Six months before 1963’s historic March on Washington, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy went on his own march—a 50-mile one.

Donning a pair of leather oxford loafers and dress pants, the President’s younger brother set off from Great Falls at 5 am, traipsing through snow and slush along the C&O Canal all the way to Harpers Ferry. His four aides and his dog having dropped out along the way from exhaustion, RFK finished the walk in 17 hours and 50 minutes.

His goal? To prove that the Kennedy administration was physically fit—and to challenge the country’s citizens to be the same.

Call it a PR stunt, but Kennedy’s feat worked. Americans from high-schoolers to Boy Scouts began staging their own hikes throughout the country.

“When John F. Kennedy came in promoting fitness, here he was on the pages of newspapers waterskiing and playing touch football and sailing,” says Shelly McKenzie, author of Getting Physical: The Rise of Fitness Culture in America. “He showed that this fit life is quite a glamorous—and fun—life.”

The glamorization of fitness in that decade began with sun-kissed Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy, on a sailboat, gracing the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1960. Inside, in his article, “The Soft American,” the President-elect and Navy veteran chastised TV-watching, car-driving citizens for their lack of physical vigor. “In a very real and immediate sense,” he wrote, “our growing softness, our increasing lack of physical fitness, is a menace to our security.”

Kennedy cited a study published during the Eisenhower administration that found America’s youth to be drastically out of shape compared with European children. Almost 60 percent of US kids had failed fitness tests in strength and flexibility; 91 percent of their counterparts in Europe had passed.

The JFK administration went on to revamp predecessor Dwight D. Eisenhower’s efforts to get Americans in shape. First, a name change was in order—the President’s Council on Youth Fitness became the President’s Council on Physical Fitness, shifting the focus from young people to all Americans. Under the leadership of chair Charles “Bud” Wilkinson, head football coach at the University of Oklahoma, the council launched a nationwide media campaign among 650 TV stations and 3,500 radio stations to make the public aware of the importance of fitness.

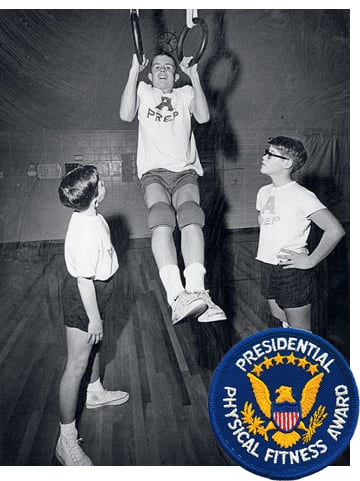

Students such as Dolly Lambdin, now 62, were required to participate in challenges, ranging from a 600-yard run to long jumps to pull-ups. To earn the presidential award for fitness excellence, a student had to score at or above the 85th percentile in each activity.

“I did well on the tests and received award badges and felt very good about that,” recalls Lambdin, president-elect of the Reston-based American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. “But I also had friends who were not as into physical activity as I was. For them, it was a torture.”

While the fitness challenges proved popular, Lambdin says that by focusing on strength and power, not overall health, they left little room for success among less athletic students: “It was a very small number of people who ended up being able to achieve the levels. People who didn’t do well on them felt bad.”

Mary Duke Smith, a personal trainer in Cabin John who attended school in Chicago in the late ’60s through the ’80s, says her most vivid memory of gym class was scoring poorly on the flexed-arm-hang challenge, which required students to hold a chin-up position anywhere from 5 to 30 seconds, depending on age and gender. “I remember it being a really significant moment for me in terms of realizing, ‘Oh, my gosh—I can’t do this thing I’m supposed to be able to do at this point in my life.’

“I wasn’t necessarily all that competitive as a kid, but for some reason that really bothered me,” says Smith, 50. “I went home and asked my mom if we could get a pull-up bar so I could practice.”

Within two years, more than half of US public schools had enacted the presidential fitness program. The pilot program, involving more than 200,000 students, found that 25 percent of those who had initially failed the challenges were able to pass after six weeks.

But five decades later, despite efforts by other administrations, research shows that children and adults are in worse shape.

“Unfortunately, Americans today are not healthier than we were in the ’60s,” says Shellie Pfohl, executive director of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, & Nutrition. “Youth and adults today are far less active than when Kennedy was in office.”

A host of factors have caused Americans’ health to decline. Walking to school each day has been replaced by bus rides and carpooling; children spend hours watching TV or on the computer instead of playing outside; and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, restaurant meal portions are four times larger today than in the ’50s.

More than 80 percent of adolescents don’t meet the guidelines for physical activity, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. The number of obese kids ages 12 to 19 has more than tripled in the past 30 years. It’s even worse for older generations: Two-thirds of US adults are considered overweight.

While the fitness goals of the ’50s and ’60s were to build up a military fighting force, today’s council has shifted its focus to combatting obesity. The current mission is promoting not just physical activity but overall health. That includes a greater emphasis on nutrition, a topic all but ignored in the ’60s. “In our nation’s history, we have never had the steady, directed focus of the White House on physical activity and healthy eating, nor the spotlight on the obesity epidemic that we have now due to the First Lady’s Let’s Move initiative,” Pfohl says.

McKenzie explains that the council and Let’s Move have increased efforts to ensure that the health campaign reaches all Americans, including underserved populations and those with disabilities. “When the fitness campaigns were happening, Eisenhower and Kennedy really ignored the African-American population,” she says. “People tended to think that those involved in manual labor did not need physical exercise to the same extent as those involved in white-collar jobs. We now know that’s not true.”

In September 2012, the presidential fitness challenges were replaced with a new Presidential Youth Fitness Program, which not only encompasses physical-fitness assessments but also evaluates students’ nutrition and provides professional development. Some of the new assessments measure flexibility and balance—both vital for wellness, particularly later in life. While the flexed-arm hang is still one of the challenges, there’s also a sit-and-reach test to measure flexibility.

“It’s really changed from awarding just the very highest level of excellence to trying to work for everybody,” says Lambdin, whose organization partnered with the council to develop the new program.

She notes that Americans today may not be any healthier than in the ’60s, but at least they’re more aware of the benefits of being fit and eating right: “We know much more about how the body works now than we did then. Everybody needs to know how to take care of themselves for a lifetime.”

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.