Contents

- uring the War of 1812, British troops famously torched the US Capitol, burning down the still-new home of the fledgling country’s legislative body. Also going up in flames? Roughly 3,000 books, largely about law, that made up the Library of Congress’s core collection.

- “America’s Birth Certificate”

- Sounds of Earth

- Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an

- Frankenstein

- The Gutenberg Bible

- Relics of a Tragedy

- Proposal for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

- Leaves of Grass

- “American Gothic”

- Stradivarius Instruments

- Strange Treasures

uring the War of 1812, British troops famously torched the US Capitol, burning down the still-new home of the fledgling country’s legislative body. Also going up in flames? Roughly 3,000 books, largely about law, that made up the Library of Congress’s core collection.

Within a month, former President and noted bibliophile Thomas Jefferson offered his personal library as a replacement. His offer was warmly received by many in the House and Senate, but not by all. Massachusetts representative Cyrus King, an opposition Federalist, argued that Jefferson’s diverse holdings—which included works in Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, and Old English, as well as a translation of the Qur’an—would foster his “infidel philosophy” while being “in languages which many cannot read, and most ought not.”

The bill narrowly passed, along party lines, and Congress paid almost $24,000 for Jefferson’s 6,487 books. On May 8, 1815, as a final wagonload of books left Monticello, Jefferson wrote to Samuel Harrison Smith, who had helped facilitate the sale, that “an interesting treasure is added to . . . the depository of unquestionably the choicest collection of books in the U.S. and I hope it will not be without some general effect on the literature of our country.”

Jefferson eventually got his wish. Today, the Library of Congress is a national jewel. Its main building on Capitol Hill, opened in 1897 and later named for the Founding Father, is home to a domed Main Reading Room that endures as one of Washington’s most elegant spaces. Within the library’s collection of more than 178 million items, the world’s largest, are a number of incredible treasures—and across the following pages, we’ve highlighted some of our favorites.

More incredible still? Most of what the institution has to offer is accessible with a simple library card.

In many ways, the modern library is the brainchild of former Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Spofford, a visionary who lobbied Abraham Lincoln for the job and then stayed on through nine (!) Presidents. Spofford led construction of the Thomas Jefferson Building and a major expansion of the collection, working toward his broader goal of establishing a national library. He succeeded yet never lost sight of the institution’s original mission to serve legislators: For decades, the Jefferson Building and the Capitol were connected by an underground tunnel equipped with an electric book trolley and pneumatic message tubes. Lawmakers (or really, their staffers and pages) could send book requests to librarians via the tubes, and librarians could send books back via the trolley.

In the early 2000s, the book tunnel was demolished to make room for the underground Capitol Visitor Center. A separate, pedestrian-friendly tunnel now links the two buildings, where librarians can still be spotted wheeling book carts from time to time. That’s hardly the only way the library has evolved. Its physical collection is now housed in three Capitol Hill buildings and other facilities in Maryland and Virginia; its digital collection, begun in 1994, contains more than 900 million files; its collections of sounds, music, prints, moving images, and photographs date back more than 100 years and continue to grow alongside audiovisual media and communication.

In fact, the library adds more than 10,000 items each and every working day. Every year, it adds 25 recordings of “cultural, historical or aesthetic significance” to its National Recording Registry, through a nomination process that’s open to the public. A similar process annually expands the National Film Registry, which contains both Citizen Kane and Shrek. As former Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden puts it, the institution is a perpetual “work in progress,” much like the country it serves.

Speaking to Washingtonian this spring—before President Trump fired her in early May—Hayden said the library had recently acquired composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim’s papers, a victory in its friendly rivalry with the New York Public Library over arts and cultural acquisitions. Even among the library’s standing collections, new discoveries are sometimes made. To wit: A couple of years ago, using spectral-imaging processes, it was revealed that, in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson had originally written “our fellow subjects” before changing the phrase to “our fellow citizens.”

“What we like to highlight—and exhibit—is the process of creativity,” Hayden said. “Anybody can physically go into the building to sit down in a reading room. We have 16 spread out between the three buildings. You have the manuscripts; the bulk of that historic material; print and photographs; and the music, theater, and performing-arts divisions. You see really cool stuff.”

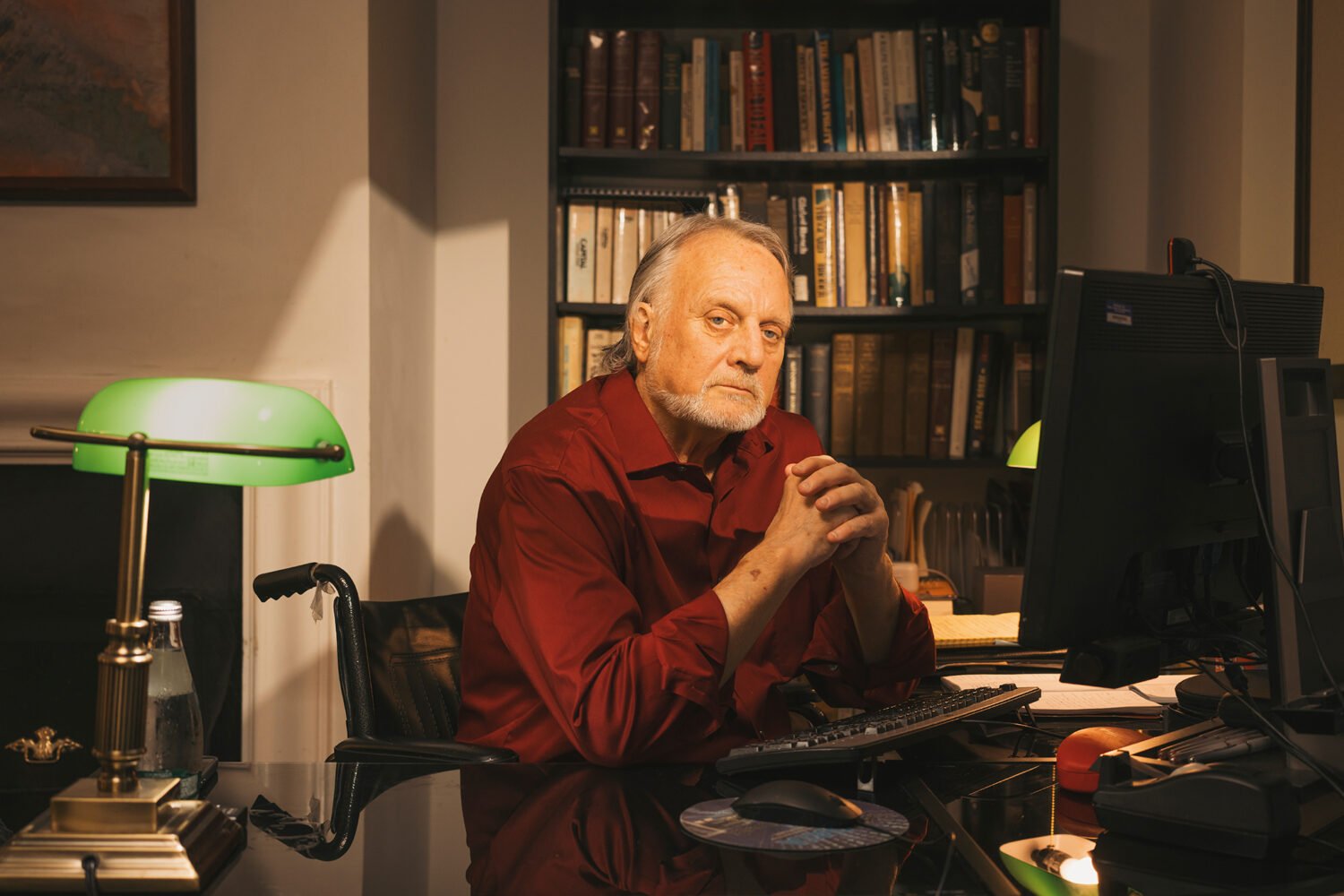

Visit the library at the right time, she added, and you may even catch someone you recognize in the throes of said creative process. “With all these wonderful resources, people who write books are often here,” she said, noting that acclaimed filmmaker Ken Burns “sits here for hours and hours doing research for every documentary that he does. He never fails to mention the library in his credits.”

Hayden smiled. “But if you are just a curious person, we want you to come, too.”

Back to Top

“America’s Birth Certificate”

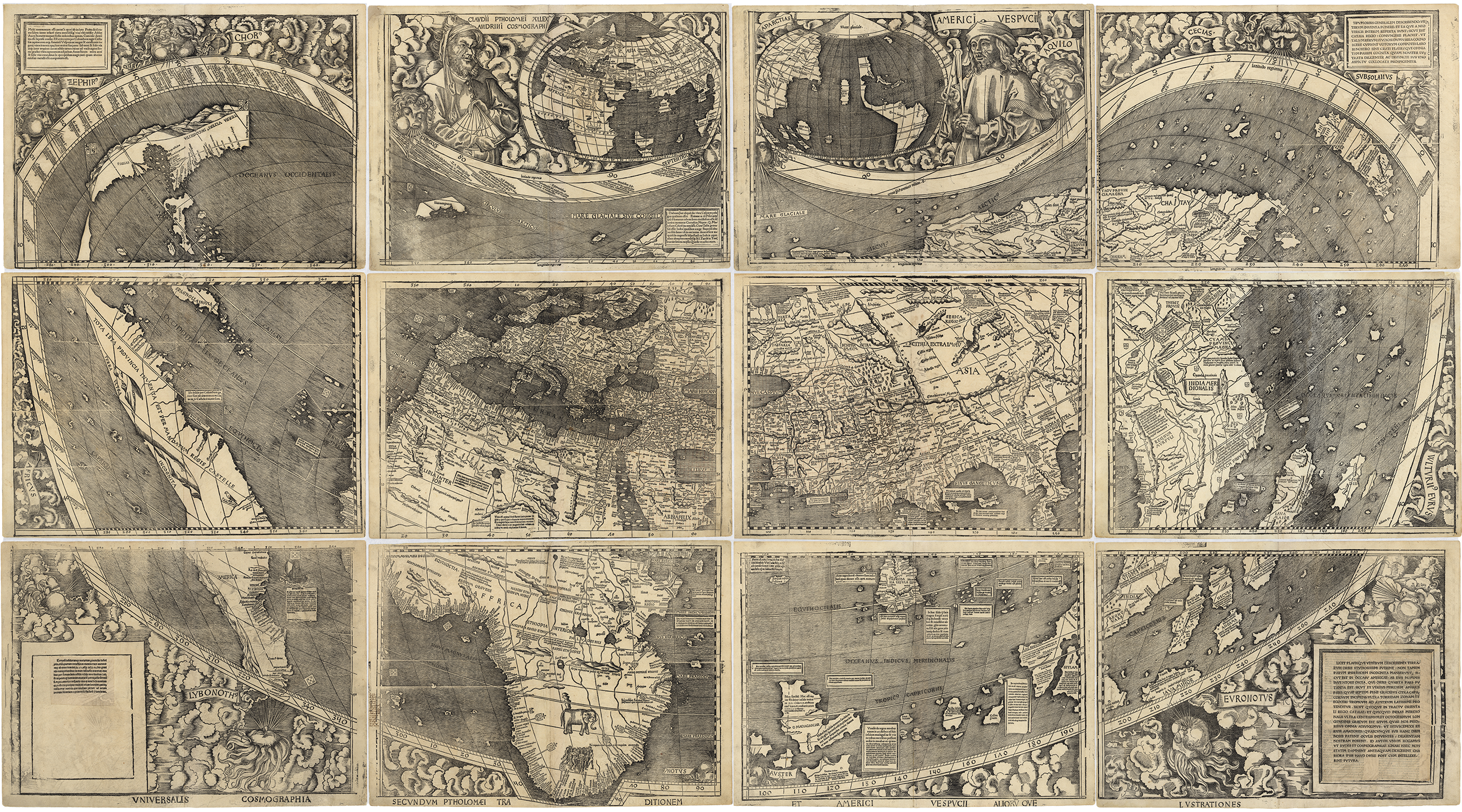

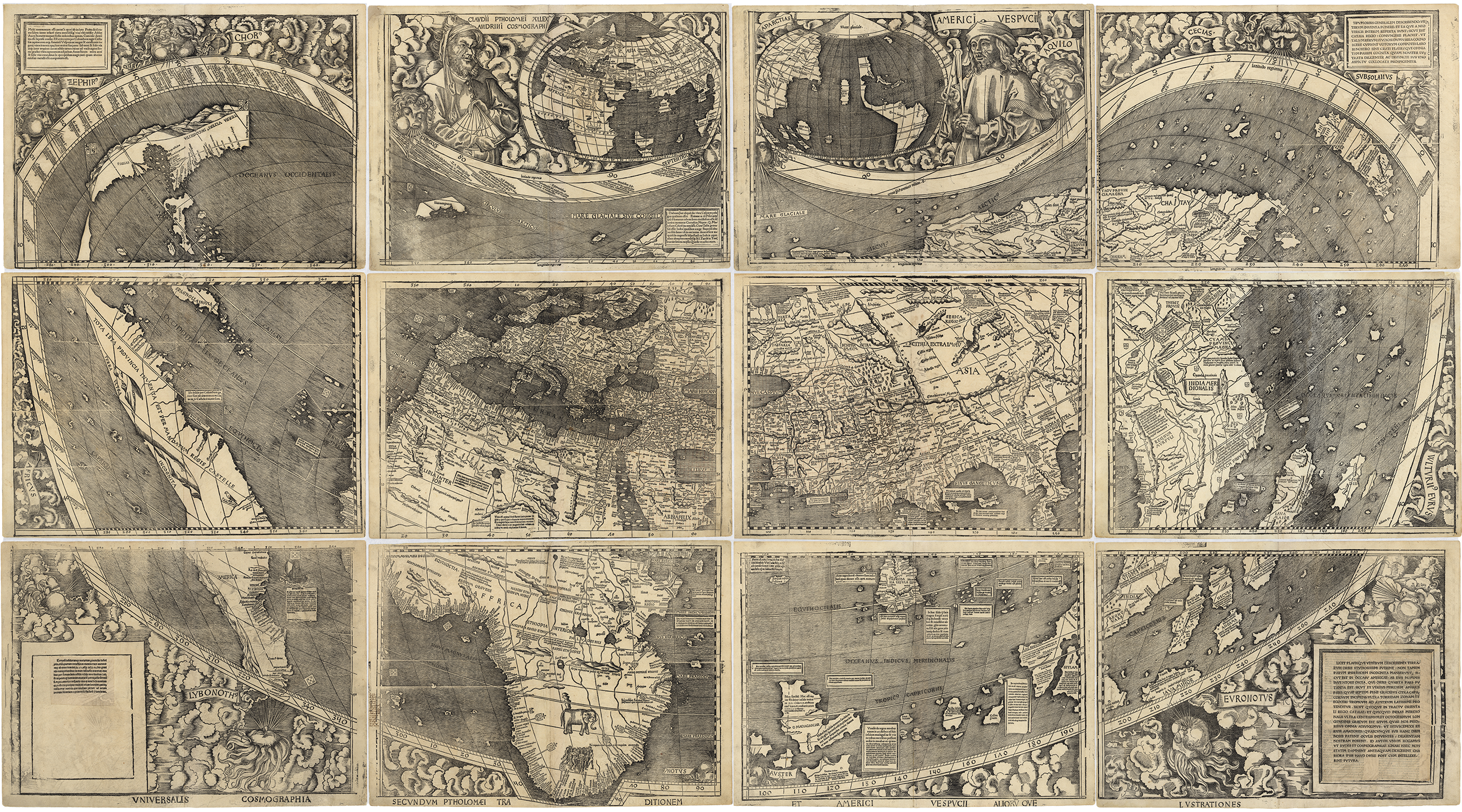

When Christopher Columbus died in 1506, he clung to the belief that he’d discovered the shores of Asia—in fact, he’d merely reached the Caribbean islands. Had he lived another year, a new world map by a German cartographer might have changed his mind.

In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller’s soon-to-be-famous map, based on Amerigo Vespucci’s more recent voyages, became the first to depict the land on the other side of the Atlantic as new continents—and to include a new ocean, later named the Pacific. In recognition of Vespucci’s exploits, Waldseemüller put his portrait on his map—top row, second panel from right—and christened the southern continent America, in the first recorded usage of the word. (Just 36 years later, Nicolaus Copernicus’s publication of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, also in the library’s collection, shook human perspective once again by placing the sun at the center of the solar system.)

Sometimes called “America’s birth certificate,” the only surviving first edition of the map is on permanent display at the library. Remarkably, the original woodblock-printed map was believed lost to history before its rediscovery in a German castle in 1901.

How to see it: The hermetically sealed map is displayed in the Thomas Jefferson Building.

Back to Top

Sounds of Earth

When the unmanned Voyager 1 and 2 space probes launched in the summer of 1977, identical 12-inch phonograph records titled Sounds of Earth were placed aboard each. Known as the “Golden Records” due to their distinctive gold plating, they’re intended to capture the diversity of life and culture on this planet—and maybe, just maybe, communicate something of our world to extraterrestrials.

Each disk contains recordings of Chuck Berry, Mozart, and traditional African music; sounds of nature and animal calls; and greetings in 55 languages. They also include 115 images—from our solar system’s planets to our DNA structure to the Great Wall of China. “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space,” Carl Sagan, who chaired the committee that chose the album’s contents, once said. “But the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

In 2012 and 2018, respectively, Voyagers 1 and 2 left our solar system and reached interstellar space—where both cosmic bottles and the recorded messages inside them remain the farthest human-made objects from Earth.

How to see it: The library’s copy of the recording is in its National Record Registry and can be listened to in its Treasures Gallery.

Back to Top

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an

When then–US representative Keith Ellison—the first Muslim elected to Congress—took his ceremonial oath of office in 2007, he placed his hand on a copy of the Qur’an that Thomas Jefferson bought in 1765. The library acquired Jefferson’s copy of the Muslim holy book as part of its purchase of 6,487 volumes from his personal library that remain in its holdings.

Jefferson obtained the book—a 1734 edition that was the first English version translated directly from Arabic—while a law student, and it marked the start of a lifelong interest in Islam. He later acquired numerous books on Middle Eastern history, languages, and law, and made notes on Islam as it related to English common law. Jefferson “had not very good things to say about either Catholicism or Judaism [or Islam],” Denise Spellberg, the author of Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders, told NPR. “But he insisted that these individual practitioners should have equal civil rights. . . . [He] resisted the notion, for example, that Catholics were a threat to the United States because of their allegiance to the pope as a foreign power.”

How to see it: The library does not make the book available to the public. Digital images of its two volumes are available via the Digital Rare Book Collections.

Back to Top

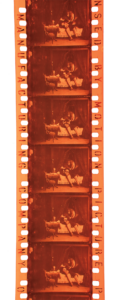

Frankenstein

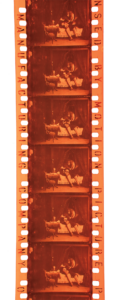

In 2015, the library acquired the sole surviving nitrate print of the first film adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. A 1910 American silent film written and directed by J. Searle Dawley, the 13-minute Frankenstein was produced by Edison Manufacturing Company, which was founded by—you guessed it—renowned inventor Thomas Edison.

Over a 24-year-run, the Edison company produced some 1,200 films. It promoted Frankenstein with a pitch that wouldn’t be out of place in the special-effects-obsessed Hollywood of today: “To those who are not familiar with the story, we can only say that the film tells an intensely dramatic story by the aid of some of the most remarkable photographic effects that have yet been attempted. The formation of the hideous monster from the blazing chemicals of a huge cauldron in Frankenstein’s laboratory is probably the most weird, mystifying, and fascinating scene ever shown on a film.”

Despite the studio’s claims, the first cinematic Frankenstein adaptation wasn’t quite the artistic breakthrough that the novel was. Still, its cultural significance endures.

How to see it: Viewable through the library’s online National Screening Room, which also shows digitized historical films, commercials, newsreels, and home movies of people including Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein.

Back to Top

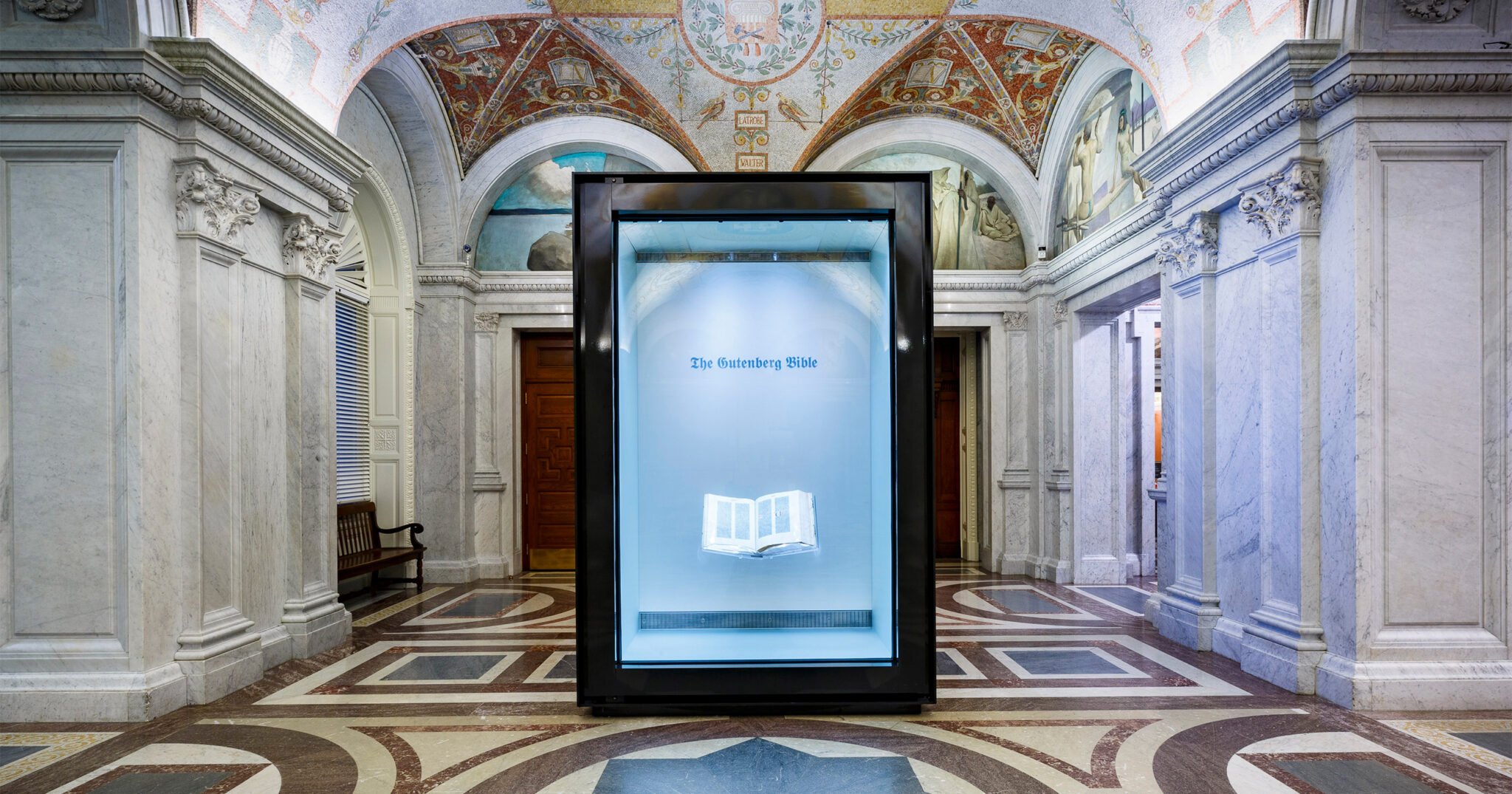

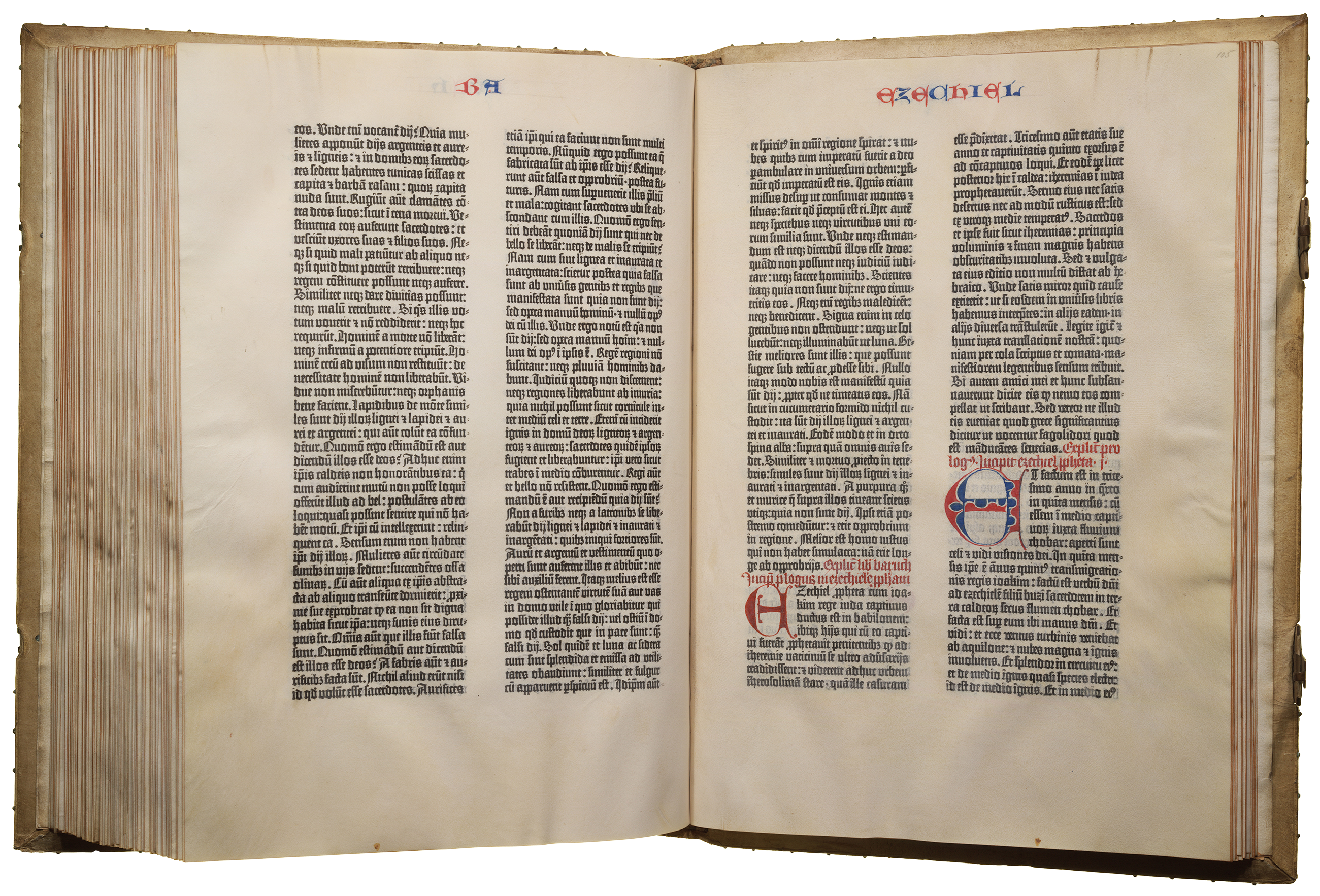

The Gutenberg Bible

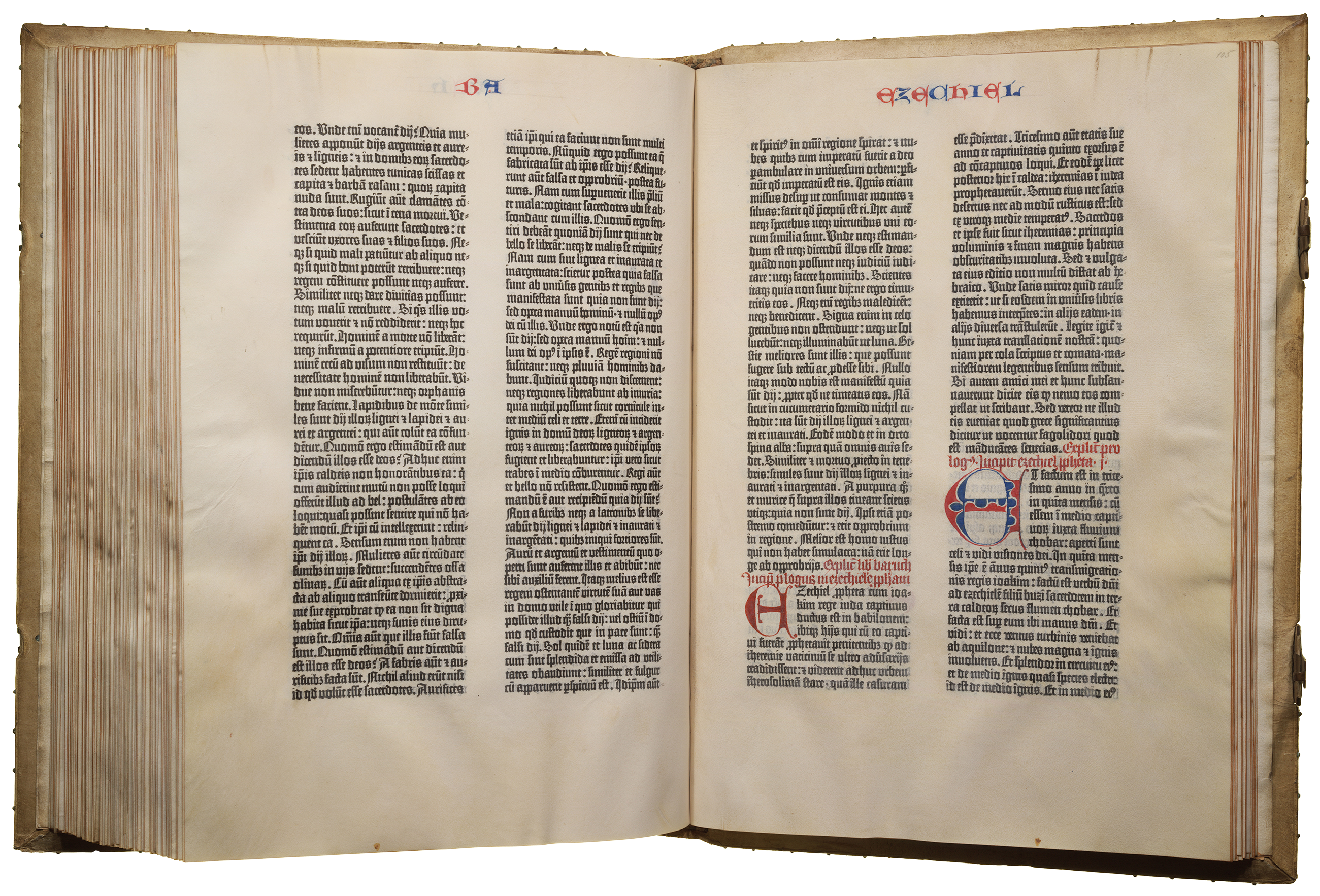

Made in the 1450s in what is now Germany, the Gutenberg Bible is revered for both its aesthetic qualities and its historical significance as the first major work mass-produced in Western Europe from movable metal type. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press was a technological breakthrough, helping usher Europe out of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution by allowing once-rare classical texts, scientific books, and other prints and engravings to be mass-produced and more widely distributed to the public. (Of course, human advancement seldom moves in a straight line: A witch-hunting manual became the era’s second-best-selling book.)

The library’s copy of the Gutenberg Bible is one of just three surviving complete versions printed on vellum (prepared calfskin) and bound in alum-tawed pigskin. After nearly 600 years, the richness of its oil-based ink—itself a breakthrough—and intricate, Gothic-lettered Latin script continues to amaze.

How to see it: On permanent display at the entrance to the Great Hall of the Jefferson Building.

Back to Top

Relics of a Tragedy

Soon after Confederate supporter John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865—just five days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox—the President was carried across the street to a boardinghouse. At his bedside when Lincoln took his final breath the next morning, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton is reported to have said, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

The contents of the President’s pockets, largely everyday items, were given to his son Robert. Among them: two pairs of eyeglasses, a white Irish-linen handkerchief embroidered with “A. Lincoln,” a button in need of resewing, a gold watch fob, an ivory-and-silver pocketknife, and a silk-lined leather wallet. In his wallet were multiple newspaper clippings—articles on Confederate Army unrest, emancipation in Missouri, and his presidency. The only currency? A five-dollar Confederate bill, likely a souvenir from recent Petersburg and Richmond trips.

The relics remained in Lincoln’s family until 1937, when his granddaughter donated them to the library. They were not exhibited, however, until 1976, when then–Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin decided that their display might humanize a man who had become “mythologically engulfed.”

How to see them: On display in the Treasures Gallery.

Back to Top

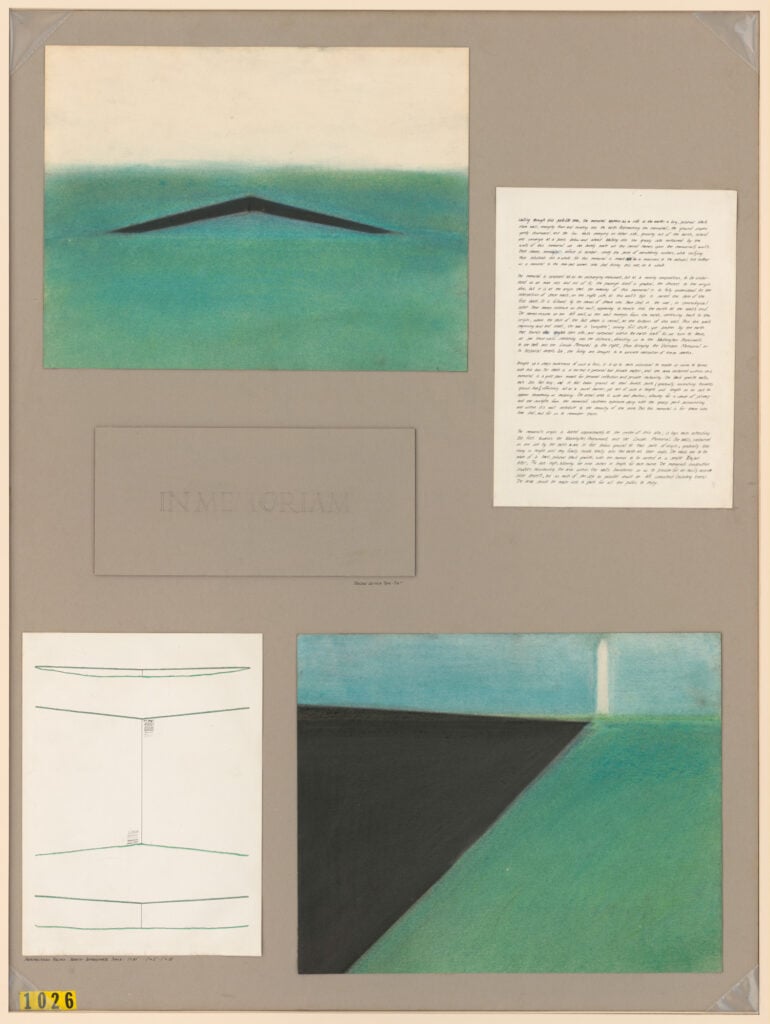

Proposal for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

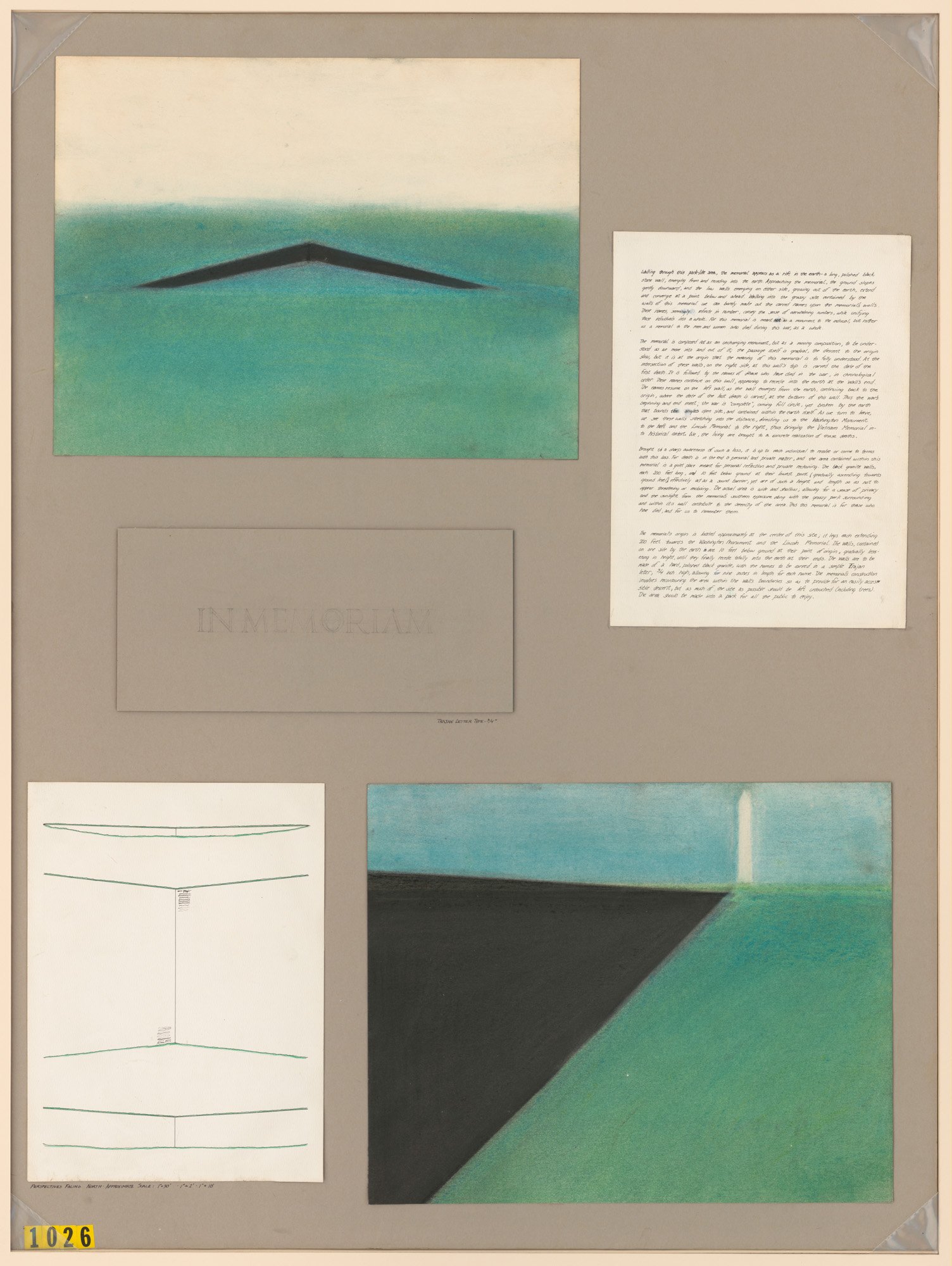

In 1981, Yale University School of Architecture undergraduate Maya Lin won the blind public design competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Chosen from more than 1,400 submissions, her austere conception—a reflective black granite wall bearing the names of more than 58,000 servicemembers who died in the conflict—became a profound symbol that helped heal the bitter national divisions over the war.

Lin’s winning proposal was initially controversial—in part because its minimalist design and dark color were perceived as casting a negative light on the war and its veterans, and in part because Lin was an inexperienced designer with a Chinese American background. But today, the site is the National Mall’s most visited memorial, drawing more than 5 million people annually.

Its V-shaped walls are aligned to the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, positioning the Vietnam War in the context of American history. While it’s often simply called “the Wall,” Lin conceived the memorial as splitting open the soil. “I had a simple impulse,” she once said, “to cut into the earth . . . an initial violence and pain that in time would heal.”

How to see it: High-resolution copies are available for download or via the library’s Duplication Services.

Back to Top

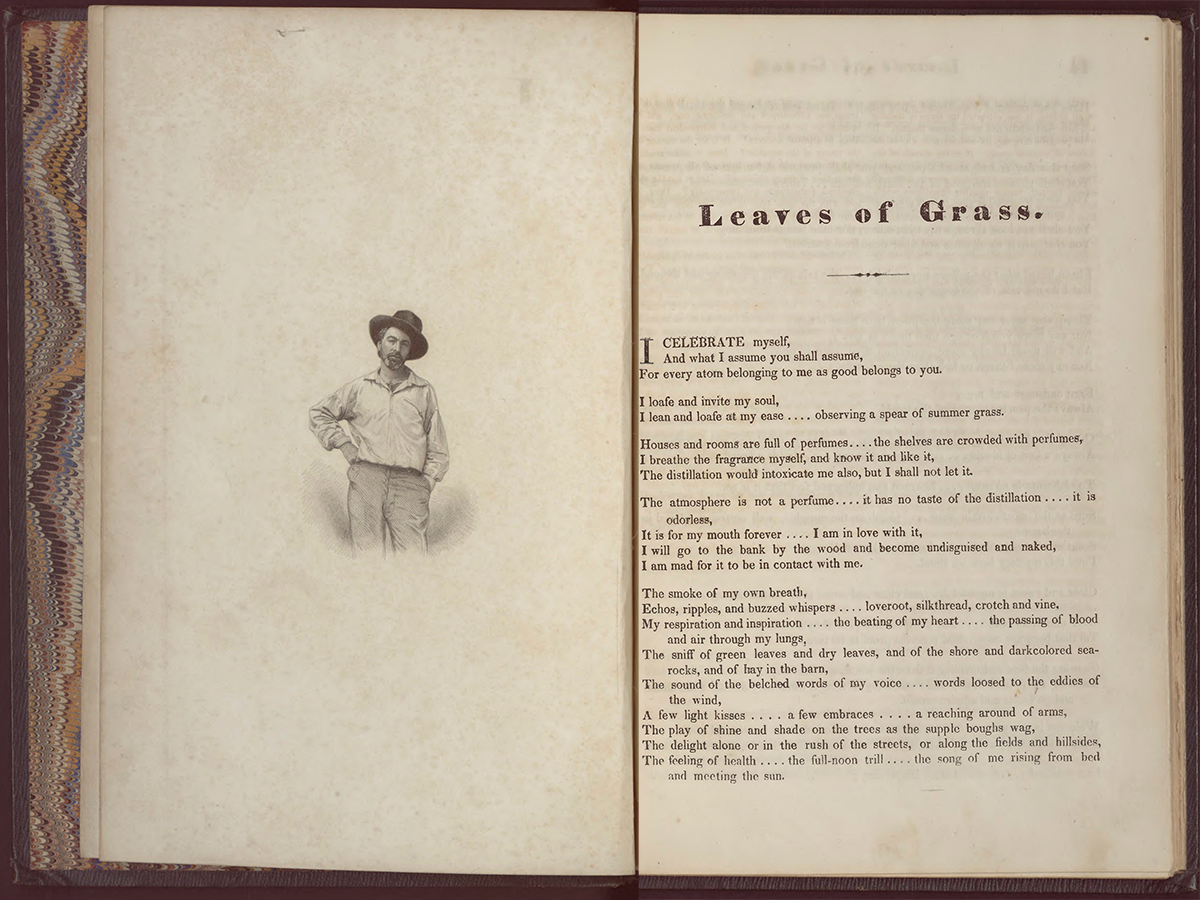

Leaves of Grass

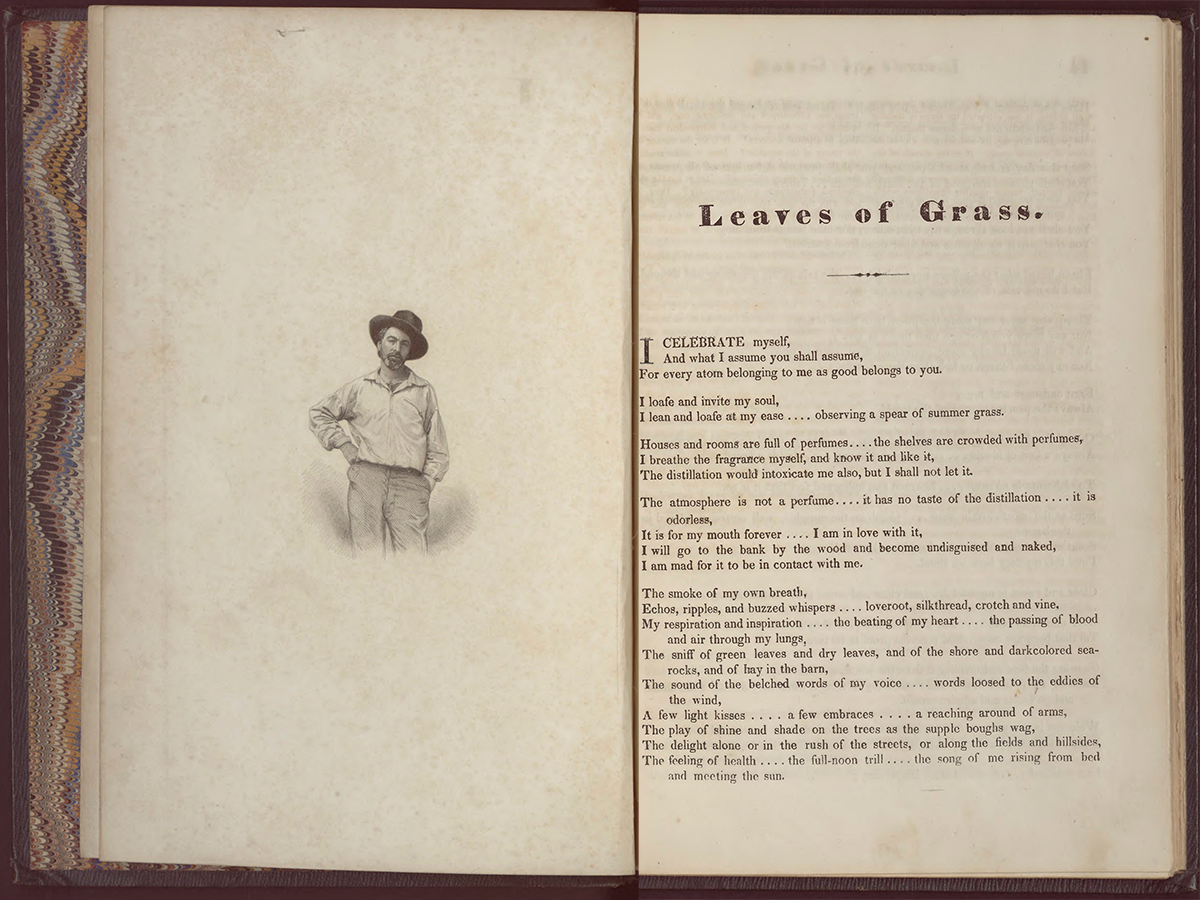

It’s hard to overstate the literary significance of Leaves of Grass, initially a slim volume of 12 poems when it was published in July 1855. Introducing the greatest American poet of the 19th century, Walt Whitman, this celebration of the individual and a still-young country has since remained at the heart of America’s sense of itself.

For the rest of his life, Whitman continually produced new editions of the book—revising lines, adding poems, renaming old ones, changing typography. Not until 1881 did he title its longest poem “Song of Myself.” By the time of the final edition in 1891–92, Leaves of Grass was thick with 400 individual works.

The library’s rare first edition was self-published by Whitman and does not have his name on the title page. Instead, he placed an engraving of himself dressed in carpenter’s clothes as “one of the roughs,” an image of the American poet as a working-class everyman. Later editions depicted an evolving Whitman, more worldly and esteemed, though for the book’s last printing, he reverted to a portrait of himself, taken in Boston, as a younger man while toiling on the 1860 edition.

How to see it: The book and other Whitman materials are available through the library’s digital collections and sometimes in exhibitions.

Back to Top

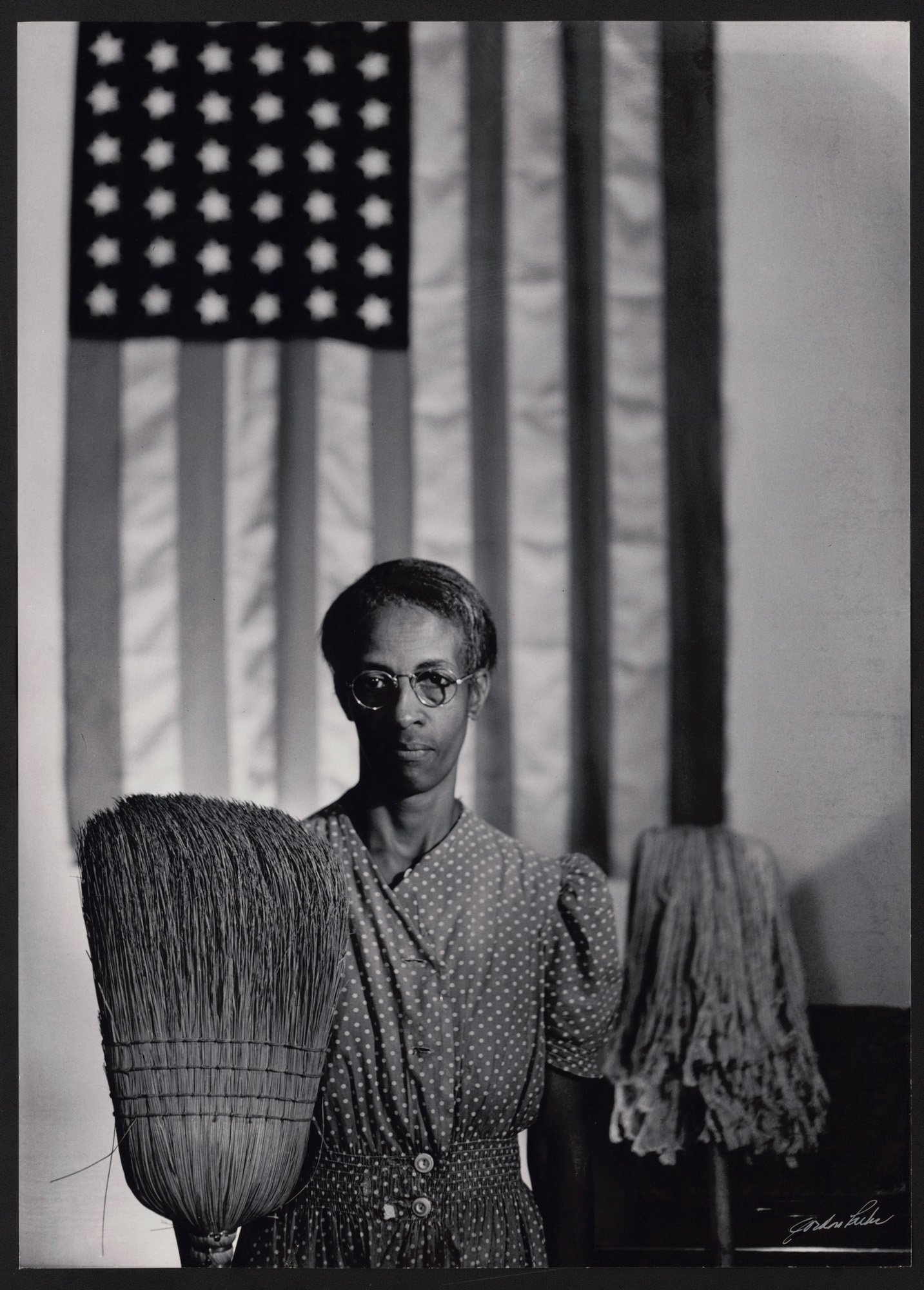

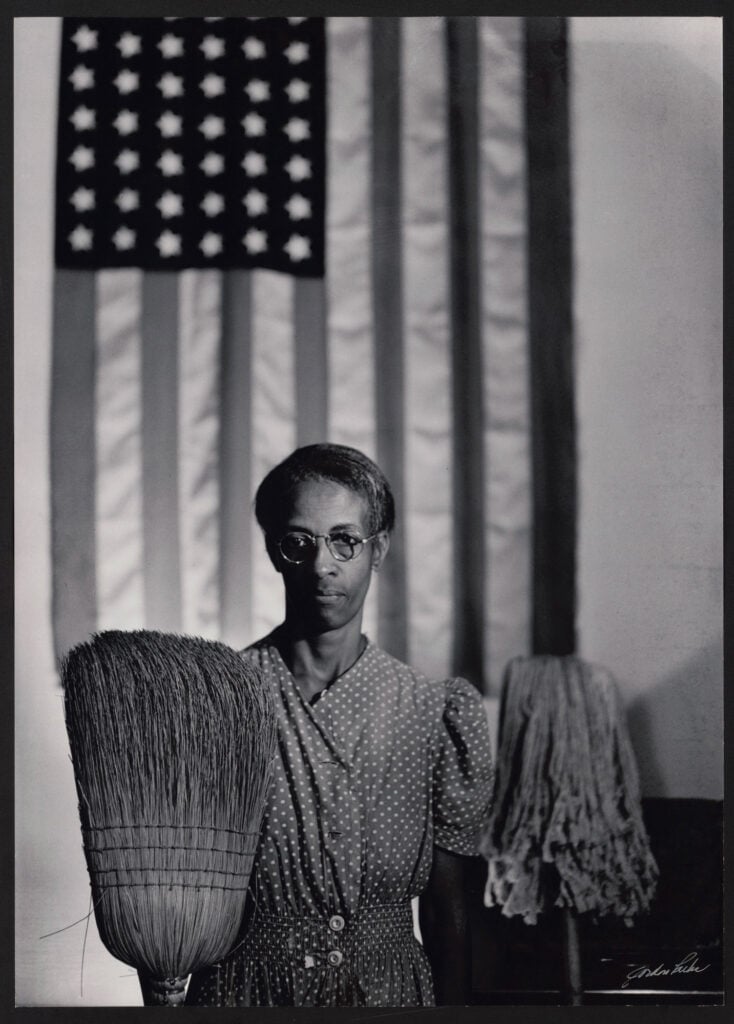

“American Gothic”

Coming to Washington in 1942 to work for the Farm Security Administration, photographer Gordon Parks wanted to document the city’s Black community, just as he’d previously done in Chicago. He soon got to know Ella Watson, a cleaning woman, visiting her at home and attending her church. Eventually, he asked if he could take her picture, posing her in the manner of the Iowa farmers in Grant Wood’s famous 1930 painting “American Gothic.”

“What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism, the evils of poverty, the discrimination and the bigotry,” Parks later said of his wide-ranging 1942–44 Farm Security Administration photo series, “by showing the people who suffered most under it.”

Born in the Midwest, Parks worked as a musician and waiter on passenger trains before teaching himself photography and ultimately becoming one of the 20th century’s most important photographers. The library holds many of his papers, documenting his career as a writer, photographer, and filmmaker. Though Parks had experienced racial prejudice before coming to the nation’s capital, the bigotry he found here was “worse than any place I had yet seen.”

How to see it: In the Prints and Photographs Division or as a free high-resolution download.

Back to Top

Stradivarius Instruments

In 1935, Washington philanthropist and renowned musical-soiree host Gertrude Clarke Whittall started the library’s collection of musical instruments by donating three violins, a viola, and a cello, all of them Stradivarius-stringed. Since then, the library has acquired other instruments, ranging from Siamese-style folk instruments donated by the king of Thailand in 1960 to James Madison’s crystal flute, the latter of which musician Lizzo famously played at the institution in 2022.

Typically, each instrument is given a nickname rooted in a related performer, owner, collector, or physical feature. The 1699 “Castelbarco” violin was once part of a quartet of Stradivarius instruments owned by Count Cesare Castelbarco of Milan, while the 1704 “Betts”—among the most legendary violins from Antonio Stradivari’s workshop—was once sold to a shop of the same name at the Royal Exchange in London.

Valued for their historical importance, the Stradivarius instruments still produce beautiful sound. Several times a year, professional musicians play them at library concerts open to the public.

How to see them: Several instruments can be viewed in the Jefferson Building’s Whittall Pavilion (appointment required).

Back to Top

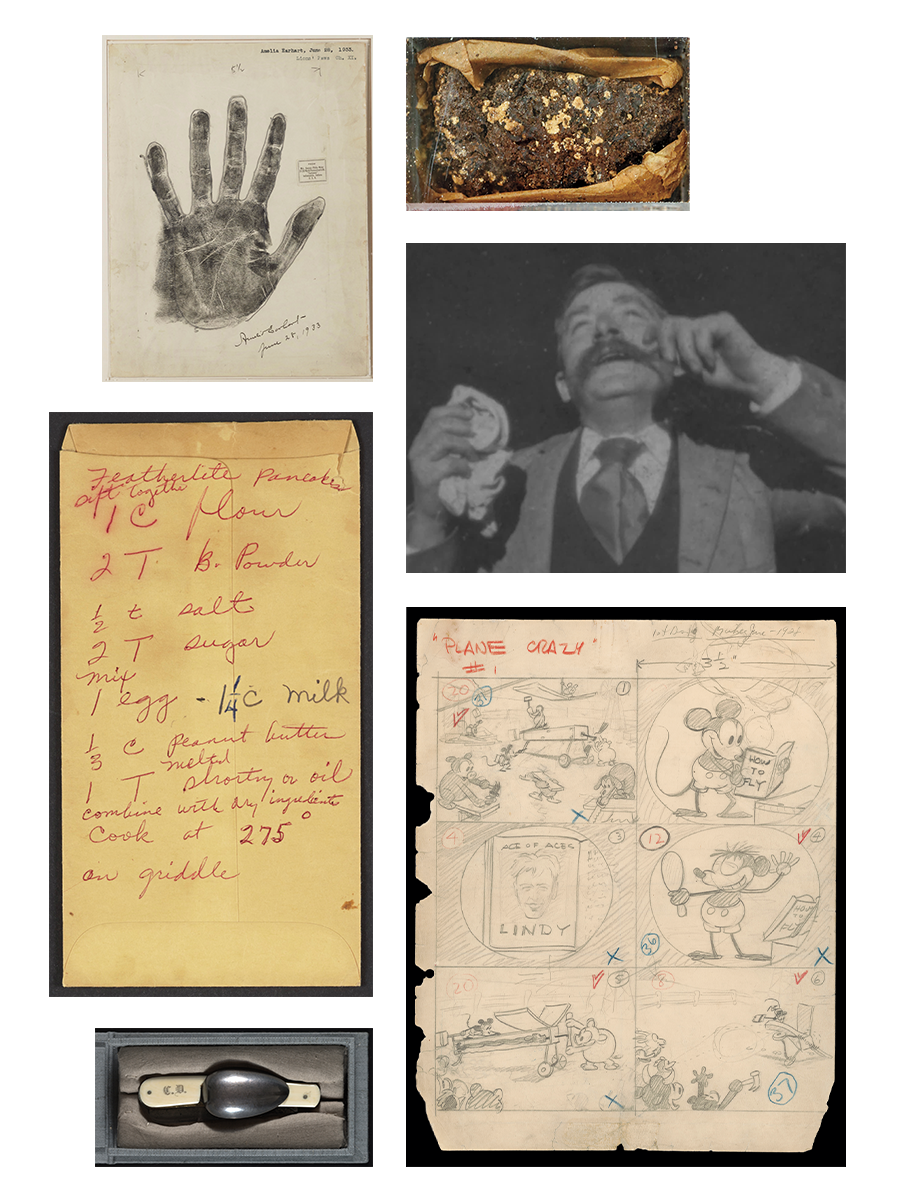

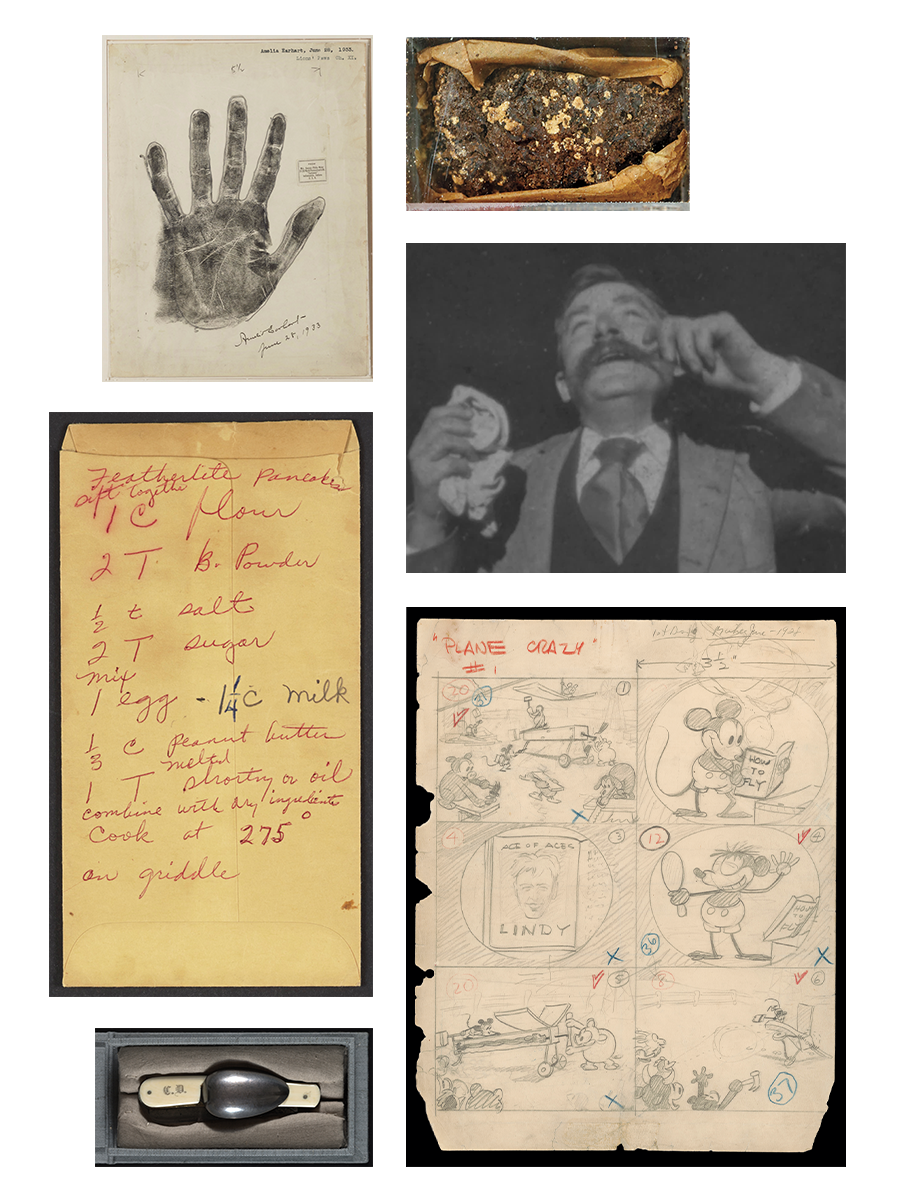

Strange Treasures

Some items in the Library of Congress’s collection are awe-inspiring. Others are more, uh, idiosyncratic.

Celebrity palm prints, including Amelia Earhart’s, prepared by famous socialite and palmist Nellie Simmons Meier.

Rosa Parks’s recipe for peanut-butter pancakes, written on the back of a bank envelope.

Charles Dickens’s traveling cutlery kit–including steel spoon, knife, and corkscrew–from his 1860s visit to America.

The largest collection of comics in the world, including the original Walt Disney storyboards for the first Mickey Mouse short ever produced

Fred Ott’s Sneeze, a five-second silent film from 1894 that’s the first motion picture copyrighted in the US

A moldy piece of wedding cake from General Tom Thumb’s 1863 nuptials to P.T. Barnum show costar Lavinia Warren–an event Barnum sold 5,000 tickets to.

1.

Celebrity palm prints, including Amelia Earhart’s, prepared by famous socialite and palmist Nellie Simmons Meier.

2.

A moldy piece of wedding cake from General Tom Thumb’s 1863 nuptials to P.T. Barnum show costar Lavinia Warren–an event Barnum sold 5,000 tickets to.

3.

Rosa Parks’s recipe for peanut-butter pancakes, written on the back of a bank envelope.

4.

Fred Ott’s Sneeze, a five-second silent film from 1894 that’s the first motion picture copyrighted in the US.

5.

Charles Dickens’s traveling cutlery kit–including steel spoon, knife, and corkscrew–from his 1860s visit to America.

6.

The largest collection of comics in the world, including the original Walt Disney storyboards for the first Mickey Mouse short ever produced.

7.

Locks of hair from Ludwig van Beethoven, Ulysses S. Grant, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, among others.

8.

A small stash of cocaine used by Dr. Carl Koller as a surgical anesthetic after Sigmund Freud encouraged him to experiment with it.

9.

Harry Houdini’s personal library of psychic phenomena, spiritualism, magic, witchcraft, demonology, and magic books, one of the largest such collections in the world.

10.

Every tweet from 2006 to 2017, documenting the first 12 years of Twitter.

uring the War of 1812, British troops famously torched the US Capitol, burning down the still-new home of the fledgling country’s legislative body. Also going up in flames? Roughly 3,000 books, largely about law, that made up the Library of Congress’s core collection.

Within a month, former President and noted bibliophile Thomas Jefferson offered his personal library as a replacement. His offer was warmly received by many in the House and Senate, but not by all. Massachusetts representative Cyrus King, an opposition Federalist, argued that Jefferson’s diverse holdings—which included works in Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, and Old English, as well as a translation of the Qur’an—would foster his “infidel philosophy” while being “in languages which many cannot read, and most ought not.”

The bill narrowly passed, along party lines, and Congress paid almost $24,000 for Jefferson’s 6,487 books. On May 8, 1815, as a final wagonload of books left Monticello, Jefferson wrote to Samuel Harrison Smith, who had helped facilitate the sale, that “an interesting treasure is added to . . . the depository of unquestionably the choicest collection of books in the U.S. and I hope it will not be without some general effect on the literature of our country.”

Jefferson eventually got his wish. Today, the Library of Congress is a national jewel. Its main building on Capitol Hill, opened in 1897 and later named for the Founding Father, is home to a domed Main Reading Room that endures as one of Washington’s most elegant spaces. Within the library’s collection of more than 178 million items, the world’s largest, are a number of incredible treasures—and across the following pages, we’ve highlighted some of our favorites.

More incredible still? Most of what the institution has to offer is accessible with a simple library card.

In many ways, the modern library is the brainchild of former Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Spofford, a visionary who lobbied Abraham Lincoln for the job and then stayed on through nine (!) Presidents. Spofford led construction of the Thomas Jefferson Building and a major expansion of the collection, working toward his broader goal of establishing a national library. He succeeded yet never lost sight of the institution’s original mission to serve legislators: For decades, the Jefferson Building and the Capitol were connected by an underground tunnel equipped with an electric book trolley and pneumatic message tubes. Lawmakers (or really, their staffers and pages) could send book requests to librarians via the tubes, and librarians could send books back via the trolley.

In the early 2000s, the book tunnel was demolished to make room for the underground Capitol Visitor Center. A separate, pedestrian-friendly tunnel now links the two buildings, where librarians can still be spotted wheeling book carts from time to time. That’s hardly the only way the library has evolved. Its physical collection is now housed in three Capitol Hill buildings and other facilities in Maryland and Virginia; its digital collection, begun in 1994, contains more than 900 million files; its collections of sounds, music, prints, moving images, and photographs date back more than 100 years and continue to grow alongside audiovisual media and communication.

In fact, the library adds more than 10,000 items each and every working day. Every year, it adds 25 recordings of “cultural, historical or aesthetic significance” to its National Recording Registry, through a nomination process that’s open to the public. A similar process annually expands the National Film Registry, which contains both Citizen Kane and Shrek. As former Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden puts it, the institution is a perpetual “work in progress,” much like the country it serves.

Speaking to Washingtonian this spring—before President Trump fired her in early May—Hayden said the library had recently acquired composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim’s papers, a victory in its friendly rivalry with the New York Public Library over arts and cultural acquisitions. Even among the library’s standing collections, new discoveries are sometimes made. To wit: A couple of years ago, using spectral-imaging processes, it was revealed that, in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson had originally written “our fellow subjects” before changing the phrase to “our fellow citizens.”

“What we like to highlight—and exhibit—is the process of creativity,” Hayden said. “Anybody can physically go into the building to sit down in a reading room. We have 16 spread out between the three buildings. You have the manuscripts; the bulk of that historic material; print and photographs; and the music, theater, and performing-arts divisions. You see really cool stuff.”

Visit the library at the right time, she added, and you may even catch someone you recognize in the throes of said creative process. “With all these wonderful resources, people who write books are often here,” she said, noting that acclaimed filmmaker Ken Burns “sits here for hours and hours doing research for every documentary that he does. He never fails to mention the library in his credits.”

Hayden smiled. “But if you are just a curious person, we want you to come, too.”

Back to Top

“America’s Birth Certificate”

When Christopher Columbus died in 1506, he clung to the belief that he’d discovered the shores of Asia—in fact, he’d merely reached the Caribbean islands. Had he lived another year, a new world map by a German cartographer might have changed his mind.

In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller’s soon-to-be-famous map, based on Amerigo Vespucci’s more recent voyages, became the first to depict the land on the other side of the Atlantic as new continents—and to include a new ocean, later named the Pacific. In recognition of Vespucci’s exploits, Waldseemüller put his portrait on his map—top row, second panel from right—and christened the southern continent America, in the first recorded usage of the word. (Just 36 years later, Nicolaus Copernicus’s publication of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, also in the library’s collection, shook human perspective once again by placing the sun at the center of the solar system.)

Sometimes called “America’s birth certificate,” the only surviving first edition of the map is on permanent display at the library. Remarkably, the original woodblock-printed map was believed lost to history before its rediscovery in a German castle in 1901.

How to see it: The hermetically sealed map is displayed in the Thomas Jefferson Building.

Back to Top

Sounds of Earth

When the unmanned Voyager 1 and 2 space probes launched in the summer of 1977, identical 12-inch phonograph records titled Sounds of Earth were placed aboard each. Known as the “Golden Records” due to their distinctive gold plating, they’re intended to capture the diversity of life and culture on this planet—and maybe, just maybe, communicate something of our world to extraterrestrials.

Each disk contains recordings of Chuck Berry, Mozart, and traditional African music; sounds of nature and animal calls; and greetings in 55 languages. They also include 115 images—from our solar system’s planets to our DNA structure to the Great Wall of China. “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space,” Carl Sagan, who chaired the committee that chose the album’s contents, once said. “But the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

In 2012 and 2018, respectively, Voyagers 1 and 2 left our solar system and reached interstellar space—where both cosmic bottles and the recorded messages inside them remain the farthest human-made objects from Earth.

How to see it: The library’s copy of the recording is in its National Record Registry and can be listened to in its Treasures Gallery.

Back to Top

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an

When then–US representative Keith Ellison—the first Muslim elected to Congress—took his ceremonial oath of office in 2007, he placed his hand on a copy of the Qur’an that Thomas Jefferson bought in 1765. The library acquired Jefferson’s copy of the Muslim holy book as part of its purchase of 6,487 volumes from his personal library that remain in its holdings.

Jefferson obtained the book—a 1734 edition that was the first English version translated directly from Arabic—while a law student, and it marked the start of a lifelong interest in Islam. He later acquired numerous books on Middle Eastern history, languages, and law, and made notes on Islam as it related to English common law. Jefferson “had not very good things to say about either Catholicism or Judaism [or Islam],” Denise Spellberg, the author of Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders, told NPR. “But he insisted that these individual practitioners should have equal civil rights. . . . [He] resisted the notion, for example, that Catholics were a threat to the United States because of their allegiance to the pope as a foreign power.”

How to see it: The library does not make the book available to the public. Digital images of its two volumes are available via the Digital Rare Book Collections.

Back to Top

Frankenstein

In 2015, the library acquired the sole surviving nitrate print of the first film adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. A 1910 American silent film written and directed by J. Searle Dawley, the 13-minute Frankenstein was produced by Edison Manufacturing Company, which was founded by—you guessed it—renowned inventor Thomas Edison.

Over a 24-year-run, the Edison company produced some 1,200 films. It promoted Frankenstein with a pitch that wouldn’t be out of place in the special-effects-obsessed Hollywood of today: “To those who are not familiar with the story, we can only say that the film tells an intensely dramatic story by the aid of some of the most remarkable photographic effects that have yet been attempted. The formation of the hideous monster from the blazing chemicals of a huge cauldron in Frankenstein’s laboratory is probably the most weird, mystifying, and fascinating scene ever shown on a film.”

Despite the studio’s claims, the first cinematic Frankenstein adaptation wasn’t quite the artistic breakthrough that the novel was. Still, its cultural significance endures.

How to see it: Viewable through the library’s online National Screening Room, which also shows digitized historical films, commercials, newsreels, and home movies of people including Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein.

Back to Top

The Gutenberg Bible

Made in the 1450s in what is now Germany, the Gutenberg Bible is revered for both its aesthetic qualities and its historical significance as the first major work mass-produced in Western Europe from movable metal type. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press was a technological breakthrough, helping usher Europe out of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution by allowing once-rare classical texts, scientific books, and other prints and engravings to be mass-produced and more widely distributed to the public. (Of course, human advancement seldom moves in a straight line: A witch-hunting manual became the era’s second-best-selling book.)

The library’s copy of the Gutenberg Bible is one of just three surviving complete versions printed on vellum (prepared calfskin) and bound in alum-tawed pigskin. After nearly 600 years, the richness of its oil-based ink—itself a breakthrough—and intricate, Gothic-lettered Latin script continues to amaze.

How to see it: On permanent display at the entrance to the Great Hall of the Jefferson Building.

Back to Top

Relics of a Tragedy

Soon after Confederate supporter John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865—just five days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox—the President was carried across the street to a boardinghouse. At his bedside when Lincoln took his final breath the next morning, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton is reported to have said, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

The contents of the President’s pockets, largely everyday items, were given to his son Robert. Among them: two pairs of eyeglasses, a white Irish-linen handkerchief embroidered with “A. Lincoln,” a button in need of resewing, a gold watch fob, an ivory-and-silver pocketknife, and a silk-lined leather wallet. In his wallet were multiple newspaper clippings—articles on Confederate Army unrest, emancipation in Missouri, and his presidency. The only currency? A five-dollar Confederate bill, likely a souvenir from recent Petersburg and Richmond trips.

The relics remained in Lincoln’s family until 1937, when his granddaughter donated them to the library. They were not exhibited, however, until 1976, when then–Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin decided that their display might humanize a man who had become “mythologically engulfed.”

How to see them: On display in the Treasures Gallery.

Back to Top

Proposal for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

In 1981, Yale University School of Architecture undergraduate Maya Lin won the blind public design competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Chosen from more than 1,400 submissions, her austere conception—a reflective black granite wall bearing the names of more than 58,000 servicemembers who died in the conflict—became a profound symbol that helped heal the bitter national divisions over the war.

Lin’s winning proposal was initially controversial—in part because its minimalist design and dark color were perceived as casting a negative light on the war and its veterans, and in part because Lin was an inexperienced designer with a Chinese American background. But today, the site is the National Mall’s most visited memorial, drawing more than 5 million people annually.

Its V-shaped walls are aligned to the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, positioning the Vietnam War in the context of American history. While it’s often simply called “the Wall,” Lin conceived the memorial as splitting open the soil. “I had a simple impulse,” she once said, “to cut into the earth . . . an initial violence and pain that in time would heal.”

How to see it: High-resolution copies are available for download or via the library’s Duplication Services.

Back to Top

Leaves of Grass

It’s hard to overstate the literary significance of Leaves of Grass, initially a slim volume of 12 poems when it was published in July 1855. Introducing the greatest American poet of the 19th century, Walt Whitman, this celebration of the individual and a still-young country has since remained at the heart of America’s sense of itself.

For the rest of his life, Whitman continually produced new editions of the book—revising lines, adding poems, renaming old ones, changing typography. Not until 1881 did he title its longest poem “Song of Myself.” By the time of the final edition in 1891–92, Leaves of Grass was thick with 400 individual works.

The library’s rare first edition was self-published by Whitman and does not have his name on the title page. Instead, he placed an engraving of himself dressed in carpenter’s clothes as “one of the roughs,” an image of the American poet as a working-class everyman. Later editions depicted an evolving Whitman, more worldly and esteemed, though for the book’s last printing, he reverted to a portrait of himself, taken in Boston, as a younger man while toiling on the 1860 edition.

How to see it: The book and other Whitman materials are available through the library’s digital collections and sometimes in exhibitions.

Back to Top

“American Gothic”

Coming to Washington in 1942 to work for the Farm Security Administration, photographer Gordon Parks wanted to document the city’s Black community, just as he’d previously done in Chicago. He soon got to know Ella Watson, a cleaning woman, visiting her at home and attending her church. Eventually, he asked if he could take her picture, posing her in the manner of the Iowa farmers in Grant Wood’s famous 1930 painting “American Gothic.”

“What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism, the evils of poverty, the discrimination and the bigotry,” Parks later said of his wide-ranging 1942–44 Farm Security Administration photo series, “by showing the people who suffered most under it.”

Born in the Midwest, Parks worked as a musician and waiter on passenger trains before teaching himself photography and ultimately becoming one of the 20th century’s most important photographers. The library holds many of his papers, documenting his career as a writer, photographer, and filmmaker. Though Parks had experienced racial prejudice before coming to the nation’s capital, the bigotry he found here was “worse than any place I had yet seen.”

How to see it: In the Prints and Photographs Division or as a free high-resolution download.

Back to Top

Stradivarius Instruments

In 1935, Washington philanthropist and renowned musical-soiree host Gertrude Clarke Whittall started the library’s collection of musical instruments by donating three violins, a viola, and a cello, all of them Stradivarius-stringed. Since then, the library has acquired other instruments, ranging from Siamese-style folk instruments donated by the king of Thailand in 1960 to James Madison’s crystal flute, the latter of which musician Lizzo famously played at the institution in 2022.

Typically, each instrument is given a nickname rooted in a related performer, owner, collector, or physical feature. The 1699 “Castelbarco” violin was once part of a quartet of Stradivarius instruments owned by Count Cesare Castelbarco of Milan, while the 1704 “Betts”—among the most legendary violins from Antonio Stradivari’s workshop—was once sold to a shop of the same name at the Royal Exchange in London.

Valued for their historical importance, the Stradivarius instruments still produce beautiful sound. Several times a year, professional musicians play them at library concerts open to the public.

How to see them: Several instruments can be viewed in the Jefferson Building’s Whittall Pavilion (appointment required).

Back to Top

Strange Treasures

Some items in the Library of Congress’s collection are awe-inspiring. Others are more, uh, idiosyncratic.

Celebrity palm prints, including Amelia Earhart’s, prepared by famous socialite and palmist Nellie Simmons Meier.

Rosa Parks’s recipe for peanut-butter pancakes, written on the back of a bank envelope.

Charles Dickens’s traveling cutlery kit–including steel spoon, knife, and corkscrew–from his 1860s visit to America.

The largest collection of comics in the world, including the original Walt Disney storyboards for the first Mickey Mouse short ever produced

Fred Ott’s Sneeze, a five-second silent film from 1894 that’s the first motion picture copyrighted in the US

A moldy piece of wedding cake from General Tom Thumb’s 1863 nuptials to P.T. Barnum show costar Lavinia Warren–an event Barnum sold 5,000 tickets to.

1.

Celebrity palm prints, including Amelia Earhart’s, prepared by famous socialite and palmist Nellie Simmons Meier.

2.

A moldy piece of wedding cake from General Tom Thumb’s 1863 nuptials to P.T. Barnum show costar Lavinia Warren–an event Barnum sold 5,000 tickets to.

3.

Rosa Parks’s recipe for peanut-butter pancakes, written on the back of a bank envelope.

4.

Fred Ott’s Sneeze, a five-second silent film from 1894 that’s the first motion picture copyrighted in the US.

5.

Charles Dickens’s traveling cutlery kit–including steel spoon, knife, and corkscrew–from his 1860s visit to America.

6.

The largest collection of comics in the world, including the original Walt Disney storyboards for the first Mickey Mouse short ever produced.

7.

Locks of hair from Ludwig van Beethoven, Ulysses S. Grant, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, among others.

8.

A small stash of cocaine used by Dr. Carl Koller as a surgical anesthetic after Sigmund Freud encouraged him to experiment with it.

9.

Harry Houdini’s personal library of psychic phenomena, spiritualism, magic, witchcraft, demonology, and magic books, one of the largest such collections in the world.

10.

Every tweet from 2006 to 2017, documenting the first 12 years of Twitter.

This article appears in the July 2025 issue of Washingtonian.