The most remarkable thing about Geoff Tracy’s restaurants is

how unremarkable they are.

There’s nothing in the room or on the plate at any of his four

places in DC, Maryland, and Virginia to make you stop and take notice. No

nods to prevailing fashion, no gestures toward the latest trends and

concepts. And that’s precisely as Tracy has scripted it. At a time when

the restaurant scene has exploded but a great meal out is an uncertain

bet, his places trade on the comfort of the familiar and simple thing done

well.

You’re unlikely to remember your meal two weeks later. Heck,

you might not even remember it two hours later.

None of which is put forth as criticism.

Tracy himself would be the first to point out that his

restaurants are successful not because he’s a creative mastermind. His

mission statement is writ large on his awnings and menus: “Great food,

libation, merriment.” The phrase dates to 2000, the year he opened the

first of three Chef Geoff’s. The message: No aspect of the dining

experience should stand above the others; all three are equal. It’s a far

more populist sensibility than you might expect from a restaurant with the

word “chef” in the title. That’s Tracy.

One of the greatest compliments you can pay him is to tell him

you loved your recent dinner at one of his restaurants but you can’t

recall what you ate, who served you, or even, come to think of it, where

you dined. Consistency and seamlessness of experience are the enduring

virtues of Tracy’s restaurants, the reason he has managed, in a little

more than a decade, to build a company on its way to becoming a small

empire.

Like most successful restaurateurs, Tracy credits two decades

of experience, endless hard work, and a commitment to improving that

borders on obsession. But unlike most restaurateurs, Tracy places his

faith in a highly unorthodox system that confounds many of his brethren in

the business, a system that invites comparisons with the corporate tech

world in its devotion to data collection and with baseball’s current crop

of Moneyball GMs in its reliance on metrics and efficiencies. You’ve read

about artist chefs, businessmen chefs, and even CEO chefs. Meet the chef

as engineer.

Six-fifteen PM, Chef Geoff’s in Upper Northwest DC: You slip

into a corner booth. Elizabeth, the server, is agreeable in her smart tie

and pressed apron, the Pinot Gris is crisp and cool, the salmon with

lentils is perfectly cooked, the water glasses are kept filled, the check

comes without asking. Were you dining at one of Tracy’s spinoffs—Chef

Geoff’s in downtown DC or Tysons Corner, or even at the Italian-themed

Lia’s in Chevy Chase—your night wouldn’t be appreciably different.

Missteps in a Tracy restaurant are few. Things unspool

smoothly.

Here comes Tracy from the kitchen now, making the rounds, ball

cap cocked back on his head, his blue eyes gleaming. This is the public

face of his restaurants, the fun-loving guy down the block who opens his

home to the neighborhood for a nightly party.

It’s not at all a front, but as in his restaurants, what

matters most is what you can’t see. Compared with the level of detail with

which Tracy and his team watch your night unfold, you’re looking at a

black-and-white Philco and they’re staring at a high-def

flat-screen.

Did Elizabeth bring your Pinot Gris within three minutes of the

time you ordered it? Were your appetizers delivered within seven minutes,

entrées within ten, desserts within seven? Were these plates described at

the table before they were set in front of you? Were napkins refolded when

you went to the restroom? Was non-bottled water referred to as “ice water”

(correct) or “water” (incorrect)?

That couple sitting across from you picking at a plate of

hummus might be catching a light bite before a movie, or they might be

working secretly for Tracy. Once a month, he brings in anonymous reviewers

from an agency in New York to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of each

of his restaurants. One recent assessment noted ten small errors: A

dessert recommendation was offered only when the customer asked, and the

plate took ten minutes to arrive instead of seven; the sink in the women’s

room needed cleaning; bottled water wasn’t offered. Still, the restaurant

scored 93 out of 100 points.

When Tracy is in the kitchen he, too, is gathering data,

snapping photos of the tuna tartare appetizer on his iPhone to share with

managers at his other locations to make sure the plating is consistent,

the baked-wonton garnish jutting upright the way he wants. From the

kitchen at Tysons, his roving director of food and beverage, Wil Going, is

performing the same quality control, shooting pics of the shrimp and

grits, the bestselling item on Chef Geoff’s menu, and the mushroom

ravioli, the most profitable.

On this night, a member of Tracy’s team is finishing up her

exhaustive, bimonthly sweep of the original Chef Geoff’s on New Mexico

Avenue, Northwest, assessing the staff’s performance on 800 “standards”

that break down the daily business of a restaurant into discrete

measurements. Are all items chilled to 70 degrees before being placed in

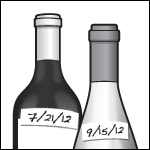

the walk-in refrigerator? Are wines by the glass dated to ensure

freshness, and are they less than two days old? Is the dishwasher’s final

rinse set at the proper temperature?

Tracy’s team converts this information to numbers, which are

then crunched to compile weekly reports and later monthly and a quarterly

report cards.

All this orchestrated oversight to keep a low-key neighborhood

restaurant—a place that sits several rungs below the pampered refinements

of Citronelle or CityZen—running smoothly?

“Consistency,” Tracy says, “is a lot harder than it looks. It

might just be the hardest thing of all to achieve.”

When members of Tracy’s management team talk about their time

in the business, they speak of two distinct periods: before Tracy and

after Tracy.

These are industry veterans who have worked for some of the

biggest names in Washington, yet listening to them compare their

experiences, you might think they had come not just from different

companies but from different industries.

“When I came to work for Geoff, I thought I knew how to do my

job,” says one. “But then I came here and learned I could do it

differently and better. And I grew.”

“Does it sound like we’re all drinking the Kool-Aid?” another

asks, laughing. “Well, we are. There’s a lot to drink.”

To go to work in one of Tracy’s restaurants is to join one of

the most organized, forward-thinking, technologically advanced operations

in the local industry.

Most restaurants train employees for two weeks. At Tracy’s

restaurants, education is constant. Every dish at every restaurant—more

than 1,685 items—is digitized, with links to recipes and information for

servers. There are custom-made training videos on everything from how to

tourné a potato to how to enter an invoice. The emphasis on doing things

precisely is one reason you’ll never hear a server say, “Are you finished

with that?” The gracious “May I clear the plate?” is drilled into all

waiters.

Tracy finished first in his class at the Culinary Institute of

America—after graduating from Georgetown—but half of his cooks have no

formal training. Most staffers on the floor have either limited experience

or came from systems antithetical to Tracy’s.

Tracy’s team has broken down his operation into 70 training

courses—from cost control to “Wines of Italy”—along with comprehensive

tests and rigorous study sessions for those tests. Anyone scoring more

than 90 and in the top three in their class earns a $500

bonus.

“Empire” sounds like a grandiose word for a guy as unassuming

as Tracy, but he says volume has always been a core component of his

vision.

Until very recently, that meant the size of his restaurants and

not the number. He’s eager to see whether his ideas, his system, will

translate to a bigger operation. Next month, he opens a Chef Geoff’s in

Rockville. There are plans to add another five restaurants by 2020, a

number that would bring him close to that of the Clyde’s Restaurant Group,

which currently owns 14. The idea of becoming a recognizable local brand

drives him. But for the head of a small company with no investors, it also

brings moments of despair.

Expansion has already made it harder to adhere to his original

vision of high-volume restaurants with the sort of details in the dining

room (white tablecloths, servers in ties) and on the plate (high-quality

ingredients, a globally inspired menu) associated with fine-dining places

while pricing himself competitively with the likes of

Applebee’s.

With a single restaurant, it was possible not only to run the

kitchen but also to make the rounds of the dining room, checking up on

servers, offering diners the personal touch that distinguished his

restaurants from the corporate chains. Friends and coworkers still laugh

at stories of Tracy in the early years, watering the garden at midnight

after a 15-hour day in the kitchen.

Two restaurants—he opened the downtown one in 2002—meant

shuttling back and forth constantly. Three, which he undertook in 2006,

nearly broke him.

The fact that number four, Tysons in 2009, went relatively

smoothly does nothing to assuage his unease about number five.

Not that you’d see it under the cover of his dude-on-the-patio

smile.

Tracy, 39, didn’t burn to be a chef. He didn’t burn to be

anything at all.

He was a Boy Scout growing up in Hartford, Connecticut, three

blocks from a golf course. Rebellion amounted to sneaking onto the course

at night to practice putting and guzzle beer. He excelled at boarding

school and had an array of interests but lacked a focused passion. At

Georgetown, he majored in theology and spent his time pondering the nature

of happiness, inspired to contemplation by Professor Joseph Murphy’s

course “The Problem of God.”

Turns out Tracy could give a practical seminar on the subject

of happiness.

“I’m incredibly lucky,” he says. “I won’t ever say that I’m

not.”

He married his college sweetheart, Norah O’Donnell, now chief

White House correspondent for CBS News. They met his freshman year.

Catching sight of her and her roommate in line one day at the cafeteria,

he and a buddy from boarding school spent several minutes in anxious

consultation, wondering what their “angle” was going to be.

No angle necessary. The angle was niceness.

Tracy and O’Donnell have been together more or less ever

since—21 years now. It is, by all accounts, a storybook life.

They have three adorable kids and a seven-bedroom, nine-bath

Colonial in DC’s Wesley Heights, near American University. They bought it

for $3.2 million in 2010, the same year they published Baby Love:

Healthy, Easy, Delicious Meals for Your Baby and Toddler, a

bestselling cookbook. If he wanted to, Tracy could walk every day through

tree-canopied streets to work—his small suite of offices is upstairs from

the Chef Geoff’s on New Mexico Avenue.

The couple has been spotted working out at the gym together,

holding hands between sit-ups. Many nights, Tracy can be found not in one

of his kitchens but by O’Donnell’s side at a prestigious gala or dinner

party. One of Washington’s A-list couples, the duo is in high demand from

September to May.

Tracy confesses to frequent pinch-me sessions: “Have I gamed

the system? Are you supposed to be having this much fun? And making money

doing it? I’ve got great, healthy kids and a phenomenal wife who’s

exciting to me. Because of her, I get to hang out with the President of

the United States, or the Vice President. And doing charitable events. And

getting recognized in grocery stores. As a kid, I dreamed about being

shortstop for the Red Sox, but you know? This is up there.”

Many of his fellow chefs struggle with the guilt of rarely

seeing their children—sometimes naming their restaurants after them to

compensate—but there’s none of that tortured tone in the way Tracy talks

about his kids. He’s not not-around; he’s there. He’s

involved.

“I’m envious of him,” O’Donnell says. “Geoff is a good manager

at work, and he’s also a great manager of his time—managing his daily

schedule to work out every day the way he does, and work hard and run the

restaurants and be with the kids.”

A nanny and an au pair help, but so does Tracy’s willingness to

take time off. Among the many benefits of having an efficient,

high-functioning system is that it enables him not to have to be around

all the time. Tracy takes frequent advantage, recharging at a “destination

club” owned by former AOL chair Steve Case, called Exclusive Resorts. The

club’s initiation fee is $170,000 and permits executives to rent

properties for $1,000 a day in places such as Vail, Colorado, and Los

Cabos, Mexico. Tracy used all 30 days of his membership last year and

recently signed up for the company’s new, cheaper offshoot, Portico, to

increase his options.

In upper Northwest DC, he’s something of a folk hero for a

recent stunt that landed him in the gossip columns. A newly installed

speed camera nailed his Lexus three times in three days for exceeding the

posted limit. In all, 11,000 tickets and 20,000 warnings were issued to

drivers in the first two months the camera went up. “All y’all that live

in upper Northwest DC and drive on Foxhall Road . . . watch out for the

new speed camera,” Tracy wrote in an e-mail blast to his customers. “It’s

on a downhill so it gets you every time.” He wrote checks for $425, then

hired a guy for $1,200 to stand on Foxhall Road with a sign alerting

motorists to the trap. The back of it read: HAPPY HOUR AT CHEF

GEOFF’S.

Does it trouble Tracy that he gets written about mainly for

being his wife’s date at high-profile functions and for his efforts to

help his fellow citizens avoid tickets?

He laughs.

Or the fact that none of his restaurants has ever made a

Washingtonian 100 Very Best or Cheap Eats list?

“Yeah, what’s up with that?” he asks. More

laughter.

To make either of those lists, he knows, would require

ratcheting up the level of sophistication on the plate and in the room or,

alternatively, scaling back to deliver the sorts of values mom-and-pop and

ethnic restaurants do.

“I know what I am, and I know what kind of restaurants I want,”

he says. “I’ve never wavered on that.”

In other words, he minds the middle. And he minds it as few in

this city ever have.

“I’d be lying if I said I expected any of this,” Tracy says,

eating a crabcake lunch at Chef Geoff’s Downtown. “I honestly never

dreamed there’d be more than the one restaurant.”

This aw-shucks aspect is one of the things that make Tracy so

likable. He’s a bracing palate cleanser compared with the complex stews

offered up by many chefs, with their unchecked egos and unslakable thirst

for attention and validation. Mr. Smith, minus the passion and

ideology.

Tracy arrived in Washington in 1991 without the slightest clue

about what he wanted to do, much less become: “Direction? The last thing I

contemplated was direction.”

It put him out of step with his careerist classmates at

Georgetown, who four years later were bragging about the jobs they’d

landed at companies like Lehman Brothers. “What’s Lehman Brothers?” he

recalls asking.

But Tracy wasn’t without some foundation. He had worked at a

student-run store called Vital Vittles selling Triscuits, ice cream, and

other college necessities, working his way up from stock boy to general

manager of the campus organization that ran the store and other student

enterprises, overseeing a business of 85 employees that made $2 million to

$3 million a year.

In high school, he had bussed tables at the bistro Max on Main

in Hartford, and when a fellow busboy was canned for dealing cocaine,

Tracy went to owner Richard Rosenthal with an offer: “Rich, I can handle

the whole restaurant. You don’t have to hire anyone else.”

Rosenthal was skeptical, but Tracy made good on his

promise.

When Tracy was headed off to college, Rosenthal sat him down

for a talk: “You did really well. You’re gonna go on and become a doctor

or lawyer, and that’s great—you should. Stay the f— out of the

restaurant business.”

“Why?” Tracy asked.

You’re very dedicated, Rosenthal said. You’re nice. The

business will chew you up. It’s harder than you know.

After Georgetown, Tracy and O’Donnell, over the objections of

her Catholic parents, moved into an apartment together in DC’s West End

and began looking for work. On his cap at graduation, he wrote: will work

for food. It turned out to be a case of truth in jest.

Tracy worked his connections to snag a job as host at the Old

Ebbitt Grill—the raw-bar emporium is owned by the Clyde’s Restaurant

Group, whose president, Tom Meyer, is a family friend—then moved on to

Clyde’s in Chevy Chase, where he worked the fry station, manned the grill,

plated desserts. At lunch he waited tables at Cafe Deluxe. It was a grind,

as Rosenthal had said. But more exposure didn’t dim his eagerness. When he

wasn’t working, he was reading cookbooks. He was wowed by what some chefs

could do.

He entered the Culinary Institute of America in 1996. Tracy

quickly learned his limitations, but also his strengths. Other students

could do things at the stove he couldn’t, but he had a gift for seeing the

needs of the entire operation.

When, during a business course, an instructor bewildered a

class by defining a restaurant as “a business open to the public that

serves food and beverage for the sole purpose of making money,” Tracy was

the only one nodding along and not asking, “But what about the chef as

artist?”

“It struck me as profound,” he says.

Halfway through CIA, he served a three-month externship at

Roberto Donna’s Galileo, at the time one of Washington’s top restaurants.

To be the best, Tracy thought, you have to learn from the

best.

Galileo was an education—in what not to do. Purveyors were

strung along with a hundred excuses as to why they weren’t being paid.

Shelves of high-priced food were going to waste. The kitchen was tense,

full of shouting.

I don’t want to run a place like this, Tracy thought. There has

to be another way.

He might never be a great chef, but he knew what he could

do—and in the end, he suspected, that might be more important. He

understood how to lead people, and he understood how to create a

system.

After graduation he worked as floor manager at 1789, also owned

by the Clyde’s group.

One day he approached Meyer. “How many years should I work in

kitchens before I open my own place?” he asked. “Five? Ten?

Fifteen?”

“I usually talk people out of the restaurant business,” Meyer

recalls. “But Geoff just had a passion for it, and he was really smart and

really talented.”

“The time is right now,” Meyer told him. “If you wait 10 to 15

years, you’re gonna have a wife, a mortgage, a dog. What’s your net

worth?”

Tracy wanted to laugh. Or cry. “Fifteen-hundred dollars,” he

said.

Meyer advised him to forget about opening the sort of place

most sous chefs dream of—the intimate bistro where they can express

themselves at the stove: “You’ll be working six nights a week and burned

out in five years.” Instead Meyer urged him to open a bigger, high-volume

restaurant where Tracy could take full advantage of his understanding of

operations.

In the winter of 1999, Tracy agreed to take on the debt of one

of Donna’s satellites, Dolcetto, complete with a freezer of rotting meat

and a rear-wall mural of the chef framed in ivy and flanked by cherubs. It

had just gone out of business.

Three of Tracy’s CIA classmates—including a current executive

chef, David Pow—leapt at the chance to work for him, despite being warned

that they wouldn’t be paid until after the place opened.

Tracy was blessed, also, with an eye for talent. A guy he’d

hired to work the salad station turned out to be an exceptional cook.

Tracy promoted him twice, making him executive chef overseeing the kitchen

at Chef Geoff’s downtown. Great chefs often speak of a grueling

apprenticeship in a Michelin-starred restaurant in Paris followed by

several years of study in a succession of four-star restaurants in the

States. But after only a couple of years under Tracy, a 24-year-old Johnny

Monis struck out on his own and open DC’s acclaimed Komi in

2003.

Tracy’s obsession with systems was born not of the forethought

and planning on which he now prides himself but of necessity. Really, of

desperation.

Lia’s, which opened in 2006, was the first restaurant he

launched that didn’t take over an existing place, a mistake he vows never

to repeat. Build-out costs exceeded estimates, and the job dragged on.

Lia’s struggled in the first few months, and the two Chef Geoff’s were

struggling, too. He worried about keeping all three places afloat. Some

nights, he hardly slept. It was, he says, the worst time of his life, “a

total meltdown.”

He cursed his younger, cockier self as he recalled the words of

his commencement address at the Culinary Institute of America: “When

things become too comfortable, that’s precisely the time to change and do

something else. When your heart’s pumping and you’re really scared, that’s

when you’re really living life.”

His heart was pumping, all right. It had never pumped harder.

Scared? He had never been more scared in his life.

His father, Dan, heard it in their nightly phone conversations.

A retired CPA from Arthur Andersen who gave the books a once-over every

month, he listened to Tracy pour out his frustration and fear one night.

He told his son, “You need to hire your brother.”

My brother? Tracy thought. I should hire a

teacher?

Chris Tracy had worked for Teach for America; had taught

English as a Second Language at DC’s Shaw Middle School at Tenth and U

streets, Northwest; and had just abandoned a PhD program at Johns Hopkins

in sociology. He was uncertain what to do with his life, and while that

meant he’d likely be available, nothing on his résumé suggested he would

be an asset to the company.

But Tracy trusted his father in business matters, and the more

he mulled the idea, the more he thought Chris might be useful.

In September 2006, Geoff brought his brother aboard for what he

figured might be six months, until Chris grew bored or restless. But the

restaurant novice was a quick study, and he liked the work, the

gamesmanship, the idea of competing every day. It was one of the few

things the brothers had in common.

Geoff was a big-picture guy. In college, he had loved the intro

courses, the big ideas, but got bored when he was forced to delve deeper

into a subject. Chris, on the other hand, lived to, as he puts it, “drill

down into the details,” examining the contradictions of things, exploring

their many shades of gray.

Geoff wasn’t so proud that he couldn’t admit that where he was

weak, Chris was strong. Also that where Geoff was weak, the company itself

was weak. He couldn’t keep doing things the old way. He needed a new

system. It would be like starting over again.

Forced to reckon with the kind of restaurateur he wanted to be,

he would forge a new kind of company. Out of the chaos would emerge a new

order.

Chris Tracy sits staring at his two computer screens at 9 am

one morning at company headquarters while Sarah Murphy, the company’s

“executive director of profitability,” feeds him numbers from a sheet of

paper filled with so much data, so minutely recorded, that she has to use

a ruler to make sure she’s read the correct line. By the end of the hour,

he’ll be bleary-eyed. By 2, he still won’t have had lunch.

Downstairs, Geoff makes the rounds of the kitchen—sampling

dishes, snapping pictures, asking after his cooks. He’s performing one

kind of control: a human, tactile interaction. Chris performs another:

detached, numerical.

“We’re both analytical guys, but we’re different analytical

guys,” Geoff says. “I barely understand the things he’s

doing.”

To see Chris preside over a meeting is to see a manner more

classroom than corporate. Lean, dark-haired, and intense, he could hardly

present a more obvious contrast with his brother. His authority derives

less from his need to assert his power than from his willingness to

listen. He doesn’t assert; he asks. He encourages. He challenges. If he’s

reluctant to give the impression of being “top-down” in his management

style, he has no such qualms about being perceived as a wonk. He speaks

excitedly of “data points.” The words “super-actionable, super-precise

data” roll off his tongue.

The numbers Sarah gives him to punch into his spreadsheets

enable him to compile a weekly report for managers at all the restaurants.

The report is a distillation of what he discovers in the surveys completed

by diners on the website OpenTable, along with a graph tracking the trends

at each restaurant (in food, in service) that he distributes to all

managers and an update on the progress they’re making toward their

budgets.

“I don’t think just measuring is what differentiates us,” Chris

says. “What differentiates us is that we share that information with our

managers in a way that is actionable, so that they can drill in and find

out what’s wrong and make intelligent decisions.”

Recent scrutiny of a spike in bar-supply costs at one

restaurant revealed that a manager had been spending too much on mints. A

small cost, perhaps, but it’s minding the little things, Chris suggests,

that distinguishes a successful company from a struggling one.

Later will come monthly, company-wide progress reports—one for

hospitality, one for profitability—and an even more comprehensive

quarterly “report card.”

The report-card numbers are gleaned from three sources. The

work of the New York-based company, Coyle Hospitality Group—hired to visit

each restaurant anonymously every month and assess each aspect of the

dining experience—is converted into hard numbers. The same conversion is

made for the OpenTable surveys. (A diner’s 4, for “very good,” is recorded

as “80%.”) The third set of numbers is taken from the spot checks

performed by members of Tracy’s management team using the 800 standards.

From the 26-page score sheet, it hardly seems possible that Chris might

have overlooked some detail of the restaurant operation.

Chris believes it’s simply not possible to measure too much.

Measurements matter. They improve performance. It’s not a stretch, he

seems to suggest, that if your burger or salmon is cooked right and you

find the staff friendly and attentive, numbers played at least some

role.

The numbers are important in other ways, too. The company’s

incentive program is tied to the stats Sarah Murphy feeds him. Servers who

score a 90 or above from the converted Coyle numbers earn a $250 bonus.

Among the managerial staff, the crucial number—the one they all anxiously

await—is the score on the quarterly report card that measures the rate of

profit relative to the previous year’s quarter. A positive number, and the

managers take home 40 percent of the profit growth; one year, a manager

earned $30,000 for three months’ work.

I spoke to several chefs and managers about the Chef Geoff’s

model—its reliance on data, its elevation of numbers over the “eye test.”

None had heard of anything like it. Some reacted with wry amusement, some

with “hey, whatever works” astonishment.

“Numbers are just tools,” Chris Tracy says when we sit down to

lunch at Chef Geoff’s downtown. “The idea is to get better. To constantly

improve.”

He emphasizes that the numbers grow out of questions, that the

struggle to become more efficient is what propels the data collection, not

the other way around. It’s not, in other words, measurement for

measurement’s sake. Quite the opposite: He’s looking to turn what’s

commonly perceived to be instinctive into something that can be broken

down and quantified.

Chris says they have yet to reach the goals they set several

years ago: a 15-percent profit margin and a score of 95 or higher on the

Hospitality Report Card (a number calculated over the course of the year

and encompassing the scores of all the restaurants). The company ended

last year with a 10.2-percent profit margin and a score of

89.5.

A disappointment, Chris says. One that drives him and the

team.

But there’s no doubt, he adds, that all this number-crunching

is worth it.

In 2001, in its first full year, Chef Geoff’s made just over

$132,000. Last year, the four restaurants earned a profit of just over

$1.1 million. In 2008, the year Coyle began its anonymous visits, the

company-wide score was 80. Last year: 89. The OpenTable surveys have

steadily improved, too, since Chris and his team began tracking them,

rising from 75.3 in the second quarter of last year to 79.5 in the first

quarter of 2012. All four restaurants are profitable, and none carry

debt.

When Rockville opens, the company will have about 70 more

employees to oversee and a 20-percent larger company to manage. It will be

harder than ever for Geoff or Going to visit all the company’s restaurants

in a day, which means it will be harder to maintain daily contact with the

kitchen, to give the constant oversight that helps ensure that dishes are

sent out the same way every time. It means more product to order, more

employees to hire and train, more data to crunch.

And that means trusting as never before in their systems, even

as those systems are being tested as never before.

With Rockville very much on his mind, Chris sits down with

Murphy and Courtney Fitzgerald, the head of hospitality, one recent

morning for a conference call with a software company called iCIMS

headquartered in New Jersey. They huddle around his corner desk. A guy

named Jim is on the other end.

The idea that there exists a single program that might fit all

their number-crunching needs has long haunted Chris’s

thoughts.

“One of my frustrations right now is with our managers’ logs,”

he tells Jim. “There’s a ton of great information that goes into those

logs but not a lot of great analysis.” His managers are doing a good job

of recording pertinent details of their operations. But there’s no easy

way to process that information and make use of it. He concocts a

ridiculous for-instance of the kind of data collection he’s interested in

seeing—a nightly “weather report” from each location.

“Sure,” Jim says with a laugh, “that’d be

possible.”

“And you’re saying you could run reports on the number of

cloudy days?”

“Agreed.”

This pleases Chris, and he looks around the room at the others,

nodding; iCIMS appears more attractive than he anticipated.

Could iCIMS tailor a program to their specific

needs?

It could.

And a different program for each restaurant?

Sure thing.

“What we would do,” Jim says, “is we would have to build those

documents for you. We give you five forms free, and you can go from

there.”

Five forms? To measure everything they need to measure? To

analyze what’s selling on the menus and what’s not? To record the time

between when a dish is ordered and when it arrives, and how long it takes

between appetizer and entrée?

“I’m envisioning about 342 forms,” Chris says.

Jim, hearing hyperbole, laughs.

Chris isn’t laughing.

Geoff breaks into a grin when the conversation is relayed to

him later.

His response underscores an essential difference between the

brothers. What for Chris is a source of frustration is for Geoff one of

those instances in which the seeking is as important as the finding. His

sunniness seems to say: We will find the answer eventually. What’s

important is that they not accept the status quo, that they’re constantly

looking for ways to become more efficient, more consistent.

They sit across from each other in the office, Geoff leaning

back in his T-shirt and ball cap, Chris leaning forward in his crisp,

collared shirt.

Chris is intent on making clear to me that he doesn’t believe

they’ve created a perfect system. They never speak of the structure in

place as if it’s inviolable, complete unto itself—as if they’re content

that they’ve found The Way.

“There is no way,” Chris says. “And that’s the frustrating

thing, obviously. But it’s also the fun of it.”

The fun of it?

“The challenge of it—that’s fun.”

Geoff says, “Figuring it out, like you have to figure out a

game. I think that’s what keeps it interesting.”

“Definitely,” Chris says.

They could be back at their childhood house in Hartford, a

couple of boys bonding over some brotherly interest only they understand.

Rockville looms, and beyond it, five more restaurants over the next eight

years, but they have a yin and a yang to control the chaos.

“I always say,” Geoff says, “if I’m not enjoying it, I’m not

going to keep doing it.”

“Exactly,” Chris agrees.

“It’s work. It’s constant. It never ends. But it’s got to be

fun, too.”

Fun: the 801st standard?

The brothers roar.

Todd Kliman, the magazine’s food and wine editor, is a James

Beard Award-winning food critic and author of “The Wild Vine: A Forgotten

Grape and the Untold Story of American Wine.”