Chef Kwame Onwuachi wears a lot of hats these days—more than your average celebrity toque. The 32 year-old, who started his DC restaurant career with the short-lived Shaw Bijou and Wharf hit Kith and Kin, now lives in Los Angeles. His lauded 2019 memoir, Notes From a Young Black Chef, is being turned into a feature film starring LaKeith Stanfield. And Onwuachi’s getting into acting, too; his first movie, Sugar, comes out on Amazon Prime later this year. He’s an executive producer for Food & Wine. He even has his own line of nail polish (yes, really).

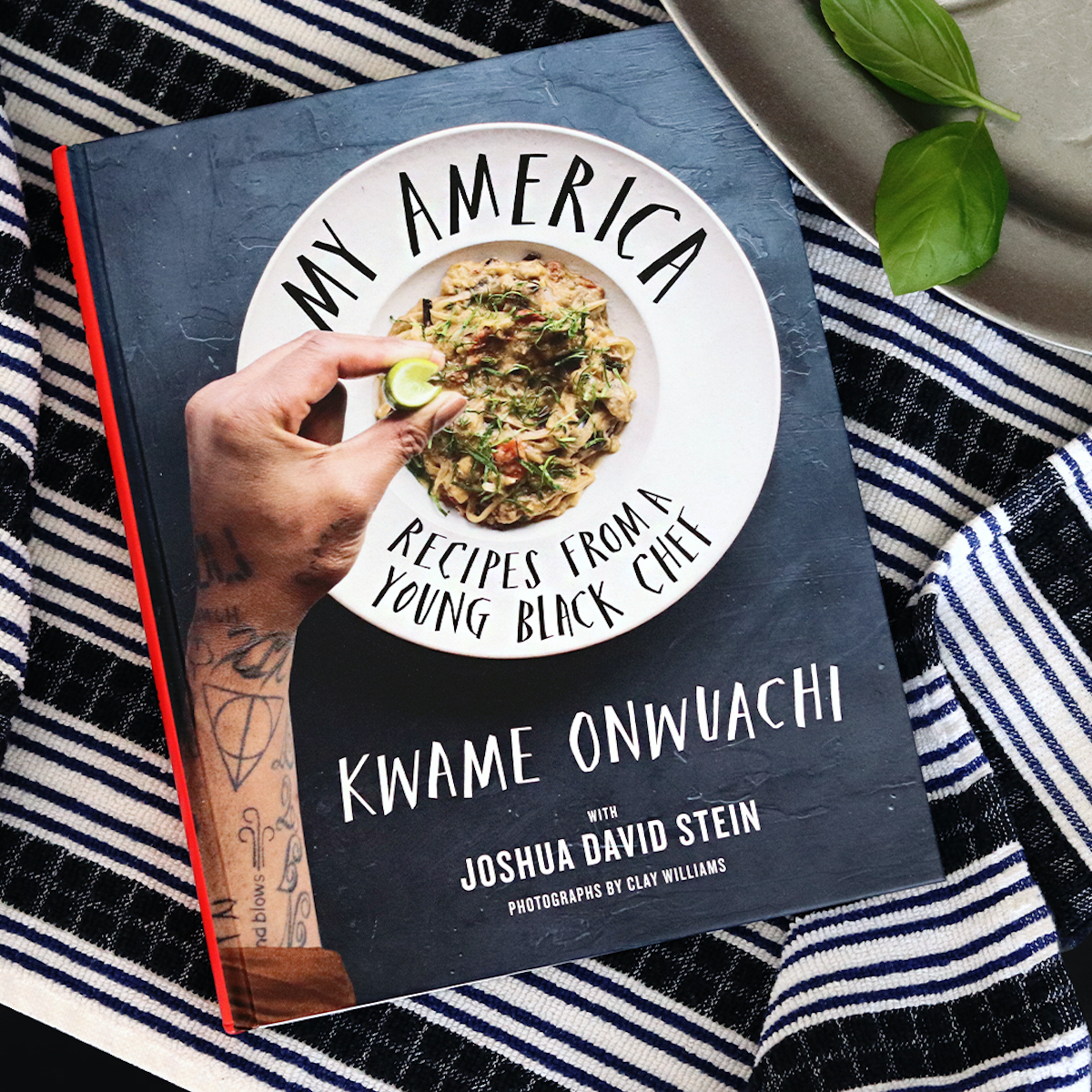

Now Onwuachi can add cookbook author to the list. His first recipe collection, My America: Recipes from a Young Black Chef, is out Tuesday, May 17. Through its 125 recipes, the cookbook/memoir/historical exploration intertwines Black culinary traditions with Onwuachi’s own roots in the Bronx, Nigeria, Louisiana, and beyond.

Onwuachi will celebrate the book’s launch in DC this week with a series of events, starting with a discussion with Nina Oduro of Dine Diaspora at Sixth & I on Tuesday, May 17 (tickets start at $18). Then on Wednesday, tickets ($90 per person) to a launch party at Maketto include bites inspired by the book, drinks, and a signed copy.

We caught up with Onwuachi to talk about opening and closing his DC restaurants, how he got into the nail polish game, his Harry Potter obsession, and what fame does (and doesn’t) do for him.

Your tattoos feature prominently on the cover of the book, as well as inside—and tattoos always tell a story. Tell me about yours.

“I have a timestamp on my hand that says “now.” Now is the time to do whatever you want. I have a little reminder to myself that says ‘dream’ in my own handwriting. I have the Roman numeral 19 because 2019 was the year my life really changed. Me and [Georgia pit master] Bryan Furman have matching tattoos. And I have a Deathly Hallows tattoo because I’m Harry Potter. Go Gryffindor!”

I love the opening lines of My America: “Show me an America made of apple pie and hot dogs, baseball and Chevrolet and I won’t recognize it. That’s a foreign land to me. Maybe that’s someone’s America but it isn’t mine.” What about your America did you want to show the reader?

“When you think about eating as a child, you’re not like ‘what nationality is this?’ You’re just eating food, thinking that’s how everyone eats—until you get out of the house and realize everyone has their own personal journey with food. This book encapsulates everything I grew up eating.

In your introduction, you write about your first-ever restaurant, the Shaw Bijou, and say: “I went to great lengths to tell my own story, the story of my childhood and my travels, expressed in true decadence. The halal chicken and rice I ate growing up became a rice chip with lamb sweetbread glazed in chicken jus…But it was an autobiography—of one man, me—and looking back on it in hindsight, it was an autobiography written in a borrowed tongue.” Why do you think it was hard to convey your true voice there?

“I think people had their minds made up before the restaurant even opened. Articles were written about the restaurant talking about the price before people even dined there. I think maybe people weren’t ready for that experience. I look back at that a lot—I know I put out some amazing food, and gave some of the best service, and had an amazing environment. If anyone else opened that restaurant now it would critically acclaimed—the different rooms, dining as theater, telling a personal story. [One critic] said it was like a ‘cult,’ Kwame telling his story. But every chef tells a story.”

You write about Kith and Kin [at the Wharf] as a period of exploration and growth, and how opening a fine dining Afro-Caribbean restaurant connected you to your family and their recipes. What did the restaurant mean to you?

“It meant so much for me to put my culture on a plate in a setting such as that. Afro-Caribbean, and most cultures that are not European, their food is banished to these mom and pop shops—which are great, I eat there three to four times a week. But being able to celebrate a special experience while also celebrating your culture, that’s something I hadn’t seen. I thought it was the most diverse fine dining room in DC and arguably the country at the time. You saw all walks of life—there were people who were able to celebrate while eating oxtails, and there were people who’ve never heard of oxtails, sitting side by side in true community. I remember when I first saw fufu leaving the pass, I cried, because I’d never seen our food like that.”

Do you have a favorite memory during Kith and Kin’s four year run?

“A young Ethiopian cook came to the restaurant in between service. He was like ‘I’m not looking for a job. I just want to talk to you. I’ve never had someone to look toward as a beacon of light in this industry, who’s so unapologetically themselves. Thank you for writing your book, because I’ve dealt with racism in Michelin-starred kitchens in DC, and you spoke out about how that’s not right. All I want to say is thank you.’ And we sat there and cried together. I was like, ‘I don’t know how to help you, but continue to stand in what you believe in and you’ll be alright in any industry you choose.’ But he left the culinary industry, and I didn’t blame him.

In My America, in your vegetable chapter, you write: “Long before kale became a bourgeois obsession, it counted among the brassicas that sustained generations of Black Americans.” Do you see this book as reclaiming, or refocusing, the stories around certain ingredients and recipes?

“Definitely. I don’t think you can talk about American cuisine without speaking about West African cuisine. So many people were brought over here and stolen, and with them came their pain, their culture, their practices, and their food ways. We were the ones that helmed the kitchens. So yes, I would say it’s reclaiming, and also reeducating—it’s always been ours.”

If you had to pick a recipe for a home cook to really get the flavor of your book, which one would you recommend?

“I’d say the jerk chicken. It’s similar to the recipe I served at Kith and Kin. We start by brining the chicken, we make the jerk paste from scratch. When you take the first bite it’s like people’s first time actually tasting jerk chicken, not some jarred sauce or something thrown in the grill. There are so many nuances to it, and it’s beautiful.”

Your final chapter of the book details your departure from New York, and the tone is bittersweet. What would this current, unwritten Los Angeles chapter sound like?

“It’s about getting back to what makes me happy. That’s the LA chapter if I had to write: doing things that make me happy, and walking into my purpose. I started acting, creating different brands, giving creative direction for different corporations, and really flexing my creative muscle.”

How do all these different pursuits impact you as a chef, and has the fame changed you at all?

“No, I think that’s what life is about. Just trying things. Tomorrow is not promised today. So it’s always best to just do what you want to do. The time to do anything is now. And I don’t think fame dictates anything that I do. I don’t look at myself as famous or anything. I’m the same kid who would go up in the playground and ask someone if they wanted to play. And I’m never going to change.”

Tell me about your nail polish line, and how it came about.

“It was four or five years ago in DC, actually. My nieces came to visit me and they asked me if I would go with them to get their nails done. I got all black and I was like ‘oh, this shit fly.’ I’ve been wearing [nail polish] since, and then Orly reached out to collab and we worked on it for the greater part of a year. I wanted to align myself with things that I actually like, things that I actually wear, things that really represent who I am. So it’s just another form of self expression. I think more men should get into it. It’s breathable, so it’s good for the kitchen.”

Do you see yourself returning to restaurant kitchens eventually?

“Eventually, for sure. When the time is right.”

If you could open your dream restaurant, where and what would it be?

“It would be back in DC. I’d be serving food from my childhood, in whatever capacity. So that means a bunch of different cultures.”

What’s coming up next?

“The main thing that’s coming up is The Family Reunion [a four day food festival at the Salamander Resort in Middleburg, Virginia]. When I came on board with Food & Wine, I really wanted to do something different that hasn’t been done before, in true Kwame fashion. And I wanted to do an event that celebrated Black and Brown contributions to the food industry. I’ve been to so many food events, and there’s usually only one of us there. We have over 45 chefs and writers and entertainers, and we have panel discussions, breakout sessions, performances by musical guests, comedians. We start with the cookout. I don’t think you can have a Black event without a cookout, but instead of your uncle behind the grill, it’s Rodney Scott, Bryan Furman, and Virginia Ali slinging half-smokes. We’re doing a Jamaican dance hall night with a lineup of super Caribbean chefs. I think people, for the first time, leave a food event with their hearts and minds full, not just their bellies and livers.”

My America has already garnered a lot of praise. What is your hope for the book and its impact on home cooks and the dining world in general?

I think this book should be in every home cook or chef or culinary student’s or library. Just like everyone has The French Laundry Cookbook, The Food Lab, or The Flavor Bible. I think this is up there because it tells a story of people that are in America that have made it their home. It’s also people that help build America, so I think their stories need to be told.”