Contents

If you’re of a certain age, it’s easy to remember local gymnast (turned coach) Dominique Dawes crushing gold with the “Magnificent Seven” US team at the ’96 Games. Or, more recently, swimmer Katie Ledecky snagging her first medal in 2012 as a 15-year-old. But who else from Washington has repped Team USA? A handball player turned sales trainer for Nissan, a rhythmic gymnast turned Orangetheory instructor, and plenty of others in our midst whose journeys weren’t always obvious to the eye.

Thomas Hong, 24, Laurel

Sport: Short-track speed skating, 500-meter and 5,000-meter relay

Games: 2018, Pyeongchang

Post-Olympic life: College

“I was born in Seoul. My family emigrated to the US—Howard County—in 2001, and I got into skating pretty soon after, when I was four. It was an activity for my sister and me; it made us feel like we were part of a community. I was national champion in my age group, when I was ten years old, I think. My dad still lives in Korea, so I would visit him in the summers and train there as well.

“I still remember walking to the opening ceremonies with my teammates—we were trying so hard to be in the front of the line to get into the stadium, right behind [luger] Erin Hamlin, who was waving the flag. And the races themselves—I’d never experienced being on the ice and having that deafening crowd noise while I’m racing. It was kind of hard to hear my coaches.

“The 500 meters, I did not qualify for the quarterfinals. Going into the 5,000-meter relay, we were actually the world-record holder. But we ended up fifth overall. My intent was to put myself in a position to go to the 2022 Games. I moved to Salt Lake City in 2019 but didn’t feel like the training environment was working well for me. I finished the season—well, until Covid stopped it. I came home to finish my degree at the University of Maryland. I was pretty excited to get going in my career. Hopefully, I get into medical school this next year.”

Esther Stroy Harper, 67, Camp Springs

Sport: Athletics: 400 meters

Games: 1968, Mexico City

Post-Olympic life: Coaching; real-estate appraising

“I grew up in Northeast DC. I’d only run in the neighborhood. They had a program at the parks department where they took the top 40 athletes to the US Youth Games. I first made the team at age ten or 11. I met Brooks Johnson—he was a coach at St. Albans School, and he told my father he wanted to train me.

“Before the Olympics, we went to a training camp in Los Alamos, New Mexico. I had just turned 15. I got up at 5, did my morning run, then I had to go to school until 3 o’clock. From there, we went to Mexico City. Oh, I went crazy. I wanted to see everything. I wanted to meet all of the athletes. You know, they give you, like, 100 USA pins so you can exchange with all the other countries. I don’t think I came back with anything that said USA. I remember Tommie Smith and John Carlos coming up to the podium [where they did the Black Power salute]. I noticed the black socks, but I wasn’t looking at the hands until they went up in the air. I knew the significance of it because we had gone to different cities, and running all year round, you noticed how we were treated versus how the whites were treated.

“I had actually pulled my hamstring before the US trials, and I was getting treatment the whole time. And I reinjured the same leg in the semis at the Olympics. So I didn’t make it to the finals. I was devastated because I felt really good in the first round and told my coach and my dad that I was going to go all the way.

“I kept training. I ran for Howard University. In 1983, I was coaching at Stanford. My then husband, his job brought us back to DC. I became a real-estate appraiser. I started my own company. Later, I got into college workshops and tutoring. I’ve always continued to run: 5Ks, 10Ks, and then every five years I started running marathons. I run the Marine Corps Marathon every five years, so when I turn 70, I’ll run it again.”

Linda Murray Dragan Kavanaugh, 68, Fairfax

Sport: Kayak (doubles), 500 meters

Games: 1972, Munich; 1976, Montreal; 1980, Moscow boycott

Post-Olympic life: Teaching

“I was a swimmer, and a friend of my dad’s who owned a swim club said, ‘My daughter needs a partner for the Olympics.’ And my dad says, ‘Come on, get in the car.’ I said, ‘Where are we going?’ He says, ‘You’re going to the Olympics.’ That’s a true story. I said, ‘In what?’ He said, ‘You’re gonna kayak.’ I said, ‘What is a kayak?’ Nobody knew what a kayak was back then.

“I must have been 17. We trained at the Washington Canoe Club, down on the Potomac, and in the winter we got use of the Navy’s David Taylor Model Basin in Bethesda. It all happened so fast. And then, of course, the unthinkable happened: terrorists. I was out to dinner with my parents in Munich. We come back [to the Olympic Village] and there’s all these guards. It was like a movie. They paused the Olympics and had a memorial.

“We got to the semifinals. But I’m a little fish in a big pond. I couldn’t move my arms hardly the first race. In 1976, I had a wisdom tooth coming in, and you’re not allowed to even take an aspirin. I was in pain, and it was hard to eat, just miserable. So there kind of went my second chance. Then 1980. We were at a training camp when we heard about [the US boycott]. We had a party, bottles of tequila, and we were just going crazy because it was like your life had just been pulled away from you.

“Every time somebody finds out, they ask, ‘Oh, did you win a medal?’ and I get so mad because, you know, just making the team, that’s a medal in itself. I married a naval officer and moved around with him, raised two children. [My first kayaking partner, Nancy Purves Jones,] is very important in my life. We see each other quite frequently. She lives in Oklahoma. Our family has a river house in Southern Maryland. We have kayaks, and when she comes to visit, of course we have to get in the double kayak and go out.”

Derek Brown, 51, Clinton

Sport: Handball

Games: 1996, Atlanta

Post-Olympic life: School administrator; facilitator/trainer at Nissan

“I was born in DC, raised in Southeast. I went to Gonzaga. That’s where I started my sports career—playing basketball, ran track all four years. I went to La Salle University, and right before I graduated, the men’s national team was on my campus getting ready for the ’96 Games. I became friends with some of them. They invited me to come watch and train. Handball is one of those sports where if you’re a good athlete, you can excel. The coach said, ‘If you want to do this, we’d love to have you on the team.’

“Believe it or not, handball was one of the most attended sports at the Olympics. A lot of people said, ‘Well, I’ve never heard of handball, so I want to see what this is about.’ We had full stadiums. It was such a spectacle and a fast-paced game. And you get to see the athletes because there’s no pads, no helmets, and we’re just running and showing skill. We finished with two wins overall, and that was huge for us. Handball is a European sport—and the European countries, they tend to think that only Europeans can play the game.

“Directly after, I played professionally, one year in Sweden, one year in Iceland. Didn’t go as long as I would have liked. The opportunities kind of dried up, because we weren’t doing a whole lot as the national team. From ’99 to 2002, I was a paralegal. I worked in DC public schools from 2004 till 2012; I was a vice principal one year.

“I do miss it. The athlete and the competitor in me—I just loved every minute that I was on the court. [The US hasn’t] qualified [since ’96]. But the beauty is that in 2028 we’ll have the Olympics on our home turf again, so we won’t have to worry about qualifying. I’ve been taking some refereeing classes. I don’t know if I’ll want to be running up and down the court, but I do want to be involved with handball.”

Steve Jennings, 52, Northwest DC

Sport: Field hockey

Games: 1996, Atlanta

Post-Olympic life: Head coach of women’s field hockey at American University

“I got put into it completely at random. I went to Walter Johnson High School in Bethesda and had to take field hockey in PE class my freshman semester. The PE teacher talked to the head coach about me. The head coach saw me play and reached out to somebody in [a local amateur] league. Suddenly, this guy called me up. He wouldn’t let me get off the phone until I agreed to go to a training session. A week later, he picked me up, and the rest is history.

“[At the Olympics,] we came in 12th, the last place. It was devastating. You don’t have a lot of people to talk to about what that specific experience is like, and you kind of don’t want to relive it. So you just process it as best you can. I would say it definitely took at least a year, if not more, to recover from that.

“I retired after the 1999 Pan American Games. [But] I eventually got to go back to the Olympics as an assistant coach [in 2008 and 2016] and have a more positive experience. My life would have been completely different had I not ended up playing field hockey in a gym class: All my travels around the world. My partner for life—my girlfriend. My career. It’s hard to overstate how lucky I feel to have had this twist of fate.”

Cara Heads Slaughter, 43, Arlington

Sport: Weightlifting

Games: 2000, Sydney

Post-Olympic life: Weightlifting coach/gym owner; USA Weightlifting International Coach

“My high-school track-and-field coach wanted me to lift weights to be more powerful for shot put. Women’s weightlifting was not [yet] an Olympic sport. The first competition that I went to, my sister and I were the only two girls. We borrowed singlets from the boys’ wrestling team in order to compete.

“[In Sydney,] I made a young, dumb, costly mistake. You’re managing body weight to be as strong as you can be but also stay within the weight class. The rule back then was that if both athletes lift the same weight, the lighter person will break the tie. So because I had lost on body weight during a previous competition, I said to myself, ‘That will never be the case again.’ I manipulated my diet in such a way that it actually depleted me and unfortunately affected my performance. I placed seventh. It stung, but it informed how I coach today—how I try to help athletes prepare for great opportunities.

“I wanted to coach weightlifting professionally, but I didn’t pursue it initially because I didn’t see anyone that looked like me. There were no Black women in leadership in my sport—most of the coaches were white men. Probably around 2011 or 2012 is when I noticed that CrossFit was becoming popular. And one part of CrossFit is Olympic weightlifting. So suddenly there’s an audience.

“My personality is such that I don’t talk about the Olympics unless it’s related to my business or something like that. My husband was the one who actually felt like, ‘We need to put some of your memorabilia in a shadow box.’ They were just, like, in drawers and boxes.”

Scott Steele, 63, Severna Park

Sport: Windsurfing; silver medalist

Games: 1984, Los Angeles

Post-Olympic life: Coaching; sales manager at Ullman Sails Annapolis

“We raced seven different days. I wasn’t one of the larger and bigger competitors. So the wind I was looking for was a little bit lighter. The last race got very windy. The Dutch guy got away, so he’s off basically sailing around the course to win his gold medal. Obviously, my own country, I got more cheers than the guy who won the gold, so that was pretty cool.

“Right after the Olympics, one of the neat things that happened was that as medalists, we were able to do a tour around the country. The Southland Corporation—7-Eleven—put this all together and chartered some planes for all the Olympic medalists. We were given privileges that you would never have today. We were able to sit up in the cockpit with the pilot. In LA before we left, Ronald Reagan and Nancy—we all had pictures with them and also had a nice breakfast with them.

“I ended up continuing in the windsurfing industry all the way up until ’92, when I started having children. When my kids were growing up, the teachers heard I had an Olympic medal, and of course I got dragged into the classroom on career days. I always stayed within the sailing world. I do a lot of coaching, and I sell sails. I do have it on my business card that I’m an Olympic medalist. It helps a little bit with business.”

Andrew Valmon, 56, Rockville

Sport: Athletics (4×400-meter relay); two-time gold medalist

Games: 1988, Seoul; 1992, Barcelona

Post-Olympic life: Head track coach at the University of Maryland

“I picked up the sport pretty late. I was probably a sophomore in high school. But I had some success early. Seton Hall had a lot of 400-meter runners. I set the Big East record. After I graduated, I took a couple full-time jobs. One was with Eastman Kodak in marketing, and they were an Olympic sponsor, which allowed me to work full-time and also compete in the evening.

“My first Olympics, in Seoul, I don’t remember much. I was young, coming off of working full-time. I’m not so sure I had a full appreciation for making the team. Then in ’92, I did something that probably I wouldn’t advise people to do: I bought a plane ticket to Spain for my mom before the trials. That’s the mindset we had.

“You know, everything about those Games was different for me personally. I think back to new relationships, of having a full appreciation for a lot of sports that might have never been on my radar. But if you ask me what I remember most, it’s hard not to put the Dream Team [with Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson] first.”

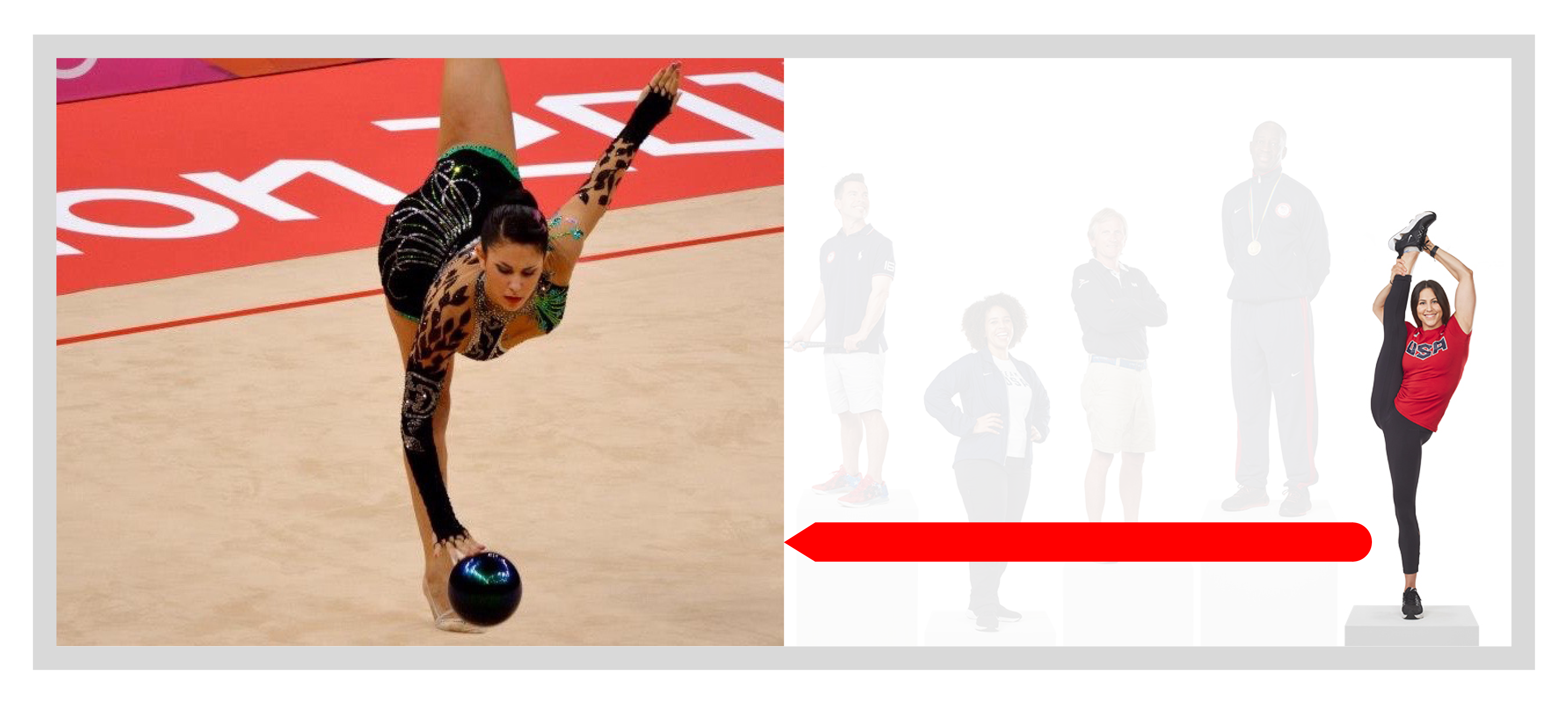

Julie Zetlin, 31, Bethesda

Sport: Rhythmic gymnastics

Games: 2012, London

Post-Olympic life: Head coach at Orangetheory in Tenleytown

“My mother was a Hungarian junior national champion; she found a club and wanted to see if I liked it. I ended up being obsessed, and it became an 18-year career. I was brought up in Bethesda, but we started a training program with Team Russia because in rhythmic gymnastics, Russia is the best. Our first camp, we went to their vacation training spot—Montenegro. I was turning 16. Their coach said she was going to make a selection with the girl she will help go to the Olympics. After the camp, she grabbed my arm and presented me to the US team and said, ‘This is your girl.’

“I went from being world finalist [in 2010] to [Olympic] qualifications while recovering from knee surgery, not knowing if I’d be able to compete. I ended up getting the wild card. [In London,] I learned I had a stress fracture in my foot. I couldn’t believe it. Another injury. After the first day, I was like, ‘I’m not going to get a medal.’ The second day, I was able to finish with happy tears.

“My [Orangetheory] clients assume that doing sprints or intervals is easier for me, but it’s not. Especially because I don’t have meniscus in my knees. I’m like, ‘I have to work just as hard as you to maintain my fitness levels and to get better.’ It’s a good way to connect with people.”

Credits: Photograph of Jennings courtesy of Team USA Field Hockey; Photograph of Slaughter by Alamy; Photograph of Valmon courtesy of U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee Archives; Other photographs courtesy of subjects.

This article appears in the August 2021 issue of Washingtonian.