On September 26, 2020, Chris Hopkinson crossed the finish line of a nine-day, approximately 200-mile journey, becoming the first person to stand-up paddleboard the entire length of the Chesapeake Bay. Hopkinson’s goal was to make a statement. “Since no one had done it before, I sort of felt like, Okay, I bet if somebody paddleboarded the entire length of the bay, people would pay attention,” he says. And they did. Hopkinson raised over $180,000 for the Oyster Recovery Partnership—enough money to deposit 18 million oysters into the bay, helping to make a dent in an estimated 99 percent depletion of the bay’s oysters.

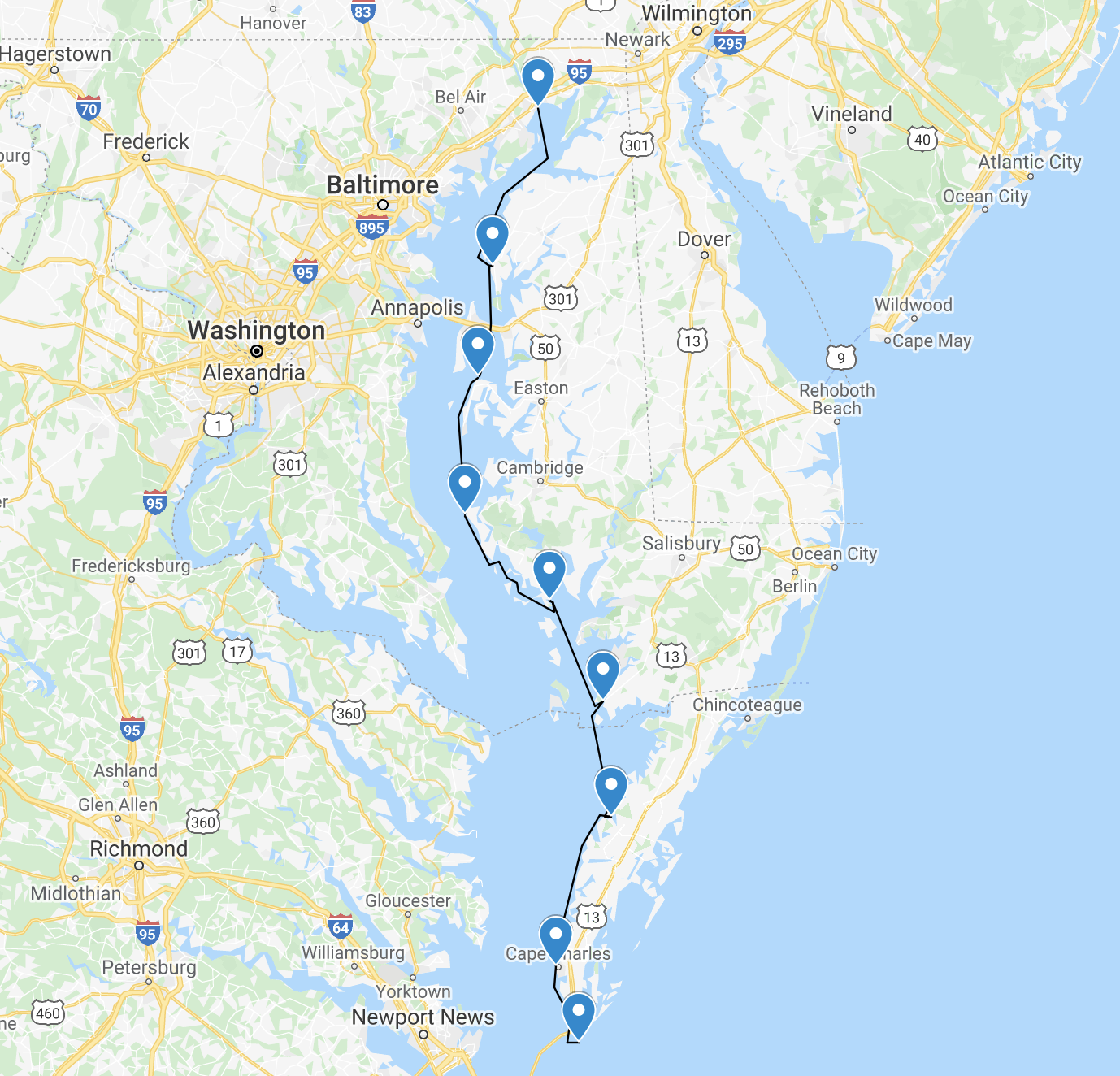

Hopkinson reimagined his solo journey and transformed it into the Bay Paddle, an event he hopes to make annual and which follows the course he traveled along the Eastern Shore. During this year’s race, beginning August 27 from Havre de Grace and ending in Virginia Beach, over 90 people will attempt to travel more than 200 miles, in both relay teams and as individuals, in eight days. Stand-up paddleboards, kayaks, outriggers, canoes, surf skis, and other people-powered water vessels can all be used. “It’s not a competitive race,” Hopkinson says. “It’s really more of a race of determination. The goal is just for everybody to finish.”

Bay Paddle 2021’s goal is to beat last year’s fundraising and plant 200 million oysters in the bay in conjunction with the Oyster Recovery Partnership. Additionally, some funds will be allocated to the Chesapeake Conservancy to aid their efforts to designate the Chesapeake Bay as a National Recreation Area, which would provide more public access to the water and educate people about the bay. Hopkinson wants the 200-mile trek to be recognized by the country, or even the world, as a paddle destination. “Just like the Appalachian Trail, you come out and paddle the entire bay over a couple months or a couple of weekends, or whatever you want to do. And then every year, a group of us are going to do it in an organized fashion to raise money for these organizations.”

Registration is free. A team of military veterans, a team of 30 teachers from Anne Arundel County, and a team of Waterkeepers have already signed up. The event fundraises through sponsorships, such as Red Bull, Old Bay, and Tito’s, as well as through donations made on their website.

Hopkinson won’t be paddling this year; instead, he will focus on ensuring the paddlers are safe and the race goes smoothly.

Connecting With the Bay

Although Hopkinson, 47, grew up in Annapolis, he never had direct access to the Chesapeake Bay until his wife gave him a stand-up paddleboard for Christmas in 2015. After years of craving a deeper connection with the bay, beyond staring out at it from the shore while eating crabs, he finally had a vessel to get him out on the water.

Hopkinson quickly became the guy who paddled down Ego Alley in downtown Annapolis first thing in the morning with one of his kids sitting cross-legged on the front of his board. He never imagined that his three- to four-mile, leisurely outings would turn him into a 200-mile trailblazer.

“Once you get on the water, it’s almost like you’re physically disconnected, but it’s also kind of a mental disconnect, too,” Hopkinson says. “You see all the fish and crabs and the eagles and the herons and the ospreys. And you feel this connection, and then you feel a responsibility to do a better job of taking care of it.”

Hopkinson searched for a tangible way to do something. “We’re trying to save the bay, but it’s really hard to understand what that means or what we’re supposed to do,” Hopkinson says. Then he came across a video posted by the Oyster Recovery Partnership comparing two tanks filled with water and algae from the Severn River, one with oysters and one without. The five-hour time-lapse clearly showed the oysters’ work: cleaning the water by filtering out excess nutrients and sediment, thus transforming it from murky to clear. Hopkinson even recreated the project with his daughter, Olivia, for her 6th grade science project. Now Hopkinson had a goal.

An Ode to the Oyster

According to the Oyster Recovery Partnership, one healthy adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. But the bay’s oyster population is dramatically lower than it has been in the past due to over-harvesting, disease, human population growth, and development around the bay, says Allison Albert Guercio of the Oyster Recovery Partnership. For $10, the Oyster Recovery Partnership can plant 1,000 oysters.

“Chris has an incredible passion and vision,” Albert Guercio says of Hopkinson. “It only takes one passionate person to have a huge impact.”

Since Hopkinson’s 2020 Bay Paddle fundraiser, which was the largest grassroots donation the organization has ever received, Horn Point Lab in Cambridge, Maryland, has been breeding oysters. The Oyster Recovery Partnership will begin to plant the first of the 18 million “spat on shell” oysters this summer in Herring Bay and the Severn River. “Even though that sounds like a ton, it’s still a drop in the bucket of the issue that the bay is facing,” Guercio says. “But any addition is progress.”

Becoming the First

After seeing that oyster video, Hopkins approached the Oyster Recovery Partnership and started to train in September 2017. “I’m not sure that they were 100 percent confident that I would pull it off. And quite frankly, I wasn’t sure either,” he says. “I had people who told me to prepare my concession speech.”

He bought a longer, skinnier raceboard and signed up for a 31-mile paddle race in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in October 2019. He was trying to get an idea as to what it was like to paddle 30 miles a day. In March 2020, he joined Paddle Monster, a service that trains stand-up paddlers, and hired pro-paddler Seychelle Webster as a coach. For 22 weeks, Hopkinson was paddling four days and strength-training two days a week. After three years of training and planning, it was time.

“Nothing went to plan,” Hopkinson says. He mapped out a route down the western shore—the areas where he primarily trained—and planned to pass Baltimore and Annapolis. Then the temperature dropped 25 degrees, the wind picked up 15 knots, and he was forced to reroute to the bay’s eastern shore, just two days before the paddle was set to begin. “From day to day, we almost didn’t know where we were going,” he says.

Prior to his journey, Hopkinson estimates that he spent 120 days on the water. Of those 120 days, he says, he probably fell in the water 10 times. On the first day of his journey, he fell in 15 times. The wind hit him from all sides, the swells were three feet tall, and he couldn’t keep his balance. He was wet and couldn’t dry off or stop shaking because the air was colder than the water. He got hypothermia.

After completing the first leg, Hopkinson got off his board and said to his wife, for the first and only time, “I might be in over my head; this might be too much. There’s no way I can do this for nine straight days.”

The next morning, he looked down at the water, waves swelling below him, as he drove over the Bay Bridge on the way to his next starting point. “The bay looked like the ocean,” he says. “I was incredibly scared for the first time ever to go out in the water.” But he mounted his board and paddled anyway.

No work, no Zoom calls, no news, no social media. For nine days, Hopkinson was completely disconnected. Disconnected from everything but the bay. “I’ve never been more dialed in to anything in my life,” he says. “I was just getting up, getting ready, going paddling, recovering, eating, and doing it again for nine days.”

Hopkinson traveled with the flow of the current, sometimes navigating through nooks and crannies and barely touched parts of the ecosystem. Hugging the shoreline, paddling in shallow water, Hopkinson saw eagles, herons, and ospreys flying above him and fish and crabs swimming below him in the grasses. He stayed on his board most of the time during his seven to eight hours of paddling each day, occasionally sitting down on his board to stretch or eat a protein bar and sometimes stopping on a beach to stretch.

On day nine, less than two miles from the Atlantic Ocean finish line, dolphins approached Hopkinson, swam under his board and breached on the other side, splashing around. He took it as a “congratulations” from nature, he says.

When he crossed the finish line with swollen knees and ankles—friends, family, and bay-recovery supporters cheering him on—he knew it wasn’t the end. Within weeks, Hopkinson was already looking into how to make the Bay Paddle an annual event. How can we turn $180,000 into a million? he thought.