There’s no sign to tell you that you’ve arrived at RdV, a small winery and 16-acre vineyard in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Delaplane, Virginia. Ascending a steep rise toward a white barn with cathedral-style windows and a silo, you wonder if you’ve missed your turn and mistakenly trespassed onto private property.

Here’s what else you won’t see: picnics on the lawn on weekends, a gift shop stocked with cheese boards and napa is for auto parts bumper stickers, or weddings on the property. Such accoutrements to attract the casual wine drinker are common throughout Virginia but anathema at RdV, which has styled itself as a purist’s operation. The emphasis is on the wine. Not that it’s easy to get your hands on a bottle. RdV has a tasting room, but it’s closed to visitors. Sampling the two wines, produced in limited quantity, is by appointment only.

The air of secrecy more befits a covert military operation than a winery, but what’s going on at RdV does amount to a grand experiment, one that might well alter the landscape of wine in Virginia–and beyond.

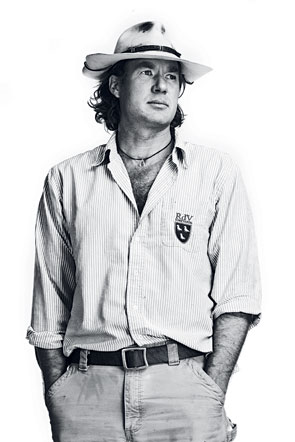

RdV is the vision of a man with the spy-novel name Rutger de Vink, who is bent on proving that the state can produce world-class wines. He speaks with the earnest high-mindedness of a scientist at work on a breakthrough drug and has supreme confidence in his plan, which he has executed with patience and deliberation over the past eight years–prioritizing the vineyard above the cellar, limiting the number of wines he’ll make and the size of the crop he’ll grow each year, engaging the services of the leading viticultural minds of France and California for guidance on everything from the moisture in the soil to the sweetness of the grapes, and refusing to distribute his wines to the public until last spring.

This mania for detail is reflected in the prices. His RdV–a big, soft red–costs two and three times as much as the state’s best wines. He sold the 2008 vintage for $88 a bottle. The 2009 will be bottled as Lost Mountain.

That cost immediately puts wine collectors in mind of Bordeaux, among the most expensive, most sought-after wines in the world. It’s a comparison de Vink encourages. “We respect the terroir of Virginia,” he says, “but we don’t see ourselves so much as a regional player. We want to be a great American wine and a world-class wine.”

De Vink is not a provocateur, but he has emerged as a divisive figure in the world of Virginia wine. Some see him as a potential savior, an ambitious winemaker who may succeed in redeeming the dream of Thomas Jefferson, who struggled in vain to replicate the wines of the noble chateaux of France. Others regard de Vink as a threat, dismayed that the hard-won present may unravel as winemakers indulge, once more, in the 400-year-old dream of copying Europe–and charging accordingly. All are watching closely.

After years of carefully guarded work–de Vink bought the property in 2004–RdV became an overnight sensation last summer when the eminent English critic Jancis Robinson, a guest speaker at a conference of wine bloggers in Charlottesville, tasted RdV’s wines for the first time. In the world of wine, only Robert Parker is better known, and Robinson might be more widely respected for her opinions.

She came away impressed. The wines, she thought, possessed density without heaviness or elevated levels of alcohol. Robinson later posted a gushing profile of RdV on her blog, concluding: “I sincerely believe his considerable efforts stand a good chance of putting the state definitively on the world wine map. . . . I suspect they will have a long and glorious life and, doubtless, raise the bar for other vignerons in the native state of America’s most famously wine-loving president.”

Not since wine made from Daniel Norton’s Virginia Seedling won world acclaim in the 1870s had a Virginia wine been so lauded in the international press. Almost instantly, RdV went from obscurity to the one Virginia winery that oenophiles outside the state want to talk about.

Among the most ardent enthusiasts is Jennifer Knowles, the 37-year-old wine director at the Inn at Little Washington, who added RdV to the restaurant’s vaunted wine list last May. Knowles describes her first taste as a revelation: “I don’t know that I’ve ever been this excited or enthralled about something. It’s like not knowing Bordeaux existed and trying that wine for the first time and going, ‘Whoa–my God.’ “

Not everyone is so captivated, a fact that speaks less to the quality of the wines than to de Vink’s ground-shaking statement of intent.

Winemaking in Virginia has been a 400-year struggle between desire and reality, want and need. It’s a battle marked mostly by failures. The past two decades have been a breakthrough period for Virginia wine, as new technologies and discoveries have led to a change of direction.

The breakthrough has occurred in large part because of the efforts of the so-called “terroir-ists,” a crop of winemakers who contend that fighting nature is fruitless, that the future of wine in the state lies in heeding what the place–the soil, the air, the water–dictates. Some have given up their dreams of making elegant Bordeaux-style blends and Chardonnays and have instead devoted themselves largely to producing vin ordinaire–table wine–from such grapes as Viognier, Norton, Cabernet Franc, and Petit Verdot.

Sitting at a table in his tasting room, his large hands laced behind his head as he slouches back in his chair, the strapping de Vink–a former Marine who did a stint in Somalia–has the slyly confident air of a man who believes he has cracked a code. His ease in a rumpled, open-collared shirt and boots suggests that, all things being equal, he’d rather be out pruning vines.

By all accounts, there’s family money at his disposal–his father, a pharmaceutical-company executive in Europe, moved the family across the pond when de Vink was a teenager–but that isn’t immediately apparent. De Vink lives in an Airstream camper on the edge of the property.

Before he takes me on a tour of his immaculately kept cellar and pours me a flight of his wines going back three years, he shows me the silo that juts up from the property. The silo is empty; it performs no real function at the winery. De Vink has turned it into a piece of pure architecture–a kind of secular cathedral.

“The message,” he says, “is we are an agricultural venture. What matters, first and foremost, is the land. Great wine is made in the vineyard, not the cellar.”

De Vink says the overriding lesson of his apprenticeship with Jim Law of Linden Vineyards, for whom he worked in 2001 and 2002, was the importance of finding the right piece of land. Daniel Roberts–a soil scientist who has helped build vineyards in California, Australia, New Zealand, and Argentina and knew of de Vink’s desire to grow Cabernet Sauvignon–advised him to “find the rockiest, best-drained piece of ground he could find and then call me.”

It took three years of looking–a period that tried de Vink’s patience and tested his resolve as he rejected picture-postcard parcels over and over again. He finally stumbled upon his steeply graded, 100-acre plot in 2004, a mere 13 miles from Law–the perfect mix, he believed, of rocky soil, slope angle, and drainage prospects. Drainage is vitally important in a state that, compared with the meager rainfalls of California and France, is something of a swamp. A vineyard without excellent drainage can produce vegetation during the growing season, severely compromising the ability of the vines to produce good, concentrated fruit.

To the uninitiated, it looked anything but promising. When de Vink began digging, a man in the crew turned to him and shook his head, saying: “I’m sorry, man. It’s nothing but f—ing rocks here.”

The site scientist de Vink had hired to oversee the digging just laughed. “No, no,” he said. “That’s gonna get you a $100 bottle right there.”

Rocky soils are essential to producing wines of depth and length. They arrest the development of the vines and direct all the vegetative energy to the seeds. As if to underscore the importance of rockiness, de Vink has installed giant, test-tube-like samples of the soil outside the cellar. They resemble parfait glasses filled with trifle–but they’re filled with granite.

The 16 acres of vines look stark against their rugged terrain. They’re immaculately pruned, and the wide spacing of the vines is vivid testament to de Vink’s willingness to settle for a low yield.

Few wineries have the money–it takes six vignerons, or vineyard workers, to maintain the vineyard–or the patience to commit to such an approach. De Vink credits Daniel Roberts and Jean-Philippe Roby, a professor at the University of Bordeaux, not only with advising him on planting but also with counseling him to believe that such stringent methods would yield a handsome payoff. De Vink and Roby met in the early 2000s, during de Vink’s extensive travels through Bordeaux tasting the wines of the great chateaux and picking the brains of the region’s best oenological minds.

Eric Boissenot, a consultant for Château Latour, among others, was so impressed by de Vink’s determination and passion for detail, as well as by the quality of wine de Vink managed to produce from three-year-old vines, that he agreed to supervise the first blending of RdV three years ago–weighing in via e-mail on overnighted barrel samples. The process continues today, with deliveries going out every week from Delaplane to Bordeaux. Boissenot also spends weeks at RdV during blending. The idea that a promising bastion for Bordeaux has been unearthed in the New World, he says, is “extraordinarily exciting.”

The terroir-ists have only kind words for de Vink and the seriousness of his approach, and they’re eager to see how the winery evolves. But they’re skeptical of his mission and uneasy about what his success might portend.

Jenni McCloud of Chrysalis Vineyards, who met de Vink more than a decade ago and was “duly impressed,” says she’s watching closely. “Let’s see if the wines stand up. Will those wines age? Will they develop the incredible complexity and character that happen with those wines from Bordeaux?”

Luca Paschina, the winemaker at Barboursville Vineyards, one of Virginia’s oldest and most respected wineries, says there’s a word for what de Vink has inspired. “Envy,” he says with a laugh.

He admires de Vink’s devotion to detail, his willingness to learn, his drive to succeed. Still, he says, “We all know there isn’t that great a difference between a $100 bottle of wine and a $35 bottle.”

A sampling at RdV is a striking departure from the sniff-and-sip experience over a tasting-room counter that most wineries proffer: It’s like going from coach to first class. De Vink wants potential customers to see the wines at work–that is, at the table–believing that experiencing the way they pair with food is essential to understanding what he’s doing.

De Vink pours three vintages of his two wines. Rendezvous, which sold for $55–the 2009 is priced at $75–is a Merlot blend. RdV/Lost Mountain, his signature, is Cabernet-dominant. Wine is not a reductive experience, and no pile of adjectives can capture the complex and elusive magic of a great bottle, as these both are. To say they’re rich but supple, or elegant but earthy, only hints at their power and mystery, not to mention the deep and lingering pleasure they give.

Sommeliers would describe them as “fruit-forward,” as many Napa reds are, filling the mouth with a taste of fresh, ripe berries, among other qualities. But there’s also a note of leanness, an acidity, that the best French wines possess. They’re big, but they dance.

De Vink clearly has proven that it’s possible to make a good Bordeaux-style wine in Virginia. He’s also proven so far that it’s possible only at enormous cost and only as long as you limit growth and accept a low yield.

Can he continue to produce great wines, year in and year out, given the vagaries of the Piedmont weather? Can he add more wines to RdV’s portfolio and prove that the vineyard is more than a glorified vanity project? Is this a template that anyone without de Vink’s mania for detail, deep pockets, and a vast network of connections can pull off, or is it an intriguing one-off?

De Vink has heard all the questions and criticisms, and precious little of it seems to have penetrated. This appears to be partly a function of his extraordinary focus and partly of an easygoing disposition.

Lunch over, he reaches for a glass of RdV, surveying a table covered in plates and stemware, and takes a lingering, reflective sip.

“I love it when people say, ‘This is very nice. It doesn’t taste like a Virginia wine.’ ” He laughs. “Like, what does that mean?”

This article appears in the May 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.