High schoolers may no longer be able to sneakily text under their desks. On Friday, DC Public Schools (DCPS) announced a policy to ban personal cellphone use, starting in the 2025-2026 school year. Here’s what to know:

Proponents say the policy will make students more focused

“We’ve been recognizing the body of research around this issue that suggests smartphone use and devices have been detrimental to the school environment,” says Lewis Ferebee, the Chancellor of DCPS.

Nationally, about three-quarters of high school teachers and a third of middle school teachers say distractions from cellphones are a “major problem” in their classroom.

Supporters of the new policy hope that cellphone restrictions will help students focus and improve upon low test scores that have not fully recovered from a decline during the pandemic. Only 34 percent of DC students meet or exceed grade-level expectations in reading, and only 23 percent meet or exceed expectations in math.

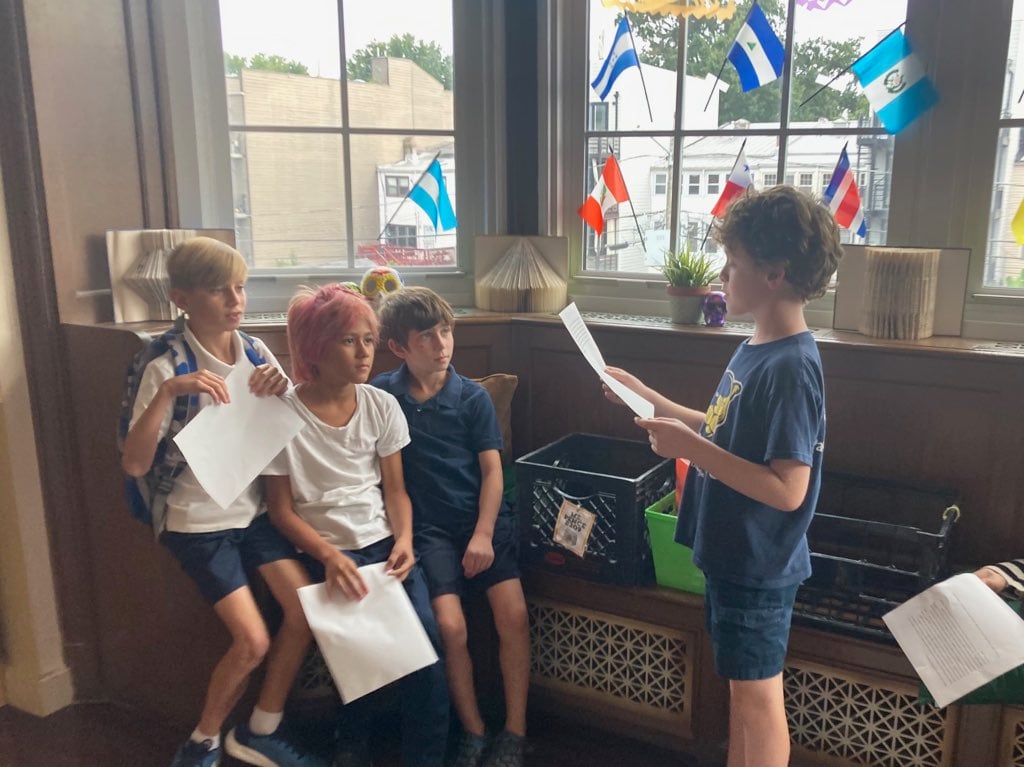

Ban proponents also hope that it will encourage students to be more social in the off-screen world. “Removing distracting devices during the school day will better equip our students to focus, empower our teachers to teach, and ensure that our kids are engaging with one another in person which will benefit them and their outcomes for years to come,” says DC Councilmember Brooke Pinto, who in January introduced a bill to ban cellphone use in schools.

Opponents say banning phones is a safety problem

Some worry that bans prevent students from being able to communicate with their families during emergencies—including, for example, school shootings. Many students and parents expressed that concern to the Council during discussions of Pinto’s bill.

“Students should not be cut off from the ability to contact their families or authorities,” Tiffani Nichole Johnson, a parent and the 4B06 ANC Commissioner, said in testimony submitted to the Council in March. “Following a shooting outside of my daughter’s school, it was my ability to text her that I was assured she was safe. It took DCPS hours (after the conclusion of the school day) to even acknowledge that the shooting had occurred.”

DCPS maintains that students should not be focusing on contacting their loved ones during emergencies. The new policy, obtained by Washingtonian, reads, “During school-based emergencies, families should refrain from contacting their student directly as student safety is best supported when they can give their complete attention to the important instructions provided by school staff.”

Kera Tyler, Chief of External Affairs for DCPS, says that schools have a “robust” system for communicating with parents and families during emergencies that is safer and more effective than students trying to reach their families on their own: “Parents are alerted via text messages during the evacuation or whatever change in the operating status—that they’re going on alert, they’re going under lockdown—those messages are sent as close to real-time as possible.”

Nationally and in DC, many schools have already implemented similar policies

Personal phone use already has been banned in DC middle schools for two years, starting in the 2023-2024 school year, and several high schools have similar policies.

The District-wide change is part of a national shift: 25 states have already passed laws regulating students’ use of phones during the school day, and more than three in four schools nationwide say they ban cellphone use for non-academic purposes—though these policies are often unenforced.

Teens are sneaky. How will schools enforce this?

The new policy requires that students’ cellphones are not accessible to them during the school day—they can’t, for example, keep their phones in their pockets. Beyond that, the policy leaves much of the enforcement and storage decisions up to individual schools.

“We will give schools autonomy to implement their new policies for their school community, so it will look different from school to school,” Ferebee says. “The high schools that are currently implementing this have a number of different strategies, from lockers to pouches to other means for storing devices.”

The policy includes some exceptions for field trips, educational activities using devices, and students who need personal devices as an accommodation for a disability or medical need.