t the eastern edge of downtown Charlottesville—past the red-brick pedestrian mall with its bookstores and fudge shops and busking guitarists, beyond the incongruously modern amphitheater, just as the road begins to slope downhill toward the train tracks and then out toward Monticello—sits an utterly nondescript condo building.

I was there looking for the site of some highly unusual research conducted within the University of Virginia’s medical school. It’s mind-bending, norm-challenging work that explores the metaphysical—which is why I’d expected something a little more mystical. A spiral staircase, an owl, a crystal ball. The divination tower at Hogwarts. Certainly not a mid-rise straight out of Anywhere, USA. Only there it was, visible through the glass front door: a placard in the lobby reading “Division of Perceptual Studies.”

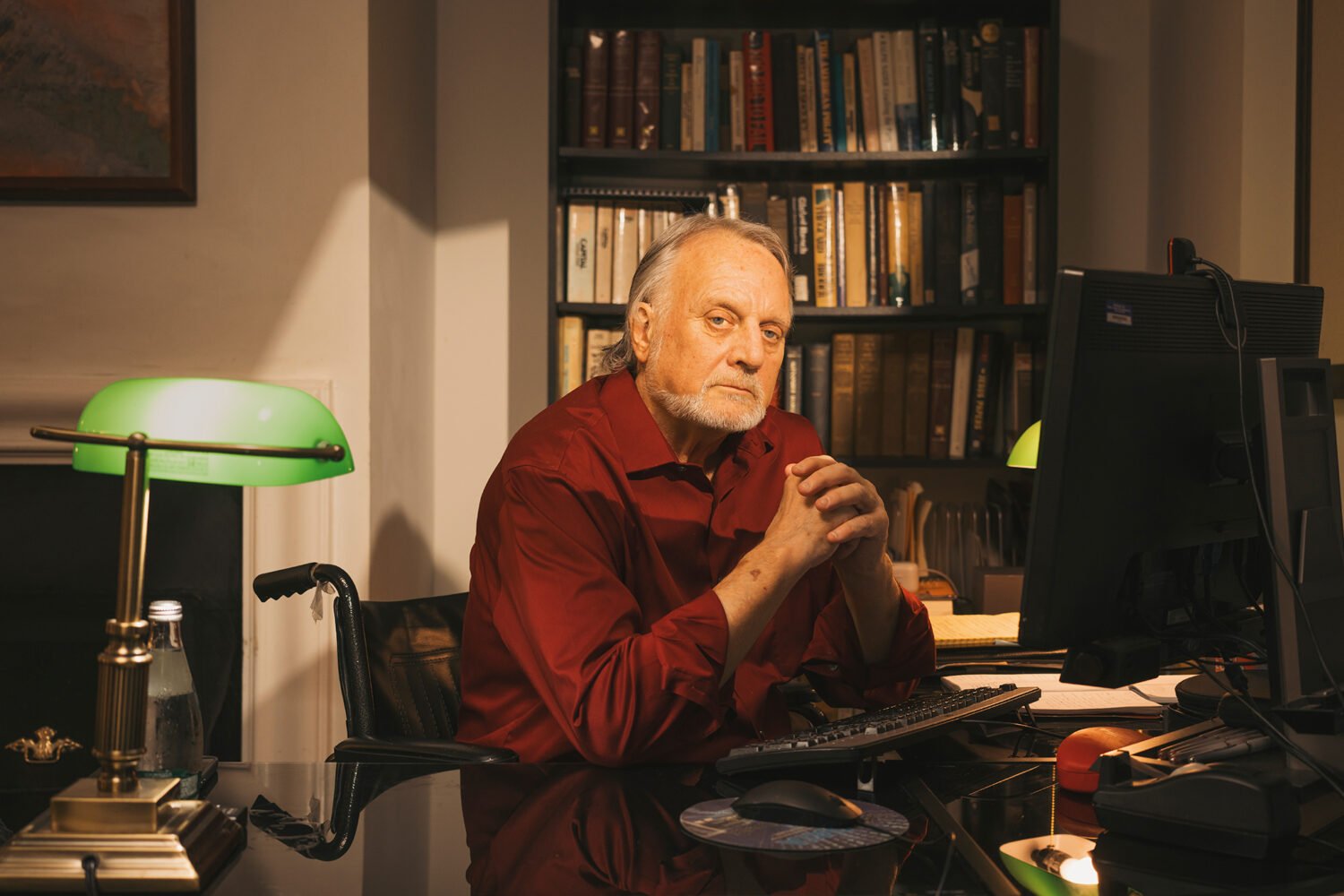

The door handle turned with a wiggle. Upstairs were the researchers I’d come to see, inside an office lined with heaving bookshelves, at wide wooden desks scattered with papers and research journals. They’ve devoted their careers to one of life’s biggest questions: What happens when we die?

The short answer: No one really knows. But the scientists at the Division of Perceptual Studies—DOPS, for short—are doing their best to find out. Founded in 1967, the 14-person group investigates the relationship between life and death, mind and brain, and the tantalizing, albeit woo-woo, possibility that when our physical bodies perish, our consciousness persists.

The only major research unit in the country, and one of a few in the world, specifically devoted to studying the paranormal—or “psi,” in industry-speak—DOPS is not standard academia. A workday for one of the researchers might entail speaking with a child who recalls a past life or fielding an email from someone who’s had a premonition about a looming disaster. Sometimes, it involves walking downstairs to the Faraday cage, a room lined with metal sheeting where researchers conduct experiments related to telepathy and altered states and consciousness. (The cage’s purpose is twofold: It blocks electromagnetic interference so researchers can measure electrical activity in subjects’ brains, and it ensures that subjects can’t cheat, faking telepathy by using wireless communications devices.)

When Marieta Pehlivanova, a psychologist at DOPS, tells parents at her young child’s school about her job, they often pause for a beat and share the same assessment: Interesting. “But I don’t think they mean ‘interesting’ in the usual definition,” Pehlivanova explains. They mean: Hmm, that sounds strange.

Alongside Bruce Greyson, a psychiatrist, Pehlivanova spends much of her time studying near-death experiences. Also known as NDEs, they are relatively self-explanatory, occurring as physical death approaches—when a car strikes a pedestrian or a swimmer is caught in a riptide, when a clogged artery restricts blood flow to the heart. Survivors often recall similar sensations: brilliant light, a feeling of harmony with the universe, a sense of separation from the body, the presence of mystical beings.

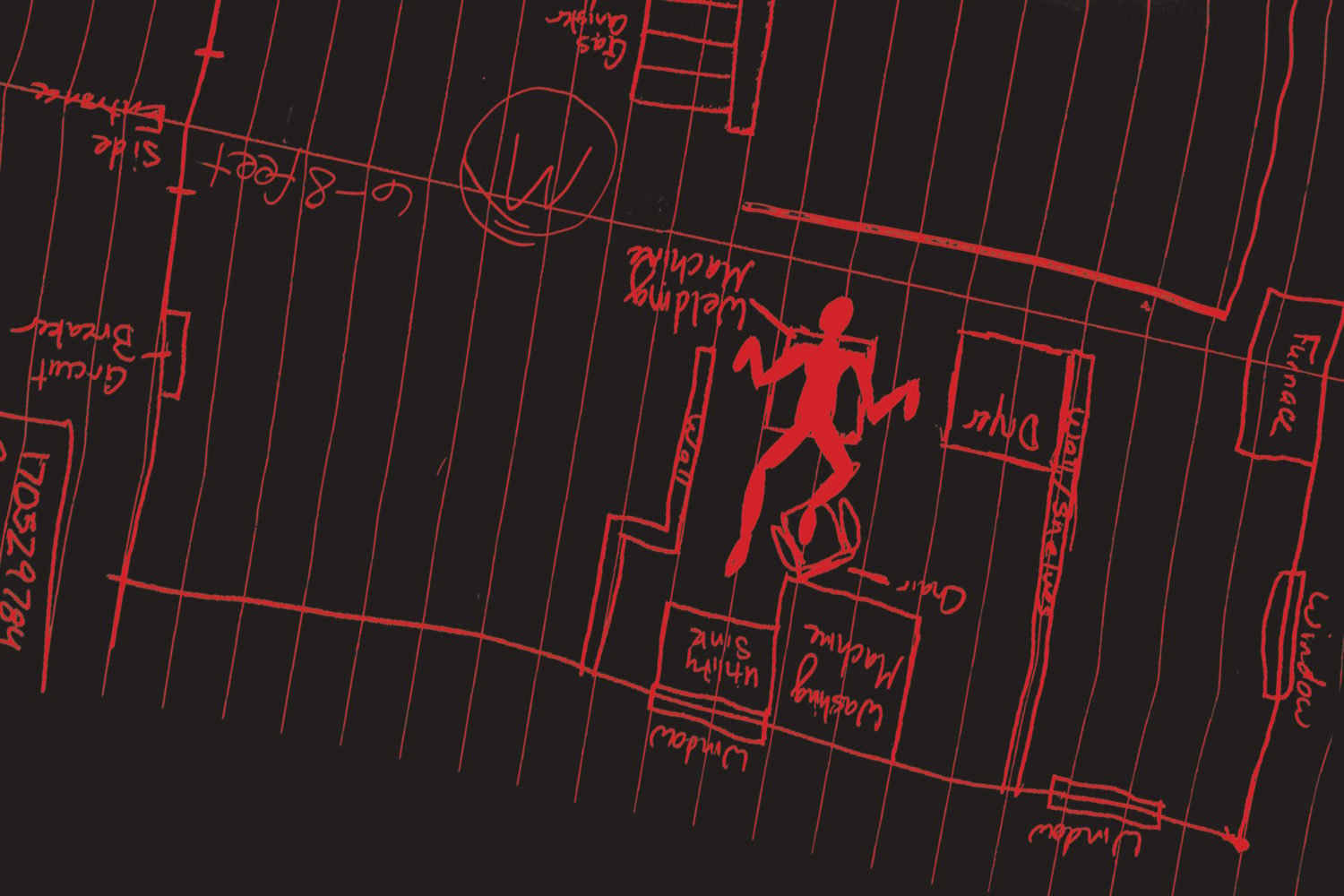

Probing these experiences strains the traditional scientific method. Researchers can’t hook a patient up to a set of electrodes, ask him to almost die, then see if his brain waves had any interesting fluctuations. Instead, Greyson and Pehlivanova rely on recollections. They conduct interview after interview and receive more emails than they can reasonably reply to, all from people bursting with thoughts and questions about their own NDEs.

Much of that collected testimony is typed up and stored in metal file cabinets. The whole scene is more Dunder Mifflin than Harry Potter. But contained in this data, these years of anecdotes, is the heart of the mystery Pehlivanova and Greyson hope to solve. Their job is to look for patterns, publish academic papers, and push for acceptance and respect within the scientific community, where it’s more acceptable to pose questions about cures for cancer than it is to tell the story of a patient who insists she spoke to a celestial being while her body was flatlining on an operating table. NDEs may strain scientific understanding—but that’s exactly why DOPS researchers believe they’re worth serious study. “Scientists don’t run away from things we don’t understand,” Greyson says. “We run towards them, try to understand them.’”

In 1989, Joan Fowler was cycling on the Pacific Coast Highway when she was hit by a truck. The next thing she knew, she says, her consciousness was floating above the scene.

“I could see my bike sort of halfway under the truck and my body to the side . . . and I thought, wow, that’s so fascinating,” recalls Fowler, a reconnective healer who lives in Silver Spring. “And in that moment, while I was watching, I could feel this pull to my right side. And as I allowed my attention to go towards that pull, I could see this beautiful white light. I could feel this warmth and love, and I could feel my physical boundaries just disappear. I became really expansive.”

Fowler’s experience was uncommon, but not as rare as you might imagine. Researchers estimate that some 5 percent of American adults will report having an NDE over the course of their lives; among cardiac patients, that number can jump to about 20 percent. And the phenomenon has a long history. During the first century, Pliny the Elder wrote about a man who’d experienced something that sounds a lot like an NDE. Carl Jung reported having one during a 1944 heart attack, later describing how he’d left his body and observed the world from above. And years after a 1961 NDE during a bout with pneumonia, Elizabeth Taylor told Oprah Winfrey all about it, including a conversation with her deceased husband.

In 1975, Raymond Moody popularized the term “near-death experience” in his book Life After Life, a qualitative survey of 150 people who’d reported NDEs. Initially released by a tiny publishing house in St. Simons Island, Georgia, the book eventually sold more than 13 million copies after a major firm acquired the rights.

Soon after the book was published, Moody began his psychiatry residency at UVA, where Greyson had just finished training. Greyson remained on staff, and he happened to serve as Moody’s supervisor in the emergency room. When he learned about the younger doctor’s research, Greyson felt a tug of familiarity. Over the course of his own residency, Greyson says, he’d encountered patients who reported “these unbelievable stories about leaving their bodies and seeing things going on around them, meeting deceased loved ones and so forth. I assumed they were mentally ill.”

The more Greyson learned about Moody’s work, the more intrigued he became. One day, Moody brought Greyson a massive box of correspondence from people who had read or heard about Life After Life. “ ‘This is this week’s letters,’ ” Greyson recalls Moody telling him. “Every one was from someone who said, ‘You mean I’m not the only one this happened to?’ They had [NDEs] a year ago, ten years ago, 30 years ago, and thought they were the only [person] that it’s ever happened to. They were afraid to tell anyone about it.”

Greyson reached out to DOPS founder Ian Stevenson, who had stepped down as the chairman of UVA’s psychiatry department to study parapsychology—that is, psychic and paranormal phenomena, including his passion, reincarnation. Greyson was curious: Had Stevenson ever looked into near-death experiences? His answer: Sort of. In less than a decade of work, Stevenson had collected dozens of accounts, filed as “deathbed visions” and “apparitions,” which sounded a lot like NDEs.

Greyson and Moody began to add to Stevenson’s collection, hoping to come to some understanding of what, physically, was happening in patients’ brains. “I was still in the materialistic mindset that I was trained in as a college student and then a medical student: The mind is what the brain does, and that’s it,” Greyson says. “I couldn’t make any sense of it.”

Though Greyson collaborated with Stevenson, he wasn’t officially on staff at DOPS, which in those early days operated almost completely out of the public eye. Bankrolled by a $1 million gift from the inventor of the technology behind Xerox machines, the unit evoked curiosity—and skepticism. University leadership hasn’t always been “favorably disposed” to the research, Greyson says, and in those early days he kept one foot firmly planted in the world of traditional medicine.

Pursuing a somewhat conventional path as an academic physician, Greyson left UVA for the University of Michigan and then the University of Connecticut. But in his free time, he kept researching NDEs—even after bigwigs at Michigan told him it would torpedo his future. “Most doctors had no idea what we were talking about,” he says of his work in the ’70s and ’80s. “They thought we were being too gullible. We would present at the American Medical Association conferences and there’d be very polite attention from the audience, but nobody would really say anything.”

Greyson was undeterred, even as parapsychology remained the black sheep of the scientific world. In 1985, the United States National Research Council commissioned a panel that studied paranormal claims, finding that “despite a 130-year record of scientific research . . . [there was] no scientific justification for the existence of phenomena such as extrasensory perception, mental telepathy or ‘mind over matter’ exercises.” Seven years after the panel’s 1988 report, Greyson returned to Charlottesville and joined DOPS. He took over for Stevenson in 2002 and retired in 2014, but he continues to research and write. Today, he’s the face of his field: With his crisp button-down, gray-checked suit and slightly rumpled silver hair, he looks the professorial part. Four years ago, he wrote a book about his research, After, that has sold more than 100,000 copies. Last spring, he was a guest on Oprah’s podcast.

Near-death experiences may strain scientific understanding—but that’s exactly why Greyson and Pehlivanova believe they’re worth serious study: “Scientists don’t run away from things we don’t understand.”

That the public is interested isn’t surprising; a 2023 Pew poll found that 83 percent of Americans believe people have souls or spirits in addition to their physical bodies, and 74 percent believe science doesn’t have an explanation for everything. But skepticism within academia persists. In 2007, Princeton University’s Engineering Anomalies Research Laboratory, which studied telekinesis, closed. DOPS, meanwhile, continues to run entirely on private funding, including donations from the actor John Cleese, and relies heavily on volunteers to support researchers with everything from data analysis to Instagram posts.

For a researcher aspiring to study phenomena like NDEs, the path is anything but straightforward. Pehlivanova, the heir to Greyson’s research, is nearly four decades younger, which means that she grew up with a vocabulary for discussing things like NDEs. She has a long-held interest in psychic phenomena, but while pursuing her psychology doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, she kept that quiet. “It was . . . the kind of academic environment where not even spirituality was something that people talked about, or religion—certainly not psi,” she says.

But then Pehlivanova learned there might be a job opportunity at DOPS. She mentioned the possibility to her adviser, who “pulled up the website, scrolled through it, did not say a single thing, closed it,” says Pehlivanova, who made a silent vow: I’m never mentioning this ever again. Still, her interest persisted. When the position was funded, it was Pehlivanova’s if she wanted it. She didn’t think twice about accepting.

Two years ago, Pehlivanova received an email from Tara White, a chiropractor in Santa Fe. While kayaking on the Rio Chama in New Mexico, White had been swept by wild rapids into a large boulder.

Next, as she later wrote to Pehlivanova, “I saw myself on the rock watching as my body drowned in the rapids below the rock. I watched as my body floated down the river, hitting different rocks, getting beat up.” All the while, White felt warm and content, surrounded by three “beings of light.” She was happy to remain wherever she was “forever. . . . It was so quiet, lovely, and calm.”

But that sensation quickly shifted. White saw police arriving at her house, telling her husband and two children that she’d died on the river. Her sense of calm evaporated. “They cannot have a mother who dies early,” she recalls thinking. “And so the moment that I did that . . . it’s like I was slammed back into my body. And it was cold. And I was underneath the water.”

To evaluate and compare NDEs, Greyson created a scale, a series of 16 questions that get at the commonalities among many NDEs. Did time seem to speed up or slow down? Did scenes from the future come to you? Did you see deceased or religious spirits? Were your senses more vivid than usual? Each response can earn up to two points, and anyone who scores higher than a seven is considered to have had an NDE, with higher scores corresponding to more intense, profound experiences—in DOPS-speak, “deep NDEs.”

Beyond those commonalities, the specifics vary from person to person. One subject told Greyson he’d experienced elements of heaven and hell and that Jesus had ultimately sent him back. Another said he’d had an out-of-body experience while under anesthesia and noticed that a nurse in the operating room wore mismatched shoelaces. People report seeing vivid scenes from their childhood, meeting deities, smelling strong scents. NDEs also seem to vary based on gender, religion, and cultural background. For example, people in the Western world tend to describe being at the end of a long tunnel, whereas people in less developed nations say they were at the bottom of a well. Once, a trucker told Greyson he’d been sucked into a long tailpipe.

That said, some people also report experiences that conflict with their cultural and religious expectations of death. For example, a Christian might describe a scene more in line with Buddhist teachings. In a 2013 paper, Greyson used that phenomenon to upend the critique that NDEs might be a result of imagination, of subconscious suggestion. I’ve read about near-death experiences, and they usually involve lights and tunnels. Or: My religion believes in heaven, so when I worried I was about to die, I saw angels. Also, Greyson wrote, “experiences that were reported before 1975, when Moody’s first book coined the term NDE and made it a well-known phenomenon, do not differ from those that were reported since that date.”

So what, exactly, causes NDEs? Greyson and Pehlivanova can’t say for certain. Some scientists believe there’s a physical explanation, some mechanism rooted in the brain or body that places them in the same category as hallucinations. If that’s the case, then NDEs could be written off as a quirk of biochemistry—and not a possible window into consciousness existing after death.

Greyson and Pehlivanova have looked at more than a dozen such theories. All, they say, have been disproven, and they illustrate how difficult NDEs are to study. For example: Anyone who comes close to death receives insufficient oxygen for a period of time. Could that trigger hallucinations? Greyson looked at data from hospitalized cardiac-arrest patients and found that those who reported NDEs had greater oxygen levels than those who didn’t. Similarly, researchers have found that hospital patients taking higher doses of drugs report fewer NDEs than those taking lower doses.

Near-death researchers can’t hook patient up to electrodes, ask him to almost die, then see if their brain waves had any interesting fluctuations. Instead, they rely on recollections, interviews that are typed and stored.

Another theory posits that sudden bursts of electrical activity in the brain prior to death might be responsible for NDEs. However, experiments that involve humans almost dying are a nonstarter, so much of the existing research in this realm has involved studying rats. “No one interviews the rats to see what they were thinking,” Greyson says.

University of Kentucky neurologist Kevin Nelson became fascinated with NDEs early in his career, when a patient described watching a battle for his soul between Jesus and the devil. In 2006, he coauthored a paper that introduced another possible physical explanation for NDEs: REM intrusion, a state in which the brain blends wakefulness with sleep. Nelson and Greyson have since sparred over the REM-intrusion theory—respectfully and academically—and Nelson can’t get onboard with the belief that consciousness exists beyond the human brain. “We don’t have certainly a shred of even the most ordinary scientific evidence for this extraordinary claim,” he says.

Despite their differences, the two doctors agree on one thing: For those who survive them, NDEs can have a profound psychological impact. As Pehlivanova puts it, “This changes people.”

At first, White’s experience on the Rio Chama left her rattled. But over time, it made her question how she approached life. A high achiever, she’d been the valedictorian of her high-school class, gotten a full ride to college, and built a chiropractic practice on her own.

In the wake of her NDE, White felt like none of that mattered. She shut down her practice to spend more time with her kids. “I was having a real challenge being back in my life,” she says. “I felt like I had just stepped off the mental deep end, like I was floating, like I couldn’t be really grounded in 3D life.”

People who have near-death experiences often “report that they are no longer afraid of dying. Even those who have unpleasant experiences say, ‘I know this is not the end, and I’m looking forward to whatever comes next.’ ”

Greyson has spoken with many people whose NDEs were transformative. There’s the manual laborer who lost his violent streak. The TV producer who suddenly felt her job was devoid of meaning. The teenage boy who found a calling as an EMT. “They almost always come back saying, ‘I am much more spiritual now than I was before,’ ” Greyson says. “People will feel connected to everything around them, like they’re part of something greater than themselves. They also report that they are no longer afraid of dying. Even those who have unpleasant experiences say, ‘I know this is not the end, and I’m looking forward to whatever comes next.’ ”

In the early 1980s, Greyson worked with many suicidal patients who had stopped short of ending their lives because they feared what would happen afterward. He worried that NDEs would make these patients more likely to follow through with suicide—but found the opposite. “They said things like, ‘Now I realize I’m greater than just this bag of skin, and the problems that I have are no longer as important as they were,’ ” Greyson says.

In addition to altering worldviews, NDEs can leave survivors feeling perplexed—and alone. Following her cycling accident, Fowler, the reconnective healer from Silver Spring, didn’t know what to make of her NDE, or whom to confide in. When she left the hospital, she told her family about it. They wondered if she had sustained a brain injury. Fowler was then called up for duty during Operation Desert Storm. “I definitely couldn’t talk about it in the context of the military,” she says. “They have a straitjacket for that.”

Historically, near-death experiencers report “a lot of bad reactions, like being told they’re crazy, being told to shut up” when they share what they’ve gone through, Pehlivanova says. Some have been given drugs and put in psychiatric wards, suffering ongoing mental-health issues.

White reached out to Pehlivanova and DOPS because she felt psychologically stuck. “Regular therapy,” she says, “was not getting it done for me.” Learning that what she went through had a name—and that others had gone through similar experiences and changes—helped her become more comfortable with the life choices she had made since her accident.

“That there is anybody studying it at all immediately gave me validity,” White says. “I was like, ‘Oh, wait a minute, this is really a thing. I don’t have to be so hard on myself.’ ”

Greyson and Pehlivanova like to imagine a world in which people like White and Fowler feel comfortable confiding in their doctors—and the psychological impacts of NDEs are taken seriously in post-trauma medical care. To make that happen, DOPS is working to build relationships with UVA’s physicians and to give them tools to discuss NDEs. Recently, the unit sent a questionnaire to more than 200 doctors at the school. “Almost all of them knew at least something about near-death experiences,” Greyson says. “Most of them thought they should talk to patients about it. Most of them thought they didn’t know enough to do so.

“You really need to be open to hearing what the patients want to say about it—not telling the patient what happened to them,” he adds. “If they want to think that it’s a lack of oxygen, or a gift from God, or psychological fear of death, let them come to their own conclusions. But listen to what they say about it, and how they think it’s going to affect their future life.”

Years ago, one of Greyson’s interview subjects shared an odd detail: While floating above his own body during surgery, he could see his surgeon make a flapping motion with his arms.

Puzzled, Greyson sought out the surgeon, who immediately understood the movement he’d described. After he scrubbed in and put on sterile gloves, the surgeon explained, he didn’t want to risk touching anything that might have been a contaminant. So he placed his hands on his chest and directed his team by pointing his elbows at various items in the room.

The practice of fact-checking accounts is common at DOPS, not out of skepticism but as a means of validation. The arm-flapping surgeon is at the core of what the unit wants others to recognize: experiences that defy understanding. The “reductionist physiological theories that claim to explain NDEs by explaining—claiming to explain—one aspect of them,” Pehlivanova says, have little mechanism to account for how an anesthetized patient could have observed his doctor waving his elbows here and there as the operation got underway.

A 2023 Pew poll found that 83 percent of Americans believe people have souls or spirits in addition to their physical bodies, while 74 percent believe there are some things science can’t possibly explain.

What happens when we die? Are we more than our bodies? Nelson, the University of Kentucky researcher, mirrors the medical and scientific consensus when he says that “consciousness is brain-dependent, and I hold to that until proven otherwise.” (Nelson also hopes he’s wrong.) Greyson started in the same place—believing that the mind is nothing more than the physical brain—but has since moved away from such certainty. There are too many inexplicable stories filed away, too many experiences that suggest something more. “It’ll probably take us another 100 years or more to find out what’s really going on,” he says. “I won’t be around to hear that, but I think we are getting there.”

This article appears in the August 2025 issue of Washingtonian.