The District has a problem with holding risky and dangerous drivers accountable. That’s the key takeaway from a recent report in The Washington Post, which found that roughly 1,200 vehicles are linked to fines surpassing $20,000 over the last five years. And since 2000, over 6.2 million traffic tickets exceeding $1 billion have not been paid to DC.

According to the Post, many of these fines are for high-risk behaviors such as speeding and running red lights. In March, the driver of an SUV fleeing a traffic stop collided with a sedan on the Rock Creek Parkway, killing the sedan’s driver and two passengers; the SUV reportedly had 49 outstanding tickets with fines totaling $17,280.

Ryan Calder, an Assistant Professor of Environmental Health and Policy in the Department of Population Health Sciences at Virginia Tech, recently wrote a letter to Mayor Bowser, DC Council members, and department directors calling for legislative and executive action to reduce traffic deaths. There’s also an accompanying petition to garner public support.

Washingtonian spoke with Calder to better understand the role of traffic violations and enforcement in road safety for drivers and pedestrians:

How did you come to the topic of traffic safety?

I have a background in engineering, and a lot of my work revolves around the interaction between engineered systems and human health, and a lot of work around civil infrastructure and green energy transition. I was drawn into the traffic safety question in the wake of the Rock Creek Parkway crash, and I obviously was very concerned by that, started to learn more, and started to put thoughts to paper. I reached out to some local traffic safety groups, first DC Families for Safe Streets, and asked if this analysis I was putting together in letter form would be helpful for them. It seemed like a lot of the policies in DC had kind of broken down, and they were very receptive to my analysis, so we worked together to create a letter.

The SUV responsible for the Rock Creek Parkway crash was linked to over $17,000 in unpaid tickets. How do unpaid traffic tickets play a role in traffic safety?

It’s not so much a question of payment—it’s the fact that you’re establishing a record of previous violations, like excessive speeding, running red lights, and running stop signs. In DC, it has become about fines because this data is generated by the Automated Traffic Enforcement (ATE) [Editor’s note: traffic cameras that take photos of license plates but not vehicle occupants] that sends you tickets, so the most visible vehicles involved in this behavior are the ones that you can query online that haven’t paid their traffic fines.

In my opinion, the issue of payment or non-payment is almost separate from the fact that DC has all this data on people that are routinely going 25 miles over the speed limit and running red lights, and there’s no method of intervening in them.

Previously, non-payment of fines would have prevented you from renewing your license in DC, and that was abolished. The fines that we’re talking about, it’s not a $50 parking ticket; they’re people with tens of thousands of dollars. In one case, there’s a Maryland car with $186,000 in unpaid moving violations. At that level, it really is a public safety issue.

The petition calls to pursue reciprocity with Virginia and Maryland. What does that entail?

Currently, there are more boot-eligible cars registered outside of DC than there are DC cars in total. The vast majority of extreme offenders are cars registered outside of DC, and there’s no mechanism for those other states to use data supplied by DC to either prevent drivers from renewing their licenses until they’ve paid the fines or impound the cars.

The reciprocity negotiations would establish the mechanism by which other states enforce the fines that are issued by DC, and that’s already the case for moving violations. If you’re pulled over by a cop, and you get a written ticket, there is a mechanism between states to enforce payment, or at least resolution, of those cases. But that doesn’t exist for ATE.

The letter also opposes efforts to redirect revenue from ATE to fund road safety. Why?

Currently, the formula behind ATE is that it generates revenue for the city from people that speed and run red lights, and then the money raised from people paying those fines are used to fund traffic safety infrastructure. It was a closed-loop system of using reckless driving in order to improve traffic safety for everyone. In the proposed Mayor’s budget for the upcoming fiscal year, the mayor has proposed to redirect some of that money away from traffic safety into the general fund.

Since Vision Zero (the city’s goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2024) was adopted in 2015, traffic deaths in DC have been steadily increasing. We’re nowhere near zero and we’re going in the opposite direction. It seems like the wrong time to kind of redirect resources away from that initiative.

Traffic injuries and deaths disproportionately affect residents in Wards 7 and 8, where over 90 percent of the population is Black. How is DC addressing equity in their efforts to reduce traffic violence?

One of the things that I was so outraged by—and what kind of sparked my involvement—was the fact that various DC Council and executive offices in DC have cited equity in order to justify inaction on traffic violence.

They cited equity in order to not adopt an amendment to the Clean Hands Act of 2021 that would have prevented people with certain moving violations from renewing their licenses in order to preserve equitable access to driver’s licenses. It’s is a good goal, but it’s obviously exacerbating what I view as the bigger equity issue of the disproportionate number of lower-income and racialized people that are killed and seriously injured by reckless drivers.

The 2022 Vision Zero update frequently refers to enforcement as a critical component to improving safety, and ATE is the Department of Transportation’s biggest enforcement mechanism. How can enforcement work better to improve safety?

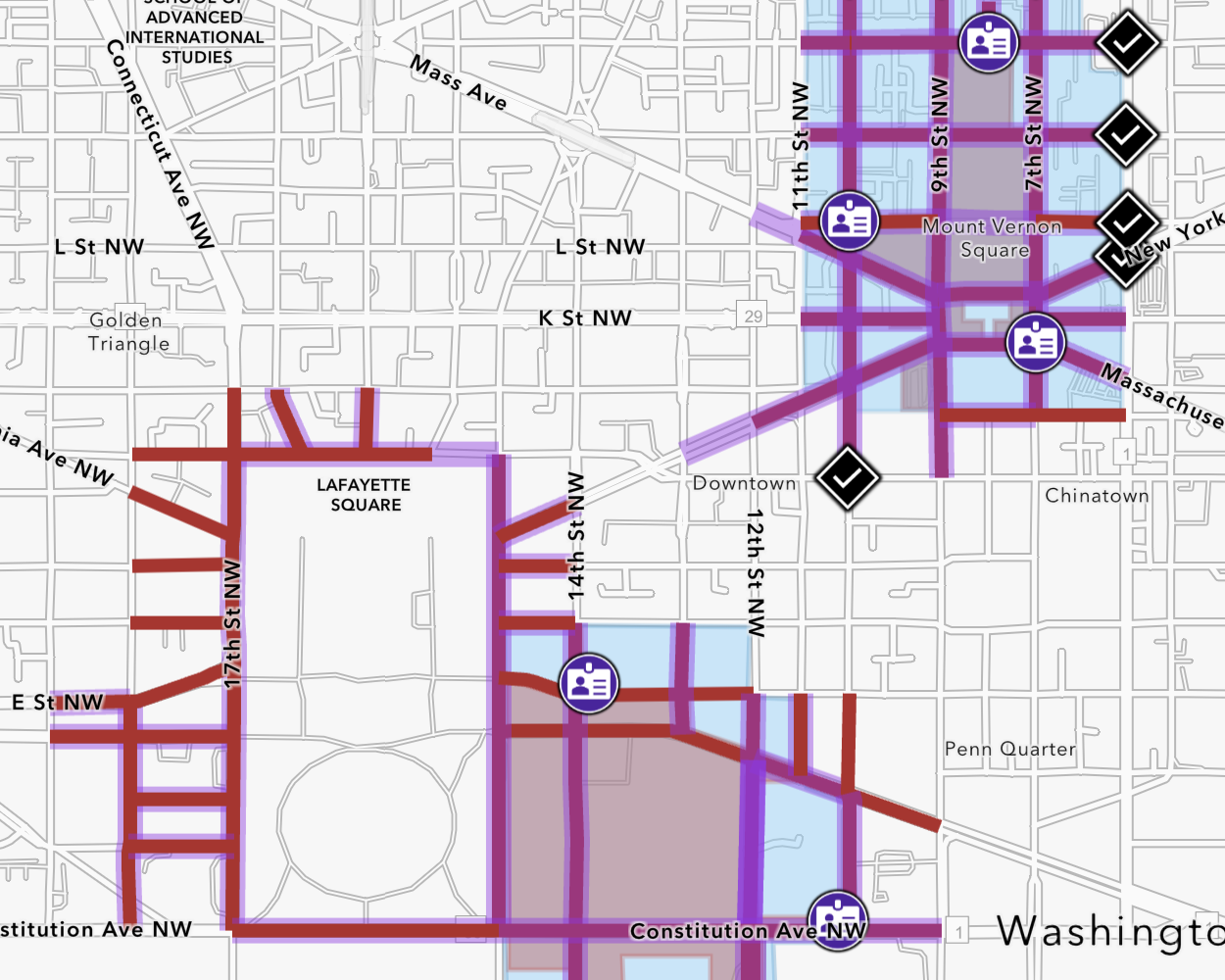

I don’t even agree with the premise that ATE is enforcement, because right now there’s no mechanism to actually use the data generated. Let’s say you rack up $10,000 in moving violations through ATE; the mechanisms that DC has to enforce some kind of consequence for that are very limited. DC boots about 50 cars per day, of those more than 600,000 boot-eligible cars.

Previously, there was a mechanism around license renewal, where you wouldn’t be able to renew your license if you had certain outstanding moving violations, but that’s also gone away.

I think the first the first thing would be to use the powers they already have in a more strategic way to boot cars in decreasing order of outstanding traffic fines. If they’re only booting 50 cars a day, they could try to make it the 50 very high-priority cars. There’s no data flow between the license plate readers that are fitted to police cars and any kind of intervention there. If a police car identifies a boot-eligible car on the road as it’s driving around, they could flag that to DPW. There are tools that DC already has, and I think they could reorganize their workflow and data flow in a more efficient way to intervene in public safety more effectively.

We also have a number of other initiatives that would take probably more legislative effort, efforts around the budget to fund Vision Zero and pursuing reciprocity with Virginia and Maryland.