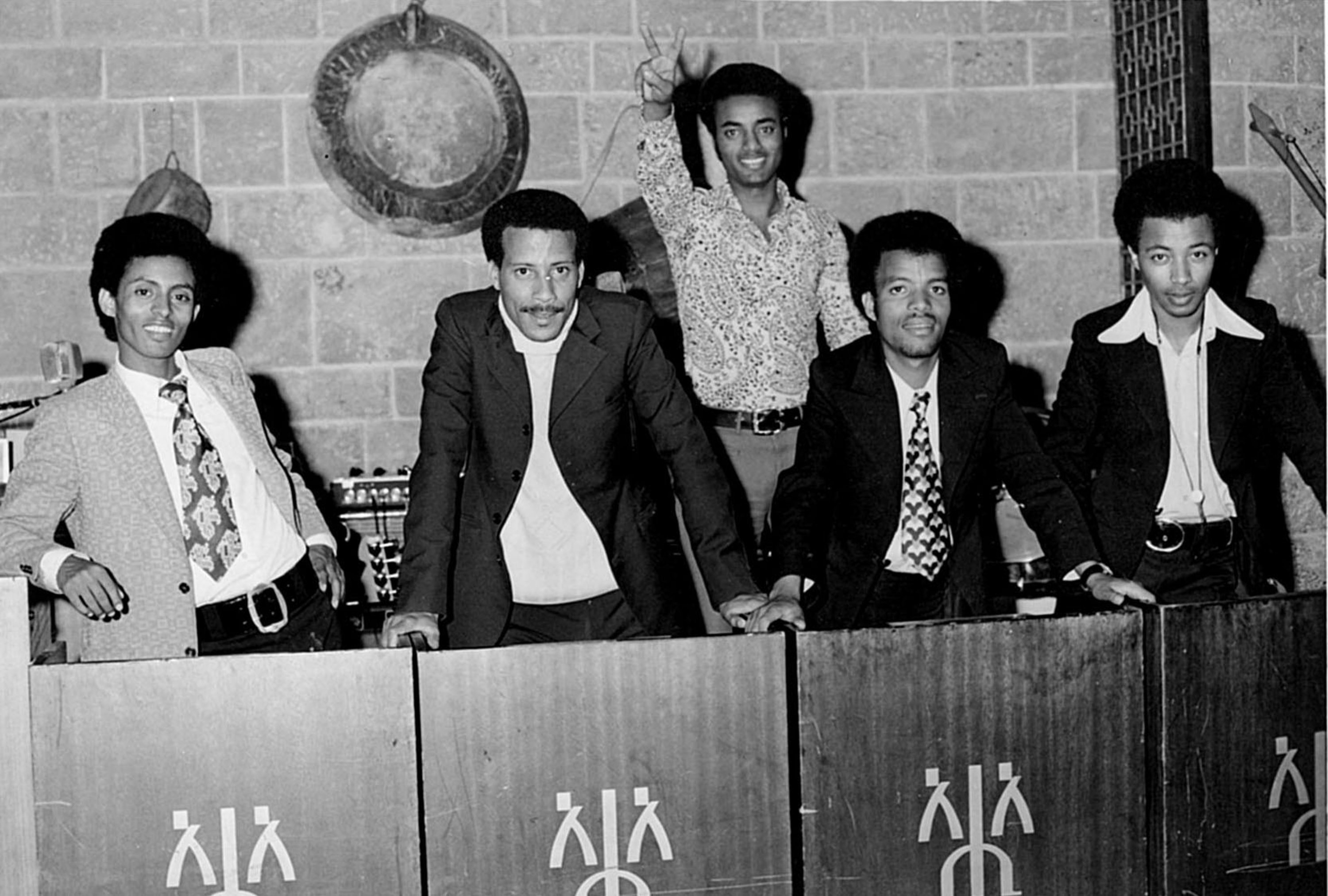

The Hilton Addis Ababa has long been a prime gathering spot for international notables and local sophisticates, and if you spent any time investigating its nightlife scene in the early ’70s, you might have run into diplomats and foreign dignitaries, movie stars and famous musicians. You would almost certainly have encountered Hailu Mergia. The organist and his group, Walias Band, were the Hilton’s house entertainers—one of the best gigs in town. During dinner, they ran through tinkly background tunes; later in the evening, when the scene heated up, funk and soul songs lit up the dance floor. It was a prestigious engagement for local musicians, and Walias Band was one of Addis’s top bands at a time when Ethiopia was—as much of the rest of the world would only later realize—producing some of the globe’s most exciting sounds.

Then, on September 12, 1974, Ethiopia’s emperor, Haile Selassie, was arrested at his palace and a Marxist-Leninist military junta, known as the Derg, seized control of the country. Selassie was put on house arrest, and he died, under unclear circumstances, in 1975. The Derg soon proved to be a brutally repressive regime, torturing and killing tens of thousands of people in the ensuing Red Terror campaign of 1977 and ’78. The horrors of that era also transformed Washington into a capital of the Ethiopian diaspora. Thousands of refugees turned up in the area, and eventually Mergia would move here as well.

As it happened, Selassie’s Jubilee Palace sat diagonally across from the Hilton. But even though some of these terrifying events were taking place just a short walk away, Mergia and his band were relatively insulated from what was happening, protected as they were by the prestigious hotel gig. “After the revolution, everything was not good,” he recalls. “A brutal government came in—the whole thing was changed after the Derg government. Sometimes you have people that were dead in the street. Even though we were okay by playing at the Hilton hotel, when you look at what was going on outside, we don’t like it. But we cannot do anything about it.”

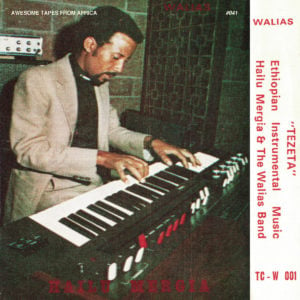

As the country was grappling with the aftermath of the revolution, Mergia and Walias Band quietly put out their first album in 1975. The recording bears no apparent sonic trace of those tumultuous times. Called Tezeta, it features nine wistful instrumentals that blend jazz, soul, and traditional Ethiopian music. The title tune is an Ethiopian standard—“to me, like a national anthem,” Mergia says. “The music is so beautiful. It’s a forever kind of melody.” Tezeta means “nostalgia,” and the music’s blend of joy and melancholy makes him think of old friends, lost family members, and his long-gone life in Ethiopia.

When it first came out, the self-released Tezeta was sold only on cassette. The music is both transporting and timeless, an essential document of an important period and place in music history. Even after Mergia moved away from Ethiopia a few years later, almost nobody outside of the country ever heard it.

Until now, that is: Due to a highly improbable set of circumstances, the album has finally been reissued, joining a handful of other rediscovered classics that bear Mergia’s name.

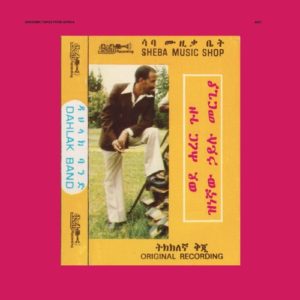

In the years after Tezeta came out, Mergia continued to perform in Addis Ababa, recording more albums with Walias Band and backing prominent local vocalists. Then one day in the late ’70s, he was contacted by Amha Eshete, a key music producer and label owner who had moved to DC. Eshete wanted to bring some musicians to the US for a tour. Would Mergia’s band be interested? (Eshete, who operated the Ibex club on Georgia Avenue, died in April.) It took a couple of years to make the tour happen, but in 1981 Mergia and his bandmates finally arrived.

It turned out to be much more than a chance to see America—it was an opportunity to escape the situation in Ethiopia. Mergia and three of his bandmates decided to remain in Washington. He has lived in the area ever since.

At first, Mergia struggled to adjust to his new life. Sweating it out in the American club scene was tough compared with his high-end Hilton existence in Addis Ababa, and making it as a working musician in DC proved to be a difficult path. “The hardest part was the loneliness,” Mergia says. “That was the loneliest time I remember in my life. It was a little bit confusing for me. I was asking myself why I stayed here.”

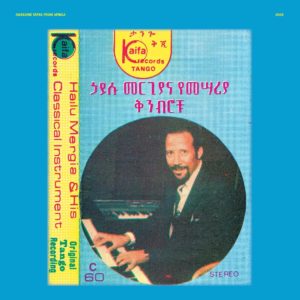

But eventually Mergia settled into his new city. He started taking music classes at Howard University, and in 1985 he used a small studio to record a solo album—a collection of spaced-out accordion and synth improvisations that was released back in Ethiopia and attracted significant attention there. In the US, however, its existence went entirely unnoticed.

Mergia’s interest in the music business eventually faded, and in the ’90s he started driving a Washington Flyer taxi, ferrying passengers who only occasionally recognized his famous-in-Ethiopia name. He kept a keyboard in the trunk so he could practice on his breaks. But Mergia thought his performing days were basically over.

Mergia’s comeback began, unlikely as it may sound, when a guy named Brian Shimkovitz was on vacation in Ethiopia in early 2013. Shimkovitz, a former music publicist with a degree in ethnomusicology, runs a website and record label called Awesome Tapes From Africa, and during his trip he would stop by music stores and ask if they had any old cassettes in the back, hoping to find fodder for his site. One day in Bahir Dar, after a fruitless search, he was on his way to the hotel when he noticed a little electronics store. Shimkovitz went in and asked his question, and the clerk pulled out a stash of outdated albums. “I remember briefly seeing this blue tape, and he played it for a second,” Shimkovitz says. “I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m definitely buying that.’ ”

When Shimkovitz returned to Germany, where he lives, he put the album on. “It was getting to be after midnight, and I listened to it twice all the way through,” he says. “It was just so good. Every single song was so compelling.” The name on the tape was Hailu Mergia. Shimkovitz was familiar with Walias Band, but while he had heard of Mergia, he didn’t know much about him. A quick Google search brought up a website with contact info. “I was like, ‘That’s a DC cell number!’ ” Shimkovitz says. “I just called him up.”

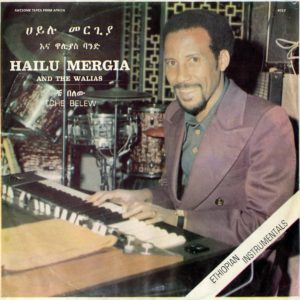

The tape turned out to be the album Mergia had recorded in 1985. Awesome Tapes From Africa reissued it later in 2013, under the title Hailu Mergia & His Classical Instrument. There was something intoxicating about the unique sounds he had captured in that small studio, and the attention and accolades that ensued changed Mergia’s life. “Since that time,” he says, “I am back into the music business.” Mergia returned to the stage, playing gigs around the US and abroad. Further reissues followed, and in 2018 he released his first album of new music in decades, Lala Belu. Yet despite all of Mergia’s success, that initial album, Tezeta, remained forgotten.

In the end, Tezeta’s path to rediscovery was just as twisty as that of Hailu Mergia & His Classical Instrument. In 2012, several months before the trip to Ethiopia that led him to Mergia, Shimkovitz had received a package in the mail from a man in Holland who’d lived Africa in the 1970s and owned a bunch of tapes that he thought might be of interest. One of them was an old dubbed cassette that had “Ethiopie – 1976” written on it in pen. Shimkovitz liked the music but had no idea what it was, so he stashed it away in a box.

Years later, it occurred to Shimkovitz that Mergia might be able to identify the intriguing tunes on that cassette. “He was like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s one of my tapes,’ ” Shimkovitz says. “ ‘That’s me.’ The second he said that, I was like, ‘Oh, duh, of course it’s Hailu.’”

Tezeta is transporting and timeless, an essential document. Almost nobody outside of Ethiopia ever heard it.

When the pandemic hit last year, Mergia was forced to cancel a European tour and didn’t have much to do. Shimkovitz thought back to that early recording, which was by that point so obscure, it wasn’t even listed on the websites that international Ethiopian-music fans use to track recordings. If they were to reissue it, Tezeta would “add a lot of detail to the overall picture of that musical period that so many people around the world are obsessed with,” Shimkovitz says he told Mergia. “It was kind of a no-brainer because it’s such an important part of the story.”

If you ask Mergia about his life in Ethiopia around the time of Tezeta, he doesn’t sound all that eager to talk about it, keeping his answers politely vague. In general, he seems to communicate best with his keyboard. “He is a gentle, soft-spoken, unpretentious individual who has seen a hell of a lot of stuff in his life and knows a lot about human character,” says Shimkovitz. “But he sits and he watches and he observes. He just really wants to play music. Like, when you go and see him at a random city in Poland, he is letting you have it—every single night, trying to do something different and really challenging himself.”

That’s been harder to do during the pandemic, but Mergia is used to performing just for himself, practicing alone as he did in those years before his comeback. Today, Mergia lives in a house in Fort Washington with his wife and stepson. He retired from the taxi business a few years ago, so he spent the shutdown months at home, with plenty of time just to sit and play.

In April 2020, Mergia released another album of new recordings, called Yene Mircha. He says he’d like to make more such records, although he doesn’t know what form they might take. Shimkovitz hopes to put out more of Mergia’s old music as well. That cassette from the Dutch guy’s collection also contained five even older tracks that aren’t included on the Tezeta reissue—songs that could come out in some form down the road.

For Mergia, all of this interest in his musical past is gratifying. But while most people are just now discovering the Tezeta, the music has been there with Mergia all along, keeping him company as his life in Ethiopia—those long nights at the Hilton, the heady music scene of ’70s Addis Ababa—has ever steadily receded. “When I listen now, I have so many things I’m thinking about,” Mergia says. “Before Brian Shimkovitz released it, I used to listen to this music once in a while at night. I love it. [But] sometimes I don’t like to listen to Tezeta because it takes me way down. What happened to my friends and everybody?” Still, Mergia is excited that people can finally hear this vital early work. “Tezeta,” he says, “has a lot of memories.”

This article appears in the August 2021 issue of Washingtonian.