At noon on a steamy summer day in 1950, a small crowd gathered in front of the District Building in Washington, DC, for a ceremony marking the presentation of an odd gift to the city. On the stairs was a group of middle-aged bureaucrats in loose-fitting suits—not an unusual sight in the District—along with something far less expected: an enormous copper bell in a wooden yoke. To any passersby, it would have looked both instantly familiar and completely out of place in the entranceway of the city’s municipal offices. This was a full-size replica of Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell, albeit with the famous crack painted on.

The Treasury Department had commissioned scores of these replicas from a foundry in France to advertise a US savings-bond drive. Throughout the spring of 1950, the bells toured the country. One was then given as a thank-you to each of the states and territories.

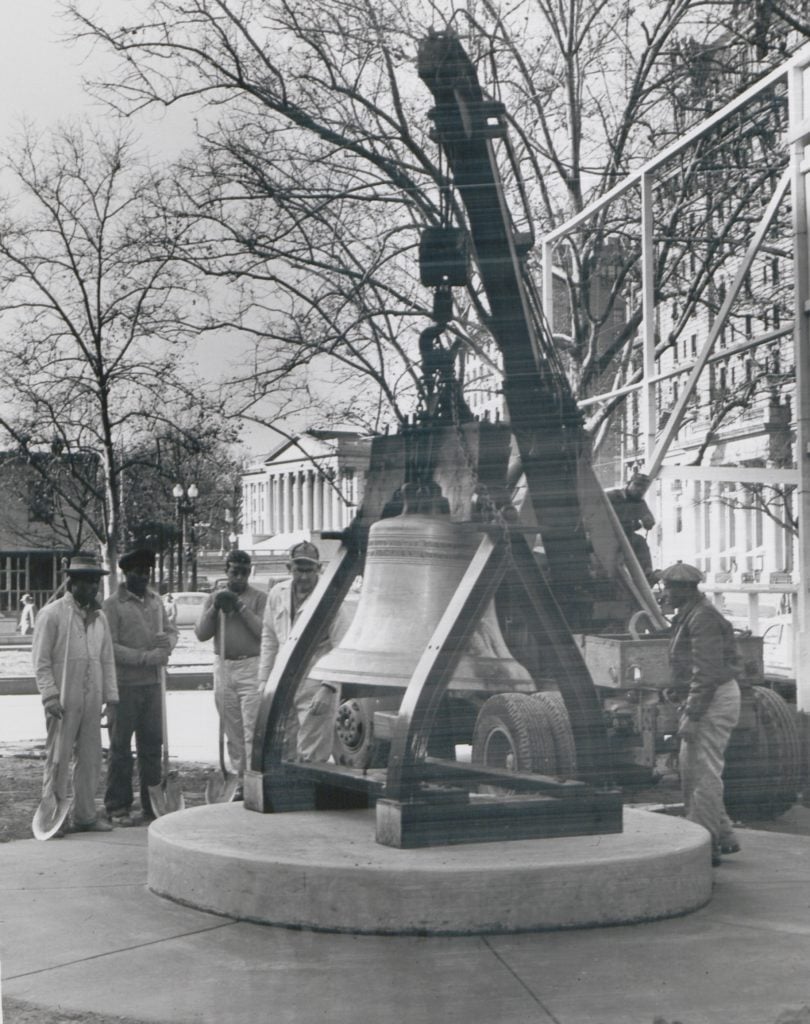

They were unwieldy gifts. In DC, no one really knew what to do with the thing. In its initial spot at the top of the District Building stairs, the bell was kind of in the way. The location was meant to be temporary, but it would be another five years before anyone got around to moving the heavy object. And when they did, it was just 100 feet or so across the street, to a crowded traffic triangle formed by the intersection of 14th Street, E Street, and Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest. It still looked out of place, critics complained. A few months later, in the fall of 1955, DC’s Board of Commissioners voted—without much enthusiasm—on a permanent location a few feet farther east in the same triangle.

But over the decades, the Liberty Bell replica that no one had seemed to want became a local landmark of sorts. It was an easy rendezvous spot for some: “I’ll meet you at the bell.” It occasionally served as a patriotic backdrop—Miss Washington 1956 was photographed there—and residents sometimes rang the bell in celebration as parades passed on Pennsylvania Avenue.

And then, sometime between October 1979 and July 1981, the 2,080-pound symbol of freedom simply vanished.

The first time Josh Gibson saw this DC Liberty Bell was in an old photograph depicting a long-forgotten 1960 celebration of “Friendship With Holland Day.” The foreground of the image is dominated by a woman in a towering Dutch bonnet, but behind her is the unmistakable silhouette of one of the country’s most famous objects. At the time, seven or eight years ago, Gibson had recently gotten a job as the DC Council’s director of communications, and in addition to his regular duties, he had taken on the task of locating historic objects in the Wilson Building (as the District Building has been known since 1994). The black-and-white Holland Day image was one of the things he was curious about—especially after he noticed the background. What was this Liberty Bell doing in DC? And where did it go?

As Gibson soon learned through his research, the bell’s home in the traffic triangle hadn’t been as permanent as the commissioners intended. By the late 1970s, the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation was making plans to build the public space now known as Freedom Plaza. The bell—as well as a 30-foot oak tree that had been a gift from France and a statue of Alexander “Boss” Shepherd that shared the space—had to be moved to make room for a rerouted Pennsylvania Avenue. There’s no evidence that they considered scrapping the bell, but it also wasn’t a key part of the renovations. According to plans archived by the National Capital Planning Commission, it could be “a minor focal point anywhere.”

But here’s where things get fuzzy. As work on the project began in 1979, both the bell and the Boss Shepherd statue were temporarily relocated to a construction site near Fourth and Pennsylvania.

Then the trail goes dark: The last evidence Gibson has uncovered about the bell’s whereabouts is in a late-1979 Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation document noting that the DC government needed to move both items from that location within weeks. Construction would soon begin on the new Canadian Embassy. Clearly, that happened—the embassy is now there, while the bell is not. In 1981, a Washington Post reporter discovered the Boss Shepherd statue lying in the weeds at the Blue Plains Sewage Treatment Plant. The bell wasn’t with it, however. It has never been spotted since.

“That is not the bell,” Josh Gibson says when I meet him in the atrium of the Wilson Building. He gestures to a six-foot-tall red-green-and-gold bell given to DC in 1963 by the city of Bangkok. That settled, he leads me into his office, which is filled with evidence of his penchant for local history. There’s a preretrocession map that shows the District as a diamond; a poster of John A. Wilson, the building’s namesake; autographs from Chuck Brown and Cool “Disco” Dan; and, yes, a (much smaller) replica of the Liberty Bell—a reference to his ongoing quest.

As Gibson explains while sitting at his cluttered desk, he has by now compiled quite a list of places where the 1950 DC Liberty Bell replica is not. It is not, for example, outside the west entrance of the Treasury Building. There is a faux Liberty Bell in that spot, but it turns out to be another replica that the Treasury ordered in 1950. It is also not in front of Union Station; that one—yet another Liberty Bell imitation—was donated to the US government by the American Legion in 1976 in honor of the Bicentennial. And it is not in Fort Lincoln Cemetery. Gibson received that promising lead from a local resident after first publicizing the mystery via a press conference in 2017. He rushed out to the site, just over the DC-Maryland border, where he found a full-size copy of the Liberty Bell. It had been cast at the same French foundry on the same mold as all the others produced in 1950—but, alas, it was commissioned a quarter century later. Another dead end.

In the course of his research, Gibson has investigated bells in cemeteries, public parks, campgrounds, and antiques markets. He’s toured little-used DC-government storage areas, tracked down former District and Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation employees, and scoured documents at the DC Archives, DC History Center, and National Archives. While on vacation in France in 2016, he even visited the foundry that produced the bells, which failed to turn up any useful leads.

How do you lose a massive bell? Well, this isn’t the first time such a thing has happened.

Probably by this point a question has occurred to you: How on earth do you lose a massive replica of the Liberty Bell? Well, as Gibson has now learned, this isn’t the only time such a thing has happened. In 1955, when the DC bell’s future location was a topic of debate, the Evening Star sent letters to the country’s governors asking what they had done with their similar one-ton gifts. An aide to the governor of Connecticut responded, “We do not have a record of having received such a memento.” They had; reporters found it at the state historical society in Hartford. Another bell, created by the same French foundry in 1950 for a private citizen, was discovered in the brush on an abandoned lot in Phoenix in 2004.

And in DC, other large historical artifacts have gone missing. Among them is Francis Scott Key’s home in Georgetown. Yes, an entire house: In 1947, the National Park Service carefully dismantled the structure to make way for the Whitehurst Freeway, with the intention of rebuilding it elsewhere. But that didn’t end up happening, and in 1981 it was revealed that the materials had been lost. Other missing objects include a limestone monument to the city’s last fire horse, which was erected somewhere in Blue Plains in the 1930s, and a large metal sphere that stood at the base of Meridian Hill Park from the 1930s until at least the 1970s, when it vanished after having been removed for repairs.

Every once in a while, though, a lost piece of history is found. The Boss Shepherd statue that was once discarded in the weeds at the water-treatment plant stands today in front of the Wilson Building, restored to its former glory. Will the missing Liberty Bell ever join it? Gibson isn’t giving up the search. Just a few weeks ago, he got a tip about a Liberty Bell copy that had arrived at a now-defunct bell museum in Quebec in 1980, about the same time that the District’s went missing. But close examination of a picture of that bell convinced Gibson that it, too, is not the bell. Gibson is also eager for access to records from the Canadian government related to the construction of its Washington embassy, where the bell was last seen. He’s been waiting three years to get the information he filed a request for.

But the disappointments haven’t stopped him from contemplating what the city should do with the bell if it’s ever found. Standing in front of the Wilson Building, he gestures toward the spot where the bell stood in the 1970s. “Selfishly, I would want it nearby so I could see it every time I came to the office,” he says. “But if it were in a neighborhood, it could be a landmark—a focal point. Here, downtown, it would always be the 578th-most interesting thing. That’s the sad ballad of the minor DC memorial.”

This article appears in the March 2022 issue of Washingtonian.