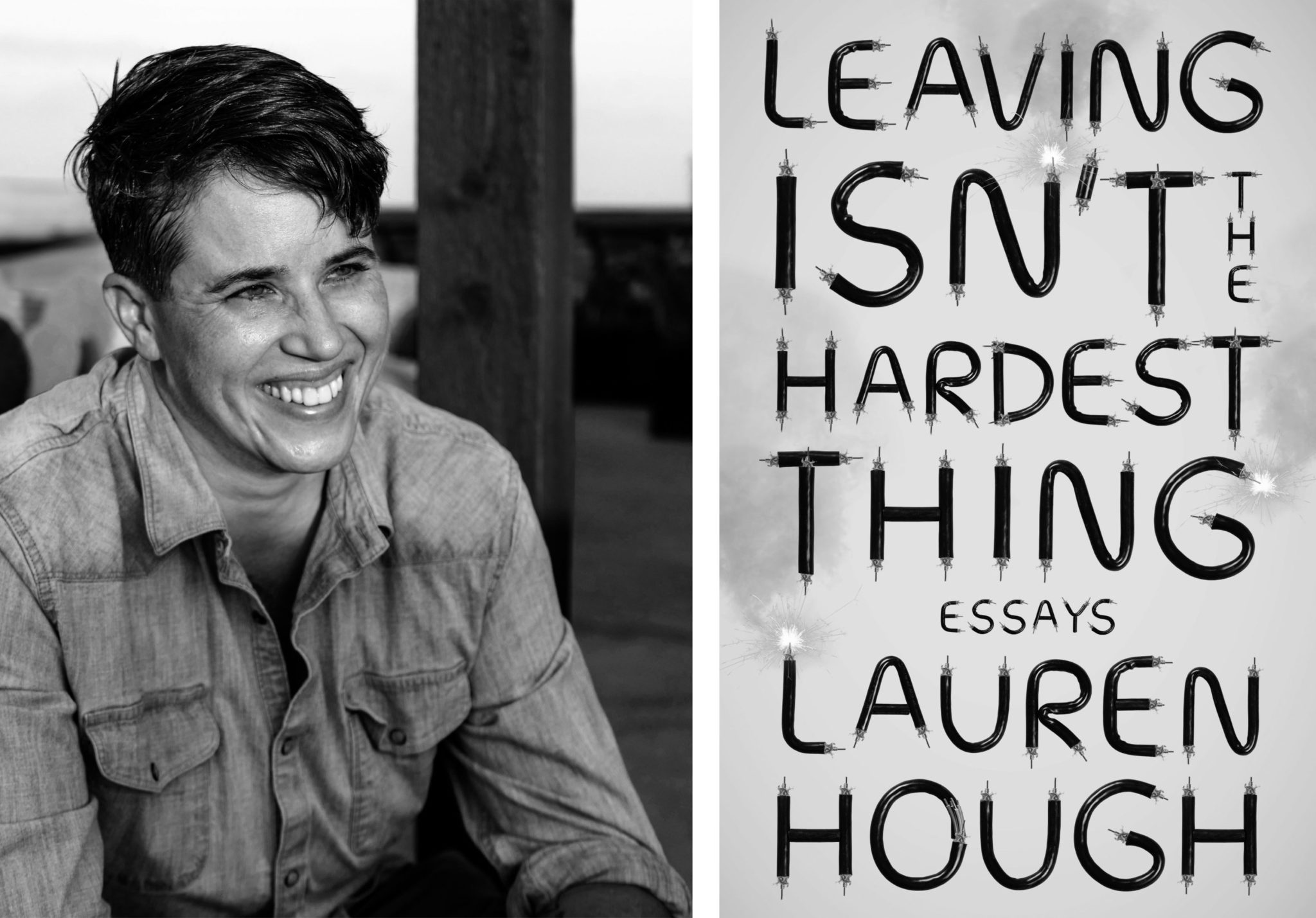

Lauren Hough understands the challenges of escaping an abusive situation. Raised in the notorious sex cult the Children of God—survivors of which include Joaquin Phoenix and Rose McGowan—Hough experienced sexual abuse and violence as a kid. After she managed to get out, she realized, as the title of her new memoir describes, that Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing. Hough first gained attention in 2018 after she published the viral HuffPost essay “I Was a Cable Guy. I Saw the Worst of America” about her time fixing cable for cat hoarders, government contractors, and Dick Cheney in Northern Virginia (it also appears in the book).

In her essay collection, Hough writes about the shocking reality of the cult, and explains how she later navigated getting terrorized in the Air Force for being gay and sleeping many nights in her Ford Aspire around Dupont Circle. She also offers hilarious takes on DC, like when she writes about group houses: “No meat eaters, no vegans, gay-friendly but don’t be obvious about it, down-to-earth, professional, spiritual, no drinkers, no overnight guests without permission from all roommates, no drugs, we have the most insane house parties, quiet and clean, laid back, share cooking, don’t touch my fucking food, no whores, no sluts, no degenerates, no Republicans, no Democrats, no smokers, only outside smokers, 420-friendly, no drama, no atheists, cat-friendly. Cheerful. Upbeat. Positive vibes only.” (We’ve all read that Craigslist ad.)

Hough talked to Washingtonian about fame, DC’s queer scene, and her recent online kerfuffle with reviewers on Goodreads.

Tell me what happened after the cable guy essay was published.

That Sunday [after], my phone wouldn’t stay on—I was getting too many notifications. People started going by [the bar in Austin where I worked] to see me, which was wild. I was talking to editors and agents and producers and still standing outside, in front of the bar, checking IDs, like, hold on real quick. I thought it was a throw away essay. I wrote it ‘cause I needed new glasses and my dog [Teddy] had to go to the vet. I did not expect it to blow up like it did. I think about it as this essay about needing to pee.

But it really resonated. Why do you think it went viral?

There’s a large segment of society that doesn’t realize that the other half has to ask permission to go to the bathroom. Or y’know, have a day off or go to the doctor’s office—in our work lives, we’re not in control of the most basic human functions. We don’t hear very often from people working those shitty jobs because they don’t have time to write. The entire time I had that job, I don’t know that I wrote much of anything. I went home, watched a couple hours of TV, tried to shut off my brain, and go to sleep. It wasn’t until I quit that job that I had time to write about it.

Now you’re including it in this larger collection about your life, from a nomadic upbringing in the Children of God (a.k.a. The Family) to joining the Air Force in the era of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell to working at a beloved DC gay bar. Those all sound like diverging experiences, but in the essay “Badlands,” you actually thread these three together. What sparked that comparison between the cult, the Air Force, and a gay bar?

There’s something that happens in those crappy jobs. You’re all too tired to keep your walls up around your coworkers—you may hate them, but at least they’re not the customers making your lives miserable. At the end of a night, everybody’s pretty raw and way too tired to hold anything back. You get really close. It was a thing that I was looking for in the military and the Family: that camaraderie and friendship and us-versus-them. I didn’t find it until I started working at gay bars where that was my team. These are the people who accepted me and would defend me against anyone or anything just because I was not them, the customer base. It happens in restaurants, it happens in kitchens, it happens in any of those jobs.

I hate the word “family” because I grew up in a cult called the Family. I thought it would be fun to write an essay about how I kind of got to be okay with considering people who are not my immediate family part of my larger family. We do that in cities, though. You move to a city and you have to find your friend group and they kind of become sort of your family—that’s where you go for the holidays, those are the people you lean on when you have surgery and someone needs to walk your dog. A lot of it has to do with being queer. A lot of us are rejected by our families and lose family members, so we’re already seeking a replacement. Historically that’s built into our community.

DC’s queer scene gets a rare spotlight here. You write a bit about the misogyny and sexual assault you faced in queer spaces, too. How did you approach that?

The book itself is a time capsule for the late ‘90s, early 2000s queer life, but I think it was just something I noticed because I come from the military and I’m supposed to be able to walk into a gay bar and feel safe. People go to gay bars to feel safe. It’s bizarre and disheartening that you can also be very unsafe as a woman surrounded by men who are not interested in you sexually, but [have been] trained by our society to still be completely misogynistic. It’s jarring. It’d be nice to feel that there was anywhere safe for women. We had lesbian bars, but I think there are three left in the country, so. It’s a thing we’ve lost. I don’t know that there are safe spaces for women anymore, but at queer bars we’re not, which is disappointing. [Coming] from a cult to West Texas to the military, and then [feeling like] alright, well here’s where I belong—apparently maybe not so much. We’re not exempt from racism and misogyny or any other problem. I think we’d like to be—and we should be, for fuck’s sake—but there’s just as much racism and misogyny among the queer community as anywhere else in this country.

You came to the city some 20 years ago on a bit of a whim. You and a friend were in South Carolina and flipped a coin to decide whether to move to DC or Atlanta, right?

Yeah, it was where we could get on about a tank of gas. It wasn’t as planned as it maybe should’ve been. You don’t really make great decisions when you’re just in survival mode—everything is an emergency and you’re just grasping at anything to keep you from spiraling. The one thing outcasts have always known is you’ll be safer in a city, because that’s where people go. If you’re a queer kid from the middle of Texas you dream of moving to Austin or New York or San Francisco. Those were out of driving distance. So I chose DC: it was close enough, it had a large gay community, I felt like I would be safe there and be able to get a job.

Any regrets?

I’ve not really thought of that. Maybe it was a mistake. [Laughs.] Hard to say. Atlanta’s pretty hot though, it probably would’ve been less comfortable to sleep in my car there.

The memoir frankly details difficult realities in the Washington area, like homelessness, policing, and hunger. It’s a little unexpected given the media attention of the book has focused more on the cult and Cable Guy.

I kinda tricked people there. Surprise! It’s about homelessness and jail. Trying to trick people into reading this socialist manifesto. It’s a strange thing. I was joking about it yesterday: I’m a bestselling author and I’m still prepared to sleep in my car if I need to. I have a camping mat back [there] and a pillow. I’m still preparing for every possible worst case scenario. I don’t know that I’ll ever feel safe completely again—I don’t know that I ever did. It’s a scary thing. In this country, how many of us know exactly how many steps they are from homelessness? What happens when you lose your job? The pandemic’s laid a lot of that bare. They gave us $1,400 once and told us good luck. The people who could work from home, great—everyone else had to risk serious illness or death. Or lose their apartment. We [don’t] have much of a social safety net to prevent that. I still know exactly how many steps I am from that cliff; the cliff is homelessness.

When it first came out in April, some folks reviewed the book on Goodreads. You went on the offensive and tweeted profanity-laced responses to certain ratings, calling these reviewers “fucking nerds” and even blocking some accounts. What happened there?

It was the night before my book came out and I was just terrified. I was joking about something that I thought didn’t matter. It blew up. I had no idea that any of that existed. It’s unfortunate and I screwed up, but I’m just trying to focus on the book now. It’s made the bestseller list a couple times now so I’m hoping I’m past it.

Past what?

Past that affecting the book—I just don’t want it to hurt the book. Like my dumb commentary that had nothing to do with anything. It would be a real fucking shame.

Was your reaction this extreme because the work was so personal?

That’s really where the terror came in of the book coming out at all. It’s a lot of very private stuff people were about to read, so yeah. I couldn’t talk about that because I didn’t even have words for it—I still don’t. I thought I was talking about something that didn’t matter, apparently it does. I don’t know what to say about that. I’m just really hoping it didn’t—I just didn’t want it to hurt the book. There are a lot of conversations in there that I feel need to be had and I think people who have read it might understand a little better, but there’s nothing I can really do about it now.

This interview has been edited and condensed.