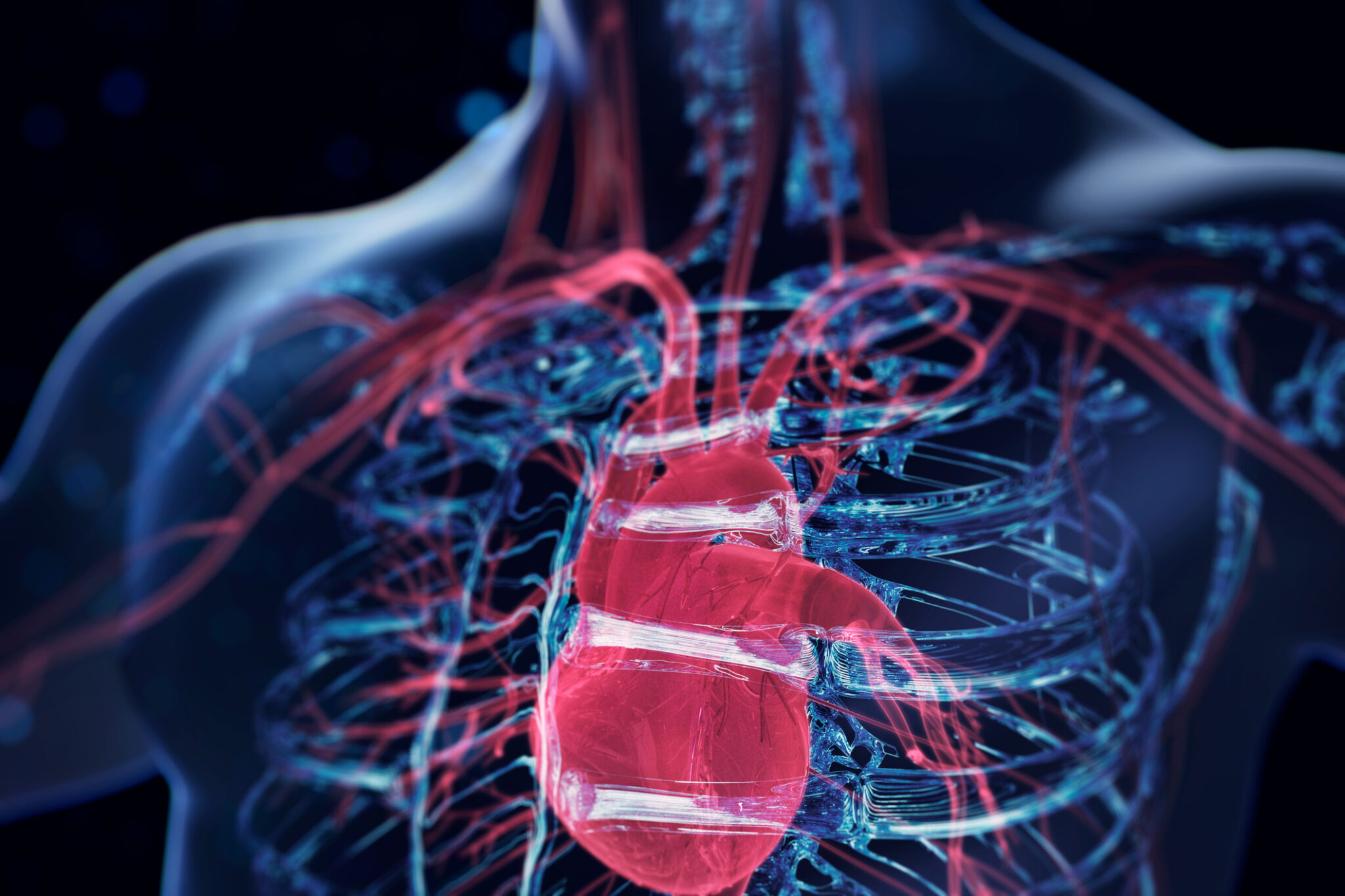

Watch your heart this week, because studies of the 2020 election show that contentious elections can be very hard on the old ticker, and the risk of a heart attack can increase as we wait for returns.

The Harvard Heart Letter says that according to a 2022 survey by JAMA Network Open, heart attack rates skyrocketed 42 percent in the days following the 2020 presidential election. Diagnoses of acute cardiovascular conditions were 17 percent higher after that election, according to the National Library of Medicine. Plus, if you are already genetically predisposed to stress (for instance, if you already have anxiety and depression), the risk is more than tripled during stressful events, according to the American College of Cardiology.

This probably isn’t a complete surprise. But what does this mean in the context of the high-stakes 2024 presidential election? We chatted with a DC-area cardiologist to learn more about how to take care of yourself this week.

How do you know if you have a heart attack? Medically, what’s happening in your mind and body, and what are the signs?

Dr. Stuart Sheifer (Virginia Heart): The classic symptoms of a heart attack would be a pain or pressure in the center of the chest, classically radiating up into the neck, the jaw, the arm, particularly the left arm, often accompanied by shortness of breath, nausea or sweating. Those would be what we call red flags.

What’s also important to recognize, though, is that the symptoms can be variable. We need to be particularly careful that there’s a broader spectrum of symptoms in women: just shortness of breath, or perhaps abdominal discomfort, or perhaps back pain.

How do stressors get heightened during an election?

It is definitely the case that stress and acute stress, or acute or chronic stress, can trigger cardiac processes. We do know that heart attack events, which are acute coronary processes, can have certain triggering events that trip off what might have otherwise been stable coronary arteries to become unstable. Acute stress can have any number of physiological impacts. Acute stress can have any number of physiological impacts, including heightened adrenaline levels, adrenal hormone levels, higher heart rate, higher blood pressures, more cardiac stress and more cardiac workloads. We tend to see acute chronic stress as something that tightens one’s risk of evolving to a true heart attack above what their baseline risk would be.

What are other heart problems that people should be aware of at this time?

Coronary processes like heart attacks most typically have to do with the state of blood flow through our coronary arteries, the plumbing system of the heart. That’s what a heart attack is all about. And there also can be this phenomenon of extreme stress, and actually toxic levels of adrenaline, leading to this other phenomenon called Broken Heart Syndrome, or stress disease, carbon iopathy, which is a little bit different, and that describes the person that has an acute, extremely stressful circumstance.

We see this in people who may have something shocking happen—the loss of a loved one, extreme grief or extreme stress of other types—and all of a sudden they have an acute stress mediated impact on their heart. People who have this, we can actually see them have chest pain. We can see them have EKG changes. When we do echocardiogram studies on them or ultrasounds on the heart, we see there’s a certain abnormality of how the heart muscle moves. This is all we believe, based on adrenaline toxicity: that there’s so much adrenaline surging through the system that it’s actually toxic to the heart muscle. It’s called takotsubo cardiomyopathy. It’s a Japanese term for an octopus bottle. When they capture octopi, they place them in these bottles that have this certain shape. Someone actually figured that the way that the heart will submit, this looks like that.

They can be very similar. But the difference is, one is a true sort of acute change in the coronary status and a progression from what was stable plaque in the arteries to unstable plaque. That’s what a heart attack is, or a myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome. The other is something where it’s really a toxicity of adrenaline to the heart muscle, creating this bizarre phenomena. It is possible that we could see, in emergency rooms, elements of both phenomena over the coming days.

Is there something about being in this area that contributes to higher risks of heart attacks?

We’re at a higher population risk than perhaps other geographies, from the standpoint that we have so many people whose work is aligned with our political process, or who work in government, and might perceive that they would be more profoundly impacted by the outcomes.

What are the best strategies to mitigate risks?

We really, really want to emphasize that if people are starting to feel anything along the spectrum of symptoms described, they promptly seek care in an emergency room and not delay assessment of what could be an important and time-dependent cardiac process.

But the other would be on the preventive side. We would wish for our patients and our community neighbors to be practicing mindfulness, particularly this year, and particularly for those who already have heart disease or those who are at risk, but truly for all of us. It would be a value for us to intentionally practice stress reduction techniques, breathing exercises, tai chi, yoga. All of these elements of mind-body care have been shown to be beneficial from a cardiovascular perspective, in terms of mitigating stress, but also lowering blood pressure and lowering heart rate. And while the data will never probably be absolutely clear, it intuitively makes sense that practicing such things would lower one’s risk of having acute heart strain from stress and anxiety.

How have you seen this phenomenon change over the years?

I think those of us who’ve practiced for a long time have had more episodes of stress and anxiety with mediated cardiac symptomatology and cardiac events in the face of these inflection points of geopolitical stress. So those of us who cared for patients and provided clinical care around 9/11, we saw more of this in the aftermath. We saw more of this in the 2016 election, in the 2020 election. We saw more of this at the advent of Covid, not just based on Covid impacts on the heart but the stress of the pandemic and triggering stress mediated cardiac symptomatology and events.

How does it feel to witness patients during these highly stressful times? Especially in life-threatening situations?

Part of our mission as healthcare providers is to ride through the various phases of population health phenomena that come through our society. It’s our role and responsibilities to continue to provide care. But I would say that all of us as a healthcare community probably just have a heightened sensitivity to these phenomena, as we care for patients and as we see patients come in reporting symptoms to have just a little bit more sensitivity and awareness that the triggering event could possibly be stress mediated. Not only do we need to treat the acute processes in front of us, but also understand the underpinning a bit to help optimally care for them and prevent and mitigate against future challenges.

If you’re experiencing a life-threatening medical emergency, please call 911! If you’re looking for a cardiologist, check out the Top Doctors list from our November issue.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited.