Last August, the Washington Post revealed a macabre and largely obscure part of the Smithsonian’s collections: It holds more than 250 brains that an anthropologist obsessed with race collected in the first half of the 20th century. Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III apologized for the collection and told the Post the brains “need to be returned if possible.”

That work is proceeding slowly, the Post reported last week. Only five brains have been repatriated so far. A significant percentage of the brains comes from DC, and in addition, the National Museum of Natural History holds more than 30,000 bones and body parts from human beings, many of which appear to have been gathered without the consent of family members. Some in the Smithsonian resisted returning the body parts, the Post reported last week, and it also published, as a public service, a database that will serve as a starting point for people researching the Smithsonian’s body-part holdings.

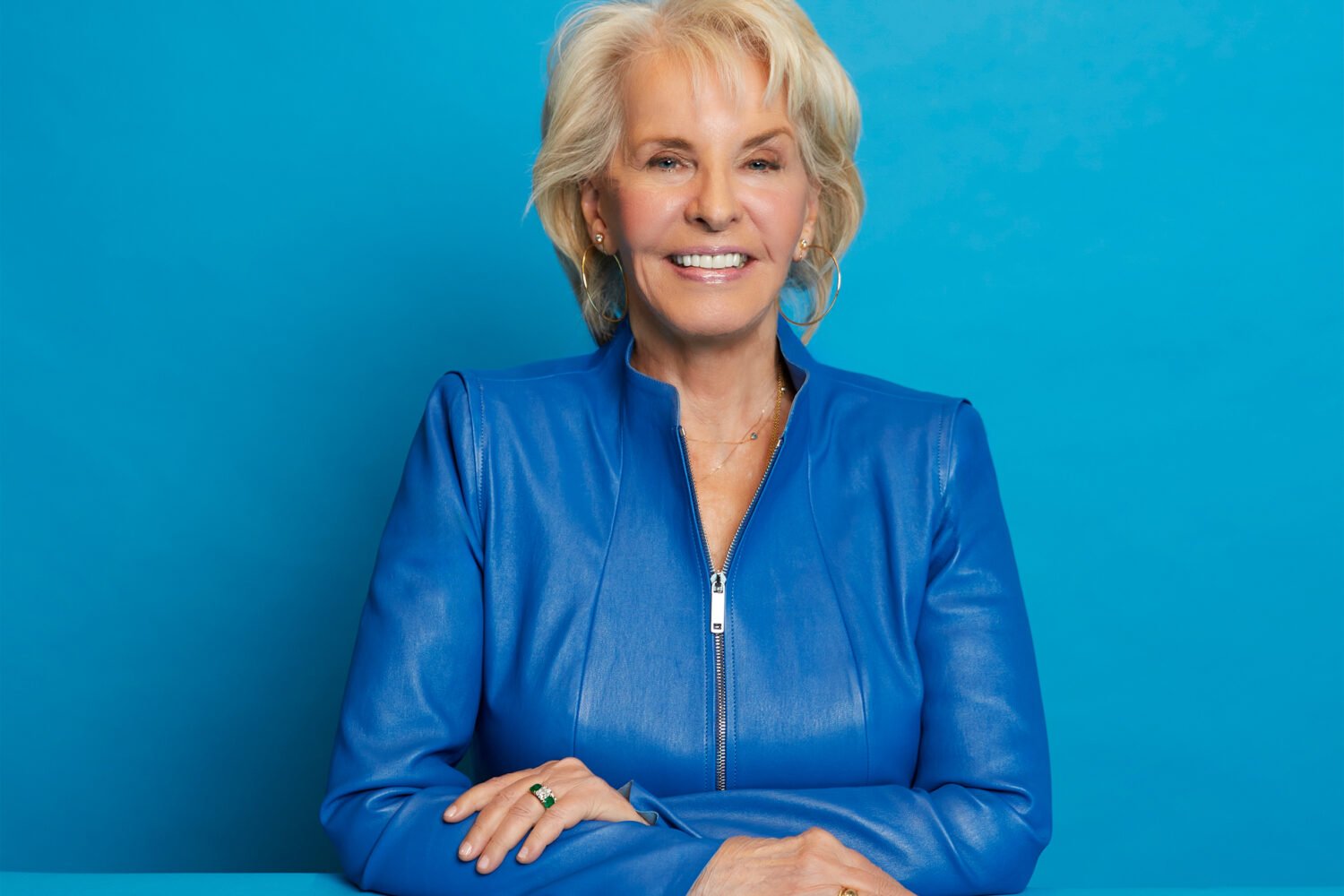

Nicole Dungca is one of the lead reporters on the sprawling story, which involved more than 90 people and has grown to comprise videos, podcast episodes, and a graphic novel that you can order in physical form. “I think many people don’t know this chapter of our country’s history,” she says. “Native American communities have known for many years, because they had been disproportionately affected.”

Dungca is a reporter on the Post‘s investigative unit and a veteran of the Boston Globe‘s storied Spotlight team. She began reporting on the Smithsonian’s body-parts collection in late 2022, after her coworker Claire Healy started to look into the work of the Filipino American artist Janna Añonuevo Langholz, who had discovered that brains from four Filipino people who’d been put on display at the 1904 World’s Fair had ended up in the Smithsonian’s collection. “It was really just kind of a dream for a Filipino American reporter to be able to take on this kind of project,” she says.

The graphic novel, illustrated by the Filipino artist Ren Galeno, tells the story of Maura, an 18-year-old Filipino woman who died of pneumonia before the fair opened. Smithsonian anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka, who believed white people were superior to others, arranged for what appears to have been Maura’s brain and eventually three others to be sent to Washington for study.

The work for the story was massive, Dungca says. The Smithsonian provided a spreadsheet with the locations from which body parts had been donated, and another that included information on the donors—but not the people whose remains ended up in the collection. She and others dug through death records, matching as many as they could to actual people. The Smithsonian’s archivists, she says, were very helpful.

One result has been rediscovering the stories of people whose lives were devalued by Hrdlicka’s predation. In addition to Maura, the Post team identified Mary Sara, a Sami woman whose brain the Smithsonian returned after its initial articles in August. Here in Washington, they zoomed in on the story of Moses Boone, a toddler who died at Children’s Hospital in DC in 1904. Hrdlicka performed his autopsy and kept his brain. They found Michelle Farris, a distant relative who lives in Glen Burnie, and accompanied her to Mount Zion Cemetery in Georgetown, where Moses was buried without a gravestone. “I just want to give him his peace,” she said.

By combining the Smithsonian records with their own research—which involved a lot of perusal of microfilm—the team was able to “really build out a picture of this brain collection that had never before been seen,” Dungca says. The Smithsonian is not subject to federal Freedom of Information Act laws, but it has pledged to follow the law’s spirit. Still, Dungca says, the Smithsonian wouldn’t let Post reporters see where remains are stored at its Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland, citing the need to respect the deceased and the wishes of tribes, and that it initially limited their access to Hrdlicka’s papers, citing privacy concerns. “Which was surprising to us,” Dungca says.

A Smithsonian task force will issue recommendations about how to repatriate body parts in its collection within the next few weeks, says Linda St. Thomas, the Smithsonian’s chief spokesperson. A federal law from 1989 requires only that the Smithsonian notify Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Alaska Native communities that it holds remains, and repatriation of those remains has gone slowly, St. Thomas says. In an op-ed published in the December issue of Smithsonian magazine, Bunch wrote that the Smithsonian owns “a collection that should have never been amassed, and we’re committed to dismantling as much of it as possible in a way that recognizes and honors the people affected.”

But despite that commitment, Dungca says, the Post‘s reporting shows that it may be a very long time before the Smithsonian reaches that goal: “There are thousands of human remains at the Smithsonian,” she says, “that are still in limbo.”