The Oval Office has the afternoon off. Its storied furnishings—the Resolute Desk, the presidential chair, those Romulus and Remus sofas—are all tucked under plastic sheeting to keep everything pristine until POTUS’s next crisis.

Right now, the world’s most celebrated workplace looks unexpectedly like a moribund showroom in Queens.

That’s more or less the case. In a frowsy crag of Long Island City, executive producer Lori McCreary is showing me around the crammed soundstage that’s home to CBS’s Madam Secretary, starring Téa Leoni as the President’s surprise pick to run Foggy Bottom after her predecessor’s fishy death in a plane crash. I’m here to see how the entertainment biz constructs its version of Washington. Wryly, McCreary confides that she sometimes looks at prime time’s other fake Oval Offices and wonders where they got their curtains.

Unless you’re the kind of monomaniac who watches only cable news, you know she’s got plenty of competition to check out. Whether they’re satiric, sensationally soapy, or gleefully Machiavellian, inside-dish looks at DC power players are in vogue on TV as never before. What sets Madam Secretary apart from Veep and Scandal and House of Cards is that, relatively speaking, it’s the earnest one. Instead of egging on the audience to cackle at the capital’s Monster Mash, McCreary and her cohort want to “shine a light” on the noble side of public service via Leoni’s Elizabeth McCord and her husband, Henry—people who aren’t gargoyles like HoC’s Frank and Claire Underwood, people whose private emotions and everyday concerns viewers from Oshkosh to Biloxi can identify with.

This makes sense, given the show’s provenance. A lively, astute woman in her early fifties who earned a 1984 computer-science degree at UCLA, McCreary runs the humbly named Revelations Entertainment, actor Morgan Freeman’s production company—and Freeman, needless to say, favors uplift, not alienation. “It’s our instinct to do something that inspires people to their better selves,” McCreary tells me.

That laudable goal doesn’t make Madam Secretary any less preposterous, especially to an old State Department brat like me. The quibbles start with Leoni’s hairstyle, because no Secretary of State would risk looking that girly. Then there are all those swiftly resolved international high jinks week in and week out, so unlike the Foggy Bottom grind. Funniest of all is what I call the Star Trek effect, because McCord is supposedly overseeing a bureaucracy whose size dwarfs the Enterprise crew and yet the same half dozen subordinates soak up most of the screen time.

Such gripes put me squarely in the great Washington tradition of advertising our knowledge of the real thing by finding fault with everything TV shows and movies bungle about life here. Even so, my hunch is we’re more cognizant than we let on that our grousing doesn’t have beans to do with whether they succeed as entertainment—which is, after all, the point. Madam Secretary was Sunday night’s top-rated scripted broadcast last season, which means they must be doing something right. That almost certainly includes the stuff Washingtonians think they do wrong.

• • •

Verisimilitude can be the hobgoblin of little minds.

I’ve spent enough time in LA to know that the people who make these shows are often neither dumb nor ignorant. They’ve just got other priorities besides strict accuracy. So I got curious about the process—not only the creative choices involved but the practical side of contriving our town’s fake TV doppelgängers.

I guess it’s a DC vice always to want to find out how the sausage gets made. That’s how I’ve ended up in Queens, watching Leoni film a scene with Tim Daly (as the Secretary’s husband), Keith Carradine (as the President), and Željko Ivanek (as the White House chief of staff). Or sort of watching, as the actors and camera crew are cloistered in another room. Everyone else—including the episode’s director, its writer, McCreary, and me—is hunched in front of a trio of monitors in the mockup White House corridor next door, eavesdropped on by a merry bust of FDR that looks much more slapdash in real life.

The main reason Madam Secretary is filmed in New York is that Leoni wouldn’t have signed on otherwise. Only bits of the pilot were shot in Washington, something McCreary says they hope to reprise down the road: “Hopefully third season, we’ll have the bucks to do that.” Back when Madam Secretary’s durability was anybody’s guess, the production designers made do with the Waldorf Astoria as a substitute for DC’s architectural pomp. But that changed once the show got renewed for the second season it’s cruising through now. Domestic scenes are shot on Soundstage G, as in “Georgetown”; on this day, we’re on Soundstage F, as in “Federal.”

The State Department sets are in yet another barn about five minutes away, and nearly everything else—the foreign locales included—is impersonated by look-alike bits of the Big Apple, from the McCords’ Georgetown nabe (really Brooklyn’s Park Slope) to Cuba (Far Rockaway, believe it or not). As all the writing and postproduction are done on the West Coast, that makes for a whole lot of—gee, should we call it shuttle diplomacy?—between New York and LA.

Daly needs several passes to nail his key line. “She wasn’t one of Jibral Disah’s existing wives,” he says over and over. “She was his new bride.” But nobody calls “Cut!” when he or someone else falters. The actors just pick up where they left off while the cameras keep running. This is, after all, old-school network TV—with only eight days to shoot each episode and 23 episodes to crank out this season. The atmosphere of controlled haste as the winter afternoon wanes makes achieving perfection a luxury.

Curiously, that’s a feeling that any White House factotum or stressed DoD number cruncher can probably recognize. As Daly says, “She was his new bride,” one last time and I head for the exit, the divergences between TV’s Washington and the genuine article are starting to seem beside the point. What’s truly striking—well, droll, anyhow—is the similarities behind the scenes: the combined idealism and calculation, the multiple cooks and bailiwicks, the gaps between high-minded conceptualizing and harried execution. If Madam Secretary has a backhanded claim to authenticity, it’s that the way the show is put together so uncannily mimics the simultaneously bureaucratic and extemporized government milieu it’s about.

• • •

Cut to Randy Newman singing “I Love L.A.”

On the other side of the continent, in Madam Secretary’s wing of a Santa Monica media facility that also houses Fargo’s brain trust, a half dozen or so of the show’s writers are congregating for their daily strategy session in what a placard tells me is jokily called—c’mon, one guess—the Situation Room. Only the California sunlight flooding its windows mars its resemblance to its clones in Queens and Washington.

The writers are waiting for their boss, veteran TV writer/producer Barbara Hall—Madam Secretary’s Madam Secretary, you could say. In fact, the show began with the “tiny spark” of an idea McCreary had after watching Hillary Clinton at the 2012 Benghazi hearings: “I wonder what she’s going to go home and say to Bill,” she said to herself. Hence Madam Secretary’s dual emphasis on the heroine’s high-octane job and her life with Henry McCord and their three kids. But Hall was the industry pro brought on to turn McCreary’s question into character-driven drama, and that’s why, in the weird rules of Hollywood, she gets a “created by” credit.

Inventive family fare, not in-your-face provocation, has always been Hall’s turf, and dramatizing international relations was a new task for her. But she knows a lot about being a woman in a man’s world, which is the aspect of Elizabeth McCord’s situation that transplants her and McCreary’s own experience to Washington. Says Hall: “Being in a position that’s usually held by men can be the same in every industry.”

As it happens, Hall is someone I’ve known off and on since she was a 24-year-old Los Angeles newbie writing jokes for Newhart. Back then, she was giddy and laughed a lot and—well, she still laughs a lot, but 30-odd years in the business can add a fair amount of shrewdness and resilience to somebody’s face. Because she’s an old hand at crafting engaging network TV, I’m not surprised to hear that, like Leoni, she had one condition for coming aboard: It can’t be Hillary, she told her prospective partners firmly. And indeed, Elizabeth McCord isn’t, not least because her husband—a fellow college prof until the presidential summons uproots them both—most definitely is not Bill.

Even though everyone I ask denies noticing the similarity, the scene around the writers’ table virtually duplicates Elizabeth McCord’s sessions with her staff. They all sit around a room pitching ideas for Hall’s approval, and then one of them retreats to his or her laptop to write a scene about the heroine’s wonky seventh-floor crew pitching ideas for her approval. Once Hall takes her seat at the table’s far end, she doesn’t weigh in that often. But she hardly needs to, because everything’s presented for her benefit. A thoughtful fellow named David Grae, who got his start writing for Hall’s Joan of Arcadia, briefs her on the latest modifications of the current script, which involves a Pakistani nuke being transported when it strays into India and Elizabeth McCord having to mollify both countries before all hell breaks loose. “Elizabeth is pitching that they can use this as an opportunity to work together,” Grae explains.

Then everyone chips in to work out the premise’s complications: India’s moves, Pakistan’s countermoves, the US involvement. The whiteboard anatomizing the episode’s teaser, act one, act two, and so on is a forest of migraine-inducing squiggles when Grae abruptly asks the room, “Does anybody really think that this is how they’d do it?”

But so far as I can tell, the process is too far along for the question to be more than rhetorical. Instead, because “within the realm of possibility” is Madam Secretary’s mantra, Grae gets curious about American military capabilities on the Indian subcontinent: “We have a base in Pakistan, don’t we? We have one in India, I think.”

Somebody Googles to check. “We have a big old base in the Indian Ocean. But it’s, um, kind of far away from India.”

Hall speaks up for the first time. “I’m worried that she’s only talking to India,” she says, meaning McCord—and also sounding not totally unlike her. “She’s not talking to Pakistan.”

Quickly, Grae agrees: “I think somebody has to be talking to Pakistan.”

“Are we at the same time managing the world response to this? Is she? I don’t want this to feel like it’s happening in a vacuum,” Hall says. “Or—there’s no way to keep it quiet, right?”

“I don’t think India would have any reason to. We can nod to the idea the world is watching.” Grae turns jocular: “ ‘Yeah, thanks. We’re working on it. Thanks for your input. Au revoir!’ ”

“Okay, but I think our act-one kicker is too much like the one in the teaser,” another writer interjects.

“No,” says Grae. “That was a ‘what the hell?’ moment. This is a ‘holy f—!’ moment.” Joe Biden couldn’t have put it better.

• • •

It’s only when everybody breaks for lunch that I learn that at least a couple of the people involved in Madam Secretary used to play the “what TV gets wrong about Washington” game from the other side of the fence.

Writers Alex Cooley and Alex Maggio are both Washington refugees themselves, undermining my cheerful guess that none of Hall’s crew would know a security clearance from a shopping coupon in real life.

Fresh out of college, Maggio worked as a Defense Intelligence Agency analyst in Anacostia while honing his future Jeopardy! skills playing bar trivia in DC saloons. (He was a three-time champ in 2015.) Frustration with his job’s minimal impact pushed him west to get a playwriting master’s degree at UCLA instead, and he’s probably only half joking—if that—when he calls his Madam Secretary gig a way of atoning for leaving government service.

“If I can’t work with the people who serve our country in real life, the least I can do is pay them homage in fiction,” Maggio tells me later by e-mail. Over lunch, he’s more bumptious: “The biggest difference between what we do and the real thing is that the real thing is a lot more boring.”

I used to be one of those people.

The other Alex turns out to be a member of my own tribe: someone who spent time as part of the State Department’s great superpower diaspora. The daughter of Foreign Service officer Alford Cooley, she grew up partly in Zurich—“It reminded me of Playmobil, except there weren’t animals driving the fire trucks”—and partly in McLean. As a child, she planned on becoming an FSO herself, but a stint at the Harvard Lampoon lured her first to Vice magazine and then, at age 25, The Colbert Report.

“I used to be one of those people,” Cooley tells me when I bring up how District lifers love to quarrel with La La Land’s depictions of them. She can still sympathize, too: “They’re really doing this work, and if you see it sort of glamorized or glossed over, I think you can feel a little galled. But we’re not there to show the mundanity of reality—that’s not why you watch TV. The purpose of drama is more to reflect the emotional truths, and I think we do a good job of that.”

Even so, Hall’s perspective on Washington is the decisive one. Though you’d hardly guess it except for a down-home accent she can mute or dial up at will, she grew up just outside Danville, Virginia—yup, as in the Band’s old lyric, “I served on the Danville train.” That made Washington a constant Emerald City presence in her youth—“It’s your, you know, fancy relative”—and later the place to see Bob Dylan, Springsteen, and Tom Petty concerts during her undergrad days at James Madison University. It’s not an accident that Elizabeth McCord is a Virginian, raised “in the shadow” of DC, but more outsider than true denizen. “I had to do Washington the way I experienced it,” Hall says.

She also knows that her brand of positivist TV—“aspirational” is the word she and McCreary both like—doesn’t have the cachet it once did. But doing something darker isn’t in her: “The show isn’t cynical because I’m not cynical. I think there’s something virtuous driving people in Washington that we don’t give them enough credit for.”

Untempted by cable, aside from a brief job writing for Homeland, Hall also admits to “thriving” on broadcast TV’s constraints. “There’s something about being restricted that makes you more creative, and there’s something about the challenge of seeking a broader audience that I enjoy,” she says. Alex Cooley seconds the thought: “Cable is Breaking Bad, and we’re not. We’re Breaking Good.”

• • •

And yes: from Hall on down, everybody involved knows that real-life Secretaries of State don’t tidily solve a hellzapoppin’ international crisis every week.

But they draw a line between conscious hyperbole and uninformed fantasy. “What we can get right we try to get right,” McCreary tells me—with vetting help from onetime Al Gore wallah Michael Feldman’s consulting outfit, the Glover Park Group, which has also helped bake authentic nuts and bolts into the Hollywood pies of, among others, American Sniper.

Some of the show’s conscious distortions are no-brainers. “You notice our State Department has very beautiful paneled walls,” McCreary says. “Well, there are parts of the State Department that look like that, but not the entire State Department! Some of the offices look like a 1970s hospital.” (Too true.) When I ask Feldman and his colleague Adam Blickstein about Madam Secretary’s more fanciful story lines, they turn Santa’s-elf jolly. “We don’t have veto power over content,” says Feldman. Adds Blickstein: “If they listened to us on all matters, it would be a very boring TV show.”

As everyone reminds me, the series isn’t designed for the cognoscenti. Though the hope is to give non-Washington audiences “a fictional look behind the curtain” that isn’t altogether inaccurate regarding the dilemmas of superpower diplomacy, that little word “fictional” does give the show latitude to commit what Alex Maggio calls “venial” sins. “Like talking on secure landlines instead of a SCIF,” he amplifies, flattering me by assuming I know the shorthand for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility. (I don’t.)

Fanciful or not, a few of Madam Secretary’s plot lines have ended up anticipating or mirroring real-world events, from the Iran nuclear deal—the show’s version was a full-on peace treaty—to Obama’s normalization of relations with Cuba.

“Really, honestly, it’s because there are only so many ways things can work out, and sometimes it goes the way we imagined it,” says Hall. She was tickled when a BBC interviewer tried to get her to admit that the White House uses her series as a conduit for foreign-policy trial balloons.

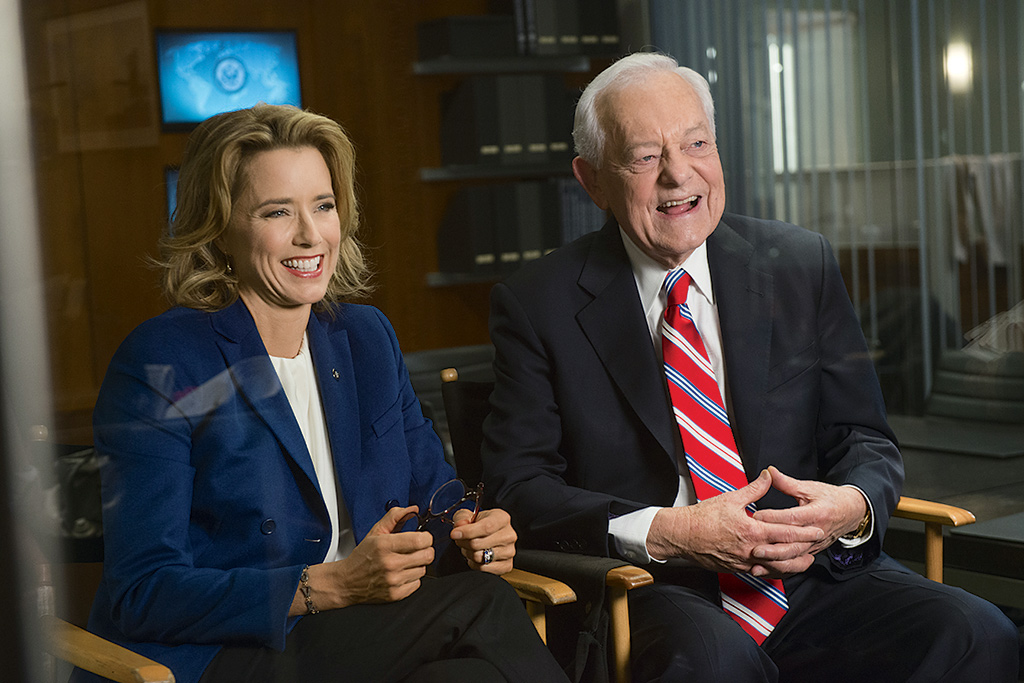

A different sort of intersection of fiction and reality was former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s cameo as herself last fall. It came about when she, Leoni, Daly, McCreary, and Hall were all guests at CBS newsman Bob Schieffer’s table at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner and one of the actors suggested it on the spur of the moment, not expecting to be taken seriously until Albright reacted with enthusiasm. An amused Hall recalls the conversation: “ ‘Do you really want to be on the show?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Do you want to play yourself?’ ‘Oh, yes.’ ”

Once the episode was written, McCreary got a call from Albright’s office that nonplussed her. “Nobody’s ever called me about the protocol for script notes,” she says. But it was worth it because both McCreary’s and Hall’s favorite of Albright’s lines—“There’s plenty of room in the world for mediocre men; there is no room for mediocre women”—was the real-life Madam Secretary’s own contribution.

Well, one of the real-life Madam Secretaries. True, Hall insisted before signing on—and still does—that Elizabeth McCord had better not be mistaken for Hillary Clinton. But a certain Democratic presidential candidate remains McCord’s most obvious analogue just the same, and Clinton has called the show one of her two TV guilty pleasures along with, a mite more provocatively, The Good Wife. Hall was slightly nettled about that “guilty” part, but McCreary says, “Yes, I have it on good authority that she watches regularly. Somebody asked her if she’d be on it, and she said, ‘Maybe after—in a while.’ ”

Tom Carson (@tomcarsonwriter on Twitter) is a freelance culture critic and the author, most recently, of “Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter,” a novel.

This article appears in our May 2016 issue of Washingtonian.