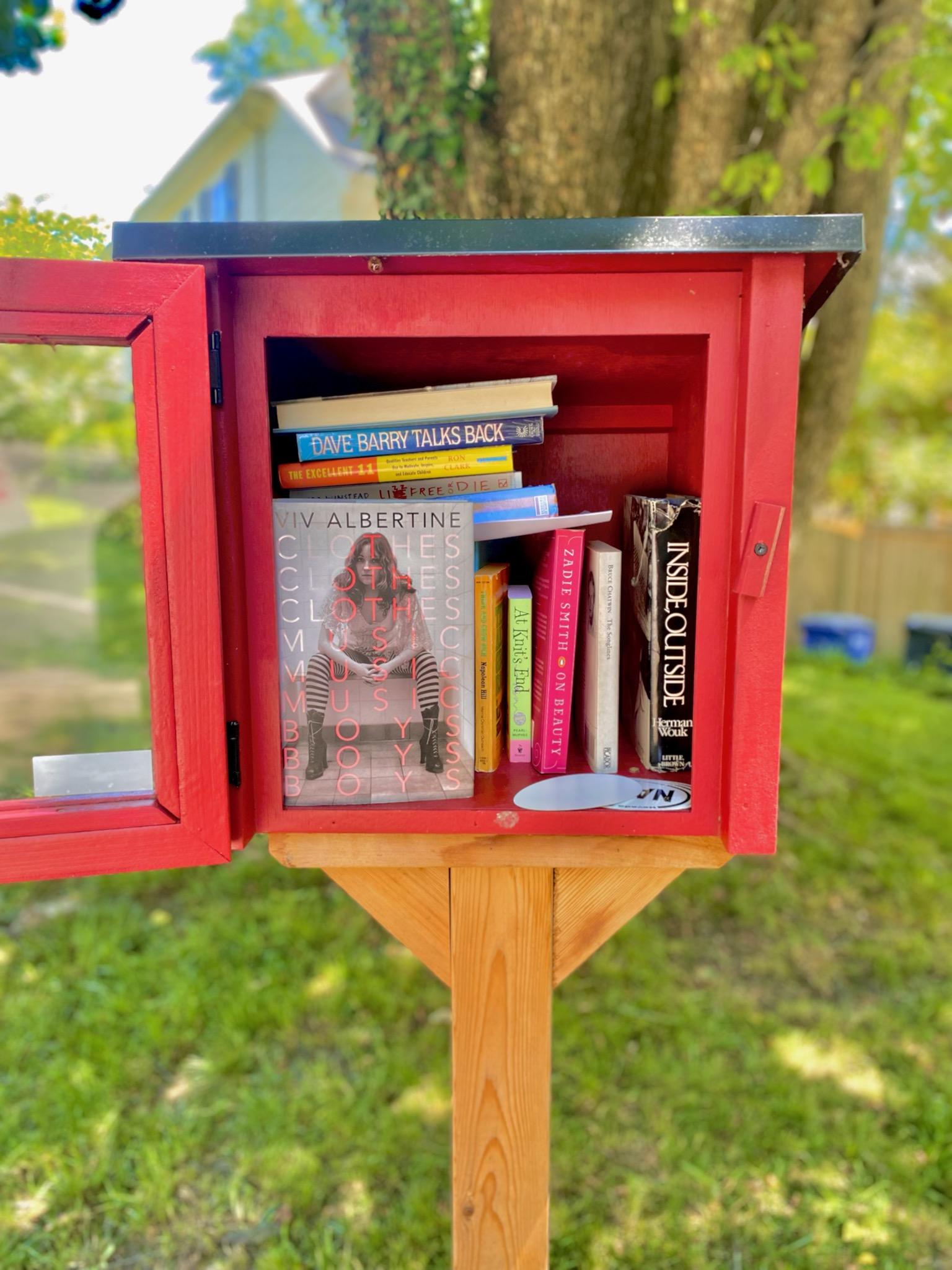

As media empires go, Hunter Bennett’s is fairly modest: a box of giveaway used books and a monthly newsletter. But denizens of Chevy Chase DC with a penchant for punk rock and crime novels will find the Nevada Avenue Outdoor Free Bookshop to be something of a DIY oasis. Bennett, a lawyer and musician (who plays in the band Dot Dash), started the project when he turned 50 and realized he’d never get to reread most of the books on his shelves—so he decided to give some away. The offerings aren’t heavily curated: On a recent afternoon, the collection included books both on-brand (a memoir by Viv Albertine of the Slits) and not (Hillbilly Elegy). The box also contains copies of Bennett’s newsletter, which features Q&As with DC-music luminaries such as Michael Hampton (the Faith, Embrace), Seth Lorinczi (Circus Lupus, Vile Cherubs), and Kim Thompson (Delta 72, Cupid Car Club). One issue had a fascinating conversation with Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, both of whom grew up in Chevy Chase DC and went to Wilson High School. We recently talked to Bennett about how the project came about and where it might be headed.

You aren’t originally from DC. How did you make your way into the music scene, which can be hard to crack for people coming from outside of it?

I first moved here in 1988. I selected the college that I attended [George Washington University] because I liked the punk rock that came from Washington, DC. When I moved down here in August of 1988, I imagined that by September I’d be playing in a band with, like, Ian MacKaye and all the people whose records I loved. But it took a lot longer to get in with the people who I had dreamed of playing with. John Stabb—who was the singer in Government Issue—after they broke up he started this band called Weatherhead, and they couldn’t keep a steady bass player. I answered an ad [for a bass player]. I randomly called and he talked to me for about an hour and a half. That’s just how John was. I scored an audition and I guess I performed well enough that I got the gig.

By day you’re an attorney at a well-known law firm. How does that world jibe with being a punk rock dude?

Well, I think I think it goes together pretty well. Being a lawyer sort of bankrolls my more creative endeavors. I have the complete freedom to put out a free newsletter each month with printing costs and time and labor.

What do your fellow lawyers make of your extracurricular activities?

I’m not sure how many know, but I think those that do think it’s pretty cool. Some of them have written great things for the newsletter, which is really nice of them. At my firm—and I think it’s true of most law firms—people are into some really cool stuff. Because the practice of law is sort of a grueling and stressful one, you’ve got to have hobbies on the side to keep you sane.

So how did you create this very small media empire that you’re now the proprietor of?

I turned 50 last August, and I had an epiphany that I had all these books that realistically I am never going to read again before I die. It seemed to me that I should try and pass them along to people who might also enjoy them. It started with me just putting a table out every couple of months—put “free books” and people would come by. It was a way to meet people. There are a lot of really interesting people in this neighborhood. One guy was like, “I’m into punk-rock books; I’m kind of a punk-rock cult figure.” I’m like, “Oh, yeah? Who are you?” It was Mark Jickling from Half Japanese, who lives a couple blocks up the street. So that was cool.

And then when Covid came around, I thought it made sense to make it more official. I bought one of those prefabricated little libraries. I’m not so handy that I could install it myself, so I bribed a few friends with coffee and donuts and they helped me put it up.

Who did you have in mind as the audience for this thing?

Two groups of people. This neighborhood is sort of regarded as hopelessly suburban and uncool by younger people. They always feel like a little part of them is dying when they have to move up here from, you know, Mount Pleasant or Columbia Heights or somewhere downtown. [Laughs] I want to give them hope that they’re not moving to a place that’s just impossibly lame. Honestly, Chevy Chase DC’s contribution to the culture of Washington, DC, is immeasurable.

It’s fun to live around the corner from the Chevy Chase Community Center, where in the ’80s there were these amazing shows by, like, Rites of Spring, who were truly one of the world’s great bands. There’s this kind of secret history that most people around you don’t even know about.

Yeah. I’m trying to interview [Rites of Spring and Fugazi drummer] Brendan Canty, since he grew up around here. I mean, somebody should do a walking tour of Chevy Chase DC.

So that’s part one of my audience: I want people to realize how cool this neighborhood actually is. And the other group is people my kid’s age—to tell them that there were young people doing great things in this neighborhood 20, 30 years ago, and they could do the same thing. Not necessarily punk-rock-wise, but there are all sorts of cool artistic things they could do.

And then there’s the newsletter, which obviously takes a lot more work.

I often wonder whether I’m sort of blasting this out into the universe and I’m the only person that reads it. [Laughs] I always wanted to have a zine when I was a teenager and in my 20s, but I was really disorganized. The first issue of the newsletter was just a list of the books that I put out, but then I was like, I should give people more content than that. It seemed like a good excuse to contact some old-time DC punk rockers whose music I loved and ask them a bunch of questions.

How are you choosing who to interview?

People tend to interview the same people over and over again. Ian MacKaye is a fascinating interview, and I’ll read or listen to every interview that that he ever does, but I try and hit people that have been interviewed less, or in some cases, not at all.

Where do you plan to take this from here?

I’d love to have a one-year-anniversary party in my yard [this fall], have bands play and have people read. I’d like to have it seem like something other than just a box sticking out of the ground. I’d like it to seem like a real bookstore.

What is your relationship with the Little Free Library system?

It looks like a Little Free Library. To be an official Little Free Library and appear on their map you have to agree to all sorts of onerous terms where if they decide they don’t like your Little Free Library and what it stands for—or you are sullying the good name of Little Free Libraries—they can sort of come after you. I like to think that they would never think that about my Little Free Library, but rather than take the chance I just elected not to sign.

Who could have a problem with crime novels and punk rock?

Yeah, seriously.