DC’s top seed oil lobbyist is a man named Devin Mogler, the president and CEO of the National Oilseed Processors Association. This tends not to be a hot-button role, running a small trade group that represents US producers of canola, soy, safflower, sunflower, and flax oils. But Mogler started his job in January, right before Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was sworn in as health secretary.

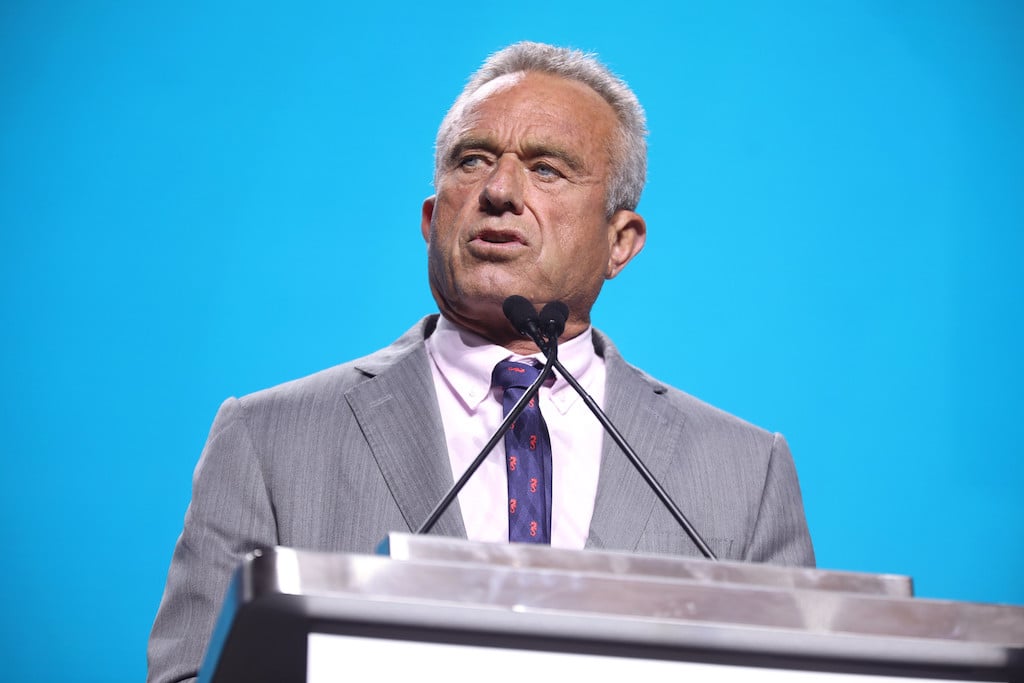

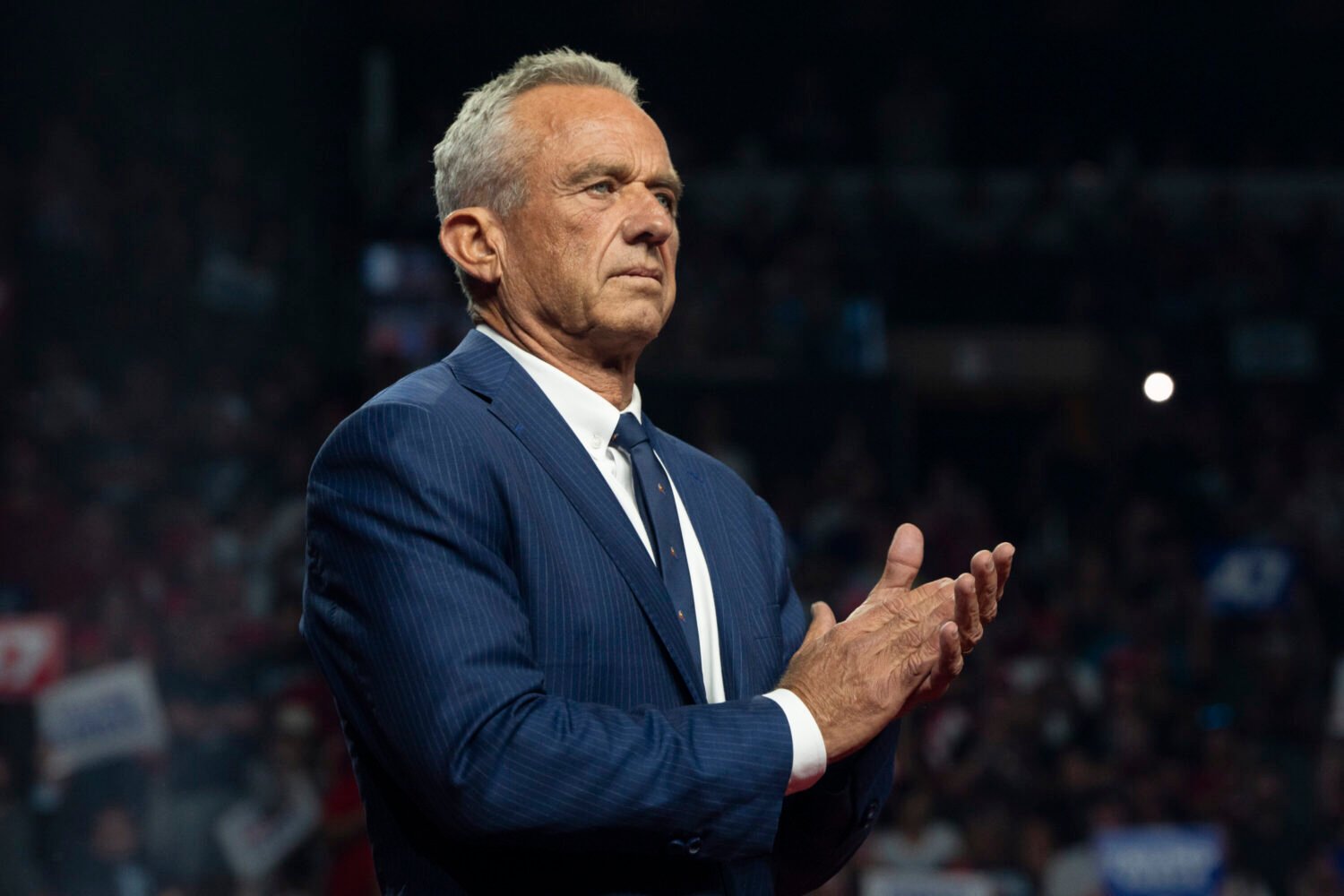

Kennedy has accused seed oils, the subcategory of vegetable oils made from plant seeds, of poisoning Americans, claiming that they’re driving the obesity epidemic, causing inflammation, and contributing to chronic disease. Research suggests that seed oils are fine—good, even, given that they’re lower in saturated fats than animal-based options like butter, tallow, or lard. Nonetheless, flanked by an online army of wellness influencers and fitness gurus and doctors-who-are-actually-chiropractors, RFK Jr.’s Make America Healthy Again movement has waged war on seed oils, and Mogler is on the front lines.

“Back in January or February, everyone was just like, ‘What do we even do? This is crazy. Nothing makes sense,’” Mogler told me in late July, wearing a salmon-pink suit and looking peeved. “That’s the frustrating thing for us, we’ve got reams and reams of peer-reviewed studies that all show that seed oils are not only safe, they are healthy. But we’re dealing with people who are not afraid to go off script, open up the playbook and do something radical, just to shake things up.”

He’s describing the Trump administration, various members of which have been stoking the seed oil panic. In March, RFK Jr. went on Hannity and discussed chronic disease over a plate of seed-oil-free French fries from a Florida Steak ‘n Shake. In June, on Fox & Friends, FDA commissioner Marty Makary decried the use of seed oils in infant formula, listing them alongside corn syrup and heavy metals as undesirable ingredients. And Casey Means, the current nominee for Surgeon General, has also written and spoken about the alleged dangers of seed oils. (“I read her book, unfortunately,” Mogler said.) Last September, Means told Megyn Kelly—another seed oil skeptic—that consuming these oils is essentially “eating engine lubricant.”

It’s true that seed oils are often found in unhealthy foods. Almost all packaged, ultra-processed goods (Pop Tarts, candy bars, potato chips, salad dressings) contain them, because they’re relatively shelf stable and have a neutral taste. But the scientific consensus is that the oils themselves aren’t the problem—and, in fact, can be healthier alternatives to animal fats, particularly for the heart. “This is one of the more studied topics in nutrition,” Christopher Gardner, a professor of medicine at Stanford, told an NPR reporter in July. “ So it’s extra bewildering to quite a few of us in the field that this [misinformation] is coming up.”

MAHA crusaders are fixated on the “hateful eight” seed oils (canola, corn, soy, sunflower, safflower, rice bran, cottonseed, and grapeseed), and the movement’s waxing political power presents a regulatory threat to the industry (think labeling laws that stigmatize seed oils, or banning them from federal nutrition programs). But the cultural problem—the “long-term disparagement of the product,” as Mogler put it—is possibly worse. Tom Hance, president of the US Canola Association, explained that when Americans scroll past misinformation online, “it plants that seed—for lack of a better word—that there’s a negative aspect to these vegetable oils.” Mogler said the industry is “not excited about the trends in consumer perceptions. I mean, a couple years ago, no one had heard the term ‘seed oils,’ and now it’s in the common vernacular, so we do have a concern about that.”

Mogler’s big fear is that seed oils could become like high-fructose corn syrup—an agricultural commodity that became stigmatized over wellness concerns, leading to plummeting demand. (“But isn’t corn syrup actually bad for you?” I asked, and he clammed up: “I’m not going to speak to that. My family raises corn. A number of our member companies also produce it. We work closely with the corn refiners. We’re for all of agriculture.”)

As of right now, demand for seed oils is stable—but major companies have begun to make changes. Since January, Sweetgreen has announced a seed oil-free menu, Steak ‘n Shake “RFKed” its fries by moving from vegetable oil to beef tallow, and PepsiCo and Starbucks both announced they were looking at a shift toward avocado and olive oil in some of their products. Hance believes that these companies are choosing fats based on consumer fads, not health and nutrition; “They’re following that mantra that the customer is always right, even if the customer is wrong.”

Lobbyists like Hance and Mogler plan to meet directly with corporations to shore up support for their industry. Mogler is hopeful about that approach, in part because it’s expensive to reformulate a product with different fats, and the result wouldn’t necessarily be healthier. Reminding food manufacturers of this, Mogler says, might help them “have the intestinal fortitude not to knee-jerk reformulate,” but he also hopes these companies—with their huge marketing budgets—might do the kind of pro-seed oils public relations campaign that small trade groups can’t afford.

And of course, as lobbyists, Hance and Mogler are spending lots of time on the Hill. Mogler said those meetings tend to go well, particularly with lawmakers from agricultural regions who don’t want to alienate farmers. At the state level, though, the landscape is more problematic. Louisiana just passed a labeling law that requires restaurants to disclose if they’re using seed oils. (“It’s Louisiana!” Mogler said, indignant. “They fry everything!”) California and Texas are also making some regulatory noise. To Mogler and Hance, it all feels exhausting: fighting policy battles, placating corporations, educating consumers, and combating misinformation online. “We don’t have the resources to engage at all these levels,” Mogler said of the National Oilseed Processors Association. “There’s only four of us here.”

When I remarked to Mogler that this is a tough moment to be a seed oil lobbyist, he joked that at least it’s job security. And Hance, Washington’s top canola guy, acknowledged sheepishly that he has a difficult role. Of the MAHA seed oil panic, he said that the industry is “certainly not taking for granted that it’s just going to die out on its own. But we believe we have the facts on our side, so that’s the better place to be.”