Abdul Muzikir carried a Remington 12-gauge shotgun under his coat as he entered the District Building at 2:30 PM on March 9, 1977. Abdul Nuh, a fellow member of DC’s Hanafi Muslim sect, toted a machete. The two men climbed the stairs to the fifth floor, where they took a police officer hostage and ordered everyone they saw to hit the ground.

Soon after, DC Council member Marion Barry returned to the building from an event he’d attended. In the lobby, a security guard named Mack Cantrell told him there seemed to be some trouble on the fifth floor and offered to ride up with him on the elevator. When they got to the council’s offices, Muzikir was there with his shotgun out. He fired a single blast, which struck Cantrell in the face. Barry was hit in the chest, and a reporter for WHUR named Maurice Williams, who was also on the scene, got shot as well. Barry would recover, but Williams was declared dead when he arrived at the hospital. Cantrell died months later, most likely due to lingering effects of the shooting.

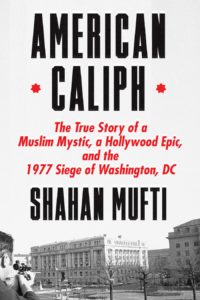

Those terrifying events are the subject of a new book, American Caliph: The True Story of a Muslim Mystic, a Hollywood Epic, and the 1977 Siege of Washington, DC. Written by journalist Shahan Mufti, it sheds light on an incident that was big news at the time but, 45 years later, has to some extent faded from memory. The story of the siege is well worth telling, though, as it touches on lots of facets of modern Washington, including political violence, policing, media, and the quest for DC statehood.

The District Building wasn’t the only site of the attack. Over the course of three days, Hanafi members occupied two other buildings: the Rhode Island Avenue, Northwest, headquarters of the Jewish service organization B’nai Brith and the Islamic Center on Embassy Row. The Hanafis’ leader, a former jazz drummer named Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, claimed that the goal was to stop the showing of a biopic about the Prophet Muhammad scheduled to take place in New York City. But he had other demands, rooted in the horrific murder of seven of his children and grandchildren at the Hanafis’ house on 16th Street, Northwest, four years earlier. (Several members of the rival Nation of Islam were convicted of the killings.)

Mufti, a journalism professor at the University of Richmond, spent more than six years on American Caliph. He grew interested in the subject of political Islam while working as a reporter in Pakistan, where his parents are from. (He was raised both there and in the US.) When he learned about the siege, he saw echoes of struggles he’d encountered elsewhere in the Muslim world.

But the Hanafis—along with the siege itself—were a fascinating subject even without the global resonances. Mufti immersed himself in the story, tracking down a number of primary sources, including former DC police chief Maurice Cullinane and several of the Hanafis. His reporting persistence led to some valuable finds: One person he interviewed had 15 volumes of court transcripts getting damp in his garage. A former hostage had written a book proposal, which Mufti found among an agent’s papers that had been deposited at the Library of Congress. Combined with contemporaneous news accounts and the available court records (though many have been lost, frustratingly), Mufti’s efforts add up to the most complete picture yet of what happened—and why it mattered.

Much of American Caliph explores the leadership struggle inside America’s Muslim community as the faith gained popularity in the 1970s, with a large infusion of Black converts—Khaalis’s aspirations on that front were apparently a motivating factor in the siege. “He did get close to being the most famous Muslim in the United States,” says Mufti. “I mean, it was working for a wild minute there.”

But the author also digs into how Khaalis’s hunger for media attention fueled the violence. The siege was directly inspired by the heavily covered 1972 attack at the Munich Olympics, when Palestinian gunmen murdered 11 Israeli athletes. Mufti says the lesson was clear to Khaalis: “If you take downtown Washington, the cameras are going to come.”

My dad’s been taken hostage by some crazed religious gunmen,” David Simon told his teacher. “I gotta go.

David Simon was a junior at Bethesda–Chevy Chase High School in 1977, and one day while he was at work in the office of the Tattler, B-CC’s student newspaper, he got a call from his sister. She told him to turn on the office’s small TV. Something was happening at their dad’s office.

Flicking on the set, Simon saw that seven gunmen had taken over the headquarters of B’nai Brith, where his father, Bernard, was the director of communications. Simon was pretty sure his father was among the 100 or so hostages being held in the building. Simon headed to his sixth-period English class, where he recalls telling the substitute teacher, “My dad’s been taken hostage by some crazed religious gunmen and I gotta go.”

Simon and his sister soon joined other members of their family at a church across Scott Circle from B’nai Brith’s headquarters. At that point, it was just becoming clear that something big was unfolding. “We figured out in a relatively short time that all three locations were connected,” says Pat Collins, who was then working for Channel 9 and was one of the first journalists to arrive at the Islamic Center. Reporters across the city began to fan out to all three sites. The local TV channels broke into their regular programming, covering the developing terror attack from live trucks—a recent innovation that made it possible to broadcast from the scene.

One of the media’s best sources for what was going on was Khaalis, who was holed up inside the Anti-Defamation League’s offices in B’nai Brith. The Hanafi leader spent the siege working the phones around the clock, alternating between conversations with police and a growing mass of local, national, and international press. “He never slept, which was part of the problem,” says Mufti. “He was slowly disintegrating mentally.”

The police set up a command center at the Holiday Inn across from B’nai Brith. At that point, it seemed quite possible that things would end very badly. “It was almost like you had three war zones going,” Collins recalls. “It was something we had never dealt with before. This could have really been tragic. He had the men and the weapons and the capability to have a bloodbath. This could have been a mass tragedy in our city.”

The situation was complicated by jurisdictional issues. Should local police or federal law enforcement lead the response? DC had gained home rule less than four years earlier, and the situation quickly turned into a test of its self-governance. President Carter was reluctant to get involved, but in the book Mufti reports that the administration prepared an executive order that would give the US military a green light to take control of the city, if necessary. Though DC police ended up in charge, it was clear that the city’s newfound political power could still vanish at any moment.

It was like you had three war zones,” says Pat Collins. “It was something we had never dealt with before.

The siege finally came to an end thanks to the intervention of diplomats from Egypt, Iran, and Pakistan, who met with Khaalis in B’nai Brith’s lobby and convinced him to release the hostages. He and 11 other Hanafi hostage-takers were arrested and charged with murder, armed kidnapping, and conspiracy, among many other things. Khaalis was convicted on the conspiracy charge, which opened him to convictions for crimes at all three locations, and sentenced to a minimum of 41 years in prison. He died in federal prison in North Carolina in 2003. The others were convicted of various crimes as well.

David Simon’s dad, who ended up being unharmed during his 39 hours of captivity, testified at the trial. He had formed something of a bond with Abdul Hamid, one of the gunmen who seemed remorseful during the siege. Bernard Simon “understood that these guys were trying to find their way back to normative Islam,” says Simon, who went on to become a newspaper journalist and then creator of HBO shows such as The Wire and We Own This City. “My dad was not angry; he definitely had PTSD, and he was sad.”

Abdul Muzikir, the man who shot the people in the District Building, was convicted of second-degree murder, armed kidnapping, and assault with the intent to kill and was sentenced to a minimum of 77 years in prison. This past spring, he was granted compassionate release after spending 44 years in prison. He now lives in Silver Spring. Mufti says he tried repeatedly to interview him for the book; Muzikir declined. The Hanafis still occupy that same building on 16th Street, and Mufti attempted to talk to the handful of people who continue to live there. “They didn’t speak to me—nobody in that house,” he says. “They’re not interested.”

Today we’ve unfortunately grown accustomed to the threat of political violence, but back then the siege felt like something new in DC. “I really think that was the first act of terror in the city of Washington,” says Collins. Khaalis himself seems to have come to regret the attacks he orchestrated. As Mufti’s book reports, the Hanafi leader wrote to Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini from prison in 1979, asking him to free the American hostages that were being held at Tehran’s US Embassy. “If this is not resolved peacefully, it would be disastrous for both sides,” Khaalis wrote. “There will be no winner at all. Believe me, I know.”

This article appears in the November 2022 issue of Washingtonian.