Hayden Wetzel is a retired federal worker with a passion for local history and a habit of walking around his Brookland neighborhood in search of interesting old stuff. One of his favorite finds is a pair of vintage Quonset huts that he spotted years ago on a site near the Metro tracks. “They’re just neat,” says Wetzel, who volunteers with the DC Preservation League and has worked as a tour guide. “They seem to be unique in Washington. They’re part of the semi-industrial history of the city.”

Not long ago, Wetzel learned that these cool old structures are due to be torn down. A shiny new housing complex is in the works, with plans that include three buildings, 723 apartments, and—alas—no prefabricated temporary edifices from the 1940s. “So I decided, well, that’s the end of the Quonset huts,” Wetzel recalls. “Unless maybe something can be done?”

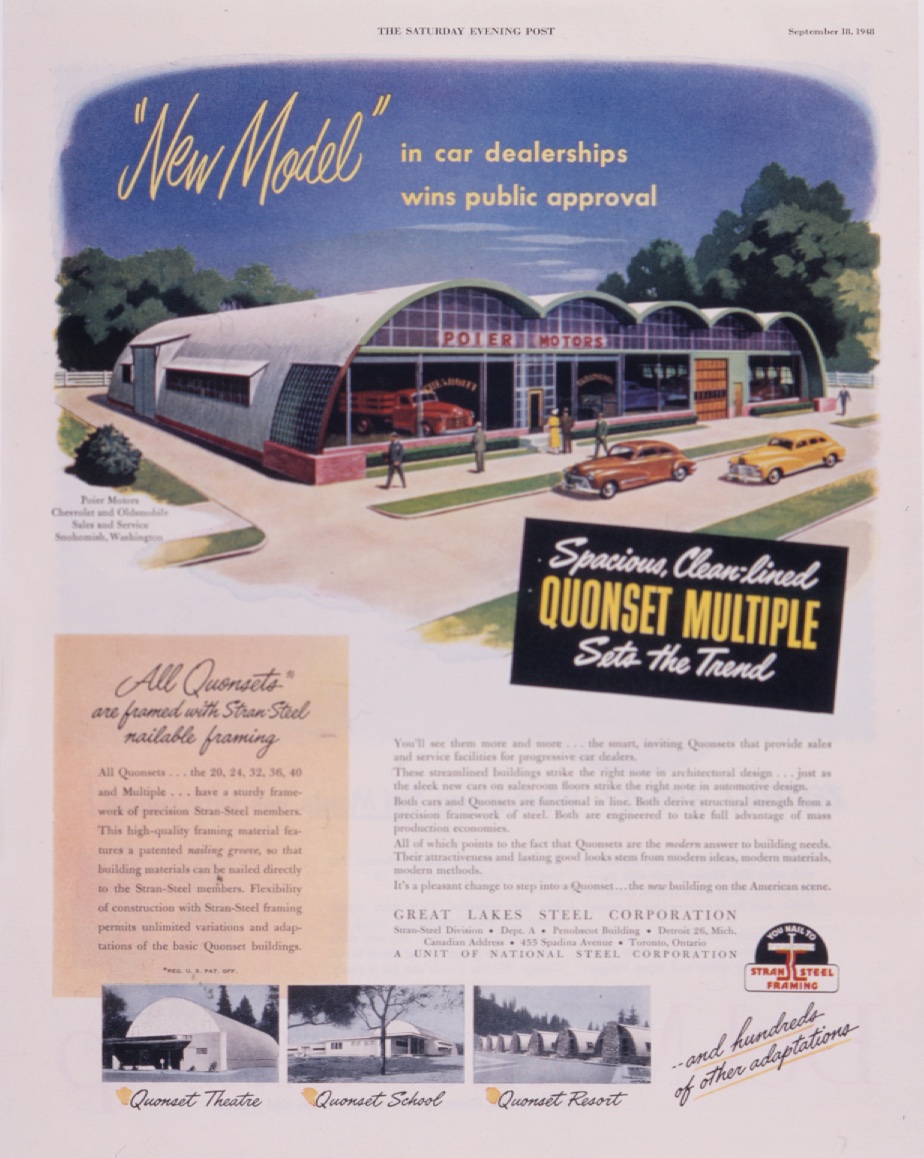

Quonset huts were developed during WWII for the US Navy, which needed quick-assembly utility structures; after the war, various companies sold them for civilian use. “It was space that could be easily acquired at a low cost,” says Chris Chiei, an architect who coedited the book Quonset Hut: Metal Living for a Modern Age. “We’re not talking about something that was intended to be passed down through time.”

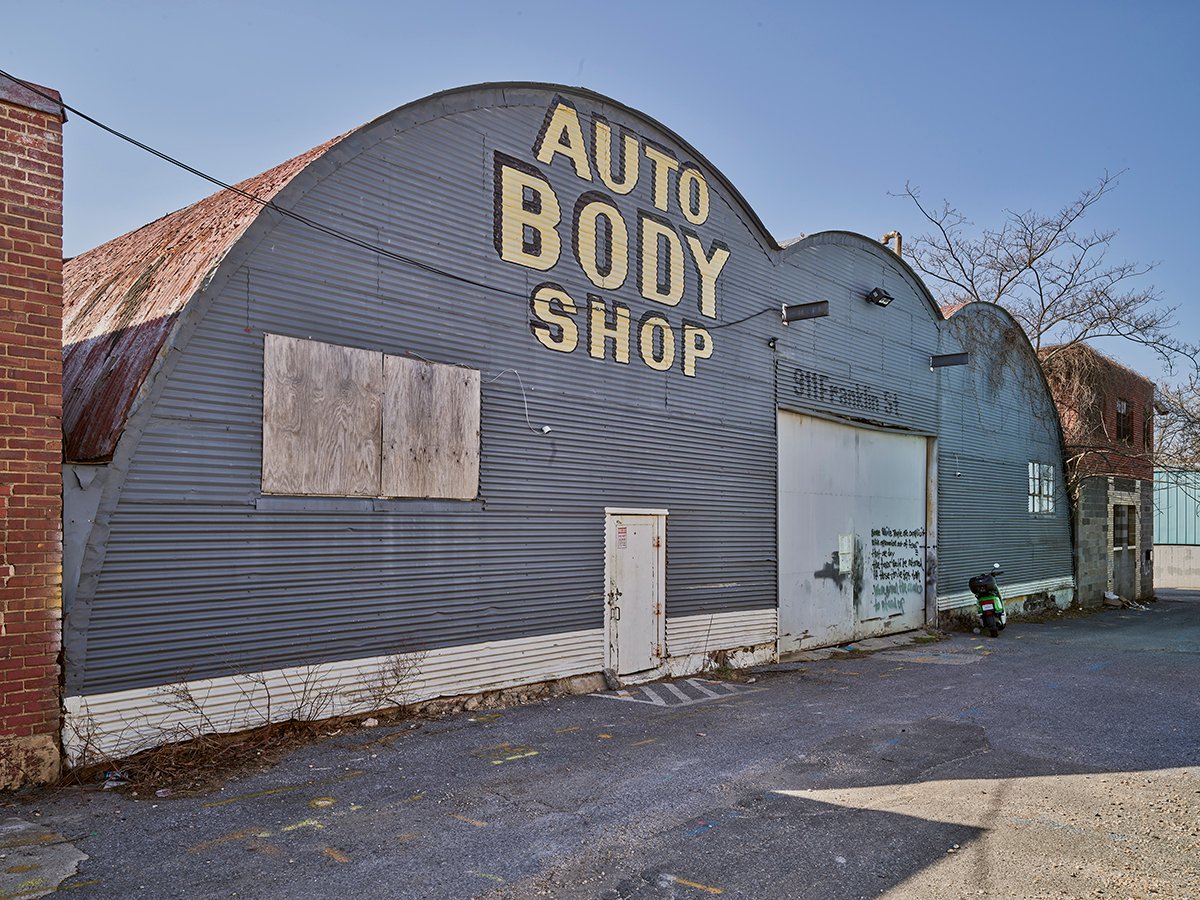

Located near Franklin and Tenth streets, Northeast, the Brookland huts have outlasted any reasonable expectations for the lifespan of a Quonset, with one still in use as a car-repair business and the other—a rare three-arch version—currently empty. Made of corrugated steel and in somewhat gritty condition after years of hard use, the structures are easy to miss if you just happen to be passing by. But for anyone with a fascination for the past and an eye for urban character, the things have an undeniable rough charm.

They were built by Detroit’s Great Lakes Steel Corporation and installed in the 1940s, according to the original building permit. The lot was then owned by members of the Gichner family—a name longtime Washingtonians might associate with the Fred S. Gichner Iron Works, which did ornamental metalwork for many prominent buildings around town, including the White House and National Cathedral. (That business was located elsewhere.)

Intrigued by the huts’ history, Wetzel and a few other like-minded Washingtonians are now trying to save them. That would mean trucking them to a new location, because the prefab structures aren’t the kind of things that would qualify for onsite historic preservation. Quonsets were designed to be movable, so in theory, they could be relocated. Maybe they could be used in some light-industrial capacity, Wetzel says, as they have been for the past 75 or so years. Or perhaps a museum would want them (he’s reaching out to places like the College Park Aviation Museum and the National Museum of the US Navy). They might even work as a funky covering for a beer garden or outdoor restaurant.

It’s a long shot, though. So far, nobody has expressed much excitement about the idea of taking the huts. The most likely scenario is that this pair of intriguing relics will—like so many of their ilk around the country and the world—just get leveled. Which means that anyone with a penchant for local curiosities should check them out now, before the bulldozers show up. “If you live in DC and—as some of us do—cut notches on your walking stick as to how many places you visit that the average person doesn’t know about, these Quonset huts are one of them,” says Wetzel. “There are lots of interesting, unknown places in DC to visit. They’re not grand, but that’s the fun of visiting them.”

Recently, one visitor to the Brookland Quonsets was Carolyn Gichner, whose parents, Lawrence and Gertrude Gichner, owned the property for much of the huts’ early life, renting them out for extra income. Carolyn hadn’t seen the huts since the 1950s, when she was about ten. But as soon as she pulled up in front, she recognized them, recalling times when she’d come down with her father to pick up rent checks. “I feel nostalgic,” she said, gazing at the metal semicircles that made enough of an impression to stick in her mind for the last 65 years. “I do remember. Isn’t that the strangest thing? It’s there.”

Eventually, the Gichners sold the triple-arch Quonset to Richard Ross and Philip Savopoulos, who ran an ironworks out of the space. Savopoulos had a son named Savvas, who—much like Carolyn did when she was young—sometimes came by the Quonsets. Ross and Savopoulos ended up being business partners for many years, running a major company called American Iron Works. Savvas eventually took over the business. Perhaps his name sounds familiar: In 2015, he—along with his wife and son and their housekeeper—was killed in what’s come to be known as the “mansion murders.”

Ross is now retired and lives in Delaware, but he’s never forgotten the Quonsets. Decades after he sold the property, he still likes to drive by, just to reminisce. “It’s really part of my soul,” he says. “It would be great if it could be moved. If it’s not there, it’ll be like part of my life got erased.”

Carolyn Gichner would also be sorry to see the huts go. After her recent visit, she headed back to her house in Cleveland Park, knowing she might never see them again. “To me, it’s sad,” she said in the car. “No matter how decayed, they’re part of history.”

This story appears in the April issue of Washingtonian.