Contents

Fifty years ago this June, Washington hosted its first official Pride. Held in front of the gay-and-lesbian bookstore Lambda Rising, the event was both celebration and statement. In a photo from the day, the store’s founder holds a DC Council “Gay Pride Day” proclamation while a council member looks on. Standing nearby is legendary activist Frank Kameny, a Harvard-trained astronomer whose lifelong crusade began when he was fired from his federal job for being gay.

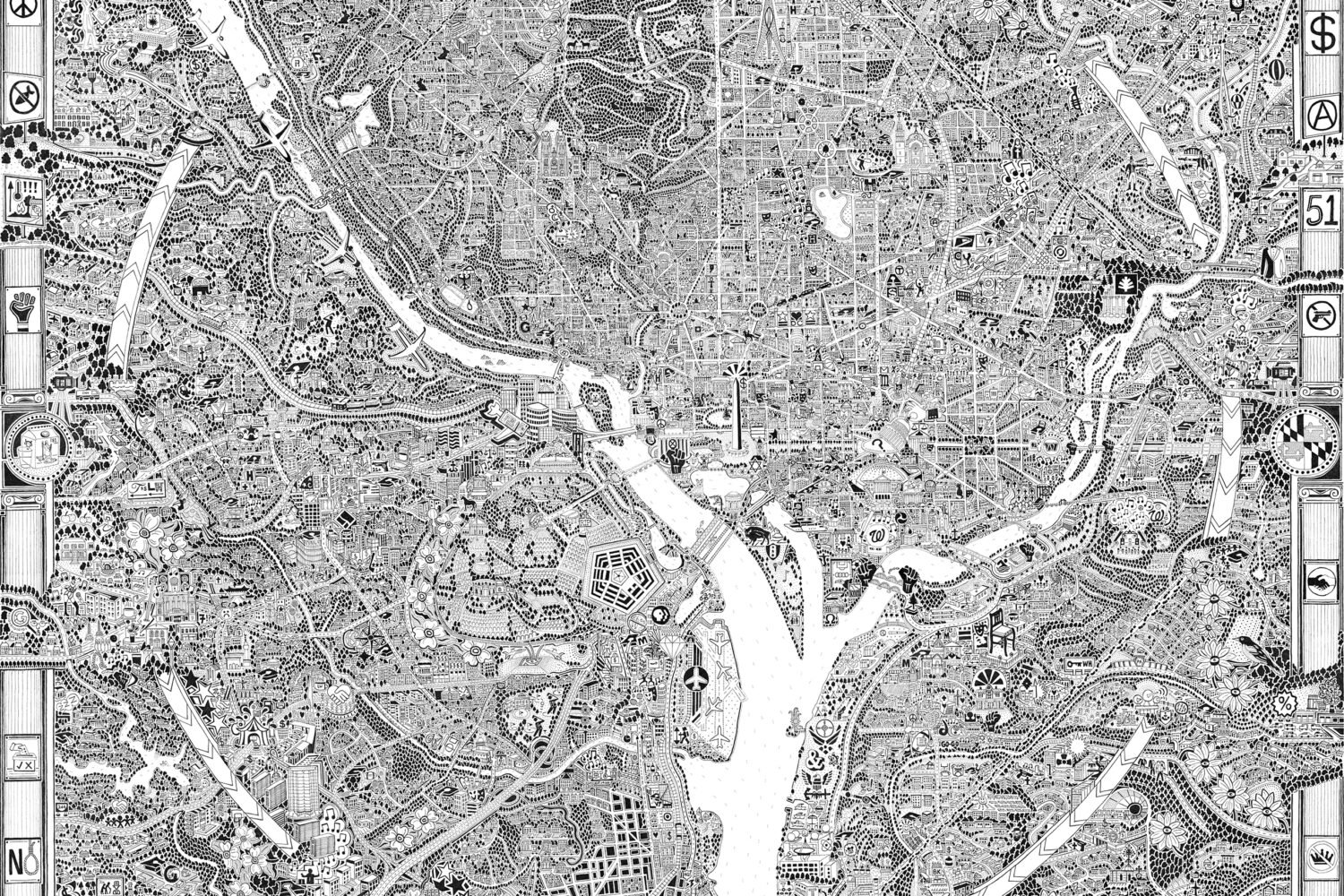

In the nation’s capital, neither politics nor culture sits downstream from the other. The two swirl and flow together, through a government that reflects the country and shapes it. Among the queerest of American cities culturally, DC is also the epicenter of so many battles over LGBTQ+ rights. While Senator Joseph McCarthy was ranting about “perverts” in the State Department, gay Black men found safety at the Nob Hill bar just a few miles away. While President Reagan struggled to say “gay” in his rare statements on the AIDS crisis, locals kicked off the beloved annual High Heel Race. While President Trump promised to end Kennedy Center “drag shows targeting our youth,” protesters marched in gender-fluid, Technicolor style.

Our city has been home to the Lavender Scare and America’s first known drag queen; police assaults on gay men and ACT UP protests at the White House; transgender military-service bans and Congresswoman Sarah McBride, the first openly trans House member. We embody the contradictions and conflicts—and the change. As the world joins us to celebrate a half century of Pride, it’s time to look back on where we’ve been, the better to see where we might go next.

-

1896

Back to TopAn Unspeakable Offense

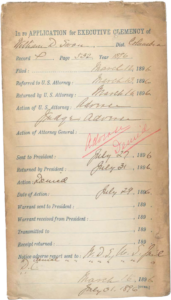

Photograph courtesy of James Gardiner Collection/Wellcome Library. In March 1896, the US attorney general for DC weighed in on a clemency petition for a prisoner sentenced to 300 days in jail, nominally for running a brothel: “While the charge of keeping a disorderly house does not on its face differ from other cases in which milder sentences have been imposed, the prisoner was in fact convicted of one of the most horrible and disgusting offences known to the law; an offence so disgusting that it is unnamed.”

This unspeakable offense was almost certainly drag. The prisoner, William Dorsey Swann, born into slavery in Hancock, Maryland, was a host of drag balls, attended by a large, mixed-race community of men in DC. “They nearly all had on low neck and short sleeve silk dresses, several of them with trains,” wrote the Washington Critic in 1887, describing an earlier police raid on a ball attended by Swann. Another article called Swann a ball’s “queen,” an epithet he also adopted, becoming history’s first self-described drag queen. Once, according to author Channing Joseph, Swann was said to have charged at the police in defense of his community—an act later echoed at New York City’s Stonewall Inn and in other times and places.

Photograph courtesy of National Archives. Swann held a strong public reputation through multiple arrests. His clemency petition (below), ultimately rejected by President Grover Cleveland, was signed by 30 supporters and described him as a “hard-working and industrious man” employed by General William Dudley, an important official in post–Civil War Washington. Swann’s dual existence would be familiar to many queer Washingtonians before and since—particularly drag artists, who have long ping-ponged between acceptance and backlash.

At the time of Swann’s parties, drag—loosely defined as a theatrical performance of a gender one wasn’t born into—was shifting from a popular vaudeville act to an art form enjoyed by well-heeled straight audiences, particularly during the “pansy craze” of the 1920s and ’30s. The Jewel Box Revue, an integrated all-drag troupe that traveled the world in the 1940s and ’50s, at one point did a stint at the upscale DC dinner theater Casino Royal. Local artists hung on through police crackdowns on gay men in the 1950s, and by the 1960s and ’70s, there was a thriving scene of drag houses and regular balls. During the AIDS crisis, the community supported the afflicted; by the 1990s, DC was hosting some 40 shows weekly. As drag again faces backlash, artists may take courage from Swann’s story.

-

Back to Top

December 7, 1910

Back to TopA statue of Prussian general Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben is unveiled in Lafayette Park, a longtime cruising ground for the city’s gay men. Believed to have been gay, von Steuben fought with the Americans in the Revolutionary War. That same year, DC also erects a statue of Casimir Pulaski, a Polish Revolutionary War general believed to have been intersex.

-

Back to Top

1920s–’30s

Back to TopAt 1461 S Street, NW, poet, playwright, and anti-lynching activist Georgia Douglas Johnson hosts Saturday-night salons for many of the queer Black luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, Angelina Weld Grimké, Richard Bruce Nugent, and Alain Locke.

-

Back to Top

1950

Back to TopThe Lavender Scare

Photograph by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images. In February 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy bragged about having a list of Communists working for the State Department—two of them gay men. That same month, a State Department official told the Senate that he had recently fired 91 employees for being gay. The official rationale was that gays were a “security risk” and vulnerable to blackmail. But there was also clear revulsion—gays were seen as limp-wristed, contrary to nature and God, somehow just wrong. Republican senator Kenneth Wherry asked, “Can you think of a person who could be more dangerous to the United States of America than a pervert?”

Politicians looking for easy scapegoats whipped this prejudice into a mass witch hunt, with Wherry co-leading an investigation to root out gays in government and President Eisenhower signing a 1953 executive order that barred anyone with “sexual perversions” from federal employment. Aided by his deputy Roy Cohn and FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, McCarthy launched an anti-gay purge whose effects are still felt today. (Notably, all three men were themselves dogged by gay rumors. Cohn, an ineffectively closeted gay man, would later die of AIDS.)

Although “security risk” firings petered out over time, Eisenhower’s ban wasn’t officially lifted until the 1990s. At least 5,000 queer people, mostly gay men, lost their jobs, and an unknown number were unable to serve in the first place. Being fired as a “security risk” also meant being outed to the broader community, sometimes with shattering results: Some targeted federal workers lost their families, while others committed suicide.

In a twist McCarthy never dreamed of, the purge fed directly into the birth of the modern gay-rights movement. Frank Kameny, a military veteran and Harvard PhD in astronomy who was hired in 1957 by the Army Map Service, lost his job following accusations of homosexual behavior. Refusing to depart in shame, he appealed his firing and took his case to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear it. Kameny then founded the DC branch of the Mattachine Society, which in 1965 organized the first gay-rights protest in District history. Ten men and women—including Lilli Vincenz, cofounder of the newspaper that became the Washington Blade—marched in front of the White House, demanding the end of the federal ban.

The protests spread to other cities, and Kameny became one of the most respected gay activists in the country. Many of his goals—including an end to anti-sodomy laws and the removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM—took years to achieve. But his defiance laid the groundwork for a more tolerant future.

-

Back to Top

1953

Photograph by Rainbow History Project Digital Collections. Nob Hill, one of the longest-operating gay bars in the country (today the site of Wonderland Ballroom) opens. Initially a private social club that will become a bar in 1957 and stay in business until 2004, it mostly serves African American men, including Howard University students.

-

Back to Top

Fall 1961

Back to TopAccording to the Rainbow History Project, Alan Kress, a drag queen performing under the name Liz Taylor, organizes the country’s first annually scheduled drag competition, the Academy Awards of Washington. The Academy—as it will become known after Hollywood’s Academy Awards threatens to sue—later uses its fundraising clout to support drag artists affected by the AIDS crisis.

-

Back to Top

1970s

Back to TopThis Bold House

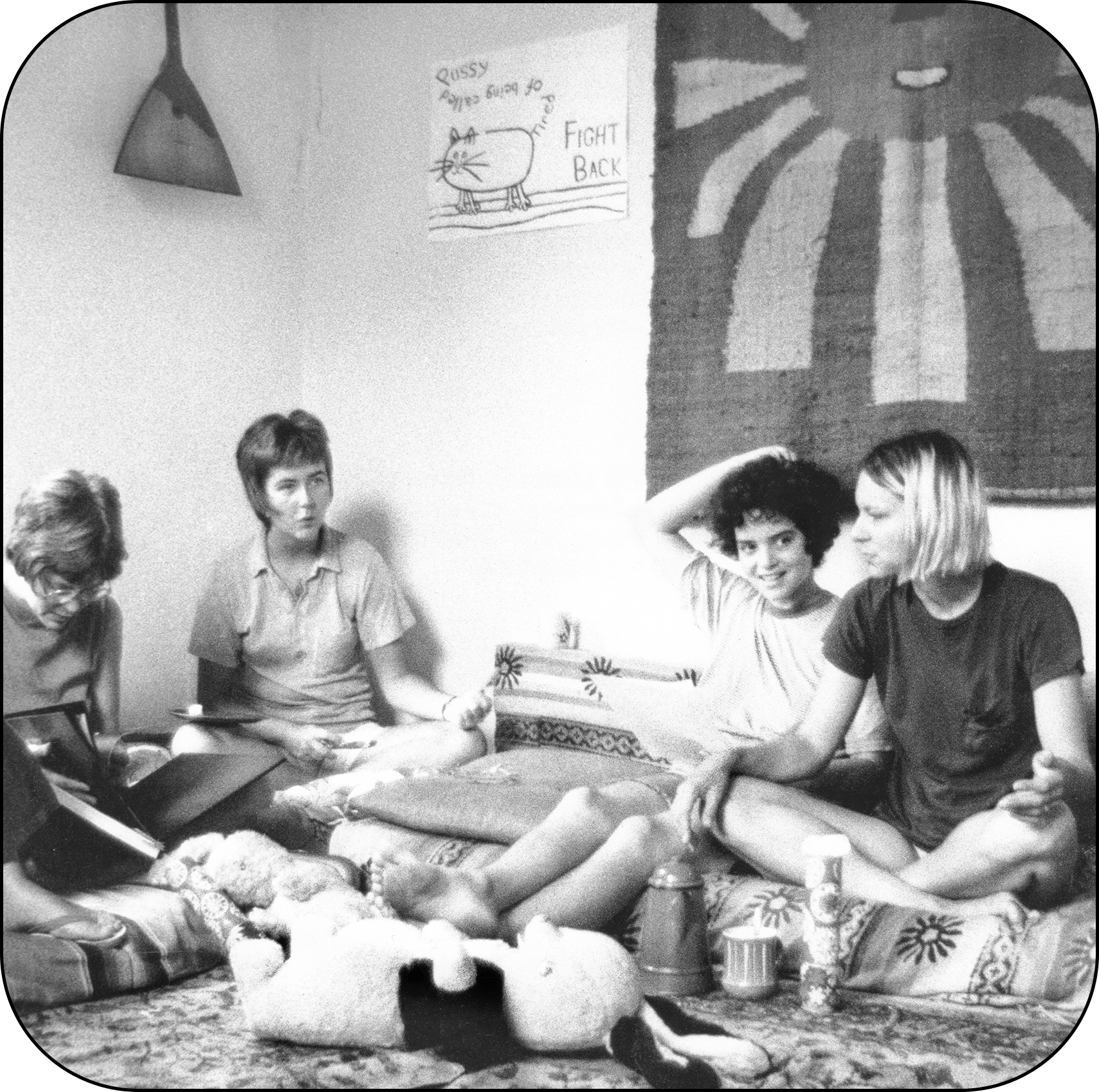

Photograph by JEB (Joan E. Biren). Many DC group-house residents have believed they would change the world—but the Furies Collective, based at 219 11th Street, Southeast, from 1971 to ’72, actually did. One of many communal-living experiments in 1970s Washington, the Furies were a group of 12 lesbian feminists, all radicals with extensive organizing backgrounds, plus three children and a cat named Baby Jesus. They shared everything, slept on an assemblage of mattresses on the floor, led political-theory workshops, taught mechanics classes to women, and published a regular newspaper, the Furies, which was sold at women’s bookstores across the country. “We are committed to ending all oppressions by attacking their roots—male supremacy,” they wrote in the first issue.

At the time, the nascent feminist movement wasn’t welcoming to queer women. National Organization for Woman president Betty Friedan referred to a “lavender menace,” and some feared that associating with lesbians would undermine the movement’s credibility by making feminists look like “man-haters.” In protest, a group called the Radicalesbians led a brief hijacking of the NOW-led Second Congress to Unite Women in 1970, wearing T-shirts that read “Lavender Menace” and demanding that NOW embrace lesbians. Rita Mae Brown, who later became a bestselling novelist and author of the lesbian classic Rubyfruit Jungle, was one of the protest’s architects and a key figure in the Furies Collective.

While the Furies lasted only 18 months before splintering, their influence endures. Members became academics, writers, political organizers, and publishers. The ideas advanced in their magazine remain relevant, from the proper role of men (and, for some modern-day radical feminists, transgender women) in women’s spaces to the relationship of feminism to broader social struggles around sexuality, gender, race, and class. Perhaps most important, the group showed queer women that it was possible not only to dream of a better world but also to create one together. As Brown wrote in her memoir, the collective “alerted other gay women to the shattering knowledge that they weren’t alone.”

-

Back to Top

June 22, 1975

Back to TopDeacon Maccubin, founder of Lambda Rising bookstore in Dupont Circle, holds DC’s first annual Pride event, the Gay Pride Party, inspired by the parades in New York City that followed the Stonewall riots of 1969.

-

Back to Top

1978

Back to TopWhitman-Walker Clinic—an LGBTQ+ health nonprofit named for queer poet Walt Whitman and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, a 19th-century abolitionist and surgeon who preferred male attire—is incorporated. Whitman-Walker will later be on the front line of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in DC, providing services including testing, treatment, housing, and legal help.

-

Back to Top

October 14, 1979

Back to Top

Photograph by AP Images. The first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights features some 100,000 participants—led by a group of lesbians of color called the Salsa Soul Sisters—marching past the White House to the National Mall and shouting, “We are everywhere!” Three more marches will be held in 1987 (when the AIDS Memorial Quilt is first exhibited on the Mall), 1993, and 2000.

-

Back to Top

1980s

Back to TopResting in Power

While many gays in the military were forcibly outed, Leonard Matlovich, an Air Force technical sergeant and Purple Heart recipient, was the first one known to out himself in protest—working in collaboration with the American Civil Liberties Union and activist Frank Kameny and, in 1975, appearing on the cover of Time magazine. During the legal battle over his ensuing discharge, Matlovich lived across from the historic Congressional Cemetery in Southeast DC and was pleased to learn that Peter Doyle, believed to be Walt Whitman’s lover, was buried there. (So was Alain Locke, the gay “dean of the Harlem Renaissance,” who frequented Georgia Douglas Johnson’s salons.) Matlovich bought a double plot in the cemetery a few feet away from the graves of J. Edgar Hoover and his longtime deputy and rumored lover, Clyde Tolson. “It was kind of a middle finger to Hoover,” the cemetery’s president, Paul Williams, told the Washington Post in 2021.

Matlovich died of AIDS in 1988, having designed his own Congressional Cemetery headstone in a final gesture of defiance. The text reads, “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one,” next to two pink triangles, one upside-down: the Nazi symbol for homosexuals, reappropriated in its inverted form as a symbol of queer resistance. Over time, Matlovich’s grave has become a pilgrimage site: Couples have married there, and a number of other prominent LGBTQ+ figures, including seminal lesbian activists Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen, are buried nearby in what’s now known as the “gay corner”—right next to Hoover and Tolson. A memorial tribute to Kameny sits near Matlovich’s grave, inscribed with the slogan “Gay is Good.”

-

Back to Top

October 31, 1986

JR’s Bar and Grill in Dupont Circle holds the first-ever High Heel Race, with 25 drag queens racing to Annie’s Paramount Steakhouse and back. In 1991, the race is canceled after neighbors complain. The community gathers anyway, and police make arrests and beat them with nightsticks. The race has only grown since then, and it’s now a major annual event sponsored by the city.

-

Back to Top

1991

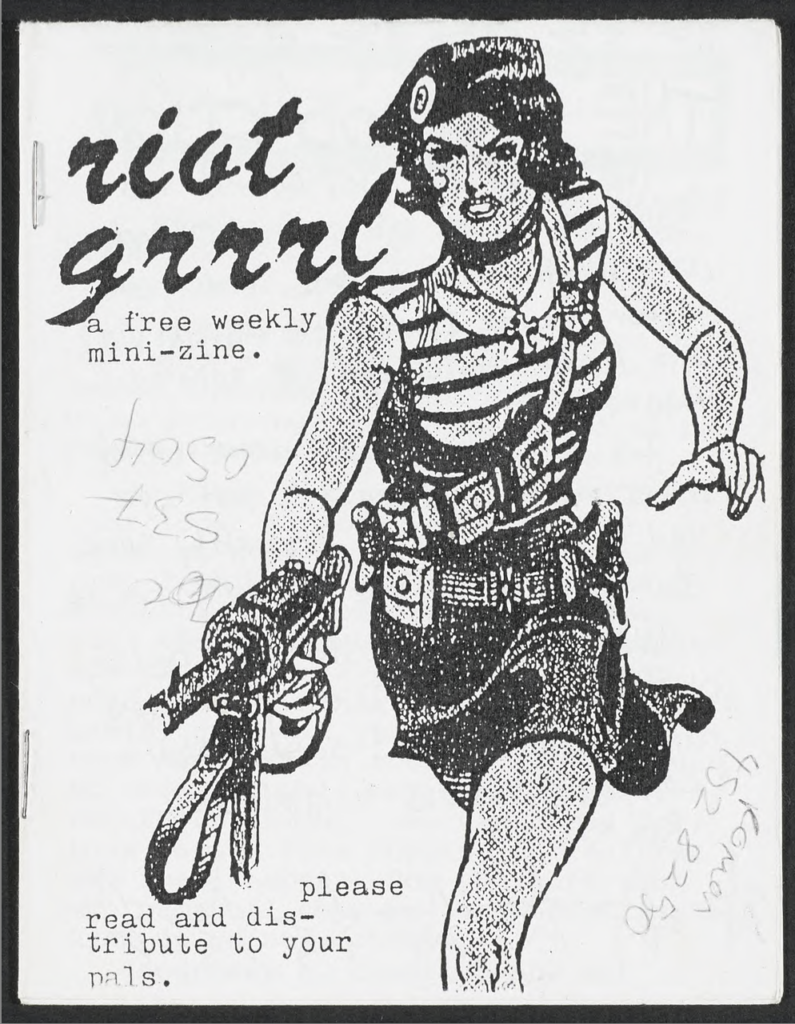

Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress. The first issue of Riot Grrrl, a punk zine that will help kick off a queer-friendly feminist movement, is published by a team of women working out of a group house in Mount Pleasant.

-

Back to Top

1992

Back to TopActing Up

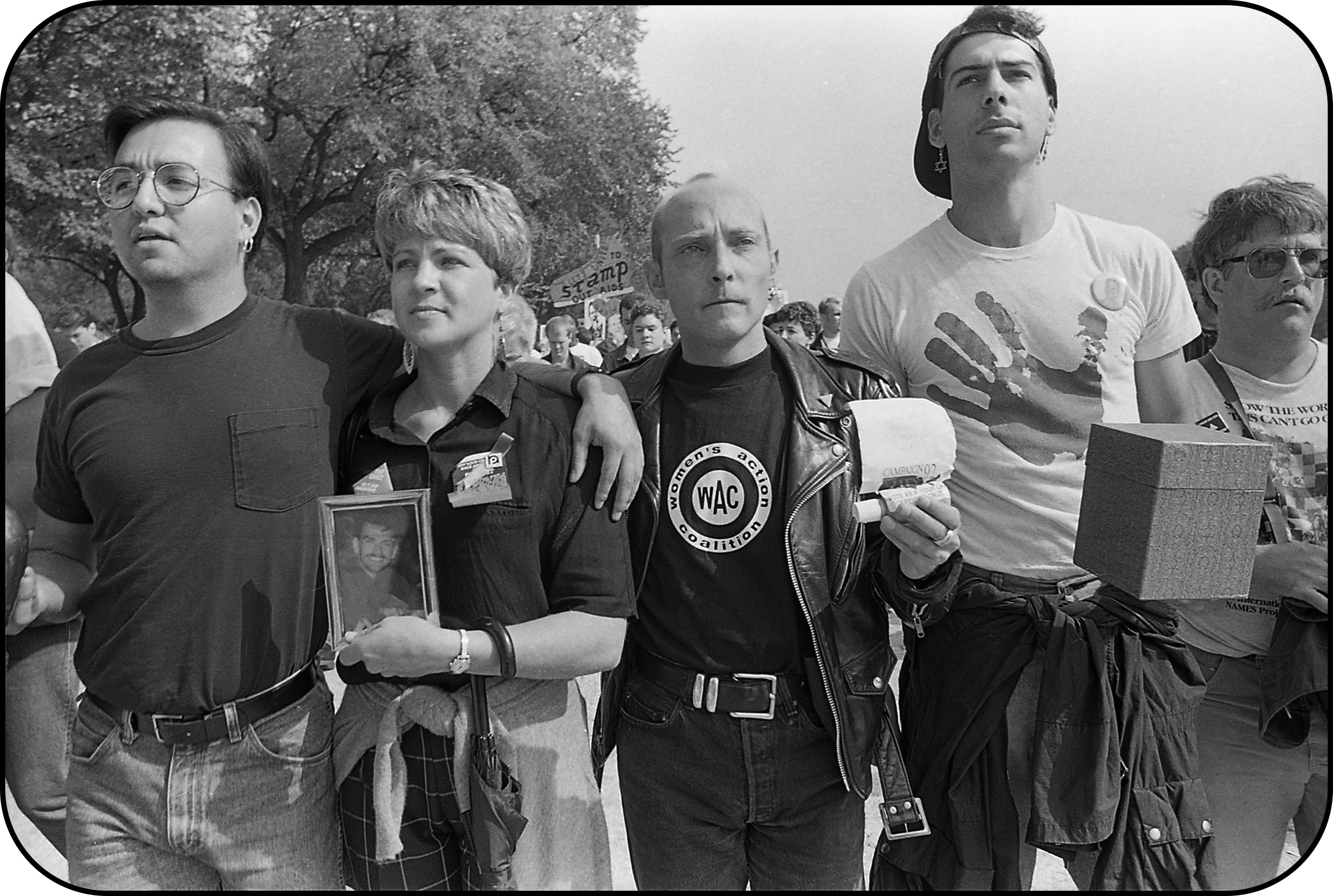

Photograph by Meg Handler. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) protesters threw ashes of loved ones who had died of AIDS over the White House fence in an effort to draw attention to the continued plight of AIDS patients. “If you won’t come to the funeral,” one demonstrator said about President George H.W. Bush, “we’ll bring the funeral to you.”

-

Back to Top

1993

Back to TopPresident Clinton signs into law “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” allowing gays and lesbians to serve in the armed forces, provided they don’t display “a propensity or intent to engage in homosexual acts.” Three years later, he signs the Defense of Marriage Act, defining marriage as existing between a man and a woman. The two laws are eventually defeated in 2011 and 2013.

-

Back to Top

August 7, 1995

Back to TopWhen Tyra Hunter, a Black trans woman, gets into a car accident in Southeast DC, paramedics on the scene ignore and mock her, failing to provide treatment that could save her life. Hunter’s death ignites protests and a closer attention to how emergency-service workers respond to transgender patients.

-

Back to Top

December 15, 1997

Back to TopRepublican David Catania is sworn in as the DC Council’s first openly gay member. He later leaves the Republican Party over its attempt to amend the Constitution to ban gay marriage.

-

Back to Top

2015

Back to TopFreed Love

Photograph by Jeff Malet. On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges officially legalized same-sex marriage in the United States—catching the nation up to DC, where it had been legal since late 2009. Under rainbow flags and balloons, queer couples and their families and supporters cheered, wept, and kissed on the steps of the court, while that night President Obama illuminated the White House in rainbow colors. Across the Washington area and elsewhere, couples who in some cases had been together for decades and sometimes shared children or even grandchildren were finally free to exercise a right that had long been unthinkable.

-

Back to Top

June 30, 2016

Back to Top

Photograph by Amy Sussman/Getty Images. The Pentagon allows transgender people to serve openly in the military. Bree Fram (left), an Air Force officer working in the Pentagon, comes out as trans the same day. President Trump will reverse the policy in 2019; Biden will reinstate it in 2021; Trump will reverse it yet again in 2025.

-

Back to Top

2016

Back to TopPhase One, DC’s longest-running lesbian bar, closes its doors during a time when gentrification and rising costs have caused many LGBTQ+ establishments to shutter. Open since 1970, Phase One was the final survivor of the “Gay Way,” a strip on Eighth Street, Southeast, that was near the Furies Collective house and had been home to numerous gay and lesbian bars since the late 1960s.

-

Back to Top

June 1, 2024

Back to Top

Photograph by Fadil Berisha. Bailey Anne becomes the first-ever transgender Miss Maryland USA and only the second transgender contestant in the Miss USA competition.

-

Back to Top

2025

Back to TopMarching Onward

Photograph by DuHon Photography. LGBTQ+ groups concerned over the Trump administration’s attacks on drag artists—and queer people generally—staged a “March for Drag” that culminated at the Kennedy Center. “This evening as we walk down the streets of our capital city, we are walking in the footsteps of our queer ancestors who fought tooth and nail for every right that we have ever attained,” said drag activist Sister Sybil Liberties.

This article appears in the June 2025 issue of Washingtonian.