwhelming.

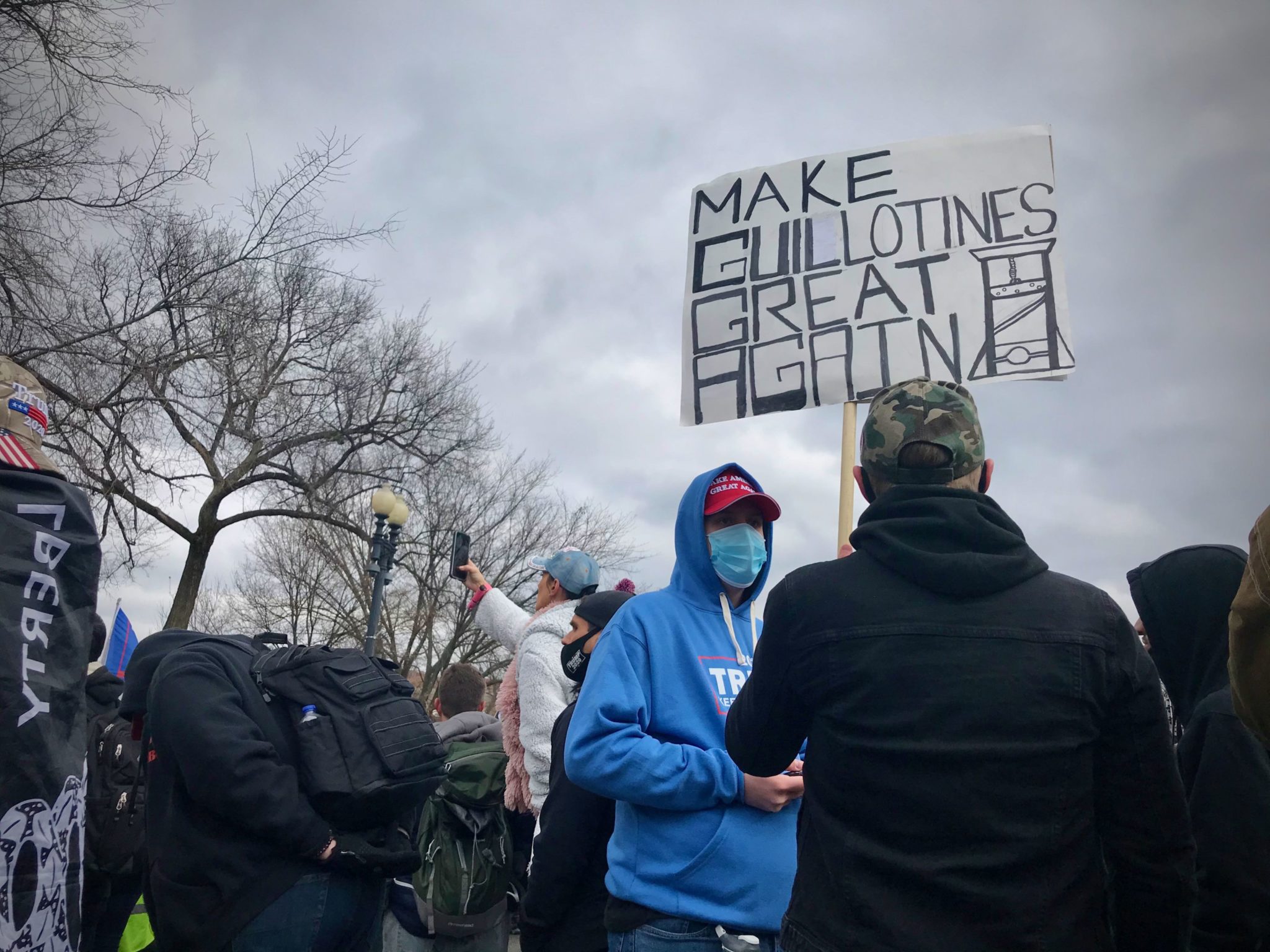

Looking back to the moments before the attack on the Capitol, the feelings moved slowly, predictably. I remember feeling a sadly familiar contempt: At a crowd of people waving signs that touted fantastical conspiracies and glorified improbable sorts of violence. There was disgust: At a president and his entourage riling them up, playing to their lunatic misapprehensions. And eventually, it began to be infused with a certain degree of anxiety: Might these rantings and ravings and empty-seeming evocations of strength actually sway the proceedings in Congress, where so many self-serving legislators were already indulging the falsehoods?

Then it sped up: Shock, disbelief, anger, fear, confusion, fury. There was shame, too, the shame of a country where democratic ideals have always been part of our self-conception, as aspiration if not a reality. And then there was, and still is, grief.

But somewhere in the mix, there was another sentiment, imperceptible in real time. It was something that only became clear later, in the same way that the full horror of the assault on the Capitol emerged only via doomscrolling social media and playing the videos again and again. The feeling was perverse and ignoble: Satisfaction. At last, these people—the unpatriotic president and the hateful storm troopers and the cynical enablers and the spineless cohort along for the ride—had shown themselves for what they were, and done so in a way that no one could ignore.

Oddly, I had imagined a much more deadly scenario. I assumed things would go sideways late in the day, well after the performances on the mall and in front of a well-secured Capitol. Violent rightists went wilding on the streets of Washington after the last pro-Trump rally, and it was easy to imagine it happening again: Someone tears down a sign, someone shouts back at the mob, the weapons-laden militia types escalate, blood flows as confusion reigns—the right blaming antifa, the left blaming Trump, the anxious middle yet again spared having to take sides. But it turned out that the mob actually attacked an institution of American power. Everyone had to take sides. It was about damn time.

I’m not proud of this feeling, which sustained itself even after it became clear that real people had died. It wasn’t simple joy in the fact of Donald Trump’s disgrace, though that was surely part of it. Rather, it was a patriotic sense that finally, finally, the shock of it all might help secure the country. That it might prompt people to appreciate how democracy is fragile, how justice systems are racially unequal, how revanchist white radicalism is a clear and present danger. The institutions of American life, which hadn’t quite seemed up to the task of ensuring the survival of pluralistic society, might yet be firmed up.

In the immediate aftermath of the rampage, a handful of staffers belatedly quit, another handful of political allies even more belatedly broke ranks, and the most egregious of the complicit fellow travelers began to face real consequences. Editorial boards fulminated, political donors closed their wallets, social platforms suspended accounts. Nature was healing.

Now, though, we’re closing in on a week since the shock of January 6, and the emotions are shifting again. Partly, this is because the political system remains unable to handle the task of delivering swift consequence for last week’s acts of violence and betrayal. The 25th Amendment requires bravery. Impeachment requires votes. Hypocritical arguments about how removing the disgraced president would divide the country continue to get press.

But the other thing that has emerged in the days since the attack is that, as it recedes, the incident has come to seem more terrifying, rather than less. Those teeming, furious mobs of Trump flags and crazy costumes and feet on Nancy Pelosi’s desk also contained men with zip-ties who moved with military discipline. The oafs who took selfies on the floor of Congress, it now seems clear, were marching alongside potential killers who dreamt of capturing and executing our elected leaders. The term “riot” seems inadequate. The term “coup” seems less overwrought than it did last week. Rather than a crowd of goons who got lucky thanks to shockingly lax security, we now know of premeditation and hear dark accusations of an inside job.

Which is all to say that the evil that at long last showed itself on January 6 may actually have been comparatively benign—and the real thing still has yet to show itself in a place where people can’t look away.

Maybe, in the end, it won’t. Maybe the shock of January 6, even without the executions and kidnappings of the extremists’ wolfish fantasies, will lead to some new combination of reform and responsibility and decency. I hope so, though I suspect it’ll actually represent a very short pause in the ongoing domestic cold war over truth and democracy and just whose lives count. But amid all the hand-wringing of the past week about the failures of imagination that enabled the assault on the Capitol, we should consider that, even as we assimilate the reality of what happened, our imaginations may still be failing us. Maybe a disappointing return to the January 5 status quo isn’t actually the worst possible outcome. For anyone taking solace in the feeling that the sacking of the United States Capitol represents the final outrage in a process that began with birtherism, it’s worth pondering for just a moment whether it was actually the first shock in a much more catastrophic process that will end with the next Appomattox.