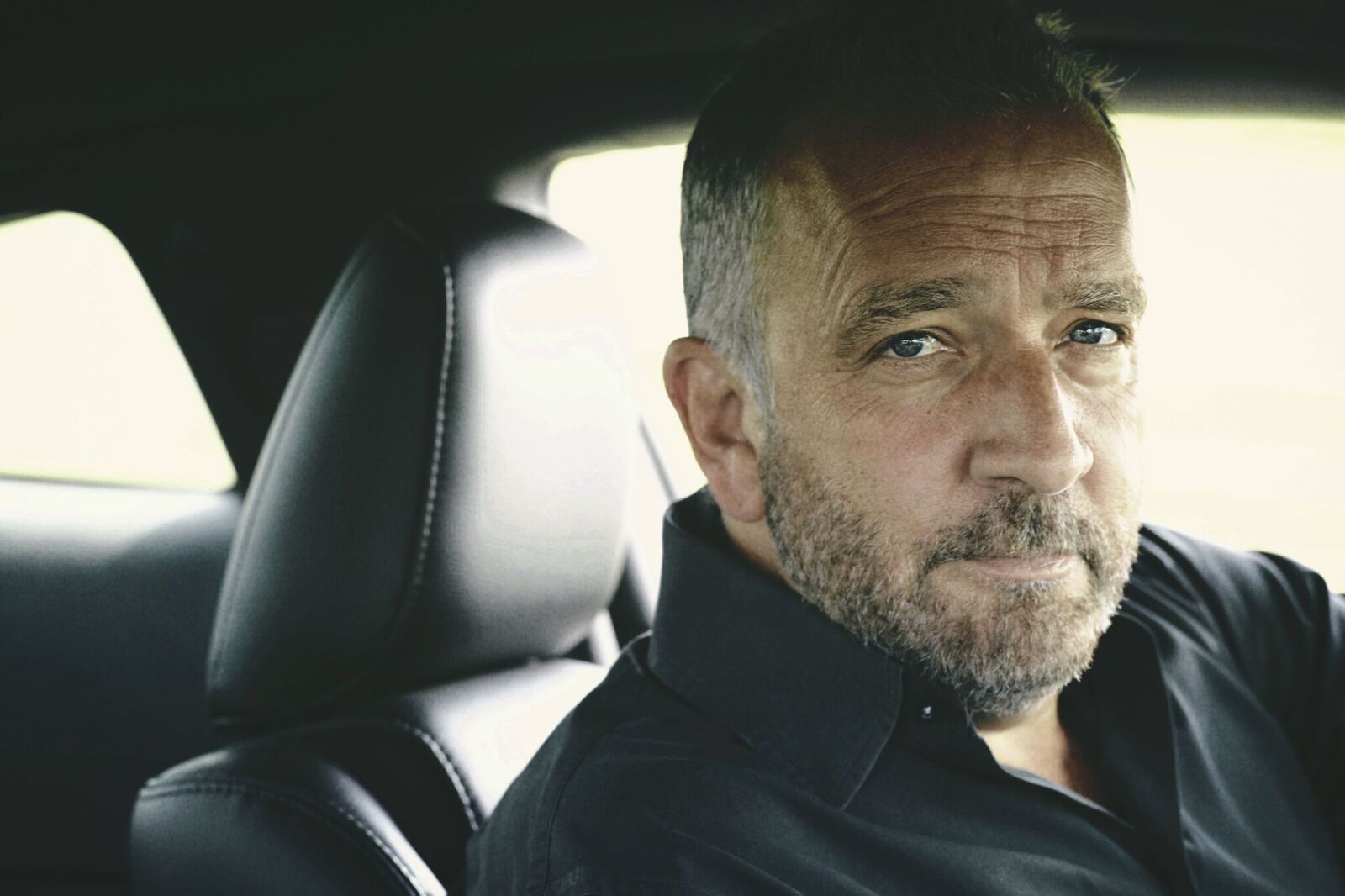

George Pelecanos, screenwriter for The Wire and author of 21 crime novels, is launching a film festival tomorrow, February 3 at Silver Spring’s AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center. “George Pelecanos Presents,” which runs through April 23, features eight low-budget films from the 1970s including Coffy, Rolling Thunder, and Walking Tall.

Pelecanos, who grew up in Silver Spring and has a film degree from University of Maryland, will be on hand at certain screenings to introduce the films, but first, we caught up with him to talk movie history, his more recent favorites, and the Oscars.

You’ve put together film festivals before. What is it about organizing them that you like?

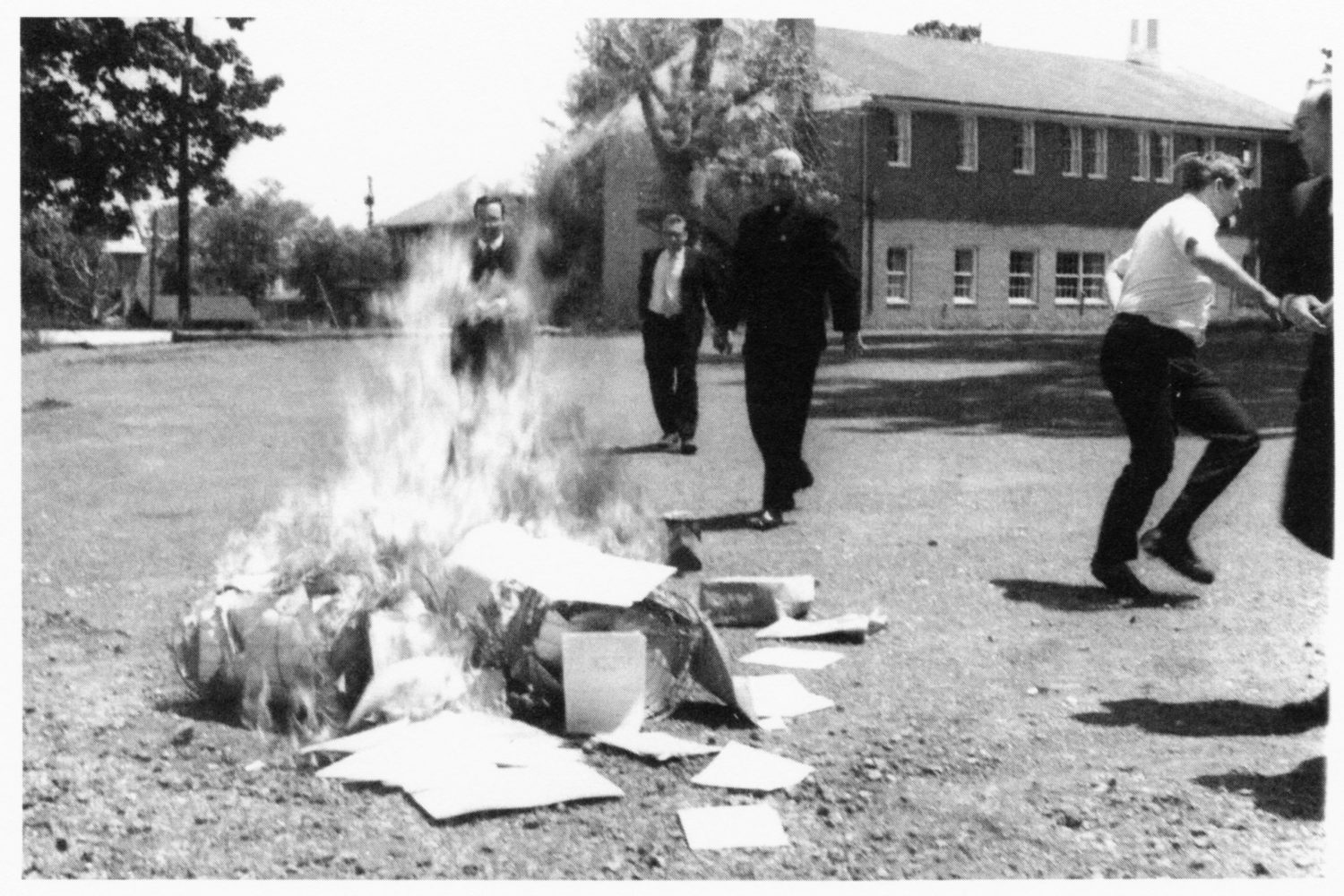

I just like screening these films for people that might not have seen them yet. None of these films were up for any Academy Awards, and in terms of the ‘70s, they’re not in the same league as the films of Scorsese, or Hal Ashby, or Coppola. But they have their place in film history, and they’re often neglected. All of these films share something in common: they were meant to be seen communally, with an audience. You don’t get the same impact watching these in your living room.

What do you think it is about the communal aspect of movie-watching that makes it so different?

It feeds the fire. If you’ve ever seen a comedy, for example, like Blazing Saddles, where the laughter is infectious, it enhances the experience.

These films were made for the South only, for the Southern circuit. [Walking Tall] opened very quietly and then caught fire around the country. Audiences all over the country were standing up and applauding for this film. Seven-Ups is a movie I couldn’t fit in [to the festival]. It has a car chase in it—one of the best car chases in modern film. I saw that film three times in the theaters, and every time, people were standing up out of their seats and clapping. You do not get that at home.

What do you mean these films were made for Southern audiences?

The characters in these films were related to the audience they were shooting for. Blaxploitation films were made for urban audiences. Walking Tall was made for Southerners. Most American movies aren’t made that way. They’re made for general audiences. But these films were made for the people who came to see them, and that’s one of the things that sets them apart.

What audiences were some of the other films made for?

A movie like Car Wash? Anybody who had a job like that—it didn’t have to be working in a car wash. You could be working retail, you could be working in a restaurant. Whoever has been under the thumb of a boss, in a low-paying job. When that film came out, the title song was a huge smash. And people—I did it too, I was working in retail—went back to their jobs and took the lyrics and changed them to their particular job. It became this phenomenon across the country.

Why did you choose this particular era of films, the 1970s?

As the decade came [to a] close, movies changed. Actually, the movies in the middle of the decade—you had Jaws and Star Wars in ’75 and ’77, respectively—the whole business changed after that. Studios weren’t interested in making smaller films. They were all trying to hit a grand slam. And by the time the decade turned, video came around, and these kinds of films were made direct video, they weren’t made for theaters anymore. It was really the end of an era.

How did you narrow it down to these eight movies?

These are all films that I have real affection for, in various ways. They’re not perfect. I can recognize the flaws. But the cool thing about low-budget films is that the audience forgives a lot. They’re there to have fun. Coffy was made for probably $400,000, and people were lined up around the block to see that film. Black audiences wanted to see themselves represented on screen really for the first time, not in the Sidney Poitier kind of way, not in that noble way, but in the “I’m standing tall” kind of way.

There’s a scene in that movie where Pam Grier is being chased. And the reason she’s limping is she broke her foot while making the movie. And they put a cast on her foot and painted it to look like a shoe.

Have films impacted your writing?

Movies are where I learned my story. It wasn’t books—I didn’t start reading books or novels until I was in college. When I was young, I lived in the city, in Mount Pleasant, but we moved to Silver Spring. I was one of those kids who would take the bus downtown and find these movies that I wanted to see because they didn’t come out to the suburbs. Blaxploitation, kung fu, slasher films. All these psychotronic films I wanted to see.

And it has made its way into my books. There’s the story structure. When I’m writing, I see a movie in my head. I even listen to movie music when I’m writing—a lot of Ennio Morricone and Lalo Schifrin, Jerry Fielding. It helps me set the tone of my scenes.

Any thoughts on the current Oscar nominations?

I don’t really care. The two films I like the most this year were Tár and Banshees however you say it. I get all the movies from the Academy, they send me DVDs.

Tár is just incredible film-making, in the league of Kubrick and the French New Wave. It’s the kind of movie you don’t see anymore, and the kind of film that stays with you for days. There’s people that hate that film and that’s great. It promotes argument. It means it did something. It moved people in a certain way. Not in an entirely positive way, but it did something instead of just laying there like a bagel.

Banshees [of Inisherin] was Shakespearean. The writing was supurb. And the acting. Only that guy [Martin] McDonagh could have written that film. That’s an artist.

How do you feel about American cinema today?

I never say I hate something. It’s more like it’s not to my taste. Comic book films, I don’t watch them. There’s nothing about them that interest me. But those are the films the studios want to make. If you look at the grosses, there’s a reason for that. Unfortunately it’s come at a cost to filmmakers who are trying to do something cinematic and serious.

Scorsese got a lot of flack for saying comic book movies are not cinema, but they’re not. It’s just entertainment. It’s a roller coaster. It all really goes back to what I said about Jaws and Star Wars. That’s what changed everything. The Blaxploitation thing only lasted a few years, and then it dried up for all these people that were actors and crew and all that stuff. Pam Grier, who was a superstar for a time, didn’t work for a long time.

Why did you choose to show the films at AFI Silver?

The Silver Theater was the theater of my childhood. I used to go with my dad. I saw The Exorcist there at a packed house.

Any favorite DC movies?

Not a lot of films are shot in Washington. I’m one of the only people who ever did that. I made a movie called DC Noir a bunch of years ago that was 100 percent shot in the District based on my short stories. They’re doing a show called Cross based on the James Patterson novels, and they shot two days in Washington for the monuments and all that. Now they’re going up to Toronto to make the series. House of Cards was in Washington, shot in Baltimore.

This interview has been condensed for clarity and length.