On the morning of October 6, 2020, Evan Craig was sliced from sternum to pelvis. The foot-plus incision was splayed open with a metal retractor, and several pairs of hands began to rummage through about 20 feet of pulsing bowel, searching for cancer. The surgery was maximally invasive: Surgeons lifted organs out of Craig’s body, scrutinized them, and excised any suspect tissue. Ordinarily, after eight or nine hours, a nurse would snake plastic tubes into his abdomen, then pump the cavity full of heated chemotherapy solution to kill any free-floating cancer cells. Not this time. Nobody in the operating suite had seen a case like this.

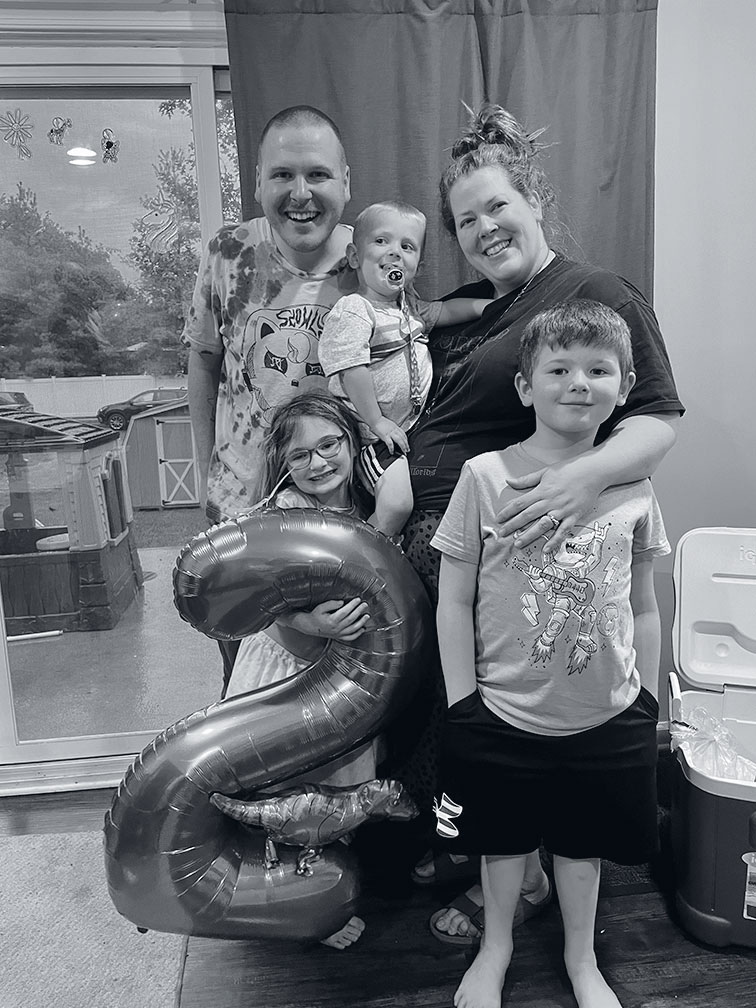

When Craig awoke, groggy and covered in staples, a surgeon delivered the news: They didn’t finish the operation. His cancer was far more advanced than scans had suggested. It had spread from his colon and abdominal wall to his pancreas—and, strangely, the superior mesenteric vein, which helps carry blood to the liver. There were no good options. Surgery and radiation would fatally mangle the delicate vein, and chemotherapy could ruin the quality of his dwindling life. Less than a year prior, Craig had been declared cancer-free after 12 rounds of chemo and a colon resection. Now he was unlikely to see his 31st birthday—or the coming birth of his third child.

For the next month, while his abdominal muscles healed, Craig couldn’t sit upright. He had ample time to gaze at the ceiling, reflect on three decades well lived, and make peace with his coming end. But there was no cinematic moment of clarity, no resolution to backpack the Nepalese Himalaya or taunt great whites from a shark cage. Instead, his days became formless. He bordered on catatonic. The antidepressants he’d been taking for three years didn’t make a difference.

A week before Thanksgiving, he received an email from his oncologists: The Aquilino Cancer Center was recruiting patients for a clinical trial. They advertised “significant improvement” in depression and anxiety after just one dose of psilocybin. They did not mention that psilocybin is the active compound in psychedelic mushrooms. These doctors were all business.

Cancer patients often compare the whole ordeal to an assembly line. They’re moved from specialist to specialist with ruthless efficiency, then they’re spit out into the world once they’ve passed a basic quality-control check.

The Aquilino Cancer Center, nestled inside the Adventist HealthCare campus in Shady Grove, is more like a lazy river. It specializes in peace of mind. The facility bundles oncology, chemotherapy, radiation, outpatient surgery, rehabilitation, and palliative care into one three-story package. On the ground level, patients and caregivers can find a social worker, a dietitian, and a navigator ready to wrangle transportation, financial support, and, on one occasion, a beach house in Ocean City. There are 29 different wellness programs open for enrollment, all offered free of charge. But when the emotional weight of illness grows too heavy to bear, patients are referred upstairs to the Bill Richards Center for Healing. There, the 25-person team at Sunstone Therapies helps them confront their fear of dying—and rediscover the joy of living—through psychedelic-assisted therapy.

In 2020, the Richards Center became the first non-university site in the United States to receive FDA clearance to conduct clinical trials with psilocybin. The initial study enrolled 30 cancer patients with major depressive disorder. (The waitlist was almost 300 names long.) Though the sample was relatively small—and did not include a placebo group—results suggest that a single six-hour trip, followed by two group-therapy sessions, could significantly outperform leading antidepressants. Patients felt less fear as well as a profound sense of meaning and acceptance. A recent follow-up study found sustained effects at 18 months for most participants.

Psychiatrists first began to study psychedelics in the 1940s. In the 1950s and ’60s, 40,000 Americans received LSD in clinics, typically for addiction, depression, and end-of-life anxiety. Dr. Betty Eisner, a noted midcentury psychologist, once likened psychedelic-assisted therapy to “four years of psychoanalysis in six hours.” Despite promising data, research came to a halt when the Nixon administration criminalized psychedelics under the Controlled Substances Act in 1970.

In 2000, after 30 years of prohibition, the federal government changed course, allowing scientists at Johns Hopkins to study the psychological effects of psilocybin in healthy volunteers. Two-thirds of participants who received the full dose rated the experience among the most spiritually significant of their lives. In the months after, subjects reported deep and enduring changes in their mood, attitude, and behavior. Today, psychedelics are being studied in more than 100 FDA-sanctioned trials, targeting two dozen mental- and behavioral-health conditions—from anxiety and addiction to anorexia and ADHD.

The boom reflects growing frustration with the sluggish pace of psychiatric-drug development. The last breakthrough came 41 years ago, when the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor was introduced to the European market. Though SSRIs—a category of drugs that includes Prozac—are still widely prescribed for depression and anxiety, they’ve been anything but revolutionary: Fewer than half of patients respond to them, the side effects can be worse than the illness, and it can take many months to discontinue treatment safely.

A noted psychologist once likened psychedelic-assisted therapy to “four years of psychoanalysis in six hours.”

Psychedelics have drawn an unlikely crowd of evangelists, and many of the cultural battle lines that defined the War on Drugs are being erased. You can find supporters in both former Texas governor Rick Perry and Representative Alexandria OcasioCortez; retired beatniks and the billionaire owner of the New York Mets; the former head of the National Institute of Mental Health and the former heavyweight boxing champion of the world. (It’s Mike Tyson. Obviously, it’s Mike Tyson.) It’s a bizarre coalition, united by optimism that the long-lost promise of psychedelic medicine may yet be fulfilled. And if that happens, the path probably will run through places like the Richards Center.

Entering the Richards Center feels a bit like boarding a spaceship designed by the Danish. The wall—singular, because it’s one infinite curve—is paneled with blond-oak slats. The leafy plants are larger than adult men. No lighting fixtures or bulbs are visible, yet a white glow spills out over the slate floor.

Sunstone Therapies is led by Manish Agrawal and Paul Thambi, seasoned oncologists in their mid-fifties. In early March, I join them for lunch in the center’s vestibule. Agrawal eats a tuna-salad sandwich. Thambi, who has the physique of a triathlete, orders turkey and cheese—on wheat, no chips. A golden retriever named Mattis lies at Thambi’s feet, eyeballing the sandwich.

Agrawal and Thambi met as first-year oncology fellows at the National Institutes of Health, and they had a great deal in common. Both had been raised by Indian immigrants struggling to find their footing. Both had worked as engineers after college and found the experience impersonal and unfulfilling. And both had quickly grown sick of the glacial pace of life at NIH. By 2004, Thambi had lured Agrawal to Maryland Oncology Hematology, the private practice now located on the second floor of the Aquilino Center.

Over two decades, they built impressive careers. They logged about 100,000 combined patient encounters, earned sterling reviews, and invested in technologies that radically improved prognoses. Still, neither doctor could shake the feeling that they were failing their patients. “You get very good at the technical aspects of cancer care,” Agrawal says. “Then you realize there’s still so much distress you haven’t addressed.”

In 2018, when Agrawal was the medical director of Aquilino, he stumbled on a paper from Johns Hopkins claiming that psilocybin could offer cancer patients six months of relief from existential angst. Agrawal is a skeptic by nature, a bioethicist and student of philosophy. The results seemed fanciful, so he drove to the campus to screen the team for quacks. He found none—only esteemed psychiatrists and tenured professors. Within a week, he and Thambi had signed up for a training program at the California Institute for Integral Studies, a crunchy one-building university near San Francisco’s Mission District. Over nine months, they attended lectures on psychedelic pharmacology, theories of consciousness, and therapy protocols. Both came away eager to launch a trial back home for their depressed patients—but first they had to convince their colleagues.

Fortunately, Agrawal is a bit of a square. “I have a lot of street cred,” he tells me. “I’m not a tie-dye kind of guy.” This is accurate. He is a gray-polo-and-jeans kind of guy—an ur-dad who describes his compost as “black gold” and cannot name many psychedelic-related books he has enjoyed. The duo pulled together a no-nonsense, data-heavy pitch and eventually won over their oncology partners, as well as Mary Greenberg, head of cancer-care services at Shady Grove Medical Center.

That was the easy part. Psilocybin is a Schedule I drug, meaning the Drug Enforcement Agency considers it to have “no accepted medical use” and “high potential for abuse.” Opening a clinic that solely administers such drugs is, by design, a near-impossible task. Agrawal and Thambi did it in nine months. “Those nine months were ten days of success and eight and a half months of toil,” Agrawal tells me, laughing harder than he has all afternoon. Thambi runs his hand through his hair, which is now entirely white.

To turn a 2,700-square-foot concrete shell into a functioning clinic, they enlisted Gensler, the architecture firm responsible for San Francisco International Airport, the 67-acre CityCenter in Las Vegas, and the 128-floor Shanghai Tower. The renovation cost $1.2 million, several times the normal per-square-foot cost due to all the requisite safety features.

Agrawal and Thambi had to locate a one-ton safe—during a global shipping crisis—haul it up several stories, and figure out how to bolt it to the floor. They also had to find research-grade psilocybin to store in that safe. Those chemicals can cost $7,000 per gram, more than one hundred times the price of gold. Often, savvy scientists will cajole biotech executives into sponsoring their trials, and that’s exactly what Agrawal did.

After swaying the FDA and DEA, the duo had to convince the Seventh-day Adventists—who sponsor Adventist HealthCare—that hallucinogenic drugs have legitimate medical utility. When discussing the Church, several interviewees mentioned “strong beliefs,” which feels euphemistic. Seventh-day Adventists don’t drink coffee, due to its corrosive effect on the mind; they underwrite church activities by selling Weet-Bix, a health cereal that looks and tastes like sawdust; they considered wedding rings an impermissible display of decadence until 1986.

Eventually, top brass came around, but only after a lengthy consultation process with religious scholars. Adventist HealthCare’s mission, after all, was to support “whole person” healing. If psilocybin could help mend the mind and spirit, they wouldn’t stand in anyone’s way. “They knew how important it would be for patients, who have such a fear of dying,” Greenberg says. “This was our last shot to help them feel peace.”

When the time came for Agrawal and Thambi to select a name for their company, Thambi’s nine-year-old daughter found something interesting on Wikipedia: The Vikings used calcite to enhance the sun’s light and guide them home even on the cloudiest days. They called it sunstone.

Nine months after Evan Craig’s failed surgery, an 82-year-old man urged him and three fellow travelers to “dive into the eye of the dragon.” The goateed octogenarian was Dr. Bill Richards, chief therapist at Sunstone Therapies and a dead ringer for the actor Brian Cox. Richards has, he says, the “dubious distinction” of being the last clinician to legally administer psilocybin in 1977 and also the first when research resumed in 2000. To date, he has led hundreds, perhaps thousands, of clinical sessions—Richards stopped counting several decades ago.

“When you confront what is frightening, it reveals its secret,” he told Craig and the other patients. “The monster becomes your alcoholic father in the middle of the night, or whatever it may be.”

Patients dispersed to their therapy dens, which are decidedly less elegant than the rest of the center. Not unlike a college dorm, there are fiddle-leaf-fig plants, a few tufted pillows, and gray vinyl couches that, if vomited on, can be wiped down expeditiously. Around 8:45 am, Thambi arrived carrying five pills in a glass dish. “It was kind of ritualistic,” Craig says. “But not in a weird way. Ceremonial.” Craig took one last look at a photo of his family, which by now included a seven-week-old boy, then donned an eye mask and headphones. His therapist would remain by his side the entire time—and later help him make sense of the experience in the group “integration” sessions. (In another room, a senior therapist sat before a wall of computer monitors, observing all four sessions simultaneously.)

The world felt brighter, sharper—as if he’d put on glasses for the first time.

Forty-five minutes passed. Just as Craig began to wonder if he’d been slipped a placebo, the darkness took three-dimensional shape. Time stretched and dilated and folded back in on itself. Over the next four hours, he danced with death on the astral plane. He was trash, washed up on a forgotten beach, where he would remain forevermore. He was a towering oak, lush with leaves—“like the Giving Tree,” he says. His children, Hunter, Scout, and Rudy, played at the base of his trunk. He embraced them with his branches, handing them a red apple. The air was warm and golden, but when he looked down, his roots were gnarled and decaying. He felt no despair: “I was still standing. I could provide for my kids.”

Then Craig was a white moth, in extremis, on the edge of a forested lake. A full moon tinted the surface silver, and fireflies illuminated the mossy banks. An eclipse of other moths surrounded his body, laying him to rest in the water. This was the End, but he wasn’t facing it alone. There was no cause for fear.

On the drive home, Craig says, the world felt brighter, sharper—as if he’d put on glasses for the first time. That night, over bento, he told stories with an enthusiasm his family hadn’t seen in years. He went eight months without another depressive episode.

Craig’s story, told in isolation, invites skepticism. But he wasn’t an outlier. Two months after dosing, 24 of the trial’s 30 participants saw their clinical depression scores drop by 50 percent or more—and 15 no longer qualified as depressed. “A couple of them, just recently, they’re off to Europe,” Richards says, waving his arms and rattling a beaded bracelet he wears to remind himself he can still do new things. “They don’t want to lie in bed and wait to die. They’ve got things to do.”

Psilocybin is a strange molecule. If you hook a rhesus monkey up to a machine that administers free heroin, the monkey will pull the lever continuously. Conduct the same experiment with psilocybin and most primates call it quits after the first go-round. It’s non-habit-forming. There’s also no feasible way to overdose, unlike with alcohol, caffeine, or Tylenol. By one estimate, a 130-pound adult must consume 37 pounds of fresh psilocybe mushrooms in one sitting to risk toxicity.

When the body metabolizes psilocybin, “people step outside the loop of fear, gain a new perspective.”

There’s no ironclad explanation for how mushrooms work their emotional magic, but leading theories revolve around the default mode network, a system of brain regions that light up when the mind is otherwise idle. When the network activates, we daydream; we try to interpret our past, make sense of our present, and game out our future. In Freudian terms, this is where the ego lives. When the body metabolizes psilocybin, the default mode network goes quiet—the “ego” temporarily dies. At the same time, overall brain connectivity increases. That state of mental clarity may create an opportunity to break free from cycles of rumination.

“In that room, people step outside the loop of fear, gain a new perspective on their lives, and realize that their cancer is no longer all-consuming,” Agrawal says. “They start to see that they have a choice in how they face this.”

Extreme mental pliability, or neuroplasticity, isn’t inherently beneficial. In that impressionable state, a traumatic experience could leave lasting scars. This is why patients with schizophrenia in the family are routinely screened out of trials. It’s also why practitioners are so focused on curating settings that minimize panic and paranoia. The therapy, Agrawal insists, is the entire experience—not just the drug itself. “If MDMA alone could cure PTSD, then everyone who went to a rave wouldn’t have trauma anymore,” he says.

The experience at the Richards Center—the design of the room, the music, the timeline—has been carefully refined over six decades by the center’s namesake. Bill Richards first took part in a psychedelic experiment in 1963 while studying at the University of Göttingen in Germany. Then 23 years old, he’d heard rumors about a strange psychiatric clinic on campus, around the corner from his dormitory. It was studying a drug said to induce “experimental psychosis” and dredge up lost memories from childhood.

A dream obsessive who sometimes skipped breakfast to journal about his nightmares, Richards was intrigued. “I thought maybe I could get some new insight into my Oedipal complex,” he says, stone-faced. A research assistant led Richards to a cramped basement room overlooking a dumpster, injected a mystery drug into his arm, and left him alone in the dim light for three or four hours. Throughout his trip, garbage collectors clanged metal cans. In the middle of the session, a man in a white coat walked in to tap Richards’s patella with a hammer. “I remember sitting there with my arms outstretched, feeling compassion for the infancy of science,” he recalls. “They had no idea what was going on.”

Despite the spartan conditions, Richards had stolen a glance at something transcendental. That evening, he trudged up three flights of stairs to his dorm room, prostrated himself across the floor, and scribbled 12 words in his journal: “Reality is! It is perhaps not important what one thinks about it!” He became known around the clinic as the “interesting American who had the mystical experience,” and he was hired to guide other English-speaking research subjects, including medical tourists from the United States.

Over the next decade and a half, Richards became a giant in the field, administering LSD to hundreds of cancer patients, “neurotics,” and alcoholics at universities and hospitals. Even as federal grant funding dried up, Richards and his team managed to work through 1977, like World War II holdouts on a remote island in the South Pacific. “I wondered if it would ever come alive again in my lifetime,” he says, wheezing rather wistfully. “Look where we are now. This is beyond my wildest dreams.”

Agrawal, who admits he can be “sort of dreamy,” asks me if he can pitch something that’s been on his mind for months. “Paul and I have been Washingtonian top oncologists,” he tells me. “This is a story about two guys who left oncology to create a new specialty: psychedelic medicine. And in three to five years, you’ll vote for the top psychedelic doctors.”

Thambi, the disciplinarian, lets out a nervous laugh. “He’s relentless, this guy.”

It’s a big promise. Treating patients safely, at scale, and with buy-in from insurers will be challenging. But that’s where Sunstone hopes to shine. “Without the infrastructure, none of this happens,” says Kimberly Roddy, the company’s cofounder and chief operations officer.

Roddy knows infrastructure. When she took the operational helm at Maryland Oncology Hematology in 2011, the practice employed fewer than ten doctors. By the time she left in 2021, it had brought in $1 billion—and grown to 11 offices, nearly 50 physicians, and 350 employees. While there’s scant precedent for bringing a pharmaceutical “experience” to market, radiation and infusion chemotherapy seem to be the closest analogs. If anyone can figure this out, it’s probably oncologists.

By the end of 2023, Sunstone will have active studies for five different psychedelics—psilocybin, LSD, MDMA, ketamine, and 5-MeO-DMT. It plans to gradually expand eligibility, opening several anxiety and PTSD studies to people without cancer.

Some trials will focus on underexplored scientific questions: Can a second “booster” dose of psilocybin help cancer patients who didn’t respond the first time? Can MDMA-assisted therapy administered jointly to patients and a caregiving family member help both cope with their distress while strengthening relationships commonly strained by the stress of serious illness? Others will assess new ways to reduce the cost of treatment—making it more accessible and more likely that insurers will help foot the bill. The company also sees potential in shorter-acting drugs. One of them, 5-MeO-DMT, a powerful psychedelic derived from toad venom, induces a 20-minute trip that only feels like eight hours.

The coming surge in foot traffic makes staff a little antsy, but volume is the only way to prove the concept. “You need enough people running through the center to actually understand where your pressure points are and how you solve for them,” Roddy says.

If all goes according to plan, there will be six to ten Sunstone “centers of excellence” by 2030. These regional research hubs, each with a unique specialty, will feed new findings to a larger network of clinics. One hub might focus on how to improve mental-health care for veterans; another might investigate ways to incorporate artificial intelligence and virtual reality into psychedelic-assisted therapy. Sunstone is already thinking about how to staff those centers—the psychedelic workforce will need to grow by several thousand clinicians to meet projected demand. Recently, the company welcomed the first 20-person cohort into its therapist training program.

The FDA seems likely to approve MDMA for posttraumatic stress sometime in 2024. Psilocybin could get the green light by 2025. It could also take years or decades—or maybe it never happens. Sunstone moves fast, but the medical establishment does not. Questions linger about trial methodology and real-world efficacy. Drugs are almost always less effective outside of tightly controlled trials, and the hype around psychedelics could create a placebo effect.

Agrawal and Thambi left lucrative careers, one decade from retirement age, to prepare for a future that’s far from guaranteed. When I bring this up, they’re unbothered. “Leaving was hard, but I have not gone downstairs once,” Agrawal says. “I love that chapter in my life. I learned so much about myself, my patients, my colleagues, but that’s a coat that doesn’t fit anymore.”

Thambi nods. “The people that get the most out of those medicines are those who learn how to accept and how to let go,” he says. “That’s something I’m also learning.”

They have plenty of teachers. Evan Craig, despite his surgeon’s doomsaying, continued chemotherapy for his cancer. After two cycles, he’s once again in remission. “If I didn’t have my kids, I probably wouldn’t have fought nearly as hard as I did,” he tells me. “I just can’t imagine not being their dad, not being there for them.”

With his newfound energy—and patience, courtesy of psilocybin—Craig is making up for five years of lost time. He can finally walk his daughter down to the duck pond, screech like a velociraptor while chasing his youngest around the yard, and feign enthusiasm when the kids ask to watch Frozen again. He could live six decades or six months. No one can say. But he doesn’t have time for hypotheticals. He is here now, and he’s got things to do.

This article appears in the July 2023 issue of Washingtonian.