>>Click here for a slideshow of more photos of Red Pearl.

At nearly every Chinese restaurant I visit to review, a moment arises when, having eaten too many dishes in the course of several dinners, I decide to order “off menu.” Sometimes the moment is born of desperation to find something worthy of singling out. But sometimes, as happened recently at the ten-month-old Red Pearl in Columbia, ordering off menu is prompted by a rising sense of excitement that a promising place might be capable of turning out some truly stunning cooking.

It was my third visit in five days, a quiet midweek dinner, and having seen enough evidence to suggest that the kitchen was up to the challenge, I heeded the waiter’s suggestion and had the kitchen cook a lobster from the tank. My dining companion, Dave, a wine writer who lived for a time in China, was well acquainted with such off-menu excursions and eagerly concurred in my selection of a salt-and-pepper preparation.

It was a good thing our wives weren’t with us, and not because we were unmannerly in attacking the plate but because there would have been less for us.

The two-pound-plus lobster had been partially declawed to make for easy eating, dusted with a mixture of cornstarch, salt, and pepper, then dunked into a deep fryer for perhaps half a minute—just enough time to cook the crustacean but not to turn it dry or rubbery. A fine dice of ginger, garlic, and chilies clung to the claws. We not only pried out the sweet, luscious meat; we licked the shells clean, too.

A plate this exceptional wouldn’t have been out of place at Wolfgang Puck’s modish monument to Asian fusion, the Source, though the $39 price tag at Red Pearl probably would have been 50 percent higher at that downtown DC destination.

It’s a measure of just how good Red Pearl is that, although the lobster was the star of the show that night, other dishes played strong supporting roles. There was a tea-smoked duck whose scent turned our heads even before it arrived. The bird is first smoked in a wok, where a slow-burning mound of jasmine turns the meat a deep pink. It’s then roasted to a mahogany brown. The meat, with a thin layer of fat beneath the skin, was as rich and juicy as the best spare ribs. We made sandwiches with the accompanying steamed buns, stuffing them with equal parts meat and skin, which crackled like potato chips.

A rendition of hot pot, kept warm by a Sterno flame underneath, was excellent: small hunks of bone-in lamb, tofu skin, and shiitake mushrooms in a white-pepper-spiced brown sauce with the depth and complexity of a full-bodied red wine.

The lone stir-fry—diced chicken with chilies—was noteworthy for its lack of grease and for the slow, steady burn that’s characteristic of the potent combination called ma la, which brings together chili peppers and the famed Szechuan numbing peppercorn to produce some of the most distinctive spicy dishes on the planet. Ma po tofu evinced the same quality, its jiggly cubes sprinkled with crushed bits of the peppercorn.

It’s not just the menu that tells you this is a Szechuan restaurant—it’s also the smell of cumin that scents the dining room. That resonant whiff led me another night to order several Chengdu specialties.

One—simply called cumin lamb—is an ordinary-looking stir-fry of meat and peppers. But the strips of lamb were tender inside, crunchy outside, and the cumin mingled with the numbing peppercorn and the chilies to produce a fascinating taste—imagine, all at once, the saltiness of potato chips, the spiciness of KFC, the heat of a fiery salsa—that kept me going back for more.

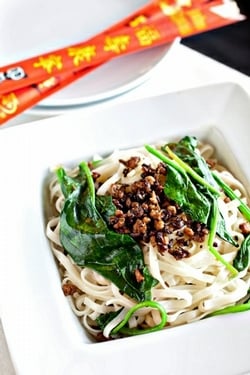

Another is dan-dannoodles, a fixture on the clamorous streets of Chengdu. The noodles here are packaged, not made fresh, but they’re better (thinner, more pliant) than those I’ve encountered in other versions of the dish. A vigorous turn in the red oil at the bottom of the bowl and the noodles are slicked with a smoky sauce that burns even as the noodles soothe.

The other dominant idiom here is Cantonese. A casserole combining lightly fried strips of flounder and tofu with shiitake mushrooms is one of the best expressions of Cantonese cooking in the area. Here again are hits of white pepper in a slightly thickened braising liquid that’s remarkably light and clean.

Some Chinese restaurants upscale themselves with banquet-style presentations and splashy investments in tables, drapes, and other accoutrements—and then charge double what the noodle joint down the street does. Red Pearl’s well-spaced tables are laid with white cloth, the wooden chairs are handsome, the booths are nicely padded. It’s comfortable but not transporting. That’s by design.

Owner/chef David Wong, a Rockville native—his sisters operate Far East in Rockville and Jade Billows in Potomac—has eschewed the trappings of the upscale Chinese restaurant to create a place that, as he puts it, “combines the best of the hole-in-the-wall mom-and-pop that’s all about the food and a place that’s got a nice ambience.” Wong values quiet preparation over pomp. His focus is on leavening the customary heaviness of stir-fries and creating sauces of delicacy and depth. Nowhere is this lightness more evident than in the dim sum offered at dinner. Dim sum is a rich repast, and a pot of tea is an essential part of the experience, both to promote lingering and to help you process a starchy, oily meal. Here no such aid is necessary. The frying is light, the flavors are clear, and the oils are kept to a minimum.

There’s no caravan of carts as there is on weekends, so you don’t see the dishes before choosing, and they cost about double what they do at Saturday or Sunday lunch. On the other hand, the dumplings, buns, and other small plates are all cooked to order. That’s your sign to zero in on anything steamed, such as the fabulous har gow—minced shrimp in a translucent wheat noodle that avoids becoming gummy (a common flaw) because it doesn’t sit on a cart. Char siu bao, or roasted pork buns, come to the table warm, their golden-brown exteriors concealing a wonderfully sweet, sticky braised pork. A plate of eggplant stuffed with shrimp paste was comparable to the best versions I’ve eaten in San Francisco.

I didn’t expect dim sum from the carts to be as good or as consistent, but I did expect it to be better than it was. After a dozen dishes one afternoon, I told my wife I wanted to check the sign out front to make sure we were in the right restaurant. Only a dish of roast pork was memorable. That a kitchen could excel with cooked-to-order dim sum and yet put out such mass-produced dim sum isn’t hard to fathom. But I did expect more. Had my first visit been for dim sum from the carts, I’d never have gone back, never have discovered that lobster.

That’s not to say that Red Pearl at night is a perfect experience. The dining room was perhaps ten degrees chillier than expected. Blame the floor-to-ceiling windows that looked out onto frozen Lake Kittamaqundi. Wong had stationed two heaters in the bar, but they weren’t generating enough heat to warm the rest of the space.

That’s easily correctable. Two other complaints are not, and they go to the heart of what Red Pearl is—and might yet become.

The menu—in particular the back panel listing more than four dozen Cantonese and Szechuan specialties—could use better, fuller explanations of the preparations. Why not give adventurous diners the inducement they need to order such delicacies as braised frog&rsq

uo;s legs?

And though it’s generally true that beer goes better with Chinese food than wine, a number of dishes would be improved by being paired with good wines. A Tsingtao was a clumsy dance partner with the lobster; the dish called for a dry, acidic Chenin Blanc or a sweeter Gewürztraminer. And the tea-smoked duck would have gone beautifully with a spicy Syrah. If Wong is willing to carry Moët & Chandon Champagne for $95, he can afford to carry more than mass-market wines.

Details matter, and Red Pearl has nailed most of them. It’s not a gloss on the takeout joint down the street, nor is it a slick pan-Asian restaurant that ditches tradition in hopes of wooing an upscale audience. It’s a different breed altogether. But to make good on its promise of being one of the handful of Chinese restaurants in the area worth spending a long, leisurely night at, it needs to deliver at every level. That glorious lobster was too good to have been consumed in a chilly room and without a decent wine to match.

This article appears in the March 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.