t’s a springtime Thursday night at Nanny O’Brien’s Irish Pub in Northwest DC, and up on the TVs, the University of Maryland men’s basketball team is struggling against the University of Florida. The bar is stuffed with revelers eating chicken wings and drinking beer. Given that Americans will wager an estimated $3.1 billion on college basketball’s championship tournament this year, it’s a fair bet that at least some of them are fretting about what they have riding on the game.

Pratik Chougule is thinking about wagers, too—just not on sports. “I don’t understand how we can have this quasi-national religion in which everyone in their 9-to-5 jobs, when they should be working, is checking their March Madness bracket,” he says over the din. “Why is that okay, but a betting market on something as important as a piece of legislation or an election outcome, that is the thing we really police?”

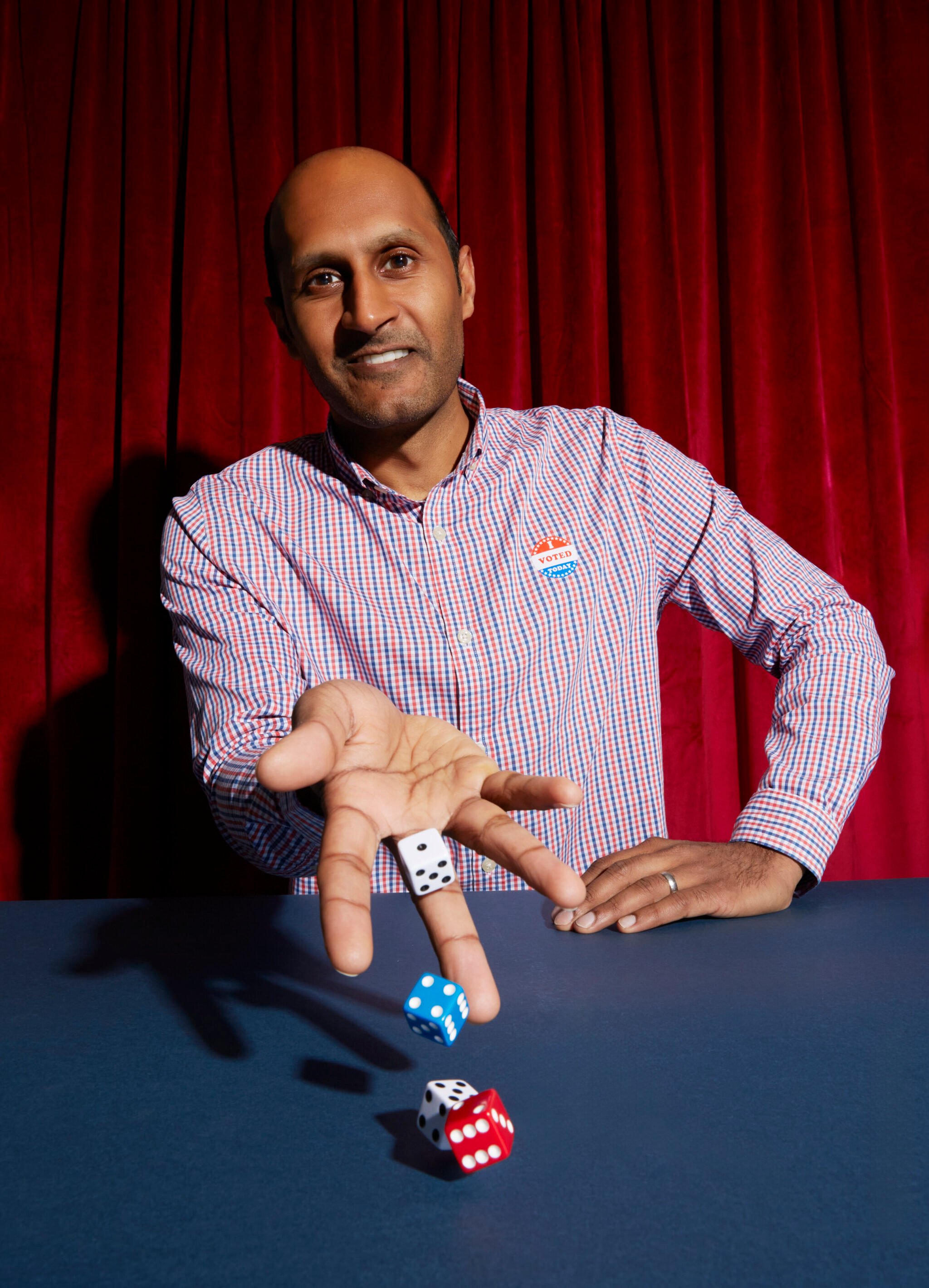

A 39-year-old lawyer in Northern Virginia, Chougule is one of the country’s most outspoken advocates for political betting—a relatively small, definitely growing, questionably legal pastime that is, well, exactly what it sounds like. Just as sports fans wager on the outcome of tennis matches and Washington Commanders games, people like Chougule gamble on who will win electoral races.

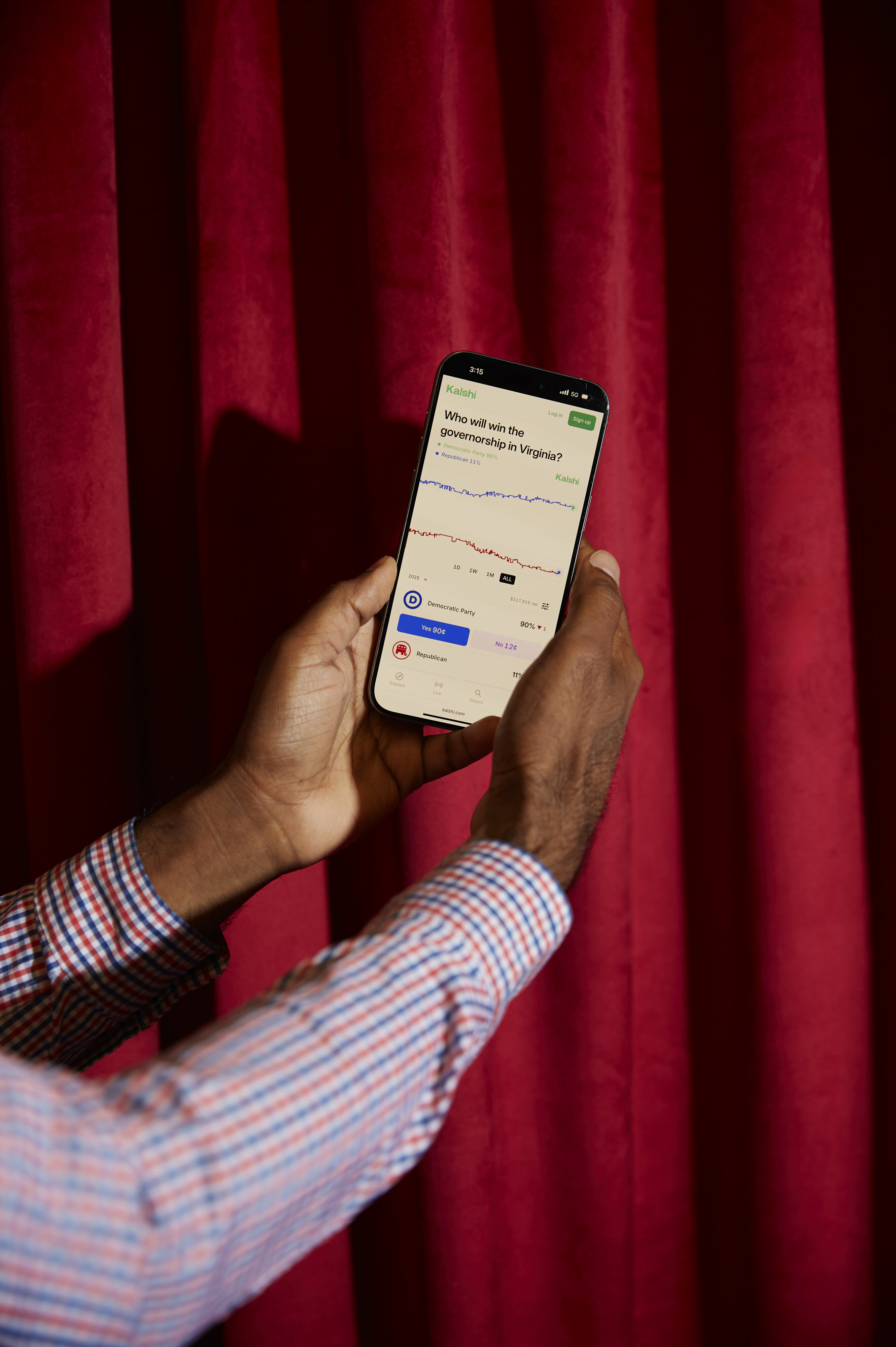

And that’s not all. At Kalshi, an online “prediction market,” you can wager on which party will control the House after the 2026 midterms, whether President Trump will take over the Panama Canal, or whether Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. will drop the federal ban on raw cow’s milk before the end of the year. The individual bets can be downright esoteric. Earlier this year, the forecasting platform Manifold was hosting wagers on the Supreme Court’s potential overturning of Humphrey’s Executor v. The United States, a 1935 case about the President’s power to remove the heads of independent federal agencies.

Small wonder, then, that the Washington area is home to a passionate political-betting community, a quirky confederation of guys who wear keep calm and don’t virtue signal T-shirts, devotees of Moneyball-meets-political-polling rock star/übernerd Nate Silver, and even one attorney from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

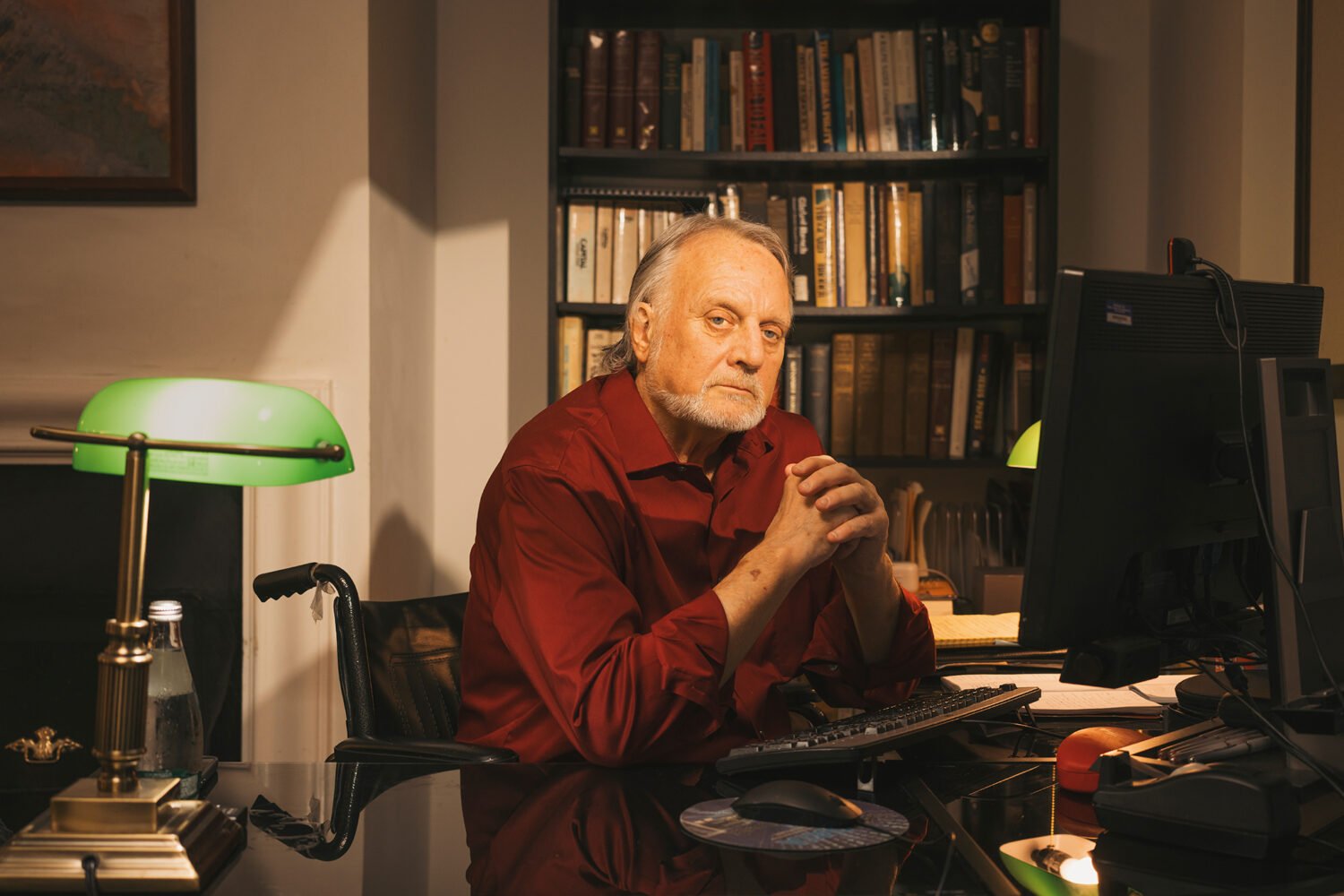

“Politics is the number-one sport for the national capital region,” says John Aristotle Phillips, whose political consulting firm, Aristotle, is the Pennsylvania Avenue–based incubator for PredictIt, another forecasting platform. “You’d be hard-pressed to find people who live inside the Beltway who don’t think their political acumen is superior to the average person. It’s logical they would put a little skin in the game.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find people who live inside the Beltway who don’t think their political acumen is superior to the average person. It’s logical they would put a little skin in the game.

Not everyone is enthused by the idea of turning one of the world’s longest-running democratic experiments into DraftKings. Federal regulators have long balked at political betting, and nascent operations such as Kalshi exist in a gray area that leaves them spending a lot of time fighting in court. On Capitol Hill, a trio of Democrats—Senator Jeff Merkley and Representative Andrea Salinas of Oregon and Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland—have introduced legislation that would ban this sort of wagering outright. “Election gambling is a bad bet for democracy,” Merkley says via email. “It reduces our democratic process to a horserace for the wealthy and powerful to bet on.”

Chougule believes otherwise. He heads a nonprofit, the Coalition for Political Forecasting, that advocates for loosening legal restrictions on political betting. In part, his goal is to protect and normalize what he considers to be a fun hobby. More than that, he wants to popularize a way of looking ahead that can rival traditional polling and punditry—two practices that, at least in the era of Donald Trump, have failed to see the future.

“We have a mechanism that can so efficiently and reliably identify people who are good at predictions, which is something our academic system does not do, our political system does not do,” Chougule says. “That, to me, is a pretty good argument.”

Getting Into the Game

Ask a sports-gambling enthusiast how they found their way into the activity and you’ll likely hear a story that begins with a big game, a favorite team, a group of friends starting a fantasy league—some sort of pathway from enjoying the action to wanting a piece of it.

Chougule’s road is different. It involves Donald Rumsfeld. Born in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, in 1986, Chougule says he was four when he developed his first strongly held political opinion. Iraq had invaded Kuwait, leading to Operation Desert Storm. A relative, Chougule recalls, explained that the US was the schoolyard protector stepping in to fight the bully.

That made sense to Chougule, who went off to Brown University a committed neoconservative. This was after 9/11, around the time the US invaded Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein’s regime. In college and after, Chougule helped foreign-policy figures research their memoirs. Eventually, he worked with Rumsfeld, the former Secretary of Defense who oversaw the Iraq invasion, on his 2012 memoir, Known and Unknown.

Chougule had backed that war, largely as an opportunity to promote democracy. But while working on Rumsfeld’s book, he was struck by how so much of the good that top officials thought would come from military intervention—such as Americans being “greeted as liberators” in the streets of Baghdad—never came close to happening. Meanwhile, some of the country’s top foreign-policy minds hadn’t anticipated the war’s catastrophic unintended consequences, such as the rise of the Islamic State.

“I came to view the Iraq experience,” Chougule says, “as fundamentally an error of forecasting and prediction.”

After graduating from Yale Law School, Chougule hopped into politics full-time. In 2016, he joined former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee’s presidential campaign as its policy coordinator. In Little Rock, Chougule discovered that domestic politics was as rife with predictive failures as foreign policy. When Huckabee started tanking in the polls, Chougule says, the campaign called a voluntary prayer meeting: “I’m thinking, ‘We don’t need a prayer session. We need a serious campaign-strategy session.’ ” And when a colleague circulated a draft opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, Chougule offered feedback saying the article was so ill-conceived that even submitting it would likely damage the campaign’s relationship with the newspaper.

As Chougule remembers it, a campaign higher-up chided him for “trash talk.” The Journal, he says, rejected the column. “How is it that we live in a society,” Chougule recalls thinking, “where making good predictions, offering your expertise, is not celebrated? That the better career move for me would have been to say, ‘That’s a great op-ed’?”

Around that time, Chougule discovered a place that valued good predictions: political-betting markets.

In 1916, when an estimated $294 million, adjusted for inflation, was wagered in New York’s Wall Street–adjacent political-gambling markets on the presidential election won by Woodrow Wilson—far more money than was spent on the actual campaigns.

Betting on politics goes back to the nation’s early days. In 1828, future President Martin Van Buren, then a New York politician, urged a friend to wager on the election. “Bet on Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois,” he advised. “Don’t forget to bet all you can.” The popularity of the practice is believed to have peaked in 1916, when an estimated $294 million (adjusted for inflation) was wagered in New York’s Wall Street–adjacent political-gambling markets on the presidential election won by Woodrow Wilson—far more money than was spent on the actual campaigns.

By the 1940s, however, political betting tapered off, disrupted by crackdowns on sports gambling, regulation of futures trading, and the rise of professional polling that was seen as a more scientific way of predicting election outcomes. In the 1990s, federal regulators began allowing University of Iowa students and faculty to make “trades” of as much as $500 on upcoming elections as part of an academic experiment, but otherwise put the kibosh on efforts to create political-gambling markets.

That changed in 2014, when the DC political-technology firm Aristotle came across a prediction-market platform being run out of a New Zealand university and decided to see if it could get American regulators’ approval. PredictIt was born. Chougule was drawn to the new platform: A poker player since college, he was intrigued by the way competitors think in terms of probabilities. Still working for Huckabee, he thought PredictIt users were undervaluing a long-shot candidate, Donald Trump. (Chougule worked briefly for the Trump campaign in the summer of 2016 but left, he says, amid instability in the operation’s policy shop.)

Chougule initially put a few hundred dollars into PredictIt. That grew to a few thousand. His knowledge of Republican politics led him to make good bets on GOP legislative struggles on Capitol Hill, such as attempts to shrink legal immigration. But that same understanding of how things usually worked also cost him: Chougule failed to accurately predict how Trump, after winning in 2016, would staff his administration.

Over time, Chougule became a better bettor. He learned to sense when to dip out of especially volatile markets, such as one around the career trajectory of then–FBI director James Comey. (Trump would fire Comey in the spring of 2017, only the second such firing in history.) Chougule’s work as a ghostwriter and an editor at two right-of-center magazines, the National Interest and the American Conservative, gave him an edge in so-called “mention markets,” in which people gambled on the frequency of particular phrases in politicians’ speeches.

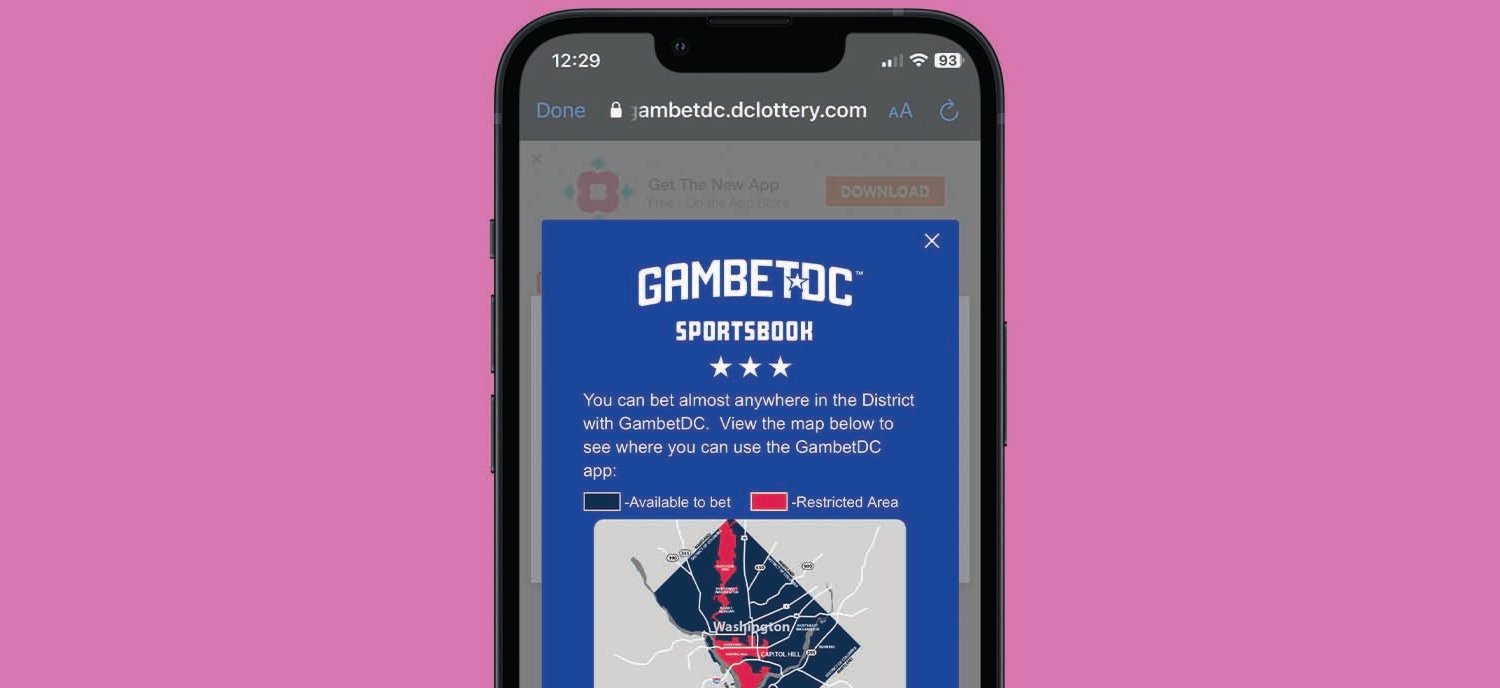

Chougule wasn’t alone in finding the markets compelling. Around that time, a pair of twentysomethings went into the famed YCombinator tech incubator with the idea of a prediction-markets platform for betting on everything from British soccer to Game of Thrones plot points. They called it Kalshi and won favor from investors for their willingness to go through the effort of trying to get regulators to officially approve it. Their gamble paid off: In 2020, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission approved Kalshi as what’s known as a “designated contract market.”

Betting on politics remained off-limits, so in 2023 Kalshi asked regulators to sign off on a market on whether Democrats or Republicans would control Congress. The CFTC balked, and PredictIt was caught up in the fallout, with regulators deciding it had overstepped its limited approval as an academic project focused on political events. The CFTC said some of PredictIt’s political “event contracts” were illegal in several states, and one person connected to the organization suspects that regulators were “annoyed” by markets such as one about whether Academy Award winners would mention Trump in their acceptance speeches.

As all of this was happening, Chougule concluded that political betting’s shaky legal status was downstream of its niche cultural status. The people who make the rules in Washington looked down on the practice and ended up writing rules to codify their disdain. To change that, he reasoned, he would have to do for political wagering what leagues, broadcasters, and paid celebrity endorsers have done for sports wagering: make it appeal to normies.

Building a Bigger Tent

On a Wednesday night in February, the DC Forecasting and Predictions Markets meetup network gathers upstairs at the Ugly Mug, a rough-around-the-edges bar on the border of Capitol Hill. Luke, a twentysomething, and River, a gray-haired engineer with a law degree, are chatting about Humphrey’s Executor, the 1935 Supreme Court case limiting presidential power over some independent agencies.

Kayla Gamin stands nearby. A federal attorney, she also works part-time for the Forecasting Research Institute, an organization that trains people in the art of making predictions about “high-stakes” issues. Gamin has set up a wager on the platform Manifold—which uses play money called “Mana”—on whether Humphrey’s might be struck down amid President Trump’s push to consolidate executive power. But there’s a problem: Her bet isn’t attracting enough informed predictions to make its forecast worthwhile.

“Lawyers aren’t joining her market,” Luke says.

“Well, I’m certainly going to read the [90-year-old Supreme Court] opinion before I bet on that,” replies River, who weeks later will put down 250 Mana in favor of the court overturning Humphrey’s.

Organized by Chougule and DC-area tech product manager David Glidden, this gathering is part of Chougule’s effort to create a bigger political-betting community. Current enthusiasts, he explains, tend to be introverted and accustomed to connecting online. Bringing them together in real life, Chougule says, can create stronger bonds and help them feel strength in numbers. Luke, the twentysomething, says he’s been to similar events in the Bay Area. This one feels different. “Everybody here is, like, a lawyer or [working] at a nonprofit,” he says. “It’s more humanitarian.” Glidden is wearing a USAID hat—until recently, his wife worked at the DOGE-gutted agency—and says it’s nice to be around people who share his way of seeing the world. “We feel a little bit at odds with a normal person,” he says.

Chougule’s meetup network has chapters in Berlin, Dallas, and New York as well as planned expansions to San Francisco, London, and Prague. His nonprofit—which began as a research project paid for by a fund promoting so-called effective altruism—is meant to bring together sympathetic academics and others. Then there’s his podcast, Star Spangled Gamblers, which was created in 2018 by Alex Keeney, a former congressional staffer turned TV writer.

Early on, Keeney—known as “Keendawg” in online circles—hosted the podcast with a bro-tastic edginess familiar to anyone who has consumed sports-gambling content. Fellow political-betting fans were referred to as “degens,” short for degenerates—one early segment on the falling stock of certain political figures was called “Who Needs a Beer?” When Keeney left for a job as an audio producer at Politico in 2022, Chougule took over hosting, and he has since put out regular episodes from his home study in Arlington, covering everything from whether Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s alleged “weirdness” should factor into predictions about his political future to timing congressional debt-ceiling-negotiation bets. “A lot of the day-to-day churn” of the prediction-market world, Chougule says, “is young men doing what they do in internet forums.”

Chougule is making a case for the hobby’s predictive power—that political-gambling sharps are at least as good, and sometimes better, at peering into the crystal ball as the Nate Silvers of the world.

Listen to a few episodes, however, and it’s clear that Chougule isn’t simply trying to help fellow degens calculate the odds of DeSantis 2028 being sunk by the candidate’s habit of flicking out his tongue while speaking. Chougule is making a case for the hobby’s predictive power—that political-gambling sharps are at least as good, and sometimes better, at peering into the crystal ball as the Nate Silvers of the world.

In late April, Chougule’s guest on the podcast was a political bettor—or “trader,” as they like to call themselves—nicknamed Blitz. His claim to fame? Correctly forecasting the outcome of the presidential election, including every state, in 2020 and 2024. Blitz’s techniques include underweighting the candidates people tell pollsters they’re voting for (“People lie about everything,” he says) and scrutinizing issue-based polling questions. For example, Blitz argues, responding in the affirmative to “Are you concerned about the future of democracy in the US?” was wrongly assumed to mean that a potential voter had anti-Trump leanings.

Prediction markets gave Trump slightly better odds of winning in 2024 than polling did—but overall, their track record is mixed. Researchers have found that markets tend to make better forecasts when outcomes are black-and-white and tied to a regular cadence: whether the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at scheduled meetings, for example, or whether the federal government will shut down when the current budget expires. They’re less good at predicting messier events, particularly those in which a great deal of emotion is involved. The markets whiffed on Brexit and also gave American cardinal Robert Prevost 1-in-100 odds of becoming pope, a failure Chougule attributes in part to the papal conclave’s extraordinary secrecy.

Those shortcomings, Chougule admits, are another reason he wants to mainstream political betting. The 2015 book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction—something of a bible of the field—argues that while some people are, by nature or training, especially good at forecasting, even they can benefit from working together. More bettors making more wagers should mean better predictions, and better predictions could mean fewer mistakes. “Sometimes,” Chougule says, “the wisdom of the crowd does indeed tell you something.”

A Bad Bet?

A few weeks after meeting up with Chougule at Nanny O’Brien’s, I decide to test my own forecasting powers. After depositing a small bit of money into Kalshi, one particular mention market catches my eye: What will White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt say in that afternoon’s press briefing?

I buy three contracts, for 50 cents each, in favor of Leavitt dropping the name of a Maryland resident deported to El Salvador despite a Supreme Court ruling on the matter. Five minutes later, score! “The media outrage over [the] deportation of [Kilmar] Abrego Garcia,” Leavitt says, “has been nothing short of despicable.” My three contracts are now worth $3. Minus transaction fees, I’m up $1.41. (I subsequently donate my winnings to the Society of Professional Journalists.)

The country, at that moment, arguably stood at the edge of a constitutional crisis. Moreover, a fellow human being’s life was at stake. But to me, with less than two bucks on the line, it didn’t feel like what Kalshi calls “trading on the outcome of future events.” It felt akin to betting on Terps–Gators, entirely like a game.

That’s part of what troubles political-betting opponents like Merkley, who warns against “turning elections into a rigged gambling casino.” That’s not the only risk. As part of their case against Kalshi, federal regulators argued last year that political-betting markets are likely to be plagued by market-moving misinformation and collusion—in the two weeks before the 2012 election, for example, a single anonymous trader bet millions on Mitt Romney in what appeared to be an effort to make the presidential race look closer than it was, perhaps to boost the Romney campaign’s fundraising or morale. Such efforts could damage election integrity, or at least harm the public’s already-waning faith in the system.

Election gambling is a bad bet for democracy. It reduces our democratic process to a horserace for the wealthy and powerful to bet on.

Political betting also could lead people to vote not for the candidates they genuinely prefer but for the ones who will produce a payout. Athletes have been known to perform poorly and even lose games on purpose in order to collect on bets against themselves and their teams. Would unscrupulous politicians do the same by sabotaging themselves or their parties? Congressman Raskin worries that gambling on elections will further increase the influence of unaccountable money in politics—deep-pocketed bettors would have reason to pour cash into campaigns—while making harassment and violence against election workers and politicians more likely. (In sports, legalized betting has resulted in much more public invective directed against athletes.)

Merkley even frets about “insider trading.” In the UK, where political betting is legal and ingrained in the culture, a former lawmaker was among 15 people charged in April with cheating when placing bets on the surprise timing of Britain’s 2024 general election, about which they allegedly had inside information. (Kalshi has restrictions aimed at shutting down insider trading, including banning those who have the ability to influence the outcome being bet on.)

Chougule is sympathetic to concerns that such wagering may weaken public faith in American democracy. He left the GOP—and much of his political career—partly because of Trump’s insistence that he won the 2020 election and the resulting attacks of January 6. Chougule also says that more research on other potential drawbacks is needed.

But otherwise, he dismisses many of Merkley and company’s warnings. Corporations and the ultra-rich using betting to put their thumbs on the electoral scale? Our political system already is awash in cash, he says. Insider trading? Chougule admits that incidents like the UK scandal could “erode confidence” in the democratic process. But in general, he says, “I love that insiders are trading”—because if the goal is to surface the most accurate prediction, then “the more insider trading you have in these markets, the more accurate, theoretically, the price signal will be.”

Ultimately, Chougule argues, the UK shows that political gambling and representative government can coexist. “They have total free-for-all betting,” he says, “and I don’t think anyone would argue the UK is not a legitimate democracy.” More provocatively, he argues that prediction markets could improve our politics, offering a way forward for people who are, like him, “tired of the tribalism, of the back-and-forth shouting.” If more Americans start putting their money where their mouths are, he says, they might be less prone to inflamed political passions and partisanship. “You start to think more about not what should happen,” Chougule says, “but what will happen.”

For now, the legal landscape for US prediction markets is uncertain—but things appear to be trending in their favor. Trump’s initial political rise and subsequent comeback gave them a double shot of publicity and legitimacy, and his administration has been friendlier than President Biden’s. This winter, Kalshi named Trump’s son Don Jr. as a strategic adviser. “On election night at Mar-a-Lago, while biased outlets called the race a coin toss, my family and close friends used the prediction market Kalshi to know we won hours ahead of the fake news media,” Trump Jr. posted on X. “I immediately knew I had to contribute to their mission.” The next month, President Trump nominated a Kalshi board member to head the federal agency with regulatory oversight of prediction markets. In May, federal regulators pulled out of a lawsuit that aimed to prevent Kalshi from offering political markets.

For Chougule, this creates something of a dilemma. “I think [Trump’s] been very destructive in all kinds of ways, and I’ve never voted for him,” he says. “But I have to grudgingly concede that on this issue, we’re doing pretty well.” Will that continue? On Kalshi, there’s—surprisingly—no active wagering on the future of prediction markets.

t’s a springtime Thursday night at Nanny O’Brien’s Irish Pub in Northwest DC, and up on the TVs, the University of Maryland men’s basketball team is struggling against the University of Florida. The bar is stuffed with revelers eating chicken wings and drinking beer. Given that Americans will wager an estimated $3.1 billion on college basketball’s championship tournament this year, it’s a fair bet that at least some of them are fretting about what they have riding on the game.

Pratik Chougule is thinking about wagers, too—just not on sports. “I don’t understand how we can have this quasi-national religion in which everyone in their 9-to-5 jobs, when they should be working, is checking their March Madness bracket,” he says over the din. “Why is that okay, but a betting market on something as important as a piece of legislation or an election outcome, that is the thing we really police?”

A 39-year-old lawyer in Northern Virginia, Chougule is one of the country’s most outspoken advocates for political betting—a relatively small, definitely growing, questionably legal pastime that is, well, exactly what it sounds like. Just as sports fans wager on the outcome of tennis matches and Washington Commanders games, people like Chougule gamble on who will win electoral races.

And that’s not all. At Kalshi, an online “prediction market,” you can wager on which party will control the House after the 2026 midterms, whether President Trump will take over the Panama Canal, or whether Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. will drop the federal ban on raw cow’s milk before the end of the year. The individual bets can be downright esoteric. Earlier this year, the forecasting platform Manifold was hosting wagers on the Supreme Court’s potential overturning of Humphrey’s Executor v. The United States, a 1935 case about the President’s power to remove the heads of independent federal agencies.

Small wonder, then, that the Washington area is home to a passionate political-betting community, a quirky confederation of guys who wear keep calm and don’t virtue signal T-shirts, devotees of Moneyball-meets-political-polling rock star/übernerd Nate Silver, and even one attorney from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

“Politics is the number-one sport for the national capital region,” says John Aristotle Phillips, whose political consulting firm, Aristotle, is the Pennsylvania Avenue–based incubator for PredictIt, another forecasting platform. “You’d be hard-pressed to find people who live inside the Beltway who don’t think their political acumen is superior to the average person. It’s logical they would put a little skin in the game.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find people who live inside the Beltway who don’t think their political acumen is superior to the average person. It’s logical they would put a little skin in the game.

Not everyone is enthused by the idea of turning one of the world’s longest-running democratic experiments into DraftKings. Federal regulators have long balked at political betting, and nascent operations such as Kalshi exist in a gray area that leaves them spending a lot of time fighting in court. On Capitol Hill, a trio of Democrats—Senator Jeff Merkley and Representative Andrea Salinas of Oregon and Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland—have introduced legislation that would ban this sort of wagering outright. “Election gambling is a bad bet for democracy,” Merkley says via email. “It reduces our democratic process to a horserace for the wealthy and powerful to bet on.”

Chougule believes otherwise. He heads a nonprofit, the Coalition for Political Forecasting, that advocates for loosening legal restrictions on political betting. In part, his goal is to protect and normalize what he considers to be a fun hobby. More than that, he wants to popularize a way of looking ahead that can rival traditional polling and punditry—two practices that, at least in the era of Donald Trump, have failed to see the future.

“We have a mechanism that can so efficiently and reliably identify people who are good at predictions, which is something our academic system does not do, our political system does not do,” Chougule says. “That, to me, is a pretty good argument.”

Getting Into the Game

Ask a sports-gambling enthusiast how they found their way into the activity and you’ll likely hear a story that begins with a big game, a favorite team, a group of friends starting a fantasy league—some sort of pathway from enjoying the action to wanting a piece of it.

Chougule’s road is different. It involves Donald Rumsfeld. Born in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, in 1986, Chougule says he was four when he developed his first strongly held political opinion. Iraq had invaded Kuwait, leading to Operation Desert Storm. A relative, Chougule recalls, explained that the US was the schoolyard protector stepping in to fight the bully.

That made sense to Chougule, who went off to Brown University a committed neoconservative. This was after 9/11, around the time the US invaded Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein’s regime. In college and after, Chougule helped foreign-policy figures research their memoirs. Eventually, he worked with Rumsfeld, the former Secretary of Defense who oversaw the Iraq invasion, on his 2012 memoir, Known and Unknown.

Chougule had backed that war, largely as an opportunity to promote democracy. But while working on Rumsfeld’s book, he was struck by how so much of the good that top officials thought would come from military intervention—such as Americans being “greeted as liberators” in the streets of Baghdad—never came close to happening. Meanwhile, some of the country’s top foreign-policy minds hadn’t anticipated the war’s catastrophic unintended consequences, such as the rise of the Islamic State.

“I came to view the Iraq experience,” Chougule says, “as fundamentally an error of forecasting and prediction.”

After graduating from Yale Law School, Chougule hopped into politics full-time. In 2016, he joined former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee’s presidential campaign as its policy coordinator. In Little Rock, Chougule discovered that domestic politics was as rife with predictive failures as foreign policy. When Huckabee started tanking in the polls, Chougule says, the campaign called a voluntary prayer meeting: “I’m thinking, ‘We don’t need a prayer session. We need a serious campaign-strategy session.’ ” And when a colleague circulated a draft opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, Chougule offered feedback saying the article was so ill-conceived that even submitting it would likely damage the campaign’s relationship with the newspaper.

As Chougule remembers it, a campaign higher-up chided him for “trash talk.” The Journal, he says, rejected the column. “How is it that we live in a society,” Chougule recalls thinking, “where making good predictions, offering your expertise, is not celebrated? That the better career move for me would have been to say, ‘That’s a great op-ed’?”

Around that time, Chougule discovered a place that valued good predictions: political-betting markets.

In 1916, when an estimated $294 million, adjusted for inflation, was wagered in New York’s Wall Street–adjacent political-gambling markets on the presidential election won by Woodrow Wilson—far more money than was spent on the actual campaigns.

Betting on politics goes back to the nation’s early days. In 1828, future President Martin Van Buren, then a New York politician, urged a friend to wager on the election. “Bet on Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois,” he advised. “Don’t forget to bet all you can.” The popularity of the practice is believed to have peaked in 1916, when an estimated $294 million (adjusted for inflation) was wagered in New York’s Wall Street–adjacent political-gambling markets on the presidential election won by Woodrow Wilson—far more money than was spent on the actual campaigns.

By the 1940s, however, political betting tapered off, disrupted by crackdowns on sports gambling, regulation of futures trading, and the rise of professional polling that was seen as a more scientific way of predicting election outcomes. In the 1990s, federal regulators began allowing University of Iowa students and faculty to make “trades” of as much as $500 on upcoming elections as part of an academic experiment, but otherwise put the kibosh on efforts to create political-gambling markets.

That changed in 2014, when the DC political-technology firm Aristotle came across a prediction-market platform being run out of a New Zealand university and decided to see if it could get American regulators’ approval. PredictIt was born. Chougule was drawn to the new platform: A poker player since college, he was intrigued by the way competitors think in terms of probabilities. Still working for Huckabee, he thought PredictIt users were undervaluing a long-shot candidate, Donald Trump. (Chougule worked briefly for the Trump campaign in the summer of 2016 but left, he says, amid instability in the operation’s policy shop.)

Chougule initially put a few hundred dollars into PredictIt. That grew to a few thousand. His knowledge of Republican politics led him to make good bets on GOP legislative struggles on Capitol Hill, such as attempts to shrink legal immigration. But that same understanding of how things usually worked also cost him: Chougule failed to accurately predict how Trump, after winning in 2016, would staff his administration.

Over time, Chougule became a better bettor. He learned to sense when to dip out of especially volatile markets, such as one around the career trajectory of then–FBI director James Comey. (Trump would fire Comey in the spring of 2017, only the second such firing in history.) Chougule’s work as a ghostwriter and an editor at two right-of-center magazines, the National Interest and the American Conservative, gave him an edge in so-called “mention markets,” in which people gambled on the frequency of particular phrases in politicians’ speeches.

Chougule wasn’t alone in finding the markets compelling. Around that time, a pair of twentysomethings went into the famed YCombinator tech incubator with the idea of a prediction-markets platform for betting on everything from British soccer to Game of Thrones plot points. They called it Kalshi and won favor from investors for their willingness to go through the effort of trying to get regulators to officially approve it. Their gamble paid off: In 2020, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission approved Kalshi as what’s known as a “designated contract market.”

Betting on politics remained off-limits, so in 2023 Kalshi asked regulators to sign off on a market on whether Democrats or Republicans would control Congress. The CFTC balked, and PredictIt was caught up in the fallout, with regulators deciding it had overstepped its limited approval as an academic project focused on political events. The CFTC said some of PredictIt’s political “event contracts” were illegal in several states, and one person connected to the organization suspects that regulators were “annoyed” by markets such as one about whether Academy Award winners would mention Trump in their acceptance speeches.

As all of this was happening, Chougule concluded that political betting’s shaky legal status was downstream of its niche cultural status. The people who make the rules in Washington looked down on the practice and ended up writing rules to codify their disdain. To change that, he reasoned, he would have to do for political wagering what leagues, broadcasters, and paid celebrity endorsers have done for sports wagering: make it appeal to normies.

Building a Bigger Tent

On a Wednesday night in February, the DC Forecasting and Predictions Markets meetup network gathers upstairs at the Ugly Mug, a rough-around-the-edges bar on the border of Capitol Hill. Luke, a twentysomething, and River, a gray-haired engineer with a law degree, are chatting about Humphrey’s Executor, the 1935 Supreme Court case limiting presidential power over some independent agencies.

Kayla Gamin stands nearby. A federal attorney, she also works part-time for the Forecasting Research Institute, an organization that trains people in the art of making predictions about “high-stakes” issues. Gamin has set up a wager on the platform Manifold—which uses play money called “Mana”—on whether Humphrey’s might be struck down amid President Trump’s push to consolidate executive power. But there’s a problem: Her bet isn’t attracting enough informed predictions to make its forecast worthwhile.

“Lawyers aren’t joining her market,” Luke says.

“Well, I’m certainly going to read the [90-year-old Supreme Court] opinion before I bet on that,” replies River, who weeks later will put down 250 Mana in favor of the court overturning Humphrey’s.

Organized by Chougule and DC-area tech product manager David Glidden, this gathering is part of Chougule’s effort to create a bigger political-betting community. Current enthusiasts, he explains, tend to be introverted and accustomed to connecting online. Bringing them together in real life, Chougule says, can create stronger bonds and help them feel strength in numbers. Luke, the twentysomething, says he’s been to similar events in the Bay Area. This one feels different. “Everybody here is, like, a lawyer or [working] at a nonprofit,” he says. “It’s more humanitarian.” Glidden is wearing a USAID hat—until recently, his wife worked at the DOGE-gutted agency—and says it’s nice to be around people who share his way of seeing the world. “We feel a little bit at odds with a normal person,” he says.

Chougule’s meetup network has chapters in Berlin, Dallas, and New York as well as planned expansions to San Francisco, London, and Prague. His nonprofit—which began as a research project paid for by a fund promoting so-called effective altruism—is meant to bring together sympathetic academics and others. Then there’s his podcast, Star Spangled Gamblers, which was created in 2018 by Alex Keeney, a former congressional staffer turned TV writer.

Early on, Keeney—known as “Keendawg” in online circles—hosted the podcast with a bro-tastic edginess familiar to anyone who has consumed sports-gambling content. Fellow political-betting fans were referred to as “degens,” short for degenerates—one early segment on the falling stock of certain political figures was called “Who Needs a Beer?” When Keeney left for a job as an audio producer at Politico in 2022, Chougule took over hosting, and he has since put out regular episodes from his home study in Arlington, covering everything from whether Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s alleged “weirdness” should factor into predictions about his political future to timing congressional debt-ceiling-negotiation bets. “A lot of the day-to-day churn” of the prediction-market world, Chougule says, “is young men doing what they do in internet forums.”

Chougule is making a case for the hobby’s predictive power—that political-gambling sharps are at least as good, and sometimes better, at peering into the crystal ball as the Nate Silvers of the world.

Listen to a few episodes, however, and it’s clear that Chougule isn’t simply trying to help fellow degens calculate the odds of DeSantis 2028 being sunk by the candidate’s habit of flicking out his tongue while speaking. Chougule is making a case for the hobby’s predictive power—that political-gambling sharps are at least as good, and sometimes better, at peering into the crystal ball as the Nate Silvers of the world.

In late April, Chougule’s guest on the podcast was a political bettor—or “trader,” as they like to call themselves—nicknamed Blitz. His claim to fame? Correctly forecasting the outcome of the presidential election, including every state, in 2020 and 2024. Blitz’s techniques include underweighting the candidates people tell pollsters they’re voting for (“People lie about everything,” he says) and scrutinizing issue-based polling questions. For example, Blitz argues, responding in the affirmative to “Are you concerned about the future of democracy in the US?” was wrongly assumed to mean that a potential voter had anti-Trump leanings.

Prediction markets gave Trump slightly better odds of winning in 2024 than polling did—but overall, their track record is mixed. Researchers have found that markets tend to make better forecasts when outcomes are black-and-white and tied to a regular cadence: whether the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at scheduled meetings, for example, or whether the federal government will shut down when the current budget expires. They’re less good at predicting messier events, particularly those in which a great deal of emotion is involved. The markets whiffed on Brexit and also gave American cardinal Robert Prevost 1-in-100 odds of becoming pope, a failure Chougule attributes in part to the papal conclave’s extraordinary secrecy.

Those shortcomings, Chougule admits, are another reason he wants to mainstream political betting. The 2015 book Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction—something of a bible of the field—argues that while some people are, by nature or training, especially good at forecasting, even they can benefit from working together. More bettors making more wagers should mean better predictions, and better predictions could mean fewer mistakes. “Sometimes,” Chougule says, “the wisdom of the crowd does indeed tell you something.”

A Bad Bet?

A few weeks after meeting up with Chougule at Nanny O’Brien’s, I decide to test my own forecasting powers. After depositing a small bit of money into Kalshi, one particular mention market catches my eye: What will White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt say in that afternoon’s press briefing?

I buy three contracts, for 50 cents each, in favor of Leavitt dropping the name of a Maryland resident deported to El Salvador despite a Supreme Court ruling on the matter. Five minutes later, score! “The media outrage over [the] deportation of [Kilmar] Abrego Garcia,” Leavitt says, “has been nothing short of despicable.” My three contracts are now worth $3. Minus transaction fees, I’m up $1.41. (I subsequently donate my winnings to the Society of Professional Journalists.)

The country, at that moment, arguably stood at the edge of a constitutional crisis. Moreover, a fellow human being’s life was at stake. But to me, with less than two bucks on the line, it didn’t feel like what Kalshi calls “trading on the outcome of future events.” It felt akin to betting on Terps–Gators, entirely like a game.

That’s part of what troubles political-betting opponents like Merkley, who warns against “turning elections into a rigged gambling casino.” That’s not the only risk. As part of their case against Kalshi, federal regulators argued last year that political-betting markets are likely to be plagued by market-moving misinformation and collusion—in the two weeks before the 2012 election, for example, a single anonymous trader bet millions on Mitt Romney in what appeared to be an effort to make the presidential race look closer than it was, perhaps to boost the Romney campaign’s fundraising or morale. Such efforts could damage election integrity, or at least harm the public’s already-waning faith in the system.

Election gambling is a bad bet for democracy. It reduces our democratic process to a horserace for the wealthy and powerful to bet on.

Political betting also could lead people to vote not for the candidates they genuinely prefer but for the ones who will produce a payout. Athletes have been known to perform poorly and even lose games on purpose in order to collect on bets against themselves and their teams. Would unscrupulous politicians do the same by sabotaging themselves or their parties? Congressman Raskin worries that gambling on elections will further increase the influence of unaccountable money in politics—deep-pocketed bettors would have reason to pour cash into campaigns—while making harassment and violence against election workers and politicians more likely. (In sports, legalized betting has resulted in much more public invective directed against athletes.)

Merkley even frets about “insider trading.” In the UK, where political betting is legal and ingrained in the culture, a former lawmaker was among 15 people charged in April with cheating when placing bets on the surprise timing of Britain’s 2024 general election, about which they allegedly had inside information. (Kalshi has restrictions aimed at shutting down insider trading, including banning those who have the ability to influence the outcome being bet on.)

Chougule is sympathetic to concerns that such wagering may weaken public faith in American democracy. He left the GOP—and much of his political career—partly because of Trump’s insistence that he won the 2020 election and the resulting attacks of January 6. Chougule also says that more research on other potential drawbacks is needed.

But otherwise, he dismisses many of Merkley and company’s warnings. Corporations and the ultra-rich using betting to put their thumbs on the electoral scale? Our political system already is awash in cash, he says. Insider trading? Chougule admits that incidents like the UK scandal could “erode confidence” in the democratic process. But in general, he says, “I love that insiders are trading”—because if the goal is to surface the most accurate prediction, then “the more insider trading you have in these markets, the more accurate, theoretically, the price signal will be.”

Ultimately, Chougule argues, the UK shows that political gambling and representative government can coexist. “They have total free-for-all betting,” he says, “and I don’t think anyone would argue the UK is not a legitimate democracy.” More provocatively, he argues that prediction markets could improve our politics, offering a way forward for people who are, like him, “tired of the tribalism, of the back-and-forth shouting.” If more Americans start putting their money where their mouths are, he says, they might be less prone to inflamed political passions and partisanship. “You start to think more about not what should happen,” Chougule says, “but what will happen.”

For now, the legal landscape for US prediction markets is uncertain—but things appear to be trending in their favor. Trump’s initial political rise and subsequent comeback gave them a double shot of publicity and legitimacy, and his administration has been friendlier than President Biden’s. This winter, Kalshi named Trump’s son Don Jr. as a strategic adviser. “On election night at Mar-a-Lago, while biased outlets called the race a coin toss, my family and close friends used the prediction market Kalshi to know we won hours ahead of the fake news media,” Trump Jr. posted on X. “I immediately knew I had to contribute to their mission.” The next month, President Trump nominated a Kalshi board member to head the federal agency with regulatory oversight of prediction markets. In May, federal regulators pulled out of a lawsuit that aimed to prevent Kalshi from offering political markets.

For Chougule, this creates something of a dilemma. “I think [Trump’s] been very destructive in all kinds of ways, and I’ve never voted for him,” he says. “But I have to grudgingly concede that on this issue, we’re doing pretty well.” Will that continue? On Kalshi, there’s—surprisingly—no active wagering on the future of prediction markets.

Photograph of dice by Tim Grist Photography/Getty Images.

This article appears in the July 2025 issue of Washingtonian.