On a rainy Tuesday morning, I stood under Abraham Lincoln for the first time. “Those reinforced concrete beams are actually where Abe is sitting right now,” said Sam Meyerhoff, a senior project manager in the DC office of the construction company Consigli, as she pointed some 40 feet in the air. We were standing in the undercroft, the cavernous, column-lined space under the Lincoln Memorial, as Meyerhoff was helping lead a tour of the ongoing construction of the site.

When it was built more than a century ago, workers elevated the memorial above the National Mall by sinking 122 concrete pillars into the bedrock, leaving some 50,000 square feet of empty space underneath the marble likeness of our country’s 16th president. Call it the nation’s basement. It was off limits to visitors, something of an urban legend—the only hint of its existence a small bookstore and exhibition area tucked underneath the memorial.

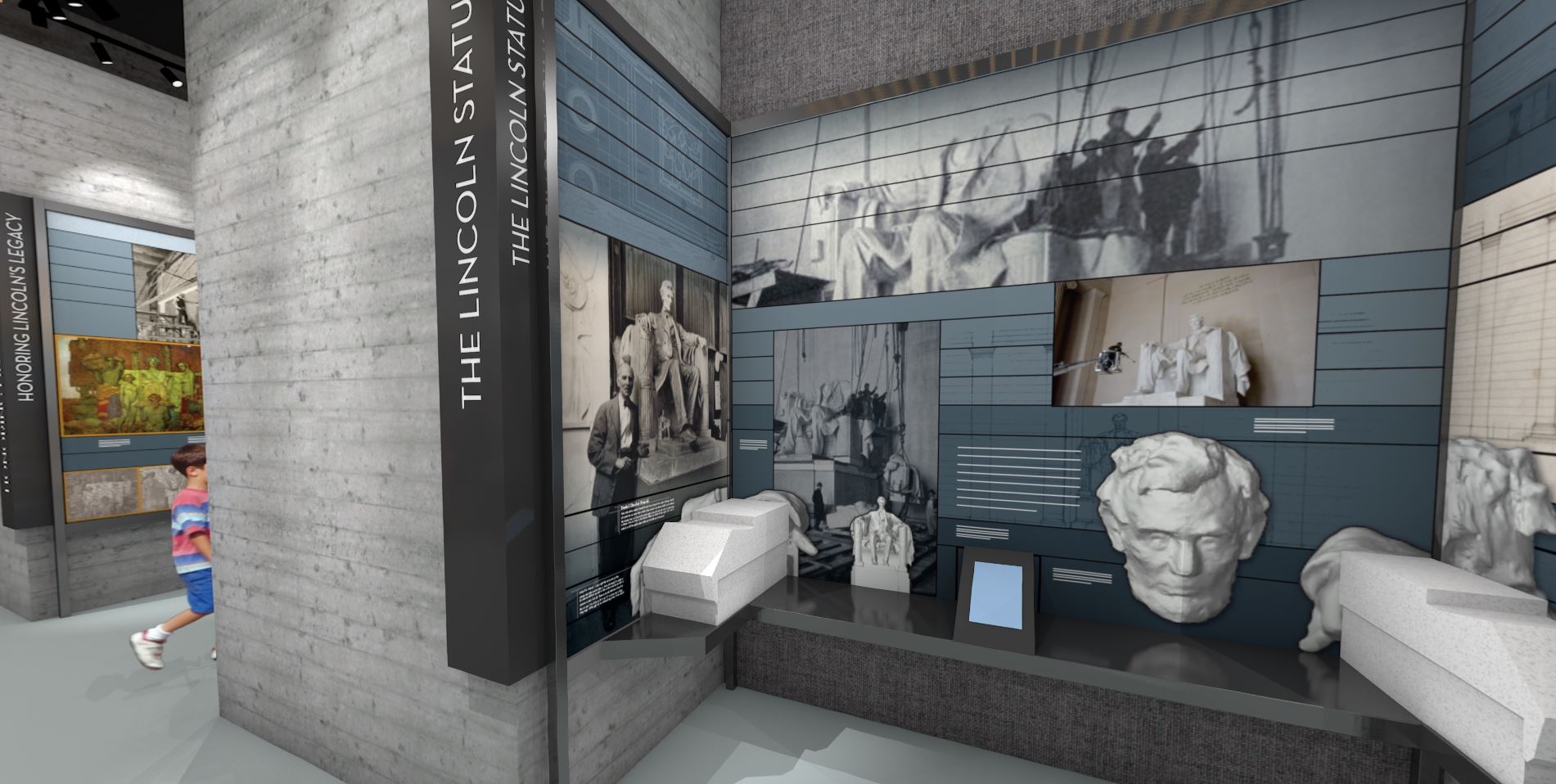

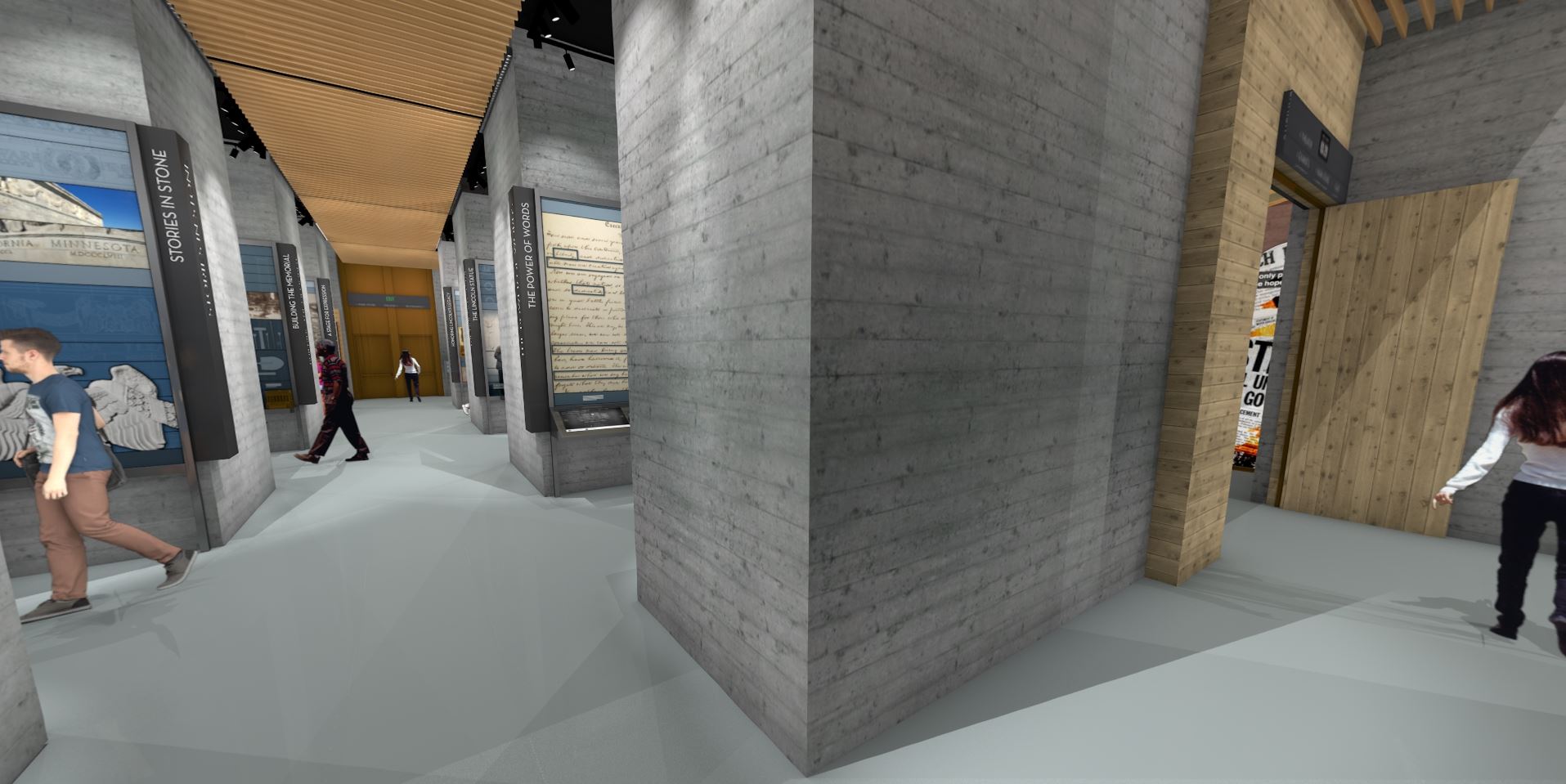

But now, as part of a $68 million-plus project, the undercroft will be transformed into a 15,000-square-foot visitor center with a museum, theater, and revamped bookstore. The center will celebrate the construction of the memorial and its significance in the fight for Civil Rights. “It is the single most important place where Americans go to exercise their First Amendment rights,” says Mike Litterst, the chief of communications with the National Mall and Memorial Parks.

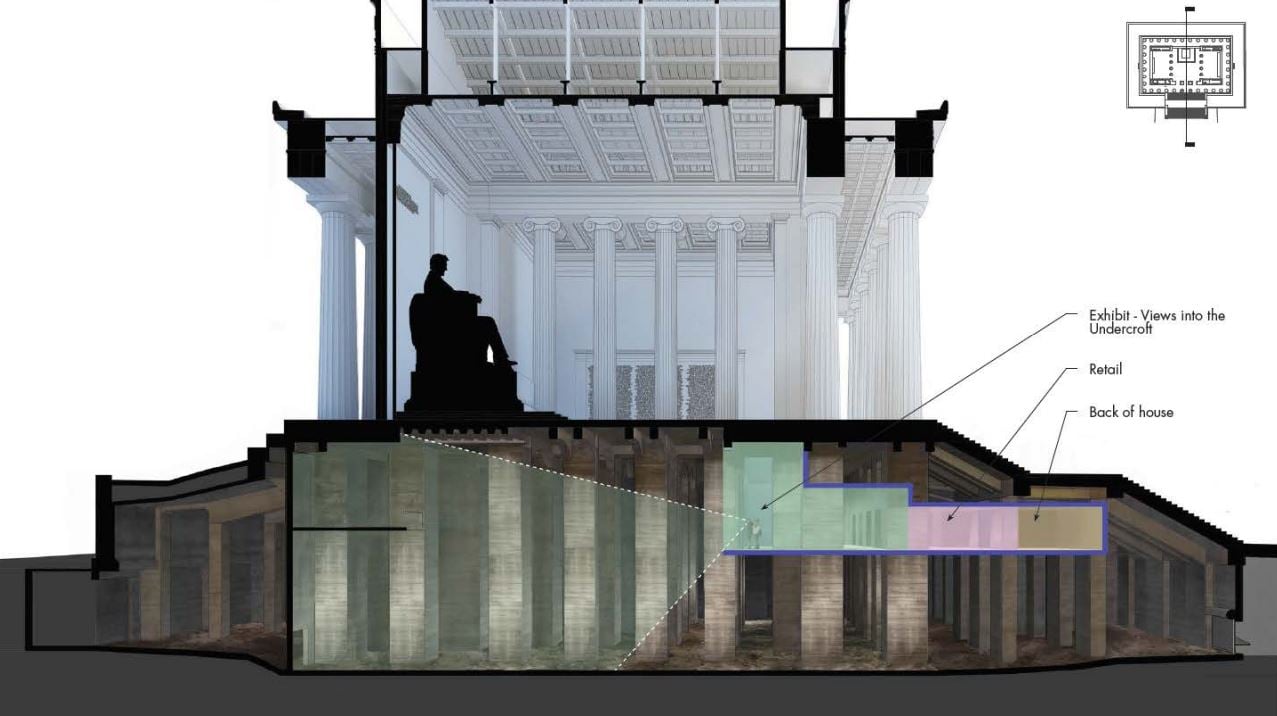

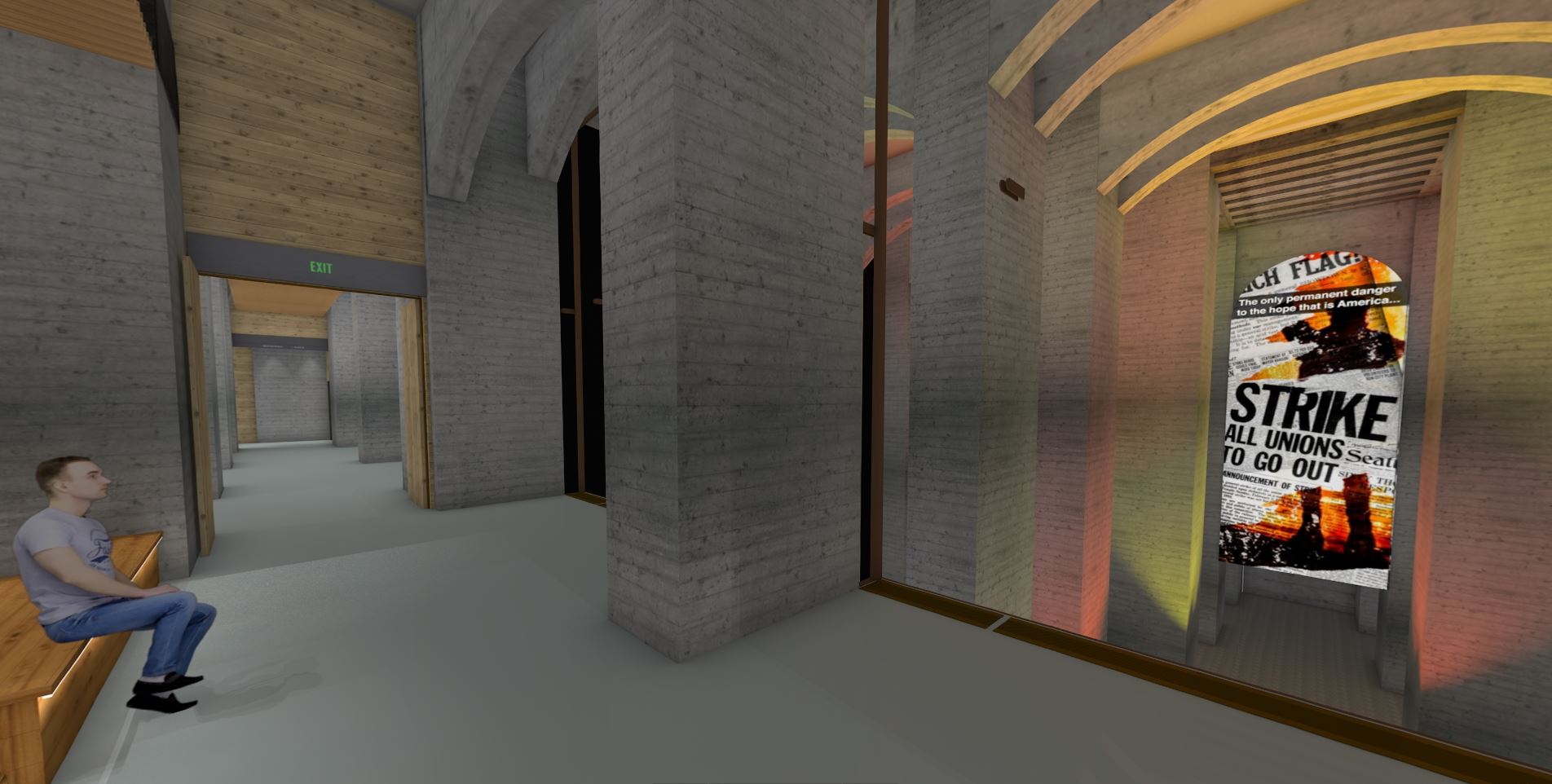

Effectively, Consigli and Quinn Evans, the architecture firm behind the project, are constructing a new building in the undercroft—a glass box perched on a freshly poured concrete slab a story-and-a-half up from the dirt floor. Twenty-two-foot-tall windows will give visitors views of the unfinished section of the undercroft, where films and movies will be projected onto screens and the concrete pillars as part of the museum’s programming. Maybe footage of the Black contralto Marian Anderson, on Easter Sunday 1939, singing “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” as part of a public performance at the memorial, after she was denied access to Constitution Hall because of the color of her skin. Or maybe Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering lines from his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, about transforming “the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.” To prevent condensation from forming on the glass, the panels, fabricated in London, will tie into the electrical system and will be heated. The only changes to the exterior of the memorial: the existing bronze doors on the north and south sides will be enlarged, and a new entry will be added for staff.

Modeled on the Parthenon, the memorial was designed by the architect Henry Bacon and dedicated in 1922, the sculpture of Lincoln carved by the Piccirilli brothers, a team of Italian stonecutters, under the supervision of Daniel Chester French. The idea for the museum first emerged in the 1960s, says Litterst—the brainchild of a Republican Congressman from Iowa, Fred Schwengel, who thought the undercroft could be dedicated to the life of Lincoln. After the idea again gained momentum, David Rubenstein, the businessman and philanthropist, donated $18.5 million to the cause in 2016. (The federal government has pledged $26 million, and the nonprofit National Park Foundation raised $43 million, including Rubenstein’s grant. The addition of a second elevator and extra waterproofing will lift the total cost of the project above $69 million, Litterst says, though he’s uncertain by how much.) Because of the sensitive and historic nature of the site, the design process took seven years; construction started in March 2023.

Much work remains. During the tour, rain fell from the ceiling in the section where new restrooms will be located, because exterior waterproofing was recently stripped away so it can be replaced. Some 400 tons of galvanized rebar were used as part of an effort to shore up the front part of the memorial, making it blast-proof. Small white stalactites hang from the ceiling in areas where water has seeped in over the years; damaged spots will be repaired. Workers have already removed and replaced the steps to the memorial to add waterproofing.

The project is scheduled to be completed in 2026, the year of the nation’s Semiquincentennial, or 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Litterst says. With the hope, of course, that the ribbon cutting comes before July 4th. Giving visitors a chance, finally, to glimpse our nation’s long-hidden basement on the National Mall, and reflect anew on the memorial’s significance. And perhaps on Dr. King’s famous words that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,” as we ponder the journey that lies ahead.