When archaeologist Travis Parno got a job at Historic St. Mary’s City in 2016, he was intrigued by a major unsolved mystery: Somewhere nearby, buried underground, was an important 17th-century fortification that historians had been trying to locate for almost a century. “It was like, wait, there’s a fort here that hasn’t been found yet?” Parno recalls. “That’s pretty neat.”

Built in 1634, the wooden rectangle was the first structure that English settlers erected in Maryland. It was the seed of what would become St. Mary’s City, which was Maryland’s capital until 1695. Now preserved as the living museum Historic St. Mary’s City, it features more than 300 archaeological sites, along with carefully researched recreations of some 17th-century buildings. But despite decades of effort to locate the original fort, nobody knew where it was.

With his tousled black hair and electric-blue eyeglasses, Parno could be a creative director at a New York ad agency. His rolled-up sleeves reveal elaborate archaeological tattoos: prehistoric paintings from Chauvet Cave, the leathery face of Tollund Man. For Parno, the ongoing puzzle of the fort’s whereabouts was too tempting to resist. About a year after he came aboard, he decided he wanted to find it.

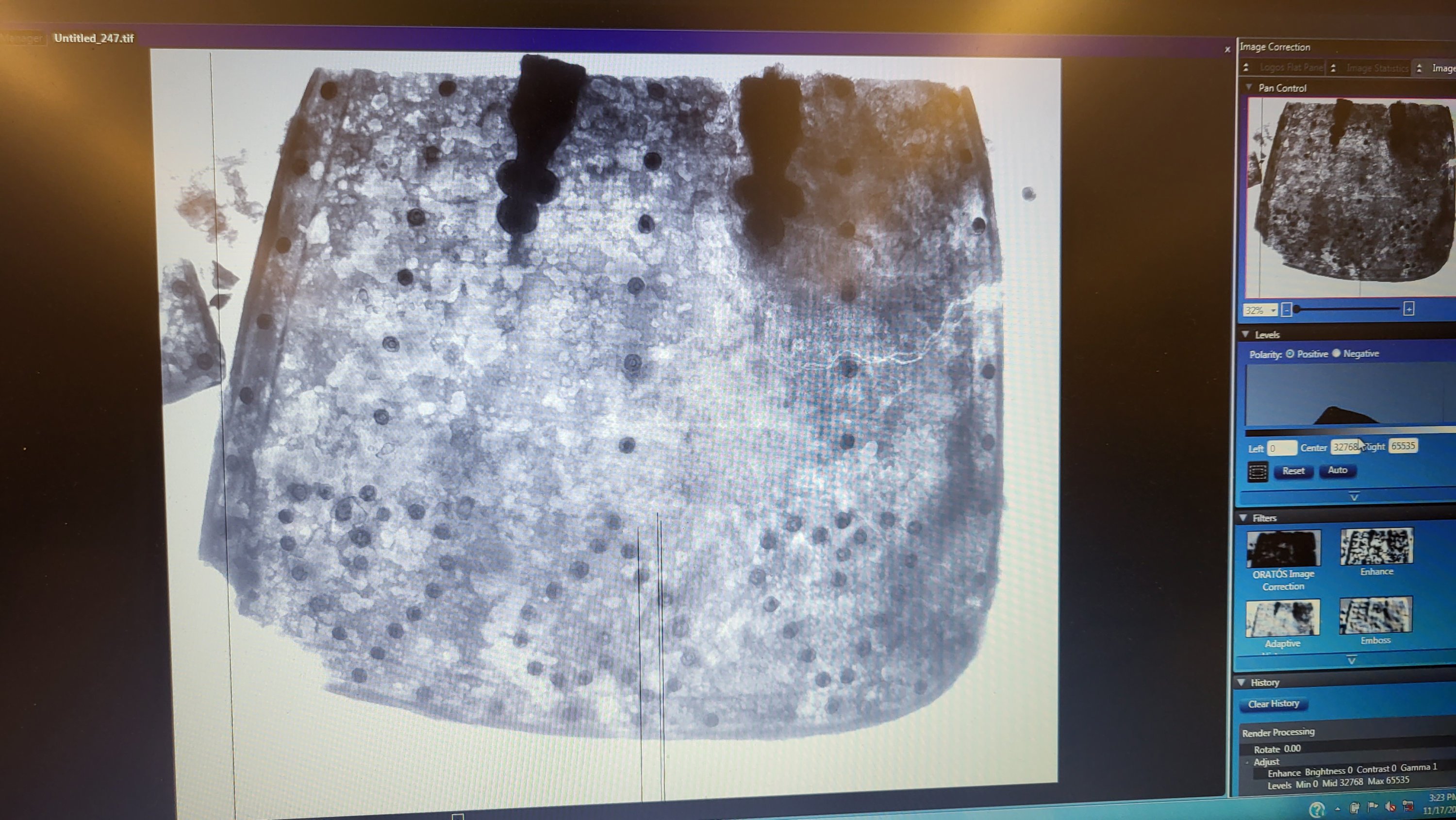

So Parno—who today is director of research and collections at Historic St. Mary’s City—got a grant from the Maryland Historical Trust and brought in geophysicist Tim Horsley, an expert in modern detection methods such as ground-penetrating radar. Horsley’s initial efforts didn’t yield much. But in November 2018, he began to push a lawnmower-like radar device in straight lines over areas they’d identified as potential locations. It would be slow work, and Parno left for a scheduled vacation, assuming he wouldn’t miss much: “I was like, yeah, he’s not going to find it in the first three days.”

Parno, a man of nerdy enthusiasms, was heading not to the beach or a cabin but to a board-game convention. He was in the middle of a game about the pre-Aztec civilization Teotihuacán when he got a text from Horsley. “Hey Travis. I hope you’re enjoying Philly! So . . . we got it!”

Horsley went on to say he’d found what he was confident was solid evidence of the fort. “This is incredible,” Parno responded. After some discussion of the specifics, Horsley told him to get back to his vacation. “Screw the vacation!” Parno replied. “Thanks for letting me know!!”

Parno’s head was spinning. “It was immediately just holy shit. I called my boss, I called my wife. Because this was huge for me, but also for Historic St. Mary’s City, for Maryland.” Then he headed back to his game and tried to explain to the guys he was playing with what was going on. “They are like, ‘Can I take my turn?’ ” he recalls. “I’m like, ‘No, no, guys, this is a really big frigging deal!’ And I didn’t say frigging.”

It took four months for the 150 or so settlers to cross the Atlantic in a pair of ships called the Ark and the Dove. In March 1634, they sailed up the Potomac River to what’s now known as St. Clement’s Island and then ended up in the nearby location that became St. Mary’s City. Once there, they engaged with the Yaocomaco, who inhabited the area but had decided to leave. The settlers negotiated to acquire the land. The deal was finalized on March 25—a date now celebrated every year as Maryland Day. It was just the fourth permanent British colony in America, established 14 years after Plymouth.

The expedition’s leader, Leonard Calvert, set everyone to work building a fort, and soon the settlers moved in. It was a rudimentary palisaded structure roughly the size of a football field—walls about ten to 14 feet high, bastions in at least two corners—but it was enough to get the colonists through those earliest years. As the community grew and established itself, they began to move out into the surrounding area, and less than a decade after it was built, the fort was gone. Nobody is certain why, but in 1642, mentions of the fort disappear from historical records. “I think it was probably just allowed to fall over, to decompose,” says Parno.

If that’s what happened, no wonder it was hard to find. There had never been a record of the fort’s exact location—no map from the time, no precise coordinates. Archaeological sleuths had one major clue: a letter written by Calvert in 1634 describing the spot as being on the east side of the harbor, within a half mile of the river. That wasn’t much to go on.

In the 1930s, an architect named Henry Chandlee Forman kicked off the modern search for the fort. While exploring the area, he uncovered some significant brick buildings from later in the 17th century, and his 1938 book, Jamestown and St. Mary’s: Buried Cities of Romance, became a foundational text on Maryland’s early days. But his efforts to unearth the fort were fruitless. By 1966, when Historic St. Mary’s City was founded, the focus turned to launching the museum; the lost fort was less of a priority.

Then, in the 1980s, archaeologists from Historic St. Mary’s City were called in to examine a field that nobody had paid much attention to. The spot was being eyed for a hotel, and just to be safe, the team did a “controlled surface collection survey,” which essentially meant plowing the field and looking to see what got turned up. Intriguingly, there were a number of artifacts from the earlier part of the 17th century, including two cannonballs—a significant clue. In 1991, Parno’s predecessor, Tim Riordan, published an article speculating that the field might have been the site of the fort. But nobody was able to confirm it.

The hotel never got built, fortunately. Three decades later, when Tim Horsely was mapping out his survey plans, one of his primary targets was Riordan’s field. Finally, the radar was able to spot what Riordan suspected: There, unmistakable on Horsley’s computer screen, were traces of the fort’s rectangular palisade trench. Parno and his team then spent 2019 excavating part of the area, and what they found confirmed that this was the fort. They decided to make the big announcement in March 2020.

Visitors are warned to step carefully; Should an errant foot damage the site’s grid markings, the klutz has to buy the crew a case of beer.

Covid’s arrival scuttled those plans, but after a one-year delay, Historic St. Mary’s City and then-governor Larry Hogan held an online event to share the discovery. It made international news. “Archaeologists and historians had been waiting for this moment for many, many years,” says James Horn, president and chief officer of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, who studies the earliest British colonies in America. “It’s just extraordinarily difficult to find a footprint that is so ephemeral. Finding the site of the fort gives us a good idea about their daily lives in a way that the purely historical sources cannot. By having a precise location of that first settlement, we can begin the story.”

Parno himself wasn’t able to be in St. Mary’s when the news broke. His wife had gone into labor almost eight weeks ahead of her due date, and he found himself fielding media calls from a bathroom in the hospital. “It was like, ‘All right, your next interview is with the BBC,’ and I was like, ‘Sure, whatever,’ ” he recalls. “It was a very weird time of my life.” Those few days were tense, but his wife and son ended up being fine. The baby’s birthday was March 25: Maryland Day.

If you were a fan of Indiana Jones movies as a kid, you might be a bit disappointed when you arrive at the St. Mary’s Fort excavation site. There’s no massive scaffolding apparatus, no legions of workers ferrying priceless artifacts. The location is marked by a pair of white canopies, which shade a patch of exposed dirt gridded out with string. Visitors are warned to step carefully; should an errant foot damage the grid markings, a running joke at the site goes, the klutz has to buy the crew a case of beer.

Despite the modest setup, the archaeological effort has already yielded big results. During the field season—March to December—workers spend their days repeating a laborious process. First they dig up a carefully marked patch of dirt and carry it by bucket over to a horizontal screen. Then they sift through the dirt with intense care, pulling out anything that appears noteworthy. That can be pottery shards or a coin made around 1633, a cannonball or a thousand-year-old Native American arrowhead. Sometimes it’s hard to know what it is. When I visited recently, Jessica Edwards, the site director, showed me an oddly shaped stub. “I think this is a wig curler?” she said. “That might be what this is.”

One discovery was a plate of early-17th-century armor. Other finds have been grimmer, such as a boy whose legs were mangled from the accident that probably killed him.

Many of these artifacts would be invisible to an untrained observer. Parno is especially excited about some thin strands of metallic thread, which don’t look like much of anything and would have been easy for the dig team to miss. “This is what archaeologists get jazzed about versus everybody else,” he said, holding up a clear vial containing the thin strings. “This was the height of fashion in the 17th century, to have clothing embroidered with, probably, silver thread. You are the rich of the rich. You’re looking at someone like Governor Calvert or one of his high-level associates. That’s pretty cool.”

One of the biggest discoveries was pulled out of the ground late last year: a plate of early-17th-century armor that’s decorated with heart-shaped clusters of rivets. Other finds have been more grim, such as a teenage boy whose remains were just outside the fort, his legs badly mangled from the accident that presumably killed him. “It was a challenging place to live,” Parno says. “A lot of people died.”

After artifacts are unearthed, they go to Historic St. Mary’s City’s nearby Department of Research and Collections building, where Parno spends much of his time. In addition to offices, it houses expansive archaeological laboratories and a third-floor storage facility that safeguards most of the 6.5 million artifacts collected from various locations around St. Mary’s over the last 50 years.

A lot of that stuff is primarily of interest to archaeologists, but some of the most exciting pieces will soon be on display in the museum’s new visitor center, which opens next year. And Historic St. Mary’s City does encourage people to visit the fort site. There are daily tours, or you can just walk over to the field and chat with the archaeologists who are at work. They might even show you something they just found—meaning you would be only the second person to lay eyes on it since the 17th century.

And soon the site will get a lot more visitor-friendly. Parno is eager to help people get a better sense of what they’re looking at, and plans are underway to build a partial reconstruction of one corner, along with ramps and other visitor infrastructure. The goal is to unveil it all in early 2025.

Those efforts have meant moving away from some of the most exciting unexcavated parts of the fort, especially the cellar of a storehouse that seems to have been used as a trash dump. That area has already proven to be packed with fascinating objects, including that piece of armor. But any further exploration has been put on hold until next year due to limited resources.

Surely that must be frustrating for somebody whose life is so devoted to discovery? “The impatience, the push to do more, is always there,” Parno told me. After spending just a few hours hanging out at the site, I was already hooked. “I just want to know,” I told him. He gave me a little welcome-to-the-club smile, then replied: “So do we.”

This article appears in the July 2024 issue of Washingtonian.