When you pass through the iron gates of Georgetown University—into a lush quad of Gothic spires and tolling bells—you enter a spawning ground for elite politicos, one of the most fertile in the world. Year after year, a ridiculous number of Georgetown students believe they’re destined for power. More than a few end up right. Upon this lawn have strolled scores of future senators and Congress members, ambassadors and cabinet secretaries, operatives and lobbyists, plus a President, a Supreme Court justice, and a smattering of leaders abroad.

But if the political future of our nation resides at Georgetown, then something alarming is afoot. These days, the campus loathes student government. And when voters hate their government, odd things can happen at the polls. Take the school’s most recent election—and stop me if this sounds familiar. A flawed establishment candidate becomes a magnet for voters’ ire. A charismatic outsider draws disaffected voters to their cause. One side fails to consolidate, assuming their opponent is a farce. Scandals abound. Voters grow nihilistic. The candidate with the most votes doesn’t win.

It’s a spooky thing to contemplate, that a crew of baby politicos accidentally reran 2016—the election that quasi-broke America and never seems to end. Concerned, I spent my summer drenched in Georgetown politics, catching the vibes of tomorrow’s overlords, all to answer a fearsome question: What if the worst is yet to come?

The first thing to know about Georgetown’s student government is that last November, when it tried to abolish itself, it failed.

The first thing to know about Georgetown’s student government is that last November, when it tried to abolish itself, it failed.

The plan, I guess, was to scrap the Georgetown University Student Association and create a more functional government—a crackerjack proposition among the student body, who voted for “Abolish GUSA” three to one. But in a blow to GUSA’s already dismal reputation, the referendum didn’t draw sufficient turnout to pass. Student government was apparently so ineffective, so disconnected from campus life, that it couldn’t even whip the votes to self-destruct. The stench still lingered in January when the election for GUSA’s next president and vice president began.

At first, only one ticket was running: a pair of insiders, Thomas Leonard and Nirvana Khan. They were earnest and qualified, with multiple years in student government—which struck voters as an unscrubbable establishment taint. Their campaign branding was vaguely corporate, and attempts to humanize themselves fell flat: Thomas, a junior from suburban New York, was once cast as an Oompa Loompa! He and Nirvana, a Texan who loves chicken jalfrezi, were both born under Scorpio moons!

View this post on Instagram

Worse, other insiders didn’t like them—at least not the ones talking extremely specific shit online. Was Thomas ableist for asking a student leader to attend meetings during a mental-health crisis? Did Nirvana once “co-opt the identity” of another senator by accidentally sending an email from her account? To the average student, the details were a wash, but the squabbling formed a ruinous gestalt: This campaign was a circular firing squad, typical GUSA, exactly the dysfunction everyone loathes.

Conditions were ideal for a bombastic alternative. Sophomores Kole Wolfe and Zeke Ume-Ukeje bounded into the race as champions of the frat constituency, so foreign to GUSA that they repeatedly mispronounced its name: “goose-uh” instead of “guss-uh.” And in their bid to helm “goose-uh,” they made tantalizing promises to the nightlife crowd, such as defunding the university’s noise-complaint cops. “Their campaign was run as, like, the partying campaign,” says Darren Jian, a student reporter. “Basically, making Georgetown a fun experience was the core message.”

I know, it’s a cliché—the American electorate routinely pulls the lever for the more amicable quaffer of beer. But Georgetown students? They’re political sophisticates. These clowns didn’t have a prayer.

A stereotypical GUSA kid is mad with pseudo-power. She’s already hatching her 2048 presidential run; he’s too consumed with speechifying to bother addressing campus needs. Students see GUSA as a hive of Tracy Flicks, pompous adolescents ablaze in meaningless drama, cosplaying their grandiose political ambitions on an insignificant stage. “A joke” is how one student describes his government. “You don’t really see them doing a lot, except causing scandals, resigning, and being replaced.”

Structurally, GUSA resembles the federal government—but it functions more like the UN. The GUSA Senate is a prolific passer of nonbinding resolutions—ones demanding housing and dining refunds or supporting DC’s attempts to decriminalize sex work—but these cris de coeur seldom rouse the university administrators who actually call the shots.

And if an institution isn’t powerful, who cares who runs it? One student, we’ll call him Josh, once thought that way—until he became the leader of a student group and learned to bend a knee. In that role, he says, “I figured out what GUSA was useful for, which in my opinion is one thing: They control the allocation of the million-dollar student-activities fund.”

At Georgetown, GUSA is a kingmaker of extracurricular life. Student groups—the outdoors club, the a cappella kids—submit their budgets, and (in a bewildering system that Josh says resembles the US military appropriations process) GUSA allocates the cash. In addition, GUSA has its own budget—in the range of $15,000 per year—which has lately gone to ambitious use. The administration of Nile Blass, the outgoing GUSA president, bought laptops and accessibility equipment for low-income students and negotiated summer housing for those without somewhere to go.

Blass left office enormously popular among the sliver of students who follow GUSA, but she barely moved the needle on overall student disdain. Josh, who already talks like a CNN analyst, deems this a “massive communication failure”: “GUSA did a great job, but then you have to make sure people know you did a great job, and I don’t know if that happened.”

The message certainly didn’t reach Kole and Zeke. Here’s the hook from their launch video: “During your years at Georgetown, how familiar have you been with GUSA or its policies?” Kole asks. A beat of silence. “Exactly,” Zeke replies. Their promise, essentially, was to engage the entire campus with student government—not simply the insular friend group who’d been involved with GUSA before.

View this post on Instagram

Maybe this message sounds inclusive—or at least like a milquetoast platitude—but in GUSA circles, it was a dog whistle. At an abundantly white and wealthy school, GUSA had lately become browner, lower-income, and less male. Perhaps more privileged students hadn’t felt the effects of its recent initiatives—the laptops, the wheelchairs—and now, believing that the body wasn’t effective, they wanted to take it back.

Turning this rift into a chasm was the issue of Georgetown’s mask mandate, which Kole and Zeke sought to overturn. This was an utterly empty promise—GUSA doesn’t dictate mask policy, a technicality of which the candidates seemed unaware. Still, the pro-mask backlash was ferocious: Did Kole and Zeke wish to see the immunocompromised die? This caught the pair off-guard. “We didn’t see masks as a polarizing issue,” Kole says. “In this specific situation—in a place where 99 percent of people are vaccinated and we’re all college-age people—we just thought the mandate was not really practical.”

Kole Wolfe and Zeke Ume-Ukeje bounded into the race as champions of the frat constituency. “Their campaign was the partying campaign. Basically, making Georgetown a fun experience was the core message.”

While lots of students agreed that the mandate was overzealous, Kole and Zeke were cast as the outsiders, the frat bros trying to put progressives in their place. Now they were anti-mask, too. It didn’t help that they had few qualifications for office, or that they’d given a couple of disastrous interviews to campus papers that left the impression, in the words of the Georgetown Voice, that “the pair was jaw-droppingly unaware” of the work of student government. That same editorial labeled Kole and Zeke “the worst GUSA campaign in recent history” and suggested that their lack of knowledge might be “dangerous.”

The narrative became, in Kole’s words, “that we are the Trumpian frat boys that have no idea what’s going on and are evil and want to disenfranchise people.”

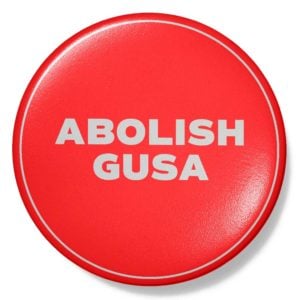

For years, disgruntled voters have punished GUSA at the polls. Back in 2016, two sandwiches from the campus deli—the “Hot Chick” and the “Chicken Madness”—finished second in the GUSA executive election. Later that year, the Chicken Madness won a Senate seat. So there was precedent when the spoof campaign of a Star Wars villain caught fire.

“Most members of GUSA lie about their intentions in order to gain power. On February 10, vote for a candidate who is honest about his desire for complete and utter control.” This was the first missive from @palpatine4gusa, the Instagram of the Emperor Sheev Palpatine. His “campaign manager,” freshman Matt Shinnick, got the idea from a joke he’d been making: that “even a genocidal Sith Lord would be better than these options.”

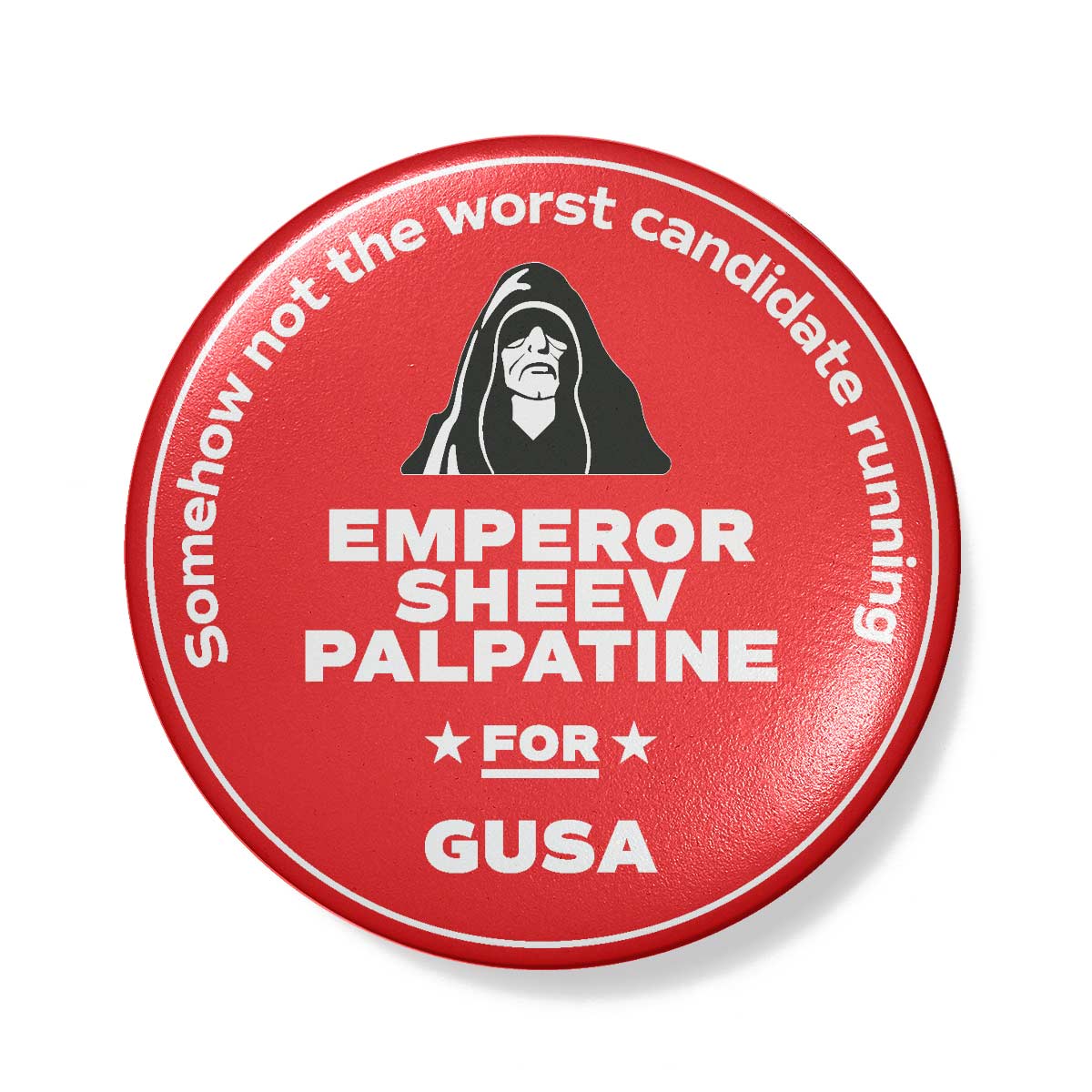

Palpatine basked in the other candidates’ foibles. The establishment campaign caught flak for its slogan: “Girlboss GUSA, Gaslight Admin, Gatekeep Student Rights.” The tone was cringe, like politicians trying to sound relatable—Hillary telling the youths to “Pokémon Go to the polls.” And the phrasing was also confusing. Did the candidates plan to keep students from their rights? To mistreat Georgetown administrators? “We do not literally intend to psychologically manipulate or abuse anyone while in office,” they clarified. “Manipulate the Jedi, Mansplain the Force, Malewife the Mandalorian,” Palpatine gleefully ’Grammed.

Kole and Zeke would not be outdone. The night they announced their campaign, student revelers descended on Abigail, a nightclub in Dupont Circle. They danced beneath an illuminated “Wolfe Ume 2022” sign while enjoying Grey Goose bottle service, which caught the probing eye of the GUSA Election Commission. Per Georgetown’s strict election rules, alcohol can’t be mixed with campaigning, and candidates are limited to $300 in spending. In a formal complaint, Thomas and Nirvana noted that bottle service at Abigail costs $375.

When the commission investigated, Kole and Zeke claimed this was not a ritzy campaign launch—their friend was simply out clubbing, and, being underage, they weren’t even there. They forked over bank statements and receipts but then stopped cooperating with the inquiry. Where they learned this strategy is anyone’s guess.

Some students lobbied to eject Kole and Zeke from the race, but the Election Commission simply cut their speaking time at the upcoming Zoom debates—a punishment with little practical effect. “Kole and Zeke didn’t offer constructive comments in the debates,” says Alexandra Bowman, who satirized the GUSA race in a campus publication. “They would say, like, ‘I don’t know anything about that issue.’ And they wouldn’t even try to pivot—they would just stop talking.” Less speaking time meant less opportunity for gaffes.

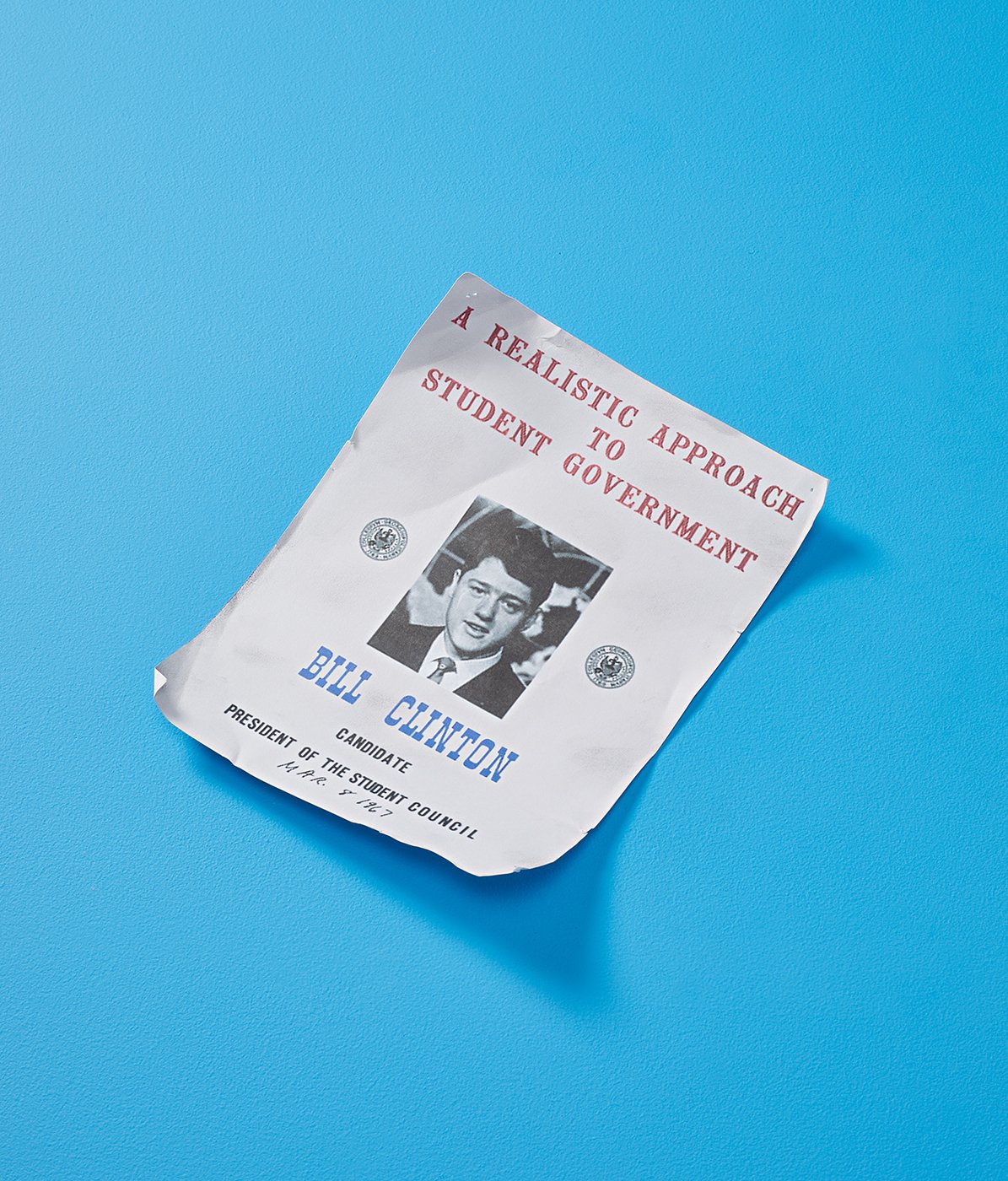

Another scandal-plagued candidate for Georgetown student government was William Jefferson Clinton, an ambitious sweet-talker from Arkansas who graduated in 1968. “A lot of people felt he was running for student-body president the day he stepped on campus,” says Terry Modglin, who beat Bill Clinton for the job in 1967.

Clinton’s version of the bottle-service scandal involved a cigarette vending machine in a campus restaurant. His then-roommate, Christopher Ashby, says that midway through the campaign, a stack of “B.C.” matchbooks mysteriously appeared inside the machine, causing a ruckus about Clinton’s spending. Ashby says the cost was irrelevant because the campaign had nothing to do with it—they didn’t buy the matchbooks or stock the machine, and they never found out who did. It’s almost like Clinton had a PAC.

Next, Modglin remembers Clinton’s people tearing down his signs and throwing them into the Potomac (though Clinton’s autobiography claims the reverse). Ashby’s recollection is more nebulous. “Part of the hoopla,” he says, “is that it seemed to be happening to everybody.” Regardless, Modglin had his people rove the campus “talking up the fact that we were being essentially persecuted, we were being unfairly dealt with.” And when the votes came in, Clinton was toast. After years of Bill’s glad-handing, Ashby believes the campus suffered from a familiar affliction: “Clinton fatigue.”

Trifling student scandals do not signal the decline of democracy. But Modglin and Ashby do say that students’ relationship to government has changed. Back then, Georgetown took student government seriously. “We regarded our democratic process as something to revere and elections as something that were indicative of our country,” Modglin says. “People still trusted government, and people wanted to be leaders in government. Student government was considered a training ground for that.”

The class of 1968 alone produced three world leaders: Clinton as well as presidents of El Salvador and the Philippines. It’s an august lineage—one that weighed heavily as the 2022 election took an uglier turn.

Grads in Government

Georgetown University has spawned many a politico—including these famous alums

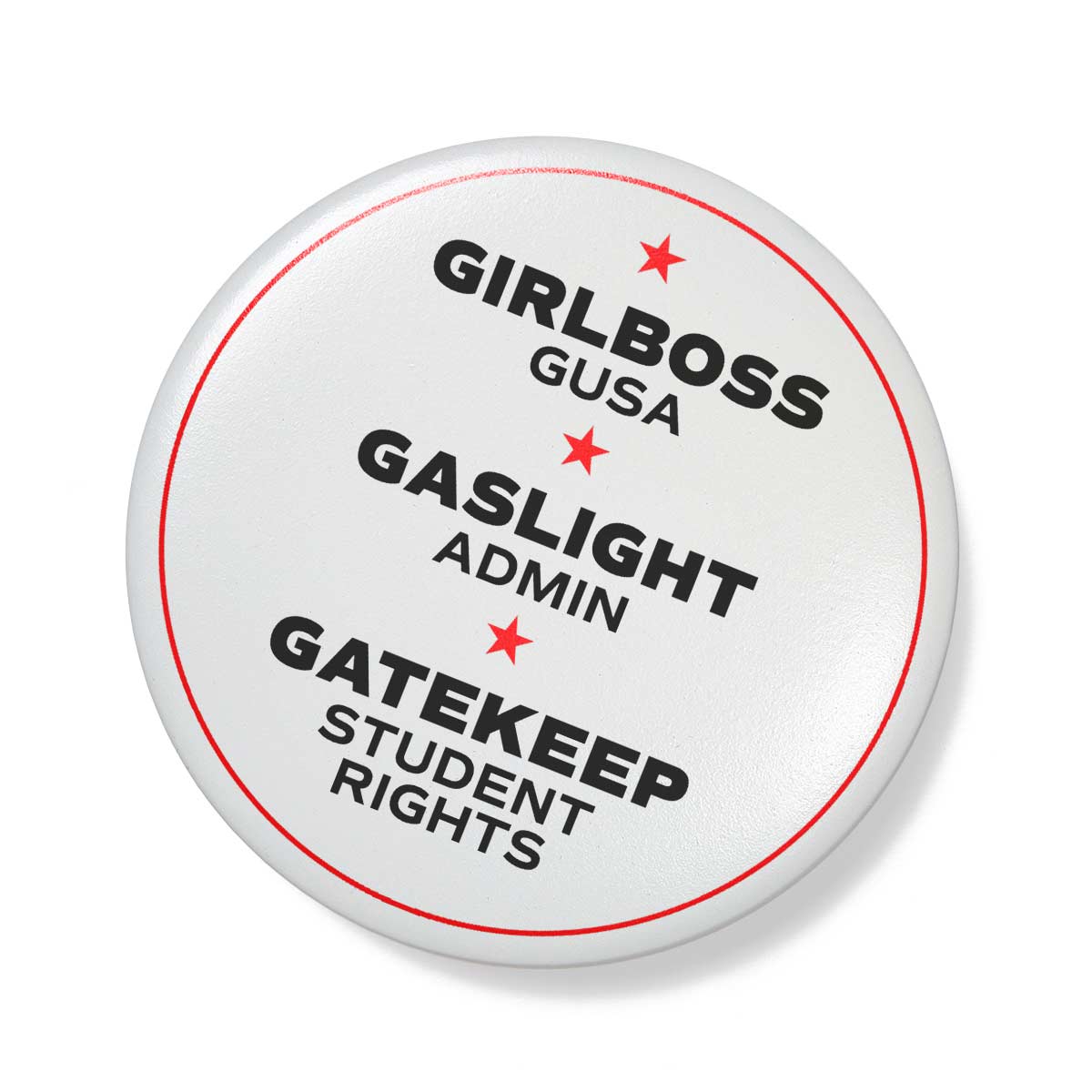

Ron Klain

Class of 1983. A longtime Biden adviser and current White House chief of staff, Klain was a government major. He has sometimes taught classes in the subject at his alma mater.

Antonin Scalia

Class of 1957. The late Supreme Court justice majored in history at Georgetown and was valedictorian of his class. He also studied abroad in Switzerland and was an enthusiastic member of the drama club.

Jon Ossoff

Class of 2009. The nation’s youngest sitting senator, Ossoff studied culture and politics in the School of Foreign Service. He sang a cappella in the Georgetown Chimes and interned on the Hill.

Kayleigh McEnany

Class of 2010. A former press secretary for President Trump, McEnany majored in international politics in the School of Foreign Service and also studied abroad at Oxford.

Pramila Jayapal

Class of 1986. Leader of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, Jayapal came to Georgetown to study English lit at age 16. She’s the first Indian American woman to serve in Congress.

Lisa Murkowski

Class of 1980. Now a powerful swing vote in the Senate, Murkowski studied economics as an undergraduate and also won the “Funniest Human at Georgetown” competition.

Imagine you’re at the dining hall and this is what you’re hearing: Kole and Zeke are alt-right. They’re known campus conservatives, right-wing provocateurs running simply to sow division. As Trump acolytes, they took money from Turning Point USA, that unsavory bunch of young MAGAs yanking campus culture to the right.

From these whispers, you might conclude that this isn’t an ordinary student election, a sleepy debate over textbook costs and campus mental health. It’s more like a battle for the soul of Georgetown, an ugly local skirmish in the nation’s unending partisan war. To Alexandra Bowman, “it all so closely mirrored the national situation that I did feel like Kole and Zeke could win.” Around this time—maybe a week before the election—she remembers “a real concern in the air that people needed to turn out to vote.”

But vote for which ticket? The frat bros were anathema, and supporting the insiders, as one student said, would be “like voting for Joe Biden, but worse.” Even the Hoya—Georgetown’s storied student paper—was torn. In issuing its coveted endorsement, the publication punted, asking students to “reject both options for GUSA executive” and write in a credible alternative. This was six days before voting began.

The students following GUSA were now in a collective meltdown. “Some people I know were actually considering voting for Kole and Zeke to just blow up the whole electoral system,” says Darren Jian, the student reporter. “The thought process was that it would accelerate the decline of GUSA, that Kole and Zeke would run it into the ground to the point where a new student government would be needed.” For similar reasons, Josh considered writing in Emperor Palpatine. “I was just kind of done with it all,” he says.

But beneath this frenzy was a baseline assumption: that the establishment ticket would win. If the Hoya actually believed the race was close, then surely it would have endorsed Thomas and Nirvana, whom it tepidly labeled “the more promising of the two options.” But that quasi-non-endorsement was easy to miss amid the paper’s copious handwringing over Hillary’s emails—whoops, I mean Thomas and Nirvana’s flaws.

This is the point in the movie when you start shouting at the screen. But the Georgetown kids can’t hear you. And as voters flocked to Kole and Zeke—younger students, first-time voters, kids who’d never been adjacent to GUSA before—few noticed. “They slipped under the radar,” says Nile Blass, the outgoing president of GUSA, “because nobody took them seriously, because they were so below critique.”

Kole and Zeke learned of their victory by email, at 3:30 in the morning, while walking to their dorm after grabbing wings. “Honestly, at that point we were just done with the whole situation and we would have taken whatever result in stride,” Zeke says.

“And we barely won,” Kole adds. “We backdoored it off, like, a few votes.” It was 34, to be exact.

Actually, the winner of the most first choice votes was a different ticket entirely: juniors Marcella Wiggan and Otice Carder. Just days before, they’d emerged to save GUSA from the squabbling insiders and the chaotic outsiders, and their progressive write-in bid nearly worked. But Georgetown uses ranked-choice voting, and the result flipped as second and third choices were tallied. To some, Marcella and Otice lost the race despite winning the popular vote. “It is the Trump election,” Nile Blass says. “The silly sleeper cell beat the Bernie campaign and the Hillary campaign.”

But if Kole and Zeke’s triumph was 2016, then the aftermath was pure 2020: a crisis over whether to certify the results. Just hours after the polls closed, a bombshell landed in the Election Commission’s inbox: an allegation that Kole and Zeke had traded booze for votes. Bizarrely, this came through an encrypted Swiss email service—and when reached on another platform, the student who appeared to have sent it hadn’t an inkling of what had occurred. Shortly after, a second allegation arrived, this one from the rival campaign.

The previous evening, Marcella and Otice apparently heard from three students—two of whom were making out—that they’d voted for Kole and Zeke in exchange for beer. If true, this would be disqualifying. But Kole and Zeke flatly denied the allegations, Otice’s account was hearsay, and the prior fraudulent email cast the whole situation in a bewildering light. When they appeared on Zoom before the GUSA Senate, the exhausted student volunteers on the Election Commission bowed out, asking the senators to figure it out for themselves.

As the senators debated whether to certify, frustrated students began spamming the chat. “They were shitposting,” Darren Jian says, “just saying random stuff, making jokes, saying GUSA was staging an insurrection.” Someone projected a meme of SpongeBob with an erection. Eventually, the speaker of the Senate had to mute everyone for debate to proceed. Some senators opposed certifying due to the allegations, others because they found Kole and Zeke personally objectionable. Another faction thought they should certify because nobody disputed the integrity of the vote itself.

The election finally ended when one of the senators brokered a deal: The Senate would certify, but in exchange, it would launch an impeachment inquiry against Kole and Zeke—that way, GUSA could dig further into the beer-for-votes story. “It felt a little bit theatrical,” Alexandra Bowman says, “like people just didn’t want them to win, so they set up an impeachment. It was an unfortunate happenstance. It was exhausting and it felt stupid.”

“Exhausting and stupid” was basically the vibe on campus the following month when, after the impeachment inquiry came up empty, Kole and Zeke were sworn in.

So is GUSA a frat house now? Have funds for disabled students been diverted to club lacrosse?

Well, no. Things have actually been pretty normal since Kole and Zeke took office. They’ve continued the transformative initiatives of the previous administration—the ones so lauded for helping marginalized groups—and they’re running some projects of their own: expanding dining options, for example, and negotiating free student access to various newspapers. “It’s nothing groundbreaking,” says Bora Balçay, a longtime senator who, despite not voting for them, is now Kole and Zeke’s chief of staff. “But I mean, it’s business as usual. The day-to-day is getting done.”

It’s late August when I finally meet Kole, who is moving back into his dorm. Freshman convocation has just let out, and as GUSA president, he played a ceremonial role. “I had to wear a robe and pass someone a flag,” he says, “but I don’t think they really needed me.” The quad is aswirl in freshmen and their families, clotting the walkways in suits and summer dresses, sweating off their makeup in the heat. Kole tosses his black robe over his shoulder and steers us toward the Georgetown waterfront. It’s quieter there, he says.

As we pass frothing water sculptures and oysters on the half shell, Kole begins venting about Kyrsten Sinema’s ties to private equity, about special interests blocking the corporate minimum tax and—Sorry, what? Don’t you support Trump? He bristles, telling me that his personal politics shouldn’t be relevant to student government, but for the record, he’s a Bernie guy. Baffled, I ask why he didn’t just say something. Well, his campaign time was limited and he wasn’t going to spend it knocking down rumors.

For a moment, my brain shreds: This whole ludicrous election was a misunderstanding? A mudslide of partisan catastrophizing that could have been cleared up with a tweet? But actually, Kole is right—the narrative was too powerful to change. Before I met him, I talked to some of his supporters, who told me outright that they weren’t Trumpy and didn’t think Kole was, either. They claimed to back him for boring reasons, like his snooze of a campaign promise to overhaul Georgetown’s club website. But did I believe them? Not really. It’s safer to be skeptical—even kids can be cryptofascists these days.

Like me, the folks in GUSA expected Kole to be dopey and malevolent. But during the transition, when he kept showing up, asking questions, doing his best, he says the stigma mostly fell away. Was he the most qualified candidate? No. The most socially minded? Not by far. But he actually seems to care about governing; he’d rather discuss his campus dining initiatives than whatever grievances still linger from the campaign. Kole is more focused than some of the grownups on Capitol Hill. If kids like him are our future leaders, then we might just be all right.

Rounding the bend by the kayak rentals, I ask what Kole will run for after college. He seems a little bewildered. “That’s not something I have plans to do,” he replies. He’s currently searching for his passion: The State Department sounds intriguing, and teaching history might be something to explore. Mostly, Kole wants to be happy. He’s about to start a one-credit Jesuit vocational course called “Personal Narratives,” to help him self-reflect and chart a path.

For an uncomfortable beat, I stare dead-eyed at the Potomac: Kole is a government major, the student president of Georgetown—if he’s not our future overlord, who is?

Bora Balçay later fills me in. “I know multiple people at Georgetown who are already planning their first congressional run, but they’re not in GUSA,” he says. These kids—the ones with stratospheric ambitions—flock to the campus wings of the national parties: the College Democrats and College Republicans, pipelines to campaign jobs and internships on the Hill.

Oh. So our future leaders are not in GUSA learning how to govern—they’re too busy becoming good partisans. Oh, dear. The next generation won’t save us from Washington. They’re already learning its ways.

Design by Connie Zheng.

This article appears in the October 2022 issue of Washingtonian.