On a bright September afternoon, a small cluster of people held up anti-Trump signs near the Van Ness Metro, as they have each Thursday afternoon since the spring. Every few seconds, a driver on Connecticut Avenue blared a horn to show support. Peggy McNutt, sitting on a rollator and brandishing a sign that said “No Trump Fascist Regime,” told me she’d taken part in anti–Vietnam War protests, gay-rights marches, and pro-choice events since moving to DC in 1958. But none felt as urgent as this moment. “People are running scared of what he’ll do to them, their jobs, and their families,” she said.

At 96, McNutt is actually not the most senior activist who regularly takes part in these protests against the administration. She’s not even the oldest in her building, a midcentury co-op tower near the Metro. (That distinction likely goes to 100-year-old Elly Newman, who organized garment workers in the 1940s and joined the March on Washington in 1963.)

Most of the organizers of these Van Ness events have been politically active for years, and many have worked in government. “I’ve lived through World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, and McCarthyism,” said Barbara Green, a participant in her nineties. “I’ve seen a lot of terrible things, and I’ve got to say this is the very worst time that I know of. So it’s a critical period for me.”

Another organizer, Susan Gillespie, is an octogenarian who worked in the Foreign Service and then for the late Maryland senator Paul Sarbanes. “Every single morning when you read the news, you think, ‘How are we going to change this?’ ” she said. “Well, we have to get out.”

One thing these demonstrators share, aside from their anger at the current administration: They’re decidedly past retirement age. If you live in upper Northwest DC, you have almost certainly encountered—and perhaps given an approving honk to—these clusters of elder dissidents. Small gatherings have cropped up around town since Trump took office in January, and they’ve multiplied since the federal takeover of DC.

Stephen Miller took a swipe at the protesters: “These demonstrators that you’ve seen out here… all of these elderly white hippies, they’re not part of the city and never have been,”

On upper 16th Street, protesters put up a sign in the median strip near the Maryland line that read now “Entering Occupied DC.” In front of Temple Sinai on Military Road, local residents banged pots and pans in dissent. A weekly meetup on Connecticut Avenue in Woodley Park attracts a chorus of car beeps. Some are organized under the auspices of the group Indivisible. Others are more impromptu. But most seem to be dominated by people old enough to collect Social Security.

The phenomenon has been so noticeable that White House aide Stephen Miller took a bitter swipe at it during a news conference in Union Station in August. “All these demonstrators that you’ve seen out here in recent days, all of these elderly white hippies, they’re not part of the city and never have been,” Miller said. The gray-haired resisters—most of them longtime residents who are very much a part of the city—seem to be getting under somebody’s skin.

If you spend any time with DC’s older protesters, a question tends to arise: Where is everybody else? Not all of today’s anti-Trump activists are retirees, of course. The evening after Miller made the “elderly white hippies” crack, a young and Black-led crowd gathered at 14th and U streets to protest the takeover to the rhythm of live go-go, for example, and a few weeks later, hundreds of college students across four DC campuses took part in a walkout to protest the occupation. But it’s hard not to notice that when it comes to in person actions, much of the resistance energy is emanating from the city’s older population.

“People over 60 are often retired and often we have time to spare,” Green explained when I asked about this. “We may have money. We may have a whole lifetime of organizing experience. Young people, for the most part, are busy with college, work, career, families.” And, of course, in the social-media age, younger people now tend to express outrage in ways that don’t involve holding signs on the street.

Yet during the first Trump administration, protest often seemed more vigorous, with participants of all ages offering highly visible pushback. It’s millennials who are often credited with driving the initial stages of the resistance during Trump’s previous term. In DC at least, that no longer seems to be the case.

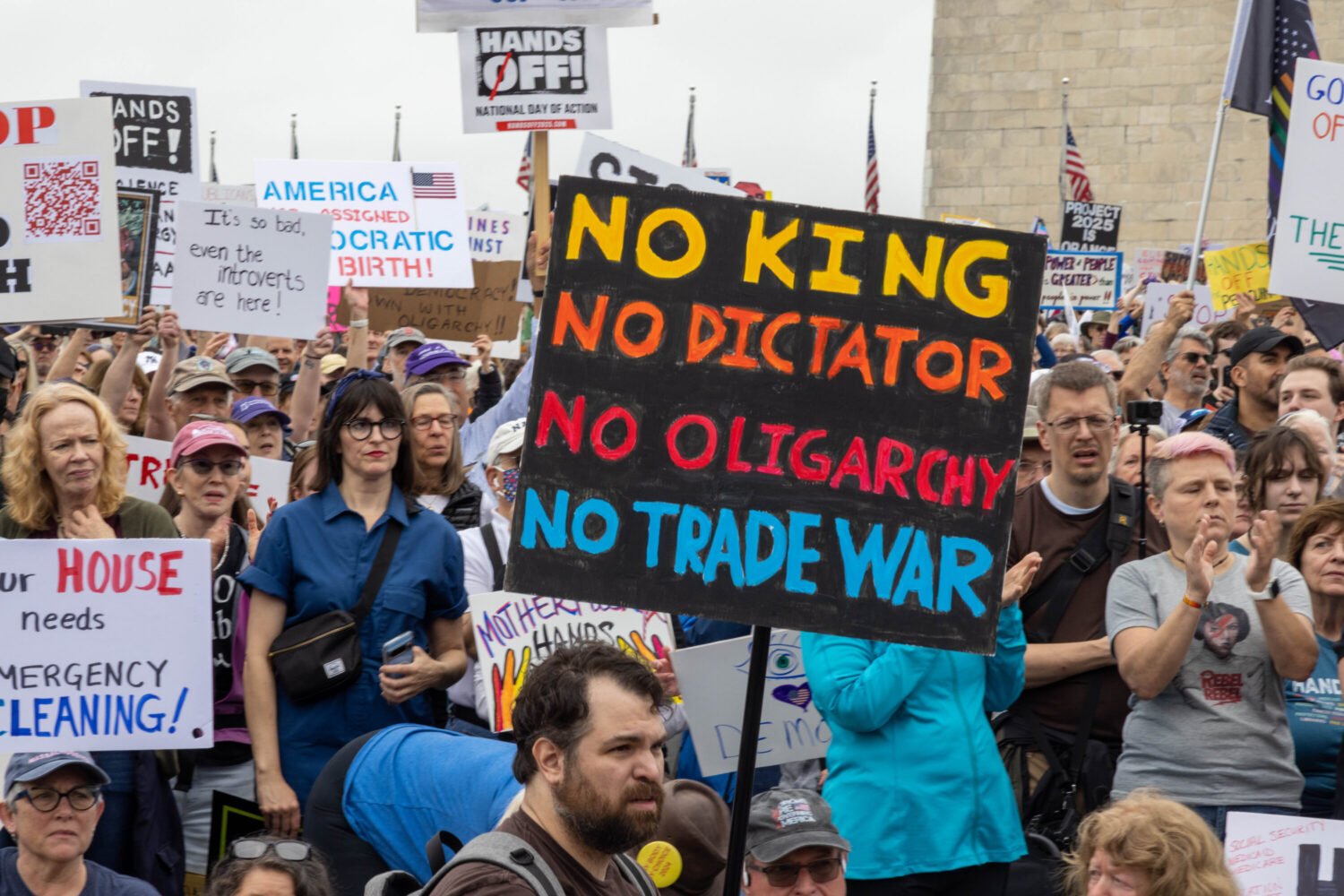

American University sociologist Dana R. Fisher, who studies activism and often surveys protest participants with her team, determined that although DC’s median age is around 35, at the “Hands Off!” rally in April, the median age of a randomly selected group was 51. It was the oldest crowd at any protest Fisher had ever surveyed.

So what’s going on? Older demonstrators are “out there because they remember when this kind of mass mobilization worked,” Fisher says. “Peaceful resistance was a mainstay of their youth.” In general, she says, the current crop of protesters against authoritarianism have been whiter, older, and more educated than their equivalent in Trump’s first term. On the other hand, actions specifically targeted at the war in Gaza and the federal occupation of cities like DC and LA have been younger and more diverse.

Michael Kazin, a historian of American social movements at Georgetown University, told me he could think of only one successful protest effort of the past century led by people of retirement age: the movement supporting the Townsend Plan, an old-age pension proposal by a California physician during the Great Depression that paved the way for the Social Security Act. But Kazin also thinks it makes sense that somebody who came of age in the 1960s would feel called to keep protesting Trump. “For people my age,” the 77-year-old Kazin says, “it almost seems like a moral stand to take to put your body on the line. You want to show your face, you want to stand up and be counted.”’

And Fisher believes a certain amount of dejection has set in among the younger population. “There’s no reason why they wouldn’t expect to see authoritarianism winning,” she says. “Because it’s won more than it’s lost during the period that they’ve been adults. The Hands Off, the No Kings days, they’re still very much about fixing the political system that we currently have. The thing is, if you look at data, young people no longer have confidence that this two-party political system works.”

At a recent demonstration on the National Mall, Dave Gemmell sported a pointed sign on his mountain bike. “Stupid White Hippies,” read the message scrawled on a piece of poster board, a sarcastic repurposing of Stephen Miller’s jab. Gemmell, a 68-year-old in a bike helmet and sporty sunglasses who had pedaled down from his home in Silver Spring, cheered as Senator Chris Van Hollen addressed a few hundred people.

The crowd was made up disproportionately—though by no means only—of people in the retirement demo. “I had a moment maybe four months ago,” Gemmell said, “when I went to a protest and I looked around and everybody was white and they were old.” A retired pastor, he’s used to spending time with a more diverse group. “I’m thinking, why aren’t the rest of my folks here? And I began figuring it out: No one wants to get disappeared. No one wants to get arrested. No one wants to get thrown in jail.” Being old and white, he said, gives him and some of his fellow demonstrators an “undeserved” ticket to safety. It’s the least he can do to show up for those who have more to fear.

A few yards away in the shade sat Debbie Harr, a retired speech-language pathologist from Wichita, who had just walked to the Mall from Maryland for the event. Like several of the protesters I spoke to for this story, Harr said she wanted a message of alarm to get across. Sometimes it felt as if other generations didn’t understand the stakes. “The younger people, even if they’ve heard stuff in school about history, I don’t think they appreciate what they have [with American democracy],” Harr said. “And it’s slipping away.”

That’s also true of members of the informal gray resistance, many of whom took part in actions that helped bring about some of the most sweeping social changes of the 20th century. They remain committed to protest precisely because they witnessed its material results firsthand at a formative age. What’s unclear is what form the opposition to Trump—and subsequent authoritarian efforts after he leaves office—might take once they’re gone.

Back at the Van Ness protest, the cluster of regulars were still holding their hand-lettered antiauthoritarian signs aloft. They’d been at it nearly an hour now, and while the response from passersby could be invigorating, the whole thing started to feel a bit monotonous and routine. Of course, I was just observing—my role as a reporter prevented me from joining in.

Not that the participants didn’t try to get me to. At one point, one of them offered to hand me a sign and pull me into the action. It didn’t escape their notice that I was born decades later than anyone else out there that afternoon. McNutt smiled darkly at me. “You’re our token young person,” she said. “It’s good to see a young face out here.”

This article appears in the November 2025 issue of Washingtonian.