With roughly 2,000 animals in the care of the National Zoo, dealing with the end of life is an inevitable part of the job, and these last few months saw several notable deaths.

Luke, a 17-year-old African lion, died on Oct. 19; Naba, an 18-year-old African lion, died on Sept. 26; and Calli, a 17-year-old California sea lion, died on Sept. 7. While counts obviously ebb and flow year by year, the zoo (using data from the past three years and including small animals like fish) estimates that it loses about 200 animals annually.

But while we get to see how the critters celebrate their birthdays and even holidays (hint: it often involves elaborate species-friendly treats), their deaths are more of a mystery. Is there a funeral? A secret animal graveyard somewhere?

Well, no and no.

While zookeepers are human and certainly mourn the loss of their “coworkers”—the zoo even maintains a relationship with a local animal grief counselor—they are also biologists. And in death, there’s a window for research.

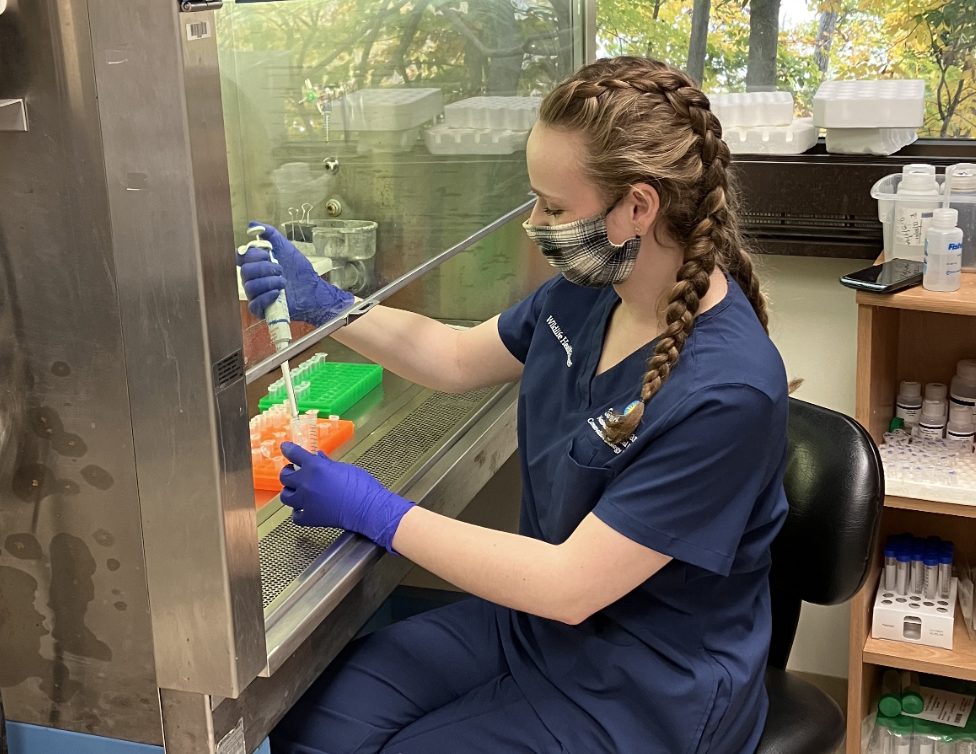

Consequently, just about every animal that dies in the care of the zoo, whether from euthanasia or on its own, is immediately sent to the zoo’s pathology lab for a necropsy—the equivalent of a human autopsy.

“All organs are evaluated, all joints are evaluated, diagnostic samples are taken, maybe even beyond what we took when the animal was alive,” says Don Neiffer, chief veterinarian for the National Zoo. “The samples are then frozen for future evaluation and research that could benefit conservation. Tissues also go out for something called histopathology,” or the microscopic study of disease.

According to Neiffer, the zoo has tissue samples of nearly every animal there since the ’70s—including a few species that are now extinct.

Any resulting information is then shared across the industry, providing useful data to researchers who may be studying a niche health issue within a certain species that they normally wouldn’t have access to. “In death, we utilize these animals to help improve the lives for the others they left behind,” says Neiffer.

For example, when the first baby Asian elephant born at the zoo unexpectedly died in 1995, its necropsy led to the discovery of a previously unidentified herpesvirus in elephants. “Basically, it was the wellspring for elephant herpes virus research, diagnostics, treatment, and hopefully an eventual cure,” says Neiffer.

Even local wildlife, like squirrels that wander onto the zoo’s campus and die, undergo necropsies.

“Because of our collection, we want to do surveillance,” said Neiffer. “If [dead wildlife] comes to us, we do at least minimal gross dissection, but oftentimes we do diagnostics. We’re looking at any issues that could concern our team or animals,” such as rabies or Avian influenza. Likewise, the zoo shares this data with local wildlife departments.

Afterward, leftover parts of the animal—think a shell from a tortoise or the skeleton of a cheetah—might go to a museum or education center. In fact, the National Museum of Natural History has several skeletons from the zoo in its collection.

Anything remaining will be cremated, including even the tiniest of animals. “Everything from guppies to elephants is incinerated,” says Neiffer.

While burials were once commonplace at zoos, very few bury their animals anymore. One reason for that: “You don’t want illicit wildlife parts ending up in anybody’s hands,” says Neiffer.

Of course, underlying all these scientific processes is the emotional side of death, too. “Anyone who has a good understanding of how much we love these animals and care for them can understand how difficult end of life care is,” says Brandie Smith, the zoo’s director. “But also, these are professionals. These are people who train their entire career to do this.”

With so many of the animals living past their species’ mortality rates in the wild, the zoo’s workers must regularly confront a heart-wrenching question: if and when to euthanize a terminally ill animal. The zoo keeps a detailed chart, tracking the animal’s quality of life‚ marking whether it’s still eating, staying active, and socializing. When it becomes clear that the “animal is suffering beyond what’s reasonable,” then it’s time.

“It’s hard on us, but we take on that burden as zookeepers,” says Neiffer. “It’s our onus and our responsibility to provide the animals with that peaceful passage to the next plane. When we can remove [their suffering], we’ve given them that last gift.”

Still, it’s always hard to say goodbye, which is why the zoo provides its keepers a final moment with the animal before euthanasia. Even particularly social species, like elephants and great apes, receive a moment to acknowledge the death of their habitat mate (assuming it died from a noninfectious cause).

While there’s ultimately no funeral or ceremony, there are sympathy cards. The public often sends in memories they had of an animal, drawings from children, and well wishes for staff, says Smith. In the case of a panda cub that lived only for a few days, Smith says “the outpouring of sympathy and grief from the public was really powerful.”

Then, as with all things, life goes on.

“Animal keepers as a whole are an incredibly stoic group of people and they’re good at grieving with one another—but they also have a job to do,” says Smith. “There are other animals to take care of. It’s part of the cycle they have been trained for.”