Arch Campbell and Pat Collins are two of DC’s more prominent retired TV news figures, and though they were colleagues at NBC4, these days they’re embroiled in a (friendly) literary rivalry: They’re competing to see who can sell more copies of his memoir at Politics and Prose. “I’ve been friends with him for decades, so we’re always needling each other,” Campbell says. “We have been trading sales figures, and I’m encroaching, right behind him. If he turns around, he’ll see me carting a box of books to some event so I can sell them out of my trunk.”

The minor twist here is that neither Campbell nor Collins actually has a book deal: Politics and Prose isn’t just selling the memoirs, it’s printing them. The longtime independent bookseller on Connecticut Avenue runs an in-house publishing operation, called Opus, that allows authors to self-publish their work. This side business has by some metrics been a huge success. Lately, there’s been a waitlist of nearly a year for Opus’s services. Apparently—perhaps unsurprisingly—a whole lot of amateur authors live in upper Northwest DC.

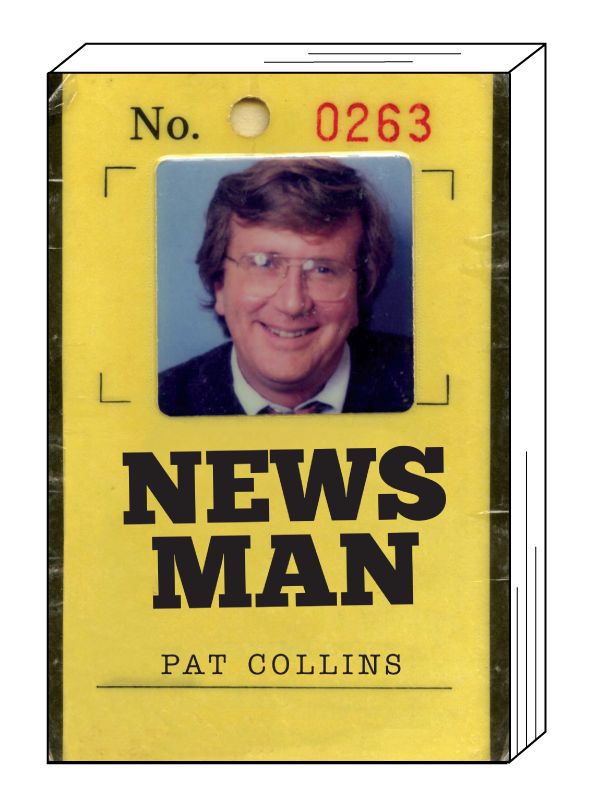

So far, Collins is at the top of that pile, sales-wise. The recently retired TV personality, famed for his “snow stick,” is Opus’s bestselling author, with more than 1,300 copies of his book, Newsman, sold so far. That isn’t a big number by Penguin Random House standards, but Collins gets to keep a lot more of the money. The book—which Opus’s designer decorated with Collins’s old press credentials—details some of his scoops, from the unsolved murders he can’t shake to the much-memed segment in which he wore a grape costume.

Opus tends to attract accomplished, retired locals with long memoir manuscripts and little interest from—or connections to—the traditional publishing world. But it has also published photography monographs, historical novels, cookbooks, and other types of work. “They’re passion projects,” says Ellie Maranda, who runs the publishing operation. “Nobody that comes to Opus is an author by profession.”

And yet Opus isn’t an ordinary self-publishing business, primarily because it’s associated with Washington’s most prominent indie bookstore. Opus offerings line a well-positioned display case near the front window, each with a bar code, blurbs, and a smartly designed cover. (Politics and Prose keeps a small portion of revenue from these sales.) Authors pay for that positioning, as well as for having the book designed, printed, and sold in the store for a year. The cost of the mid-tier package recently went up from $599 to $1,000, which includes books with an ISBN, the industry number that allows them to be sold in stores. A $1,200 “presidential” package includes marketing fliers, an invitation to speak at an author event, and recommendation slips that help sell the books to browsers.

Self-publishers don’t tend to have a stellar reputation. Historically, so-called vanity presses have been a last resort for writers who couldn’t interest a “real” publisher in their work. That has changed in recent years, with a whole industry of independent writers now selling books directly to readers—and pocketing all the revenue instead of a small fraction. But many readers remain dismissive of self-published books, because mainstream publishing houses don’t seem to deem them worthy of notice and—often—no professional editors have tempered or trimmed them.

On the other hand, the internet has led to an explosion of self-publishing, and book-length works released through services like Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing can often find large and enthusiastic audiences. The number of author-published titles with ISBNs is on the rise, having more than doubled in the past decade at the same time as the number of traditional titles published each year has fallen. Publishing houses have signed huge deals with genre authors whose work was originally self-released, like superstar novelist Colleen Hoover.

Much of Opus’s output bears the hallmarks of self-published work, such as indulgent page counts and occasionally odd turns of phrase. But the eclectic Opus roster can also often be genuinely interesting, as with an anthology of DC women writers edited by American University literature professor Melissa Scholes Young or a memoir by former Louisville mayor Harvey Sloane. And many of these authors simply want to hold the book in their hands, send copies to friends and family, maybe sell a few books to neighbors and readers who might happen to find the topic of interest. “It’s a lot of really personal things,” Maranda says. “Sometimes it’s just a way of passing down stories—almost like a family heirloom.”

Opus is run from a single desk tucked into a nook off of the fiction room of Politics and Prose’s flagship Connecticut Avenue store. You can usually find Maranda there, busy working on one of the 40 or so books the publisher will put out by the end of the year. A Midwesterner who graduated from the University of Iowa last year, Maranda is relatively new to the job, but she has quickly adjusted to her authors’ needs. “The clientele is a lot of older people,” she says, “and they like that I help them every step of the way.” She doesn’t do any revising of the text; writers have to hire their own editors if that’s a service they want. But she does format the pages, lay out photos, and design covers. The finished books don’t look exactly like the product of a major publisher, but they’re pretty close. Customers might not even realize what they’re buying.

That wouldn’t have been the case back in 2011, when Politics and Prose began its experiment with self-publishing. At the time, Bradley Graham and Lissa Muscatine had recently bought the store, and they learned about something called an Espresso machine. “It had nothing to do with coffee,” Graham says. “It was a machine that printed books.”

On Demand Books, the inventor of the Espresso Book Machine, had plans to lease them out to bookstores and libraries across the country. Customers would be able to have books manufactured right in front of them. Politics and Prose was one of the few places that went for the idea, and soon it was using one of the machines for a new self-publishing operation that it called Opus. The Espresso looked like a big office copier attached to a transparent washing machine; you could watch it crank out a bound copy of a book in less than seven minutes.

It turned out that the Espresso broke down often, emitted a strange inky smell, and didn’t earn nearly as much as it cost to lease. When their five-year agreement with On Demand Books ended, Graham and Muscatine opted not to renew it. (Last year, the company went out of business.)

But the Opus concept stuck. With conventional publishers consolidating and downsizing, Graham and Muscatine believed there was space in the market—and the store—for authors who might previously have gotten book deals but were struggling to get their work out there. They contracted with a company to handle the printing; cover design and marketing were handled in-house.

Opus has now released almost 400 titles, with many more on the way. The operation still isn’t profitable, but Graham says it loses less money than the Espresso did. What Opus does provide is community-building—another way to connect with the store’s book-loving neighbors. In a way, it’s not dissimilar to the store’s popular basement cafe, or even its author readings, which move units but also provide a gathering place for literary locals. “We have always believed that we exist not just to sell stuff,” Graham says. “I think people choose Opus for the same reasons that they shop at independent bookstores rather than going online to buy books. They get that personalized attention.”

For some of the writers who have gone the Opus route, the Politics and Prose name does lend a kind of prestige. “It’s such a valued place for me and my friends and my community, and I love walking into the store and seeing my book on the shelf,” says Jill Morningstar, the author of Eva Schmidt, a novel about a Jewish orphan who becomes a fortuneteller to the wife of Joseph Goebbels.

Morningstar spent her career working on Capitol Hill and at nonprofits like the Children’s Defense Fund. “At some point, I hit a wall and decided I wanted to do something more left-brained,” she says. “With no skills in the visual arts and no theater group willing to take me on, I decided to write a book.” The novel, which Morningstar researched extensively, took a decade to write. But the traditional publishing route didn’t work out. “Publishing houses don’t do much for you anyway unless you’re really at the top of the list of bestsellers. You’re still flying around the country trying to market and sell your book. You still do most of the effort.”

Michael Sodaro, a longtime political-science professor at George Washington University, did have experience with regular publishers, having previously sold books to Cornell University Press and McGraw Hill. But he couldn’t find any takers for Island of Myths, a 600-page historical novel about a Sicilian family that he began writing in 2007. “I don’t know anybody in literary publishing in New York,” Sodaro says. “I didn’t [write it] with the intention of starting a new career as a novelist. This was an obsession, in a way. I enjoyed every minute of it.” Island of Myths was published in 2021, and it scored a coveted review from the industry publication Kirkus, which called it “a mesmerizing novel as historically astute as it is gripping.”

Yet even with that bit of national attention, Sodaro’s book has sold only a handful of copies. No Opus author is getting rich from sales. Even Pat Collins, its biggest success story, says his income from Newsman has been just about enough for him to break even. But not every writer craves stardom, and not every book has to be a blockbuster. Sometimes it’s enough just to have the work finished and printed. “You don’t write these things to put yourself on easy street,” Collins says. “It’s more like a personal therapeutic exercise you go through. It’s good for the soul.”

Opus’s Bestselling Books

Newsman by Pat Collins

A beloved local TV reporter writes about his career, from unsolved murders to measuring winter weather with a “snow stick.”

Words: Connect, Clarify, and Lead by Phyllis Mindell

The late self-help author, who also wrote How to Say It, for Women, penned this guide to effective communication.

Breaking Into Light by Laura Martin

A volume of poetry intended as a balm for different kinds of loss.

Redesigning the University by Timothy S. Tracy, Richard J. Messina, and Serena K. Matsunaga

A handbook for university trustees.

Riding the Rails by Harvey Sloane

The memoirs of a former Louisville mayor who later served as DC’s public-health commissioner.

This article appears in the August 2025 issue of Washingtonian.