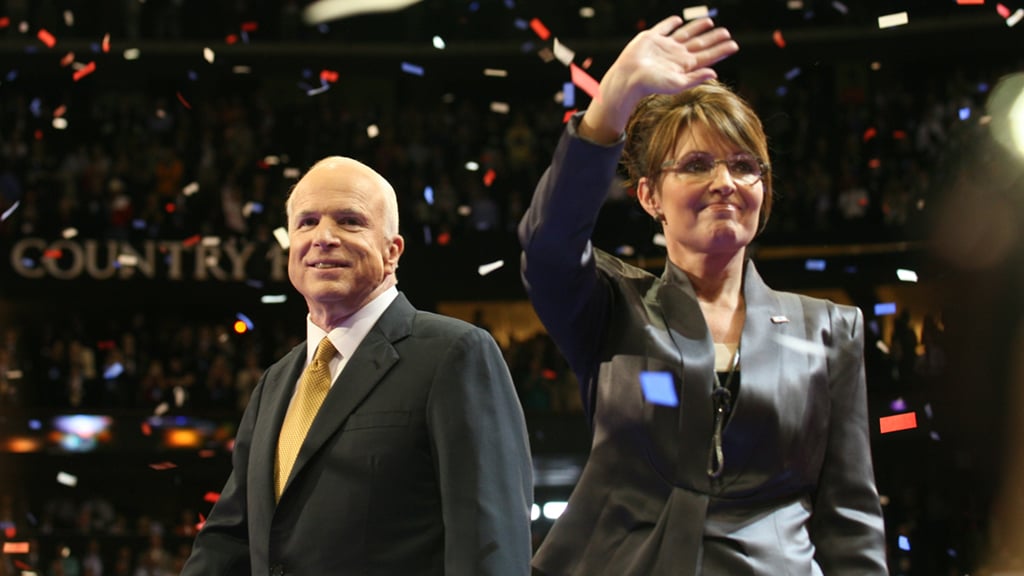

In March 2008, when the nuttier ravings of Reverend Jeremiah Wright, Barack Obama’s Chicago pastor, surfaced—among the reasons God should “damn America,” Wright said, was the government’s supposed invention of HIV “as a means of genocide against people of color”—Obama responded that although he disagreed with some of Wright’s remarks, he wouldn’t toss him under the bus.

“I can no more disown him than I can disown my white grandmother,” the presidential candidate declared.

Journalist Andrew Sullivan blogged: “I would think much, much less of [Obama] if he disowned a spiritual guide because of that man’s explicable if inexcusable resort to paranoia.” Sullivan added later: “I do not believe his refusal to disown Wright is a function of politics, but a function of human loyalty and love.”

We aren’t used to displays of loyalty in politics, and especially rare is when it’s exhibited by a leader. Followers are expected to fall on their swords for the boss, not the other way around. Thus the kudos that first greeted Obama’s assertion of unbreakable fidelity to his old friend and mentor. What a different sort of politician! How refreshing! But it didn’t last long. Soon Wright was at the National Press Club playing to the cameras and needling his prominent parishioner. Sullivan was done praising the virtues of loyalty and instead urged Obama to “irrevocably disown him and say in words that are clear and bright that Wright is now anathema.”

But what made Wright anathema? Was it his race-baiting remarks? Hardly. If anything, at the press club the old minister toned down the rhetoric. No, Wright’s new and unforgivable offense was his disloyalty to Obama—who had, days before, secretly met with the pastor to beg him not to put on a media circus. Wright went on with the show. He declared that his preaching had been within the tradition of the black church, which embraced “radical change” and the social transformation promised by “liberation theology.”

In other words, Wright proclaimed that his was a gospel of left-wing, race-based politics. This just as Obama was casting himself as a candidate of the political middle, a man who would transcend the old politics of race. Obama made his gesture of loyalty to Wright, and the pastor responded by kneecapping his protégé.

So the candidate finally disowned Jeremiah Wright. “He scarcely hesitated to cut his former friend loose,” wrote campaign biographer Richard Wolffe. And by doing that, Obama proved he was “cold-blooded enough to win.”

Next: The perils of mixing friends with politics

Leaders have responsibilities that may override personal loyalties. Subordinate your political life to your friendships and you make it possible for friends to end your public career. Which is why, if you place a high value on loyal friendship, politics may not be your best life choice. Or, if you want to succeed in politics while still enjoying the pleasures of loyal friends, the old Washington adage has been to get a dog.

“Friendship’s the privilege of private men, for wretched greatness knows no blessing so substantial,” wrote 17th-century poet and dramatist Nahum Tate. Friendship is facilitated by a rough equality in status. That makes it hard for kings or presidents or CEOs to find fellows sufficiently elevated.

Beyond disparate fortune, there’s another question. A ruler can’t afford to let sentimental attachments or conflicting obligations take primacy over his commitment to the public interest. At least that’s the most positive way to put it. The realpolitik version is to note that leaders don’t last very long if they don’t do what it takes to maintain, expand, and defend their power.

When Shakespeare’s Prince Hal becomes King Henry, he gives Falstaff the heave-ho, not because the king is a jerk but because monarchs can’t afford to be loyal to their old drinking buddies. Still, we feel for poor, discarded Falstaff and we dislike the new, ruthless Henry, described by W.H. Auden as a “Machiavellian character, master of himself and the situation.” The Bard’s Henry V, who rouses his troops to the challenge of St. Crispin’s Day, is a great, inspiring leader; sad as it is true, such leadership isn’t achieved by worrying about old friends’ feelings. Only a few scenes before the St. Crispin’s speech, Henry has Bardolph, one of the disreputable pals of his youth, hanged for looting.

Auden derided Hal as a sort of template for personal disloyalty in leaders: “Hal is the type who becomes a college president, a government head, etc., and one hates their guts.”

One hates their guts because they’re either not able or not at liberty to indulge in friendship and the loyalties that make it possible. Before the Battle of Shrewsbury, Falstaff asks Hal, on “a point of friendship,” to watch his back in the fighting and to stand astride him protectively should he fall. Hal makes a crack about how it would take a colossus to stand astride such obesity, but he does give Falstaff a straight answer about whether he can expect the prince’s loyal protection: “Say thy prayers and farewell.”

Friendship is facilitated by a rough equality in status. That makes it hard for kings or presidents or CEOs to find fellows sufficiently elevated.

Auden may be right that we hate such a Machiavel, but Hal would never have defeated the likes of Harry Hotspur if he’d been busy watching out for Falstaff—or any old friend. Savvy leaders have followed Hal’s example in putting friendship aside.

On September 2, 2005, as New Orleans drowned in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, President George W. Bush finally flew to the area, four days after the storm made landfall in Louisiana. Bush touched down at Mobile Regional Airport to meet with emergency officials and local politicians. Soon he had his arm around the shoulder of FEMA director Michael Brown and—in what’s now widely regarded as the moment America turned on the Bush administration—proclaimed, “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.” What was Bush doing other than loyally supporting a subordinate—someone he knew well enough to have christened with a nickname?

Clearly, there are limits to the efficacy of loyalty. As Jacob Weisberg, then editor of the online magazine Slate, put it, loyalty is “the most overrated virtue in politics.”

In this view, loyalty isn’t just overrated but a vice. “Presidents who fixated on personal allegiance, such as Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and George W. Bush, tended to perform far worse in office,” Weisberg argued. Such leaders become insular and paranoid, devolving “toward a Mafia view of politics that lends itself to abuse of power.”

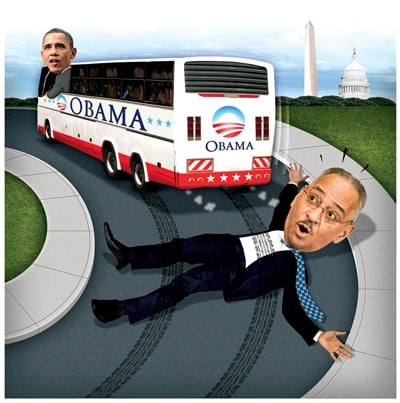

But it’s an indication of loyalty’s tug that even Weisberg couldn’t help sneaking back in an appreciation of it. In a January 2010 story, he tried to explain why Obama’s appeal and approval were slipping. Weisberg suspected that the electorate was feeling distanced and disaffected by the President’s “cool, detached temperament.” The problem, he wrote, wasn’t that people didn’t admire Obama but that they didn’t “come away from any encounter feeling closer to him.” Why not? Because Obama “is not warm,” nor is he “deeply involved with others.” And perhaps most problematic: He is “not loyal.”

Just eight months before, Weisberg had praised Obama for his “healthy disdain for the overrated virtue of political loyalty.” And yet the writer couldn’t help noting that it was “slightly chilling to watch” how ruthless Obama was in discarding anyone who became inconvenient: “If you’re useful, you can hang around with him,” Weisberg observed. “If you start to look like a liability, enjoy your time with the wolves.”

It didn’t take Obama long—despite all his admirers’ talk of “human loyalty and love”—to learn what to do with his Falstaffs and Bardolphs. And though it may be right and it may be effective, it isn’t attractive. Which shows just how tricky loyalty is for leaders. They can’t afford to be sentimental, nor can they afford to be unattractive. They can’t afford to be ruled by personal attachments or to be seen as callous or cruel.

Next: Is there room for loyalty to leaders?

There may not be much room for loyalty from leaders, but what about loyalty to leaders? What sort of leaders demand it—and what kind do they ask for? Lyndon Johnson once explained what he sought in an assistant: “I don’t want loyalty. I want loyalty. I want him to kiss my ass in Macy’s window at high noon and tell me it smells like roses.”

Johnson was less interested in the quality of advice he was getting from his aides than in their loyalty. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara came in for special praise. “If you asked those boys in the Cabinet to run through a buzz saw for their President, Bob McNamara would be the first to go through it,” Johnson said.

Could it be that buzz-saw-braving loyalty was the very quality that made McNamara such a disastrous steward of Vietnam policy? McNamara was part of the group-thinking Johnson advisers who, as columnist James Reston put it, “gave to the President the loyalty they owed to the country.”

The virtue of loyalty has never quite recovered from the damage of back-to-back administrations that put personal allegiance over the public interest. As if Johnson’s demands for bad epistemic conduct—the philosopher’s term of art for a willingness to believe things you know aren’t true—weren’t bad enough, next up was Richard Nixon, whose obsession with loyalty set the stage for Watergate.

Well before the break-in, Nixon and his enablers established that loyalty would be the measure of success for executive-branch staff. Just after Nixon was elected, Pentagon procurement bureaucrat A. Ernest Fitzgerald made the mistake of telling Congress there were cost overruns of $2 billion on C-5A planes. The White House had Fitzgerald sacked. An aide to chief of staff H.R. Haldeman explained the firing in an internal memo: “Fitzgerald is no doubt a top-notch cost expert, but he must be given very low marks in loyalty; and after all, loyalty is the name of the game.”

Come summer 1971, Nixon’s obsession with loyalty had blossomed into full-blown, paranoid us-versus-themism. When a small drop in unemployment didn’t get the media play he wanted, he became convinced that the Bureau of Labor Statistics was trying to hobble him by shrugging off good news as a statistical anomaly. He even had a reason why the staff of the BLS was supposedly spinning against him: disloyalty born of being Jewish.

“The government is full of Jews,” Nixon told Haldeman. “Most Jews are disloyal. Generally speaking, you can’t trust the bastards. They turn on you.”

“That’s right,” said Haldeman.

“It does not matter if that loyalty was misguided, misplaced, unreciprocated, or anything else. Loyalty per se […] is not a crime.”

You can’t help but conclude that the President would have been better served by advisers willing to shoot straight, to tell him the truth even if that meant contradicting him. It’s clear Nixon had enjoyed yes men for too long when he could so comfortably launch into noxious anti-Semitic rants. But truth-telling was seen as dissent.

“Dissent and disloyalty were concepts that were never sufficiently differentiated in their minds,” said Jerome H. Jaffe, a psychiatrist who was Nixon’s drug czar. He described an organization in which concern for anything other than the President’s druthers was seen as a betrayal. “That really was the tragic part,” he told a reporter. “To dissent was to be disloyal. That is the theme that recurred again and again.”

So thoroughly did the theme define the organizational culture that merely withholding dissent wasn’t good enough; one had to be willing to kneecap anyone who dared to disagree. The President expected his capos to deal with anyone who presented a problem, and there was no tolerance for such niceties as worry over how someone’s career might be damaged. “Such a concern was viewed as a fatal flaw,” Jaffe said.

But once Watergate had taken its toll and all the President’s men were headed for the hoosegow, the very advisers whose blinkered allegiance had contributed to the national calamity asked for leniency on the grounds that they were simply being loyal.

Nixon attorney general John Mitchell’s lawyer argued that loyalty was a noble thing to be rewarded regardless of the outcome: “It does not matter if that loyalty was misguided, misplaced, unreciprocated, or anything else,” William Hundley said in his closing argument in federal court, where he was defending Mitchell on Watergate-related charges. “Loyalty per se, you will agree, is not a crime.”

Perhaps. But loyalty may aid and abet crime. And leaders looking for loyalists, whether in politics or business, may be interested in lackeys willing to cut corners or worse.

Watergate special counsel Archibald Cox—who was fired by Nixon when he wouldn’t circumscribe his investigation—recalled that the President’s downfall “serves as a reminder that there are limits to the kind of loyalty that is owed and should be given.”

Next: What happens when the loyalty isn't there?

So what kind of loyalty is appropriate? What does it mean for an employee or aide to be loyal? Take Jack Lemmon as the poor schnook in Billy Wilder’s film The Apartment. He’s been letting his superiors use his flat for extramarital assignations. The top boss, played by Fred MacMurray, gets wind of the deal and, with trysts of his own to arrange, calls Lemmon into his office. “Been hearing some nice things about you,” MacMurray begins. Then he reads from a report by Lemmon’s supervisor: “Loyal, cooperative, and resourceful.”

“Loyal” is the dead giveaway—the key word identifying Lemmon as willing to organize a shabby little conspiracy. Soon Lemmon has given MacMurray the key to the apartment and is rewarded with a promotion.

Presidential candidate John Edwards made MacMurray look like the soul of propriety. When one of his aides confronted him, urging him to end his affair with Rielle Hunter, Edwards saw it as a betrayal. “You work for me,” he said, making a blunt and angry statement of what loyalty meant to him. “I trusted you like a son, but you broke my trust.”

After the Edwards campaign slouched into oblivion, plenty of observers concluded that the candidate’s aides had broken a trust more important than any they owed their well-coifed boss. What of their obligation to their party? And to the nation, which didn’t need another dimestore lothario at the helm imposing his vulnerabilities on the country?

This is the whistleblower’s dilemma. Do you keep faith with the person you work for? With the company? Or are those parochial loyalties impediments to doing the right thing? We can’t say that following some moral principle is always the right choice—plenty are the traitors who are able to justify immensely damaging treason on the grounds that they were following their own consciences. One man’s principled whistleblower is another’s self-righteous backstabber. There may be no clear way to determine which is which.

But given how quickly organizations and societies disintegrate when loyalty ceases to matter, I’m inclined to make loyalty the default setting that requires a preponderance of damaging evidence before it can be overridden. And so we might approach our leaders in the same way Aristotle suggested regarding friends whose morals may have slipped into error: Don’t abandon them unless they exhibit an excess of wickedness.

The loyalty Edwards expected in his team was fidelity to him alone. He sought Lemmon-like servility and found it in Andrew Young, an aide whose notion of employee devotion included not only pretending to be the “baby daddy” of Edwards’s love child but enlisting his own wife in the conspiracy. Young was willing to endure humiliation, ridicule, and personal ruin for Edwards—the very definition of loyalty! But that doesn’t mean he was actually expecting to suffer. Young was counting on being well rewarded. Instead, when the skulking was over, all Edwards proposed to give him for his troubles was a job reference. (The text of such a reference would write itself: “Loyal, cooperative, and resourceful . . . .”)

Young was not happy. He confronted his old boss: “I then explained that I had the sex video”—the one that Edwards’s very pregnant mistress had made of one of her romps with him. Young also threatened to make public “a small library of pertinent text messages [and] voice-mail recordings by the score.” Edwards gave him the brush, leading Young to conclude that his former boss “was a remorseless and predatory creature.”

Harsh words from a conspirator who would ultimately cash in with a tell-all book—but a fitting end to a relationship defined by demands for degrading loyalty.

As dangerous as loyalty can be, legitimate loyalty is essential to getting anything done, whether in a business or in a bureaucracy. General Colin Powell made loyalty one of the cornerstones of his military career, arguing that success came from “hard work, learning from failure, loyalty to those for whom you work, and persistence.” He explained his idea of what loyalty to a leader meant:

“When we are debating an issue, loyalty means giving me your honest opinion, whether you think I’ll like it or not. Disagreement, at this stage, stimulates me. But once a decision has been made, the debate ends. From that point on, loyalty means executing the decision as if it were your own.”

As dangerous as loyalty can be, legitimate loyalty is essential to getting anything done, whether in a business or in a bureaucracy.

This is not blinkered tell-me-what-I-want-to-hear fidelity. It leaves plenty of room for—indeed demands—uncomfortable truth-telling. At least the truth as each participant in the discussion sees it. Not everyone is going to agree on what facts are salient or the best course of action. But if an organization is to have any coherent course of action, people need to act with unanimity of purpose once that course has finally been decided. Loyalty in this context boils down to a commitment to respecting a legitimate process.

It’s not unlike the basic deal made by candidates in primary elections. If I’m running for my party’s nomination for some office, I may think—and even vociferously make the case—that my opponent is an idiot, dangerous, or worse. But if he gets a few more votes than I do, I’m duty-bound not only to recognize him as the winner but to support him and campaign for him in the general election. Similarly, working in an organization, I may put forward my own ideas about the direction the business or bureaucracy should go, but if my ideas aren’t the ones to win the day, I should be ready to support the decision that’s made.

Or shouldn’t I? Is it right to throw yourself into a policy you believe to be wrong? Shouldn’t we always insist on what we think is right? Not necessarily. By participating in the process of an organization, we make a promise to support the outcome of the process. And when members of an organization aren’t willing to let the decision of the group overrule their own opinions, the organization falls apart.

We all have a stake in our own views. You could say there’s some small measure of suffering whenever we have to abandon our pet projects, championing opinions we regard as stepchildren. A willingness to bear that displeasure can be seen as loyalty either to a leader or to the organization he leads. Regardless, loyalty helps get things done.

And so movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn may have had good reason for saying of his employees, “I’ll take 50 percent efficiency to get 100 percent loyalty.” Efficient men all going off efficiently in their own directions don’t get nearly as much done as a group of less capable ones reliably rowing in unison.

Next: Smart leaders who find ways to ease demands

If loyalty gets the credit for holding organizations together and keeping fractious groups focused on achieving some policy goal, when the policy in question proves problematic, loyalty takes the blame. All of a sudden it’s transformed into that unfortunate stuff that makes men acquiesce in dubious decisions against their better judgment. How fragile a virtue to be at the mercy of such vagaries, but so it is.

Many have argued that the loyalty that served Colin Powell so well through his military career was ultimately his undoing. Having argued with President George W. Bush against the plan to invade Iraq in 2003, Secretary of State Powell fell into line when Bush decided that Saddam Hussein had to go. It was Powell who was dispatched to the United Nations to make the case that Iraq was bristling with chemical and biological weapons. When those claims proved wrong, Powell’s prestige was profoundly diminished. Though he’d later insist he was truly convinced Saddam’s arsenal was stuffed with weapons of mass destruction, it’s hard to believe that the dovish Powell would have done the official saber-rattling had it not been for his loyal commitment to execute the decision as if it were his own.

Smart leaders are the ones who find ways to ease the demands put on loyalty, who are able to keep their crews sailing on course without excessive appeals to duty. World War II and Korean War general Douglas MacArthur, instead of simply demanding that his subordinates fall into line behind his decisions, went to elaborate lengths to make his junior officers think that every decision went their way.

“MacArthur has a wonderful knack of leading a discussion up to the point of a decision that each member present believes he himself originated,” according to General George Kenney, who was on MacArthur’s staff in the Pacific. “I have heard officers say many times, ‘The Old Man bought my idea,’ when it was something that weeks before I had heard MacArthur decide to do.” Kenney recognized that as a salesman “MacArthur has no superior and few equals.” It was a skill that banked loyalty rather than drawing it down. If only MacArthur had thought to lavish some of that loyalty-building salesmanship on his ultimate superior, President Harry Truman might not have handed him his gold-braided hat.

Smart leaders are the ones who find ways to ease the demands put on loyalty, who are able to keep their crews sailing on course without excessive appeals to duty.

Richard Neustadt argues in his classic text on executive authority, Presidential Power, that a leader’s primary asset is his power of persuasion. According to Neustadt, a successful President never stops persuading—the people, Congress, the bureaucracy, his own staff—that what he wants done is what’s in their own best interest. Like MacArthur with his junior officers, an effective President encourages cooperation by convincing people that his decisions are really their decisions.

There’s a lot to be said for this take on power politics, but Neustadt misses something—that a President who has to persuade everyone of everything all the time is a President who can’t help but be hobbled and exhausted. Yes, on the big things he may need to make the case to his administration so that they’re onboard and enthusiastic. But as a day-to-day matter, a President has to be able to count on his people to do what he wants done, relying on a combination of respect for the authority of his office (which is itself a loyalty to the constitutional powers he commands) as well as the more direct sort of loyalty to him.

If failing to convince a given staffer meant only that the aide would be unenthusiastic and inefficient, Presidents might not care so much about making sure everyone was onboard. But anyone with access to confidential discussions is in a position to hijack policymaking. Without loyalty to constrain aides, it’s all too easy for them to get their way by means of leaking. No leader can succeed if those working for him are in the habit of surreptitiously undoing his decisions.

No wonder Presidents are always trying to plug leaks.

Nixon had his ill-fated plumbers and, even after their efforts demonstrated the risks of going on leak hunts, Presidents have continued to get riled by what they see as acts of disloyalty by their staff. During Obama’s extended period of deliberation over which policy to pursue in Afghanistan, someone leaked General Stanley McChrystal’s presidential briefing report to journalist Bob Woodward. Obama was not happy: “For people to be releasing information during the course of deliberations, where we haven’t made final decisions yet, I think is not appropriate.” He called the leak a firing offense.

It’s easy to see how the staffer justified slipping the document to Woodward—he no doubt thought the President was dithering, leaving soldiers in harm’s way. The leaker likely thought he was acting in the best interest of the troops and the country by forcing the President’s wavering hand. But what the leaker was actually doing, as is often the case with leakers, was attempting to impose his will on the President. And what right did he have to do so? No one elected the leaker; he isn’t the one ultimately responsible for the policy.

Next: "You work with him because he's got the job."

Disloyalty has become the norm for political professionals. Once upon a time, aides felt duty-bound to keep their bosses’ private conversations private. No more. We live in the age of the dishy memoir, a disloyal idiom as destructive of political relationships as it is of love and marriage. Former senator Bob Kerrey lamented that political loyalty has been crushed by an avalanche of cash available to ambitious advisers and aides eager to make themselves look good by making their old bosses look bad: “There’s money in being disloyal,” he said, whether in the form of a blabbing book deal or a retainer for TV punditry.

Given the well-documented hazards of political loyalty, shouldn’t the trend to abandon it prove to be a public good? Yes, too much loyalty—or at least too much of the wrong sort—ends up stifling the dissent necessary for a thorough discussion and consideration of the issues. A President surrounded by yes men is one who hears only the echo of his own views and misses the information and analysis he needs to make good decisions.

But too little loyalty is just as damaging to healthy debate. Who can be open and honest when he’s worried about how his every word will be parsed in the media? If you’ve ever known a compulsive blogger or tweeter, you have a sense of the candor-crushing nature of total disclosure. You wouldn’t speak freely to a friend who posts your unguarded comments online (or if you did, you’d learn not to do so again). The same goes quadruple for politicians. “We already don’t write things down for fear of having the documents subpoenaed,” Kerrey told the New York Times. “Now, in a meeting, you’ll have people staring at each other afraid to say anything—for fear that it’ll end up in a book.”

Kerrey is right about the problem, though maybe it isn’t as new a phenomenon as it might seem. Oscar Wilde observed more than a century before, “Every great man nowadays has his disciples, and it is always Judas who writes the biography.”

Is it any wonder politicians are now requiring staff to sign the sort of nondisclosure agreements that celebrities have long used to keep staff from selling secrets to the tabloids? Even politicians’ wives have resorted to such legalisms: When Rudy Giuliani was running for President, his wife got his aides together over dinner for some strategizing one evening and began the festivities by having her assistant give each of them a nondisclosure contract. It may seem paranoid or excessive, but can you blame her? After all, even with the contracts signed by all in attendance, someone later told every detail of that evening’s conversation to reporters working up a book on the campaign.

Nondisclosure agreements are “our new loyalty oaths,” writes journalist Christine Rosen—necessary, she laments, because “we trade our professional loyalties for a mess of published pottage.” What was once governed by a code of personal decency and loyalty now has to be governed by crass contractual obligation. There’s no room left for anything so quaint as reticence.

But what of those dilemmas when a leader expects his subordinates to subordinate their consciences? Where there are two objects of loyalty—(1) a person and (2) the Constitution—there are bound to be irreconcilable conflicts between competing obligations.

Take Jiggs Casey, the colonel played by Kirk Douglas in the political thriller Seven Days in May. He’s a loyal right-hand man to his mentor, Burt Lancaster’s General James Mattoon Scott. Lancaster counts on Douglas to back him in a military coup. When Douglas refuses—and exposes the plot—Lancaster is infuriated: “Do you know who Judas was?”

“Yes, I know who Judas was,” Douglas spits back. “He was a man I worked for and admired until he disgraced the four stars on his uniform.”

Dramatic as it may be, this conflict isn’t much of a dilemma. The conflict of competing loyalties Kirk Douglas’s character faces is easily resolved. Douglas is right to decide that his loyalty to Lancaster is null once Lancaster has proven himself disloyal to the country. That’s not because of some reverse–E.M. Forster maxim asserting that friends must always be betrayed before country. Rather, the conflict is easily resolved because there is no friendship to betray—theirs is a different sort of relationship, that of leader and subordinate. Lancaster’s mistake is to think that Douglas should be loyal to him on a personal level. But their relationship was established and shaped by the legal structure governing the military. Theirs is a bond forged through the giving and taking of orders, orders that have force because of the oath both men have sworn.

In the book and later the film The Caine Mutiny, a smart, sophisticated, and disgruntled junior Navy officer convinces his credulous comrades that their captain is cracked. Captain Queeg helps in that endeavor by being a bit of a wreck—there’s the nervous fumbling with those steel worry balls, the obsession with phantom strawberries, and the yellow-stained weakness under fire. We end up rooting for the men who take command of the ship in a storm. We find ourselves agreeing that Queeg didn’t deserve to command, and our sentiments are with the mutineers as they stand trial.

But we’re wrong, and author Herman Wouk means for us to be startled into the realization we’re wrong. In the movie’s climax, the mutineers are celebrating their acquittal. Their lawyer, disgusted with having gotten them off, confronts them: “Queeg came to you guys for help, and you turned him down, didn’t you?” the lawyer says. “He wasn’t worthy of your loyalty. So you turned on him. You made up songs about him. If you’d given Queeg the loyalty he needed, do you suppose the whole issue would have come up in the typhoon?” He then hammers it home: “You don’t work with a captain because you like the way he parts his hair. You work with him because he’s got the job, or you’re no good.”

For all the twists and turns loyalty pretzels itself up with, that blunt statement rings true. We have a visceral response to the disloyal—they’re just no damn good. Still, we can’t escape our ambivalence. As much as we share in the judgment that the disloyal are no-goodniks, we don’t much trust loyalists. We’re leery of company men; and in the political world we deride those whom George Bernard Shaw called “good party people” as unimaginative hacks. They take their loyalty to be a virtue, and we dismiss them for it. We suspect Shaw was right in saying, “In politics there should be no loyalty except to the public good.” But when it comes to endeavors that require some coordinated effort, having everyone act on his own stubborn convictions may not do the public much good.

Whether the endeavor is a ship or the ship of state, there can be no effective leadership without some measure of loyalty. We may not like it—the pitfalls are obvious—but there’s no escaping it. “Leadership,” as political theorist Judith Shklar put it, “for better or worse involves fidelity.”

This article is adapted from Loyalty: The Vexing Virtue, copyright © 2011 by Eric Felten. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster in the May 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.