St. Luke’s in Columbia Heights was DC’s first independent Black Episcopal church, built in the 1870s by minister and radical civil-rights leader Alexander Crummell. It’s still standing, a distinctive spot on 15th Street where congregants continue to worship. In 1976, St. Luke’s was designated a National Historic Landmark, but even so, few people who drive by are aware of the place’s significance: It’s the most prominent building designed by the District’s first known African American architect, Calvin T.S. Brent.

Now the DC Preservation League is launching an effort to bring attention to the work and stories of the city’s Black architects—well-known figures like Brent and many other professionals of various renown whose structures have helped define the look of the city. Washington has more than 600 buildings that were constructed or designed by at least 100 Black architects, including notable edifices such as the Twelfth Street YMCA (William Sidney Pittman), the Belgian ambassador’s residence (Julian Abele), and Florida Avenue Baptist Church (Romulus Cornelius Archer Jr.). Yet much of that history—especially when it comes to less famous structures—remains untold and undocumented.

After scoring a grant from the National Park Service in early 2024, the DC Preservation League has tapped the New Jersey design-and-research firm Studio Plat to help steer the project, which will involve both identifying notable buildings and looking into larger aspects such as themes and styles favored, at various points, by Black architects. The plan is to create a searchable database of buildings and also to generate new nominations of Black-designed properties to city and national historic registers.

Studio Plat is run by Princeton professor and architectural historian Jay Cephas, who previously created a national interactive database called the Black Architects Archive. Cephas says DC has the country’s largest concentration of buildings designed by Black architects, in part due to the post-Emancipation era, when the city’s African American population boomed and Black masons, carpenters, and metalworkers flooded the building trades. Many of them stayed and passed on that knowledge; for Cephas, uncovering that timeline of generational skill is the most exciting aspect. “Even in a condition where they’re being excluded through racial discrimination, they create networks among themselves,” he says. “I find that incredibly inspiring.”

Calvin T.S. Brent was able to break into architecture at a time when apprenticeships were the primary way to learn the trade. In 1873, at age 19, he began working as an apprentice for the white-owned architectural firm Plowman and Weightman. Soon he started taking on commissions from middle-class African American clients, eventually designing more than 100 structures throughout all four quadrants of the city before his death in 1899.

But Brent was an outlier. Black architecture in DC didn’t really take off until the 1930s, when Howard University founded its school of architecture. That institution has produced a number of prominent figures, including Albert I. Cassell and Hilyard Robinson, both of whom designed buildings on campus and around the District. Robinson also built the Langston Terrace Dwellings, the city’s first federally funded public-housing complex. “That’s the heart of everything, Howard University and its school of architecture,” says Howard grad Melvin Mitchell, a longtime local architect and author of the book African American Architects. “White architects had the complete run [of things] as far as what an architect is, who’s going to be an architect, and who gets to work.”

For decades, DC’s Black architects had access only to smaller opportunities, especially houses, schools, churches, and businesses in African American neighborhoods. But by the 1980s, practitioners like Paul Devrouax and Marshall Purnell were landing large-scale city and corporate commissions, resulting in projects such as the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in 1982, Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center in 1986, and Studio Theatre in 1987. Today, fans attending games in Capital One Arena and Nationals Park often don’t know that they’re enjoying the work of Black architects.

For every Capital One Arena, there are scores of unheralded structures that deserve to be researched and remembered.

The DC Preservation League hopes to change that with this new initiative. Cephas and his team—which also includes DC filmmaker Michelle A. Jones and architectural-history doctoral candidate Jeremy Lee Wolin—are gearing up for a big undertaking, especially because neighborhoods like Eastland Gardens, Deanwood, and Brookland have large areas where each house is designed by a Black architect. For every Capital One Arena, there are scores of unheralded structures that deserve to be researched and remembered. Doing that work “reconfigures our understanding of the world,” says Cephas. “Making it available to the public can build a kind of national pride of place, where people can understand how the very places around us are a part of their heritage.”

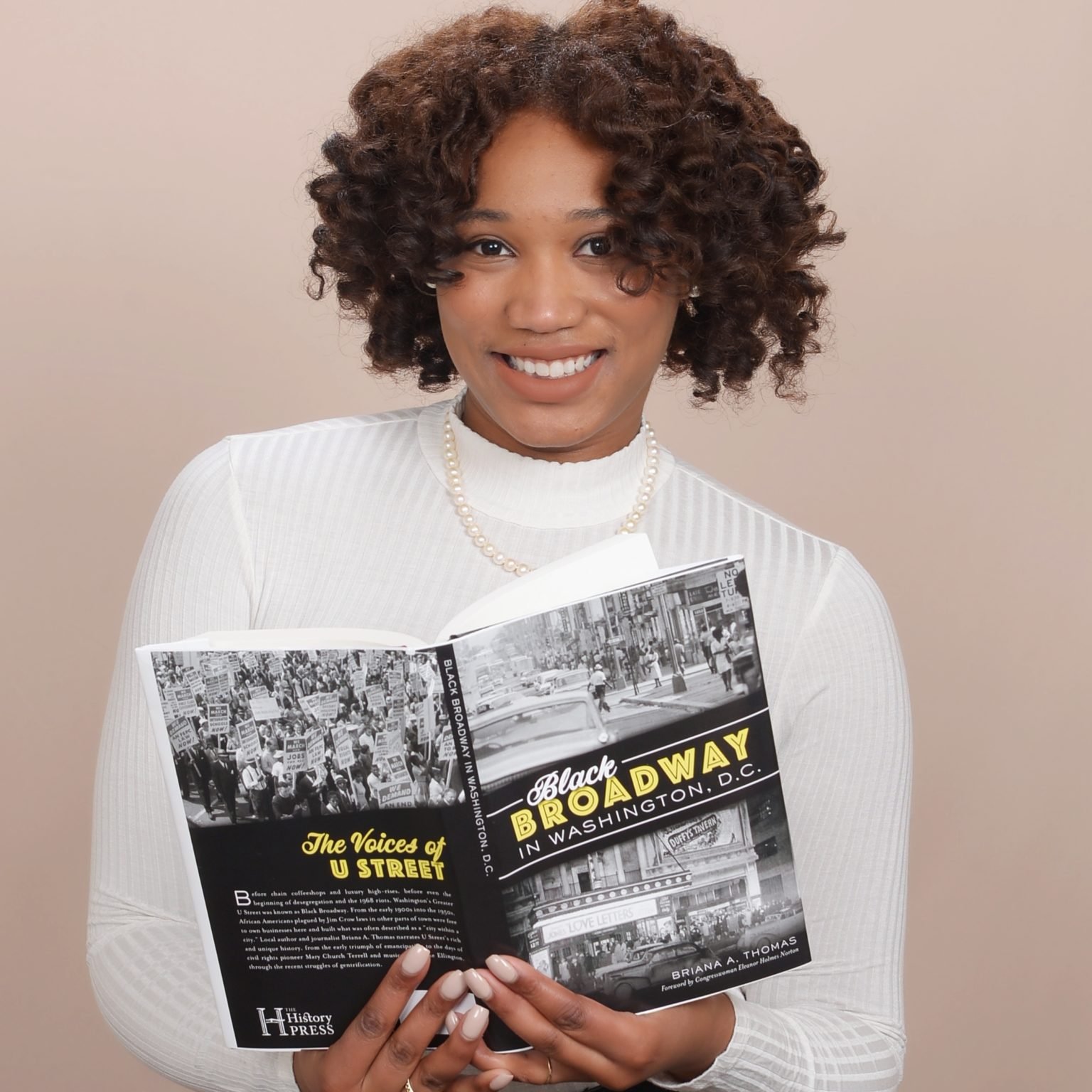

Another goal is to encourage the next generation of Black architects by telling the stories of past professionals who pushed through great challenges to succeed: “The obstacles that were facing them, the discrimination, the segregation, the feeling that they were inferior,” says Jones, whose work includes the documentary Master Builders: Featuring African American Architects in the Nation’s Capital. Today, just 2 percent of licensed architects in the US are Black. Jones wants to give aspiring building designers “the sense that if these individuals could become architects at a time when they had all those things against them, then heck yeah, I can do it. I can persevere.”

Black Architects

Here are just a few of the many Black architects who have helped build the District over the years

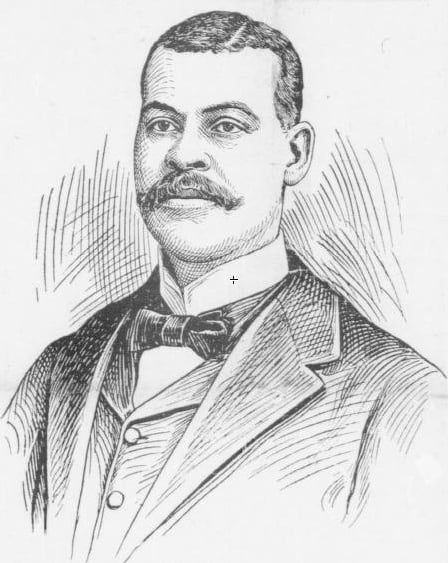

John A. Lankford

1874–1946

Equipped with university degrees in the sciences, mechanics, and law, the master builder moved to Washington in 1902 to finish his most famous project, U Street’s True Reformer Building. He remained in the District and later became the city’s first officially licensed Black architect. He designed many buildings around DC and across the country, including more than 75 churches.

Isaiah T. Hatton

1883–1921

Hatton is known for designing buildings for Black-owned businesses, many of them integral parts of U Street’s Black Broadway. His most notable work includes the Italian Renaissance Revival–style Whitelaw Hotel; DC’s oldest Black bank, Industrial Savings Bank; and Shaw’s historic Southern Aid Society Building–Dunbar Theater.

Hilyard Robinson

1899–1986

A native Washingtonian, the socially conscious modernist headed Howard University’s architecture program and designed 11 structures on campus. One of his buildings was the Langston Terrace Dwellings, an International Style housing project that featured gardens and play spaces and helped inspire the federal government to embrace public housing.

Martha Cassell Thompson

1925–1968

Thompson learned the trade from her father, Albert Cassell, another prominent DC architect. In 1948, she was one of the first Black women to graduate from Cornell University’s school of architecture. An expert in Gothic architecture, she worked as Washington National Cathedral’s chief restoration architect for almost a decade.

Paul S. Devrouax Jr.

1942–2010

With his DC firm, Devrouax+Purnell, the New Orleans–born architect broke racial barriers. He and his business partner, Marshall Purnell, scored major commissions that contributed to DC’s urban revitalization, including the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, Capital One Arena, Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center, and Nationals Park.

St. Luke’s in Columbia Heights was DC’s first independent Black Episcopal church, built in the 1870s by minister and radical civil-rights leader Alexander Crummell. It’s still standing, a distinctive spot on 15th Street where congregants continue to worship. In 1976, St. Luke’s was designated a National Historic Landmark, but even so, few people who drive by are aware of the place’s significance: It’s the most prominent building designed by the District’s first known African American architect, Calvin T.S. Brent.

Now the DC Preservation League is launching an effort to bring attention to the work and stories of the city’s Black architects—well-known figures like Brent and many other professionals of various renown whose structures have helped define the look of the city. Washington has more than 600 buildings that were constructed or designed by at least 100 Black architects, including notable edifices such as the Twelfth Street YMCA (William Sidney Pittman), the Belgian ambassador’s residence (Julian Abele), and Florida Avenue Baptist Church (Romulus Cornelius Archer Jr.). Yet much of that history—especially when it comes to less famous structures—remains untold and undocumented.

After scoring a grant from the National Park Service in early 2024, the DC Preservation League has tapped the New Jersey design-and-research firm Studio Plat to help steer the project, which will involve both identifying notable buildings and looking into larger aspects such as themes and styles favored, at various points, by Black architects. The plan is to create a searchable database of buildings and also to generate new nominations of Black-designed properties to city and national historic registers.

Studio Plat is run by Princeton professor and architectural historian Jay Cephas, who previously created a national interactive database called the Black Architects Archive. Cephas says DC has the country’s largest concentration of buildings designed by Black architects, in part due to the post-Emancipation era, when the city’s African American population boomed and Black masons, carpenters, and metalworkers flooded the building trades. Many of them stayed and passed on that knowledge; for Cephas, uncovering that timeline of generational skill is the most exciting aspect. “Even in a condition where they’re being excluded through racial discrimination, they create networks among themselves,” he says. “I find that incredibly inspiring.”

Calvin T.S. Brent was able to break into architecture at a time when apprenticeships were the primary way to learn the trade. In 1873, at age 19, he began working as an apprentice for the white-owned architectural firm Plowman and Weightman. Soon he started taking on commissions from middle-class African American clients, eventually designing more than 100 structures throughout all four quadrants of the city before his death in 1899.

But Brent was an outlier. Black architecture in DC didn’t really take off until the 1930s, when Howard University founded its school of architecture. That institution has produced a number of prominent figures, including Albert I. Cassell and Hilyard Robinson, both of whom designed buildings on campus and around the District. Robinson also built the Langston Terrace Dwellings, the city’s first federally funded public-housing complex. “That’s the heart of everything, Howard University and its school of architecture,” says Howard grad Melvin Mitchell, a longtime local architect and author of the book African American Architects. “White architects had the complete run [of things] as far as what an architect is, who’s going to be an architect, and who gets to work.”

For decades, DC’s Black architects had access only to smaller opportunities, especially houses, schools, churches, and businesses in African American neighborhoods. But by the 1980s, practitioners like Paul Devrouax and Marshall Purnell were landing large-scale city and corporate commissions, resulting in projects such as the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in 1982, Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center in 1986, and Studio Theatre in 1987. Today, fans attending games in Capital One Arena and Nationals Park often don’t know that they’re enjoying the work of Black architects.

For every Capital One Arena, there are scores of unheralded structures that deserve to be researched and remembered.

The DC Preservation League hopes to change that with this new initiative. Cephas and his team—which also includes DC filmmaker Michelle A. Jones and architectural-history doctoral candidate Jeremy Lee Wolin—are gearing up for a big undertaking, especially because neighborhoods like Eastland Gardens, Deanwood, and Brookland have large areas where each house is designed by a Black architect. For every Capital One Arena, there are scores of unheralded structures that deserve to be researched and remembered. Doing that work “reconfigures our understanding of the world,” says Cephas. “Making it available to the public can build a kind of national pride of place, where people can understand how the very places around us are a part of their heritage.”

Another goal is to encourage the next generation of Black architects by telling the stories of past professionals who pushed through great challenges to succeed: “The obstacles that were facing them, the discrimination, the segregation, the feeling that they were inferior,” says Jones, whose work includes the documentary Master Builders: Featuring African American Architects in the Nation’s Capital. Today, just 2 percent of licensed architects in the US are Black. Jones wants to give aspiring building designers “the sense that if these individuals could become architects at a time when they had all those things against them, then heck yeah, I can do it. I can persevere.”

Black Architects

Here are just a few of the many Black architects who have helped build the District over the years

John A. Lankford

1874–1946

Equipped with university degrees in the sciences, mechanics, and law, the master builder moved to Washington in 1902 to finish his most famous project, U Street’s True Reformer Building. He remained in the District and later became the city’s first officially licensed Black architect. He designed many buildings around DC and across the country, including more than 75 churches.

Isaiah T. Hatton

1883–1921

Hatton is known for designing buildings for Black-owned businesses, many of them integral parts of U Street’s Black Broadway. His most notable work includes the Italian Renaissance Revival–style Whitelaw Hotel; DC’s oldest Black bank, Industrial Savings Bank; and Shaw’s historic Southern Aid Society Building–Dunbar Theater.

Hilyard Robinson

1899–1986

A native Washingtonian, the socially conscious modernist headed Howard University’s architecture program and designed 11 structures on campus. One of his buildings was the Langston Terrace Dwellings, an International Style housing project that featured gardens and play spaces and helped inspire the federal government to embrace public housing.

Martha Cassell Thompson

1925–1968

Thompson learned the trade from her father, Albert Cassell, another prominent DC architect. In 1948, she was one of the first Black women to graduate from Cornell University’s school of architecture. An expert in Gothic architecture, she worked as Washington National Cathedral’s chief restoration architect for almost a decade.

Paul S. Devrouax Jr.

1942–2010

With his DC firm, Devrouax+Purnell, the New Orleans–born architect broke racial barriers. He and his business partner, Marshall Purnell, scored major commissions that contributed to DC’s urban revitalization, including the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, Capital One Arena, Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center, and Nationals Park.

This article appears in the January 2025 issue of Washingtonian.